EduTech AU 2015, Day 2, Higher Ed Leaders, “Innovation + Technology = great change to higher education”, #edutechau

Posted: June 3, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, collaboration, community, connectivity, design, education, educational problem, educational research, edutech2015, edutechau, ethics, grand challenge, higher education, learning, market forces, measurement, mit, mit media lab, Nicholas, nicholas negroponte, olpc, one laptop per child, principles of design, public education, resources, seymour papert, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools Leave a commentBig session today. We’re starting with Nicholas Negroponte, founder of the MIT Media Lab and the founder of One Laptop Per Child (OLPC), an initiative to create/provide affordable educational devices for children in the developing world. (Nicholas is coming to us via video conference, hooray, 21st Century, so this may or not work well in translation to blogging. Please bear with me if it’s a little disjointed.)

Nicholas would rather be here but he’s bravely working through his first presentation of this type! It’s going to be a presentation with some radical ideas so he’s hoping for conversation and debate. The presentation is broken into five parts:

- Learning learning. (Teaching and learning as separate entities.)

- What normal market forces will not do. (No real surprise that standard market forces won’t work well here.)

- Education without curricula. (Learning comes from many places and situations. Understanding and establishing credibility.)

- Where do new ideas come from? (How do we get them, how do we not get in the way.)

- Connectivity as a human right. (Is connectivity a human right or a means to rights such as education and healthcare? Human rights are free so that raises a lot of issues.

Nicholas then drilled down in “Learning learning”, starting with a reference to Seymour Papert, and Nicholas reflected on the sadness of the serious accident of Seymour’s health from a personal perspective. Nicholas referred to Papert’s and Minsky’s work on trying to understand how children and machines learned respectively. In 1968, Seymour started thinking about it and on April, 9, 1970, he gave a talk on his thoughts. Seymour realised that thinking about programs gave insight into thinking, relating to the deconstruction and stepwise solution building (algorithmic thinking) that novice programmers, such as children, had to go through.

These points were up on the screen as Nicholas spoke:

- Construction versus instruction

- Why reinventing the wheel is good

- Coding as thinking about thinking

How do we write code? Write it, see if it works, see which behaviours we have that aren’t considered working, change the code (in an informed way, with any luck) and try again. (It’s a little more complicated than that but that’s the core.) We’re now into the area of transferable skills – it appeared that children writing computer programs learned a skill that transferred over into their ability to spell, potentially from the methodical application of debugging techniques.

Nicholas talked about a spelling bee system where you would focus on the 8 out of 10 you got right and ignore the 2 you didn’t get. The ‘debugging’ kids would talk about the ones that they didn’t get right because they were analsysing their mistakes, as a peer group and as individual reflection.

Nicholas then moved on to the failure of market forces. Why does Finland do so well when they don’t have tests, homework and the shortest number of school hours per day and school days per year. One reason? No competition between children. No movement of core resources into the private sector (education as poorly functioning profit machine). Nicholas identified the core difference between the mission and the market, which beautifully summarises my thinking.

The OLPC program started in Cambodia for a variety of reasons, including someone associated with the lab being a friend of the King. OLPC laptops could go into areas where the government wasn’t providing schools for safety reasons, as it needed minesweepers and the like. Nicholas’ son came to Cambodia from Italy to connect up the school to the Internet. What would the normal market not do? Telecoms would come and get cheaper. Power would come and get cheaper. Laptops? Hmm. The software companies were pushing the hardware companies, so they were both caught in a spiral of increasing power consumption for utility. Where was the point where we could build a simple laptop, as a mission of learning, that could have a smaller energy footprint and bring laptops and connectivity to billions of people.

This is one of the reasons why OLPC is a non-profit – you don’t have to sell laptops to support the system, you’re supporting a mission. You didn’t need to sell or push to justify staying in a market, as the production volume was already at a good price. Why did this work well? You can make partnerships that weren’t possible otherwise. It derails the “ah, you need food and shelter first” argument because you can change the “why do we need a laptop” argument to “why do we need education?” at which point education leads to increased societal conditions. Why laptops? Tablets are more consumer-focused than construction-focused. (Certainly true of how I use my tech.)

(When we launched the first of the Digital Technologies MOOCs, the deal we agreed upon with Google was that it wasn’t a profit-making venture at all. It never will be. Neither we nor Google make money from the support of teachers across Australia so we can have all of the same advantages as they mention above: open partnerships, no profit motive, working for the common good as a mission of learning and collegial respect. Highly recommended approach, if someone is paying you enough to make your rent and eat. The secret truth of academia is that they give you money to keep you housed, clothed and fed while you think. )

Nicholas told a story of kids changing from being scared or bored of school to using an approach that brings kids flocking in. A great measure of success.

Now, onto Education without curricula, starting by talking public versus private. This is a sensitive subject for many people. The biggest problem for public education in many cases is the private educational system, dragging out caring educators to a closed system. Remember Finland? There are no public schools and their educational system is astoundingly good. Nicholas’ points were:

- Public versus private

- Age segregation

- Stop testing. (Yay!)

The public sector is losing the imperative of the civic responsibility for education. Nicholas thinks it doesn’t make sense that we still segregate by ages as a hard limit. He thinks we should get away from breaking it into age groups, as it doesn’t clearly reflect where students are at.

Oh, testing. Nicholas correctly labelled the parental complicity in the production of the testing pressure cooker. “You have to get good grades if you’re going to Princeton!” The testing mania is dominating institutions and we do a lot of testing to measure and rank children, rather than determining competency. Oh, so much here. Testing leads to destructive behaviour.

So where do new ideas come from? (A more positive note.) Nicholas is interested in Higher Ed as sources of new ideas. Why does HE exist, especially if we can do things remotely or off campus? What is the role of the Uni in the future? Ha! Apparently, when Nicholas started the MIT media lab, he was accused of starting a sissy lab with artists and soft science… oh dear, that’s about as wrong as someone can get. His use of creatives was seen as soft when, of course, using creative users addressed two issues to drive new ideas: a creative approach to thinking and consulting with the people who used the technology. Who really invented photography? Photographers. Three points from this section.

- Children: our most precious natural resource

- Incrementalism is the enemy of creativity

- Brain drain

On the brain drain, we lose many, many students to other places. Uni are a place to solve huge problems rather than small, profit-oriented problems. The entrepreneurial focus leads to small problem solution, which is sucking a lot of big thinking out of the system. The app model is leading to a human resource deficit because the start-up phenomenon is ripping away some of our best problem solvers.

Finally, to connectivity as a human right. This is something that Nicholas is very, very passionate about. Not content. Not laptops. Being connected. Learning, education, and access to these, from early in life to the end of life – connectivity is the end of isolation. Isolation comes in many forms and can be physical, geographical and social. Here are Nicholas’ points:

- The end of isolation.

- Nationalism is a disease (oh, so much yes.) Nations are the wrong taxonomy for the world.

- Fried eggs and omelettes.

Fried eggs and omelettes? In general, the world had crisp boundaries, yolk versus white. At work/at home. At school/not at school. We are moving to a more blended, less dichotomous approach because we are mixing our lives together. This is both bad (you’re getting work in my homelife) and good (I’m getting learning in my day).

Can we drop kids into a reading environment and hope that they’ll learn to read? Reading is only 3,500 years old, versus our language skills, so it has to be learned. But do we have to do it the way that we did it? Hmm. Interesting questions. This is where the tablets were dropped into illiterate villages without any support. (Does this require a seed autodidact in the group? There’s a lot to unpack it.) Nicholas says he made a huge mistake in naming the village in Ethiopia which has corrupted the experiment but at least the kids are getting to give press conferences!

Another massive amount of interesting information – sadly, no question time!

EduTECH AU 2015, Day 1, Higher Ed Leaders, “Revolutionising the Student Experience: Thinking Boldly” #edutechau

Posted: June 2, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: AI, artificial intelligence, blogging, collaboration, community, data visualisation, deakin, design, education, educational research, edutech2015, edutecha, edutechau, ethics, higher education, learning, learning analytics, machine intelligence, measurement, principles of design, resources, student perspective, students, teaching, thinking, tools, training, watson Leave a commentLucy Schulz, Deakin University, came to speak about initiatives in place at Deakin, including the IBM Watson initiative, which is currently a world-first for a University. How can a University collaborate to achieve success on a project in a short time? (Lucy thinks that this is the more interesting question. It’s not about the tool, it’s how they got there.)

Some brief facts on Deakin: 50,000 students, 11,000 of whom are on-line. Deakin’s question: how can we make the on-line experience as good if not better than the face-to-face and how can on-line make face-to-face better?

Part of Deakin’s Student Experience focus was on delighting the student. I really like this. I made a comment recently that our learning technology design should be “Everything we do is valuable” and I realise now I should have added “and delightful!” The second part of the student strategy is for Deakin to be at the digital frontier, pushing on the leading edge. This includes understanding the drivers of change in the digital sphere: cultural, technological and social.

(An aside: I’m not a big fan of the term disruption. Disruption makes room for something but I’d rather talk about the something than the clearing. Personal bug, feel free to ignore.)

The Deakin Student Journey has a vision to bring students into the centre of Uni thinking, every level and facet – students can be successful and feel supported in everything that they do at Deakin. There is a Deakin personality, an aspirational set of “Brave, Stylish, Accessible, Inspiring and Savvy”.

Not feeling this as much but it’s hard to get a feel for something like this in 30 seconds so moving on.

What do students want in their learning? Easy to find and to use, it works and it’s personalised.

So, on to IBM’s Watson, the machine that won Jeopardy, thus reducing the set of games that humans can win against machines to Thumb Wars and Go. We then saw a video on Watson featuring a lot of keen students who coincidentally had a lot of nice things to say about Deakin and Watson. (Remember, I warned you earlier, I have a bit of a thing about shiny videos but ignore me, I’m a curmudgeon.)

The Watson software is embedded in a student portal that all students can access, which has required a great deal of investigation into how students communicate, structurally and semantically. This forms the questions and guides the answer. I was waiting to see how Watson was being used and it appears to be acting as a student advisor to improve student experience. (Need to look into this more once day is over.)

Ah, yes, it’s on a student home page where they can ask Watson questions about things of importance to students. It doesn’t appear that they are actually programming the underlying system. (I’m a Computer Scientist in a faculty of Engineering, I always want to get my hands metaphorically dirty, or as dirty as you can get with 0s and 1s.) From looking at the demoed screens, one of the shiny student descriptions of Watson as “Siri plus Google” looks very apt.

Oh, it has cheekiness built in. How delightful. (I have a boundless capacity for whimsy and play but an inbuilt resistance to forced humour and mugging, which is regrettably all that the machines are capable of at the moment. I should confess Siri also rubs me the wrong way when it tries to be funny as I have a good memory and the patterns are obvious after a while. I grew up making ELIZA say stupid things – don’t judge me! 🙂 )

Watson has answered 26,000 questions since February, with an 80% accuracy for answers. The most common questions change according to time of semester, which is a nice confirmation of existing data. Watson is still being trained, with two more releases planned for this year and then another project launched around course and career advisors.

What they’ve learned – three things!

- Student voice is essential and you have to understand it.

- Have to take advantage of collaboration and interdependencies with other Deakin initiatives.

- Gained a new perspective on developing and publishing content for students. Short. Clear. Concise.

The challenges of revolution? (Oh, they’re always there.) Trying to prevent students falling through the cracks and make sure that this tool help students feel valued and stay in contact. The introduction of new technologies have to be recognised in terms of what they change and what they improve.

Collaboration and engagement with your University and student community are essential!

Thanks for a great talk, Lucy. Be interesting to see what happens with Watson in the next generations.

EduTECH AU 2015, Day 1, Higher Ed Leaders, Panel Discussion “Leveraging data for strategic advantage” #edutechau

Posted: June 2, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: analytics, blogging, data analytics, education, educational problem, educational research, edutech2015, edutechau, ethics, higher education, learning analytics, measurement, principles of design, reflection, students, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a commentA most distinguished panel today. It can be hard to capture panel discussions so I will do what I can to get the pertinent points down. However, the fact that we are having this panel gives you some indication of the importance of this issue. Getting to know your data will make it easier for you to work out what to do in the future.

University of Wollongong (UoW) have set up a University-wide approach to Learning Analytics, with 30 courses in an early adopter program, scaling up over the next two years. Give things that they have learned.

- You need to have a very clear strategic approach for learning analytics. Learning analytics are built into key strategies. This ties in the key governing bodies and gives you the resources.

- Learning analytics need to be tied into IT and data management strategies – separating infrastructure and academics won’t work.

- The only driver for UoW is the academic driver, not data and not technology. All decisions are academic. “what is the value that this adds to maximums student learning, provide personalised learning and early identification of students at risk?”

- Governance is essential. UoW have a two-tier structure, a strategic group and an ethical use of data group. Both essential but separate.

- With data, and learning analytics, comes a responsibility for action. Actions by whom and, then, what action? What are the roles of the student, staff and support services? Once you have seen a problem that requires intervention, you are obliged to act.

I totally agree with this. I have had similar arguments on the important nature of 5.

The next speaker is from University of Melbourne (UoM), who wanted to discuss a high-level conceptual model. At the top of the model is the term ‘success’, a term that is not really understood or widely used, at national or local level. He introduced the term of ‘education analytics’ where we look at the overall identity of the student and interactions with the institution. We’re not having great conversations with students through written surveys so analytics can provide this information (a controversial approach). UoM want a new way, a decent way, to understand the student, rather than taking a simplistic approach. I think he mentioned intersectionality but not in a way that I really understood it.

Most of what determines student success in Australia isn’t academic, it’s personal, and we have to understand that. We also can’t depend on governments to move this, it will have to come out of the universities.

The next speaker is from University of Sydney, who had four points he wanted to make.

He started by talking about the potential of data. Data is there but it’s time to leverage it. Why are institutions not adopting LA as fast as they could? We understand the important of data-backed decision making.

Working with LA requires a very broad slice across the University – IT, BI, Academics, all could own it and they all want to control it. We want to collaborate so we need clear guidance and clear governance. Need to identify who is doing what without letting any one area steal it.

Over the last years, we have forgotten about the proximity of data. It’s all around us but many people think it’s not accessible. How do we get our hands on all of this data to make information-backed decisions in the right timeframe? This proximity applies to students as well, they should be able to see what’s going on as a day-by-day activity.

The final panellist is from Curtin University. Analytics have to be embedded into daily life and available with little effort if they’re going to be effective. At Curtin, analytics have a role in all places in the Uni, library, learning, life-long learning, you name it. Data has to be unified and available on demand. What do users want?

Curtin focused on creating demand – can they now meet that demand with training and staffing, to move to the next phase of attraction?

Need to be in a position of assisting everyone. This is a new world so have to be ready to help people quite a lot in the earlier stages. Is Higher Ed ready for the type of change that Amazon caused in the book market? Higher Ed can still have a role as validator of education but we have to learn to work with new approaches before our old market is torn out form underneath us.

We need to disentangle what the learner does from what the machine does.

That finished off the initial panel statements and then the chair moved to ask questions to the panel. I’ll try and summarise that.

One question was about the issue of security and privacy of student information. Can we take data that we used to help a student to complete their studies and then use that to try and recruit a new student, even anonymised? UoW mentioned that having a separate data ethics group for exactly this reason. UoW started this with a student survey, one question of which is “do you feel like this is Big Brother”. Fortunately, most felt that it wasn’t but they wanted to know what was going to happen with the data and the underlying driver had to be to help them to succeed.

Issuing a clear policy and embracing transparency is crucial here.

UoM made the point that much work is not built on a strong theoretical basis and a great deal of it is measuring what we already think we care about. There is a lot of value in clearly identifying what works and what doesn’t.

That’s about it for this session. Again, so much to think about.

EduTech Australia 2015, Day 1, Session 2, Higher Education IT Leaders #edutechau

Posted: June 2, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: blogging, community, customer-centric, design, digital technologies, education, educational research, edutech2015, edutechau, higher education, learning technologies, mark gregory, measurement, principles of design, resources, technology services, the university of adelaide, tools, University of Adelaide Leave a commentI jumped streams (GASP) to attend Mark Gregory’s talk on “Building customer-centric IT services.” Mark is the CIO from my home institutions, the University of Adelaide, and I work closely with him on a couple of projects. There’s an old saying that if you really want to know what’s going on in your IT branch, go and watch the CIO give a presentation away from home, which may also explain why I’m here. (Yes, I’m a dreadful cynic.)

Seven years ago, we had the worst customer-centric IT ratings in Australia and New Zealand, now we have some of the highest. That’s pretty impressive and, for what it’s worth, it reflects my experiences inside the institution.

Mark showed a picture of the ENIAC team, noting that the picture had been mocked up a bit, as additional men had been staged in the picture, which was a bit strange even the ENIAC team were six women to one man. (Yes, this has been going on for a long time.) His point was that we’ve come a long way from he computer attended by acolytes as a central resource to computers everywhere that everyone can access and we have specifically chosen. Technology is now something that you choose rather than what you put up with.

For Adelaide, on a typical day we see about 56,000 devices on the campus networks, only a quarter of which are University-provided. Over time, the customer requirement for centralised skills is shrinking as their own skills and the availability of outside (often cloud-based) resources increase. In 2020-2025, fewer and fewer of people on campus will need centralised IT.

Is ERP important? Mark thinks ‘Meh’ because it’s being skinned with Apps and websites, the actual ERP running in the background. What about networks? Well, everyone’s got them. What about security? That’s more of an imposition and it’s used by design issues. Security requirements are not a crowd pleaser.

So how will our IT services change over time?

A lot of us are moving from SOE to BYOD but this means saying farewell to the Standard Operating Environment (SOE). It’s really not desirable to be in this role, but it also drives a new financial model. We see 56,000 devices for 25,000 people – the mobility ship has sailed. How will we deal with it?

We’re moving from a portal model to an app model. The one stop shop is going and the new model is the build-it-yourself app store model where every device is effectively customised. The new user will not hang out in the portal environment.

Mark thinks we really, really need to increase the level of Self Help. A year ago, he put up 16 pages of PDFs and discovered that, over the year, 35,000 people went through self help compared to 70,000 on traditional help-desk. (I question that the average person in the street knows that an IP address given most of what I see in movies. 😉 )

The newer operating systems require less help but student self-help use is outnumbered 5 times by staff usage. Students go somewhere else to get help. Interesting. Our approaches to VPN have to change – it’s not like your bank requires one. Our approaches to support have to change – students and staff work 24×7, so why were we only supporting them 8-6? Adelaide now has a contract service outside of those hours to take the 100 important calls that would have been terrible had they not been fixed.

Mark thinks that IDM and access need to be fixed, it makes up 24% of their reported problems: password broken, I can’t get on and so on.

Security used to be on the device that the Uni owned. This has changed. Now it has to be data security, as you can’t guarantee that you own the device. Virtual desktops and virtual apps can offer data containerisation among their other benefits.

Let’s change the thinking from setting a perimeter to the person themselves. The boundaries are shifting and, let’s be honest, the inside of any network with 30,000 people is going to be swampy anyway.

Project management thinking is shifting from traditional to agile, which gets closer to the customer on shorter and smaller projects. But you have to change how you think about projects.

A lot of tools used to get built that worked with data but now people want to make this part of their decision infrastructure. Data quality is now very important.

The massive shift is from “provide and control” to “advise and enable”. (Sorry, auditors.) Another massive shift is from automation of a process that existed to support a business to help in designing the processes that will support the business. This is a driver back into policy space. (Sorry, central admin branch.) At the same time, Mark believes that they’re transitioning from a functional approach to a customer-centric focus. A common services layer will serve the student, L&T, research and admin groups but those common services may not be developed or even hosted inside the institution.

It’s not a surprise to anyone who’s been following what Mark has been doing, but he believes that the role is shifting from IT operations to University strategy.

Some customers are going to struggle. Some people will always need help. But what about those highly capable individuals who could help you? This is where innovation and co-creation can take place, with specific people across the University.

Mark wants Uni IT organisations to disrupt themselves. (The Go8 are rather conservative and are not prone to discussing disruption, let alone disrupting.)

Basically, if customers can do it, make themselves happy and get what they want working, why are you in their way? If they can do it themselves, then get out of the way except for those things where you add value and make the experience better. We’re helping people who are desperate but we’re not putting as much effort into the innovators and more radical thinkers. Mark’s belief is that investing more effort into collaboration, co-creation and innovation is the way to go.

It looks risky but is it? What happens if you put technology out there? How do you get things happening?

Mark wants us to move beyond Service Level Agreements, which he describes as the bottom bar. No great athlete performs at the top level because of an SLA. This requires a move to meaningful metrics. (Very similar to student assessment, of course! Same problem!) Just because we measure something doesn’t make it meaningful!

We tended to hire skills to provide IT support. Mark believes that we should now be hiring attributes: leaders, drivers, innovators. The customer wants to get somewhere. How can we help them?

Lots to think about – thanks, Mark!

EduTech Australia 2015, Day 1, Session 1, Part 2, Higher Ed Leaders #edutechau

Posted: June 2, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: community, curriculum, design, Diane Oblinger, differentiator, education, educational problem, educational research, edutech2015, edutechau, ethics, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, resources, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentThe next talk was a video conference presentation, “Designed to Engage”, from Dr Diane Oblinger, formerly of EDUCAUSE (USA). Diane was joining us by video on the first day of retirement – that’s keen!

Today, technology is not enough, it’s about engagement. Diane believes that the student experience can be a critical differentiator in this. In many institutions, the student will be the differentiator. She asked us to consider three different things:

- What would life be like without technology? How does this change our experiences and expectations?

- Does it have to be human-or-machine? We often construct a false dichotomy of online versus face-to-face rather than thinking about them as a continuum.

- Changes in demography are causing new consumption patterns.

Consider changes in the four key areas:

- Learning

- Pathways

- Credentialing

- Alternate Models

To speak to learning, Diane wants us to think about learning for now, rather than based on our own experiences. What will happen when classic college meets online?

Diane started from the premise that higher order learning comes from complex challenges – how can we offer this to students? Well, there are game-based, high experiential activities. They’re complex, interactive, integrative, information gathering driven, team focused and failure is part of the process. They also develop tenacity (with enough scaffolding, of course). We also get, almost for free, vast quantities of data to track how students performed their solving activities, which is far more than “right” or “wrong”. Does a complex world need more of these?

The second point for learning environments is that, sometimes, massive and intensive can go hand-in-hand. The Georgia Tech Online Master of Science in Computer Science, on Udacity , with assignments, TAs and social media engagements and problem-solving. (I need to find out more about this. Paging the usual suspects.)

The second area discussed was pathways. Students lose time, track and credits when they start to make mistakes along the way and this can lead to them getting lost in the system. Cost is a huge issue in the US (and, yes, it’s a growing issue in Australia, hooray.) Can you reduce cost without reducing learning? Students are benefiting from guided pathways to success. Georgia State and their predictive analytics were mentioned again here – leading students to more successful pathways to get better outcomes for everyone. Greatly increased retention, greatly reduced wasted tuition fees.

We now have a lot more data on what students are doing – the challenge for us is how we integrate this into better decision making. (Ethics, accuracy, privacy are all things that we have to consider.)

Learning needs to not be structured around seat time and credit hours. (I feel dirty even typing that.) Our students learn how to succeed in the environments that we give them. We don’t want to train them into mindless repetition. Once again, competency based learning, strongly formative, reflecting actual knowledge, is the way to go here.

(I really wish that we’d properly investigated the CBL first year. We might have done something visionary. Now we’ll just look derivative if we do it three years from now. Oh, well, time to start my own University – Nickapedia, anyone?)

Credentials raised their ugly head again – it’s one of the things that Unis have had in the bag. What is the new approach to credentials in the digital environment? Certificates and diplomas can be integrated into your on-line identity. (Again, security, privacy, ethics are all issues here but the idea is sound.) Example given was “Degreed”, a standalone credentialing site that can work to bridge recognised credentials from provide to employer.

Alternatives to degrees are being co-created by educators and employers. (I’m not 100% sure I agree with this. I think that some employers have great intentions but, very frequently, it turns into a requirement for highly specific training that might not be what we want to provide.)

Can we reinvent an alternative model that reinvents delivery systems, business models and support models? Can a curriculum be decentralised in a centralised University? What about models like Minerva? (Jeff mentioned this as well.)

(The slides got out of whack with the speaker for a while, apologies if I missed anything.)

(I should note that I get twitchy when people set up education for-profit. We’ve seen that this is a volatile market and we have the tension over where money goes. I have the luxury of working for an entity where its money goes to itself, somehow. There are no shareholders to deal with, beyond the 24,000,000 members of the population, who derive societal and economic benefit from our contribution.)

As noted on the next slide, working learners represent a sizeable opportunity for increased economic growth and mobility. More people in college is actually a good thing. (As an aside, it always astounds me when someone suggests that people are spending too much time in education. It’s like the insult “too clever by half”, you really have to think about what you’re advocating.)

For her closing thoughts, Diane thinks:

- The boundaries of the educational system must be re-conceptualised. We can’t ignore what’s going on around us.

- The integration of digital and physical experiences are creating new ways to engage. Digital is here and it’s not going away. (Unless we totally destroy ourselves, of course, but that’s a larger problem.)

- Can we design a better future for education.

Lots to think about and, despite some technical issues, a great talk.

EduTech Australia 2015, Day 1, Session 1, Higher Education Leaders @jselingo #edutechau

Posted: June 2, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, blogging, education, educational research, edutech2015, edutechau, higher education, Jeffrey Selingo, learning, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, workload Leave a commentEmeritus Professor Steven Schwartz, AM, opened the Higher Ed leaders session, following a very punchy video on how digital is doing “zoom” and “rock and roll” things. (I’m a bit jaded about “tech wow” videos but this one was pretty good. It reinforced the fact that over 60% of all web browsing is carried out on mobile devices, which should be a nudge to all of us designing for the web.)

There will be roughly 5,000 participants in the totally monstrous Brisbane Convention Centre. There are many people here that I know but I’m beginning to doubt whether I’m going to see many of them unless they’re speaking – there’s a mass of educational humanity here, people!

The opening talk was “The Universities of tomorrow, the future of anytime and anywhere learning”, presented by Jeffrey Selingo. Jeff writes books, “College Unbound” among others, and is regular contributor to the Washington Post and the Chronicle. (I live for the day I can put “Education Visionary” on my slides with even a shred of this credibility. As a note, remarks in parentheses are probably my editorial comments.)

(I’ve linked to Jeff on Twitter. Please correct me on anything, Jeff!)

Jeff sought out to explore the future of higher learning, taking time out from editing the Chronicle. He wanted to tell the story of higher ed for the coming decade, for those parents and students heading towards it now, rather than being in it now. Jeff approached it as a report, rather than an academic paper, and is very open about the fact that he’s not conducting research. “In journalism, if you have three anecdotes, you have a trend.”

(I’m tempted to claim phenomenography but I know you’ll howl me down. And rightly so!)

Higher Ed is something that, now, you encounter once in our lives and then move on. But the growth in knowledge and ongoing explosion of new information doesn’t match that model. Our Higher Ed model is based on an older tradition and and older informational model.

(This is great news for me, I’m a strong advocate of an integrated and lifelong Higher Ed experience)

(Slides for this talk available at http://jeffselingo.com/conference

Be warned, you have to sign up for a newsletter to get the slides.)

Jeff then talked about his start, in one of the initial US college rankings, before we all ranked each other into the ground. The ‘prestige race’ as he refers to it. Every university around the world wanted to move up the ladder. (Except for the ones on the top, kicking at the rungs below, no doubt.)

“Prestige is to higher education as profit is to corporations.”

According to Caroline Hoxby, Higher Ed student flow has increased as students move around the world. Students who can move to different Universities, now tend to do so and they can exercise choices around the world. This leads to predictions like “the bottom 25% of Unis will go out of business or merge” (Clay Christensen) – Jeff disagrees with this although he thinks change is inevitable.

We have a model of new, technologically innovative and agile companies destroy the old leaders. Netflix ate Blockbuster. Amazon ate Borders. Apple ate… well, everybody… but let’s say Tower Records, shall we? Jeff noted that journalism’s upheaval has been phenomenal, despite the view of journalism as a ‘public trust’. People didn’t want to believe what was going to happen to their industry.

Jeff believes that students are going to drive the change. He believes that students are often labelled as “Traditional” (ex-school, 18-22, direct entry) and “non-Traditional” (adult learners, didn’t enter directly.) But what this doesn’t capture is the mindset or motivation of students to go to college. (MOOC motivation issues, anyone?)

What do students want to get out of their degree?

(Don’t ask difficult questions like that, Jeff! It is, of course, a great question and one we try to ask but I’m not sure we always listen.)

Why are you going? What do you want? What do you want your degree to look like? Jeff asked and got six ‘buckets’ of students in two groups, split across the trad/non-trad age groups.

Group 1 are the younger group and they break down into.

- Young Academics (24%) – the trad high-performing students who have mastered the earlier education systems and usually have a privileged background

- Coming of Age (11%) – Don’t quite know what they want from Uni but they were going to college because it was the place to go to become an adult. This is getting them ready to go to the next step, the work force.

- Career Starters (18%) – Students who see the Uni as a means to the end, credentialing for the job that they want. Get through Uni as quickly as possible.

Group 2 are older:

- Career Accelerators (21%) – Older students who are looking to get new credentials to advance themselves in their current field.

- Industry Switchers – Credential changers to move to a new industry.

- Adult Wanderers – needed a degree because that was what the market told them but they weren’t sure why

(Apologies for losing some of the stats, the room’s quite full and some people had to walk past me.)

But that’s what students are doing – what skills are required out there from the employers?

- Written and Oral communication

- Managing multiple priorities

- Collaboration

- Problem solving

People used to go to college for a broad knowledge base and then have that honed by an employer or graduate school to focus them into a discipline. Now, both of these are expected at the Undergrad level, which is fascinating given that we don’t have extra years to add to the degree. But we’re not preparing students better to enter college, nor do we have the space for experiential learning.

Expectations are greater than ever but are we delivering?

When do we need higher education? Well, it used to be “education” then “employment” then “retirement”. The new model, today, (from Georgetown, Tony Carnevale), we have “education”, then “learning and earning”, then “full-time work and on-the-job training”, “transition to retirement” and, finally, “full retirement”. Students are finally focusing on their career at around 30, after leaving the previous learning phases. This is, Jeff believes, where we are not playing an important role for students in their 20s, which is not helping them in their failure to launch.

Jeff was wondering how different life would be for the future, especially given how much longer we are going to be living. How does that Uni experience of “once in our lives, in one physical place” fit in, if people may switch jobs much more frequently over a longer life? The average person apparently switches jobs every four years – no wonder most of the software systems I use are so bad!

Je”s “College Unbound” future is student-driven, student-centred, and not a box that is entered at 18 and existed 4 years later, it’s a platform for life-long learning.

“The illiterate will be those who cannot learn, unlearn and relearn” – Alvin Toffler

Jeff doesn’t think that there will be one simple path to the future. Our single playing field competition of institutions has made us highly similar in the higher ed sector. How can we personalise pathways to the different groups of students that we saw above? Predictive analytics are important here – technology is vital. Good future education will be adaptive and experiential, combining the trad classroom with online systems. apprenticeships and, overall, removing the requirement to reside at or near your college.

Jeff talked about some new models, starting with the Swirl, the unbundled degree across different institutions, traditional snd not. Multiple universities, multiple experiences = degree.

Then there’s mixing course types, mixing face-to-face with hybrid and online to accelerate their speed of graduation. (There is a strong philosophical point on this that I hope to get back to later: why are we racing through University?)

Finally, competency-based learning allowed a learner to have class lengths from 2 weeks to 14 weeks, based on what she already knew. (I am a really serious advocate of this approach. I advocated to switch our entire first year for Engineering to a competency based approach but I’ll write more about that later on. And, no, we didn’t do it but at least we thought about it.)

In the mix are smaller chunks of information and just-in-time learning. Anyone who has used YouTube for a Photoshop tutorial has had a positive (well, as positive as it can be) experience with this. Why can’t we do this with any number of higher ed courses?

A note on the Stanford 2025 Design School exercise: the open loop education. Accepted to Stanford would give you access to 6 years of education that you would be able to use at any point in your life. Take two years, go out and work a bit, come back. Why isn’t the University at the centre of our lifelong involvement with learning?

The distance between producer and consumer is shrinking, whether it’s online stores or 3-D printing. Example given was MarginalRevolutionUniversity, a homegrown University, developed by a former George Mason academic.

As aways, the MOOC dropout rate was raised. Yes, only 10% complete, but Jeff’s interviews confirm what we already know, most of those students had no intention of completing. They didn’t think of the MOOC course as a course or as part of a degree, they were dipping in to get what they needed, when they needed it. Just like those YouTube Photoshop tutorials.

The difficult question is how certify this. And… here are badges again, part of certification of learning and the challenge is how we use them.

Jeff think that there are still benefits for residential experience, although assisted and augmented with technology:

- Faculty mentoring

- Undergraduate research (team work, open problems)

- Be creative. Take Risks. Learn how to fail.

- Cross-cultural experience.

Of course, not all of this is available to everyone. And what is the return on investment for this? LinkedIn finally has enough data that we can start to answer that question. (People will tell LinkedIn things that they won’t tell other people, apparently.) This may change the ranking game because rankings can now be conducted on outputs rather than inputs. Watch this space?

The world is changing. What does Jeff think? Ranking is going to change and we need to be able to prove our value. We have to move beyond isolated disciplines. Skill certification is going to get harder but the overall result should be better. University is for life, not just for three years. This will require us to build deep academic alliances that go beyond our traditional boxes.

Ok, prepping for the next talk!

The driverless car is more than transportation technology.

Posted: May 4, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: AI, blogging, community, data visualisation, driverless car, driverless cars, education, educational problem, Elon Musk, higher education, in the student's head, measurement, principles of design, robots, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, universal principles of design 1 CommentI’m hoping to write a few pieces on design in the coming days. I’ll warn you now that one of them will be about toilets, so … urm … prepare yourself, I guess? Anyway, back to today’s theme: the driverless car. I wanted to talk about it because it’s a great example of what technology could do, not in terms of just doing something useful but in terms of changing how we think. I’m going to look at some of the changes that might happen. No doubt many of you will have ideas and some of you will disagree so I’ll wait to see what shows up in the comments.

Humans have been around for quite a long time but, surprisingly given how prominent they are in our lives, cars have only been around for 120 years in the form that we know them – gasoline/diesel engines, suspension and smaller-than-buggy wheels. And yet our lives are, in many ways, built around them. Our cities bend and stretch in strange ways to accommodate roads, tunnels, overpasses and underpasses. Ask anyone who has driven through Atlanta, Georgia, where an Interstate of near-infinite width can be found running from Peachtree & Peachtree to Peachtree, Peachtree, Peachtree and beyond!

But what do we think of when we think of cars? We think of transportation. We think of going where we want, when we want. We think of using technology to compress travel time and this, for me, is a classic human technological perspective because we are love to amplify. Cars make us faster. Computers allow us to add up faster. Guns help us to kill better.

So let’s say we get driverless cars and, over time, the majority of cars on the road are driverless. What does this mean? Well, if you look at road safety stats and the WHO reports, you’ll see that about up 40% of traffic fatalities can be straight line accidents (these figures from the Victorian roads department, 2006-2013). That is, people just drive off a straight road and kill themselves. The leading killers overall are alcohol, fatigue, and speed. Driverless cars will, in one go, remove all of these. Worldwide, a million people per year just stopped dying.

But it’s not just transportation. In America, commuting to work eats up from 35-65 hours of your year. If you live in DC, you spend two weeks every year cursing the Beltway. And it’s not as if you can easily work in your car so those are lost hours. That’s not enjoyable driving! That’s hours of frustration, wasted fuel, exposure to burning fuel, extra hours you have to work. The fantasy of the car is driving a convertible down the Interstate in the sunshine, listening to rock, and singing along. The reality is inching forward with the windows up in a 10 year old Nissan family car while stuck between FM stations and having to listen to your second iPod because the first one’s out of power. And it’s the joke one that only has Weird Al on it.

Enter the driverless car. Now you can do some work but there’s no way that your commute will be as bad anyway because we can start to do away with traffic lights and keep the traffic moving. You’ll be there for less time but you can do more. Have a sleep if you want. Learn a language. Do a MOOC! Winning!

Why do I think it will be faster? Every traffic light has a period during which no-one is moving. Why? Because humans need clear signals and need to know what other drivers are doing. A driverless car can talk to other cars and they can weave in and out of the traffic signals. Many traffic jams are caused by people hitting the brakes and then people arrive at this braking point faster than people are leaving. There is no need for this traffic jam and, with driverless cars, keeping distance and speed under control is far easier. Right now, cars move like ice through a vending machine. We want them to move like water.

How will you work in your car? Why not make every driverless car a wireless access point using mesh networking? Now the more cars you get together, the faster you can all work. The I495 Beltway suddenly becomes a hub of activity rather than a nightmare of frustration. (In a perfect world, aliens come to Earth and take away I495 as their new emperor, leaving us with matter transporters, but I digress.)

But let’s go further. Driverless cars can have package drops in them. The car that picks you up from work has your Amazon parcels in the back. It takes meals to people who can’t get out. It moves books around.

But let’s go further. Make them electric and put some of Elon’s amazing power cells into them and suddenly we have a power transportation system if we can manage the rapid charge/discharge issues. Your car parks in the city turn into repair and recharge facilities for fleets of driverless cars, charging from the roof solar and wind, but if there’s a power problem, you can send 1000 cars to plug into the local grid and provide emergency power.

We still need to work out some key issues of integration: cyclists, existing non-converted cars and pedestrians are the first ones that come to mind. But, in my research group, we have already developed passive localisation that works on a scale that could easily be put onto cars so you know when someone is among the cars. Combine that with existing sensors and all a cyclist has to do is to wear a sensor (non-personalised, general scale and anonymised) that lets intersections know that she is approaching and the cars can accommodate it. Pedestrians are slow enough that cars can move around them. We know that they can because slow humans do it often enough!

We start from ‘what could we do if we produced a driverless car’ and suddenly we have free time, increased efficiency and the capacity to do many amazing things.

Now, there are going to be protests. There are going to be people demanding their right to drive on the road and who will claim that driverless cars are dangerous. There will be anti-robot protests. There already have been. I expect that the more … freedom-loving states will blow up a few of these cars to make a point. Anyone remember the guy waving a red flag who had to precede every automobile? It’s happened before. It will happen again.

We have to accept that there are going to be deaths related to this technology, even if we plan really hard for it not to happen, and it may be because of the technology or it may be because of opposing human action. But cars are already killing so may people. 1.2 million people died on the road in 2010, 36,000 from America. We have to be ready for the fact that driverless cars are a stepping stone to getting people out of the grind of the commute and making much better use of our cities and road spaces. Once we go driverless we need to look at how many road accidents aren’t happening, and address the issues that still cause accidents in a driverless example.

Understand the problem. Measure what’s happening. Make a change. Measure again. Determine the impact.

When we think about keeping the manually driven cars on the road, we do have a precedent. If you look at air traffic, the NTSB Accidents and Accident Rates by NTSB Classification 1998-2007 report tells us that the most dangerous type of flying is small private planes, which are more than 5 times more likely to have an accident than commercial airliners. Maybe it will be the insurance rates or the training required that will reduce the private fleet? Maybe they’ll have overrides. We have to think about this.

It would be tempting to say “why still have cars” were it not for the increasingly ageing community, those people who have several children and those people who have restricted mobility, because they can’t just necessarily hop on a bike or walk. As someone who has had multiple knee surgeries, I can assure you that 100m is an insurmountable distance sometimes – and I used to run 45km up and down mountains. But what we can do is to design cities that work for people and accommodate the new driverless cars, which we can use in a much quieter, efficient and controlled manner.

Vehicles and people can work together. The Denver area, Bahnhofstrasse in Zurich and Bourke Street Mall in Melbourne are three simple examples where electric trams move through busy pedestrian areas. Driverless cars work like trams – or they can. Predictable, zoned and controlled. Better still, for cyclists, driverless cars can accommodate sharing the road much more easily although, as noted, there may still be some issues for traffic control that will need to be ironed out.

It’s easy to look at the driverless car as just a car but this is missing all of the other things we could be doing. This is just one example where the replacement of something ubiquitous that might just change the world for the better.

What to support? Thoughts on funding for ideas. We must fund the forges of creativity as well as the engines of science (@JulianBurnside #ideasforaus)

Posted: May 3, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, biological science, community, education, educational research, ethics, higher education, Julian Burnside AO QC, Mr Burnside, Opera House, principles of design, reflection, resources Leave a commentThe barrister and #HumanRightsExtremist, Julian Burnside AO QC, was part of today’s Carnegie Conversations at the Opera House. While I’m not there, I was intrigued by a tweet he sent about other discussions going on today regarding the investment of our resources to do the maximum good. (I believe that this was the session following his, with Peter Singer and chaired by Ann Cherry.)

Mr Burnside’s Tweet was (for those who haven’t seen the image):

What to support? Effective Altruism is good, but what about funding the arts, ideas and other things which can’t be measured? #ideasforaus

Some of the responses to this Tweet tried to directly measure the benefits of a cure for Malaria against funding the arts and, to me, this misses the point. I am a scientist, an artist, a husband, a cat steward, and many other things. As a scientist, I use the scientific method when I am undertaking my research into improving education for students and developing better solutions for use of technology. If you were to ask me which is better, putting funds into distributing a malarial cure or subsiding an opera, then we are so close to the endpoint of the activity that the net benefit can be measured. But if you were to ask me whether this means we could defund the arts to concentrate on biological science, I’d have to say no, because the creative development of solutions is not strictly linked to the methodical application of science.

As a computer scientist, I work in vast artificial universes where it is impossible to explore every option because we do not have enough universe. I depend upon insights and creativity to help me work out the solutions, which I can then test methodically. This is a known problem in all forms of large-scale optimisation – we have to settle for finding what we can, seeking the best, and we often have to step away to make sure that the peak we have ascended is not a foothill in the shadow of a greater mountain.

Measuring what goes into the production of a new idea is impossible. I can tell you that a number of my best solutions have come from weeks or months of thinking, combined with music, visits to art galleries, working with my hands, the pattern of water in the shower and the smell of fresh bread.

Once we have an idea then, yes, absolutely, let us fund centres and institutions that support and encourage the most rigorous and excellent mechanisms for turning ideas into reality. When we have a cure for malaria, we must fund it and distribute it, working on ways to reduce delays and cost mark-ups to those who need it most. But we work in spaces so big that walking the whole area is impossible. We depend upon leaps of intuition, creative exploration of solution spaces and, on occasion, flashes of madness to find the ideas that we can then develop

To think that we can focus only on the measurable outcomes is to totally miss the fact that we have no real idea where many of our best ideas come from and yet so many of us have stories of insight and clarity that stem from our interactions with a rich, developed culture of creativity. And that means funding the arts, the ideas and things that we cannot measure.

(Edited to make the hashtag at the top less likely to be misparsed.)

Think. Create. Code. Vis! (@edXOnline, @UniofAdelaide, @cserAdelaide, @code101x, #code101x)

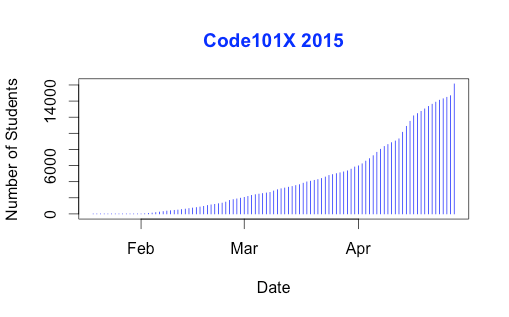

Posted: April 30, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: #code101x, advocacy, blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, data visualisation, education, educational problem, educational research, edx, higher education, learning, measurement, MOOC, moocs, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design Leave a commentI just posted about the massive growth in our new on-line introductory programming course but let’s look at the numbers so we can work out what’s going on and, maybe, what led to that level of success. (Spoilers: central support from EdX helped a huge amount.) So let’s get to the data!

I love visualised data so let’s look at the growth in enrolments over time – this is really simple graphical stuff as we’re spending time getting ready for the course at the moment! We’ve had great support from the EdX team through mail-outs and Twitter and you can see these in the ‘jumps’ in the data that occurred at the beginning, halfway through April and again at the end. Or can you?

Hmm, this is a large number, so it’s not all that easy to see the detail at the end. Let’s zoom in and change the layout of the data over to steps so we can things more easily. (It’s worth noting that I’m using the free R statistical package to do all of this. I can change one line in my R program and regenerate all of my graphs and check my analysis. When you can program, you can really save time on things like this by using tools like R.)

Now you can see where that increase started and then the big jump around the time that e-mail advertising started, circled. That large spike at the end is around 1500 students, which means that we jumped 10% in a day.

When we started looking at this data, we wanted to get a feeling for how many students we might get. This is another common use of analysis – trying to work out what is going to happen based on what has already happened.

As a quick overview, we tried to predict the future based on three different assumptions:

- that the growth from day to day would be roughly the same, which is assuming linear growth.

- that the growth would increase more quickly, with the amount of increase doubling every day (this isn’t the same as the total number of students doubling every day).

- that the growth would increase even more quickly than that, although not as quickly as if the number of students were doubling every day.

If Assumption 1 was correct, then we would expect the graph to look like a straight line, rising diagonally. It’s not. (As it is, this model predicted that we would only get 11,780 students. We crossed that line about 2 weeks ago.

So we know that our model must take into account the faster growth, but those leaps in the data are changes that caused by things outside of our control – EdX sending out a mail message appears to cause a jump that’s roughly 800-1,600 students, and it persists for a couple of days.

Let’s look at what the models predicted. Assumption 2 predicted a final student number around 15,680. Uhh. No. Assumption 3 predicted a final student number around 17,000, with an upper bound of 17,730.

Hmm. Interesting. We’ve just hit 17,571 so it looks like all of our measures need to take into account the “EdX” boost. But, as estimates go, Assumption 3 gave us a workable ballpark and we’ll probably use it again for the next time that we do this.

Now let’s look at demographic data. We now we have 171-172 countries (it varies a little) but how are we going for participation across gender, age and degree status? Giving this information to EdX is totally voluntary but, as long as we take that into account, we make some interesting discoveries.

Our median student age is 25, with roughly 40% under 25 and roughly 40% from 26 to 40. That means roughly 20% are 41 or over. (It’s not surprising that the graph sits to one side like that. If the left tail was the same size as the right tail, we’d be dealing with people who were -50.)

The gender data is a bit harder to display because we have four categories: male, female, other and not saying. In terms of female representation, we have 34% of students who have defined their gender as female. If we look at the declared male numbers, we see that 58% of students have declared themselves to be male. Taking into account all categories, this means that our female participant percentage could be as high as 40% but is at least 34%. That’s much higher than usual participation rates in face-to-face Computer Science and is really good news in terms of getting programming knowledge out there.

We’re currently analysing our growth by all of these groupings to work out which approach is the best for which group. Do people prefer Twitter, mail-out, community linkage or what when it comes to getting them into the course.

Anyway, lots more to think about and many more posts to come. But we’re on and going. Come and join us!

Think. Create. Code. Wow! (@edXOnline, @UniofAdelaide, @cserAdelaide, @code101x, #code101x)

Posted: April 30, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: #code101x, advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, cser digital technologies, curriculum, digital technologies, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, higher education, Hugh Davis, learning, MOOC, moocs, on-line learning, research, Southampton, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, University of Southampton 1 CommentThings are really exciting here because, after the success of our F-6 on-line course to support teachers for digital technologies, the Computer Science Education Research group are launching their first massive open on-line course (MOOC) through AdelaideX, the partnership between the University of Adelaide and EdX. (We’re also about to launch our new 7-8 course for teachers – watch this space!)

Our EdX course is called “Think. Create. Code.” and it’s open right now for Week 0, although the first week of real content doesn’t go live until the 30th. If you’re not already connected with us, you can also follow us on Facebook (code101x) or Twitter (@code101x), or search for the hashtag #code101x. (Yes, we like to be consistent.)

I am slightly stunned to report that, less than 24 hours before the first content starts to roll out, that we have 17,531 students enrolled, across 172 countries. Not only that, but when we look at gender breakdown, we have somewhere between 34-42% women (not everyone chooses to declare a gender). For an area that struggles with female participation, this is great news.

I’ll save the visualisation data for another post, so let’s quickly talk about the MOOC itself. We’re taking a 6 week approach, where students focus on developing artwork and animation using the Processing language, but it requires no prior knowledge and runs inside a browser. The interface that has been developed by the local Adelaide team (thank you for all of your hard work!) is outstanding and it’s really easy to make things happen.

I love this! One of the biggest obstacles to coding is having to wait until you see what happens and this can lead to frustration and bad habits. In Processing you can have a circle on the screen in a matter of seconds and you can start playing with colour in the next second. There’s a lot going on behind the screen to make it this easy but the student doesn’t need to know it and can get down to learning. Excellent!

I went to a great talk at CSEDU last year, presented by Hugh Davis from Southampton, where Hugh raised some great issues about how MOOCs compared to traditional approaches. I’m pleased to say that our demography is far more widespread than what was reported there. Although the US dominates, we have large representations from India, Asia, Europe and South America, with a lot of interest from Africa. We do have a lot of students with prior degrees but we also have a lot of students who are at school or who aren’t at University yet. It looks like the demography of our programming course is much closer to the democratic promise of free on-line education but we’ll have to see how that all translates into participation and future study.

While this is an amazing start, the whole team is thinking of this as part of a project that will be going on for years, if not decades.

When it came to our teaching approach, we spent a lot of time talking (and learning from other people and our previous attempts) about the pedagogy of this course: what was our methodology going to be, how would we implement this and how would we make it the best fit for this approach? Hugh raised questions about the requirement for pedagogical innovation and we think we’ve addressed this here through careful customisation and construction (we are working within a well-defined platform so that has a great deal of influence and assistance).

We’ve already got support roles allocated to staff and students will see us on the course, in the forums, and helping out. One of the reasons that we tried to look into the future for student numbers was to work out how we would support students at this scale!

One of our most important things to remember is that completion may not mean anything in the on-line format. Someone comes on and gets an answer to the most pressing question that is holding them back from coding, but in the first week? That’s great. That’s success! How we measure that, and turn that into traditional numbers that match what we do in face-to-face, is going to be something we deal with as we get more information.

The whole team is raring to go and the launch point is so close. We’re looking forward to working with thousands of students, all over the world, for the next six weeks.

Sound interesting? Come and join us!