Not just videos!

Posted: January 14, 2016 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, aesthetics, education, educational research, higher education, moocs, on-line learning, principles of design, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, video Leave a comment

Just a quick note that on-line learning is not just videos! I am a very strong advocate of active learning in my face-to-face practice and am working to compose on-line systems that will be as close to this as possible: learning and doing and building and thinking are all essential parts of the process.

Please, once again, check out Mark’s CACM blog on the 10 myths of teaching computer science. There’s great stuff here that extends everything I’m talking about with short video sequences and attention spans. I wrote something ages ago about not turning ‘chalk and talk’ into ‘watch and scratch (your head)’. It’s a little dated but I include it for completeness.

Collaboration and community are beautiful

Posted: January 14, 2016 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, aesthetics, authenticity, beauty, collaboration, collaborative learning, community, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, good, higher education, Ilove21C, in the student's head, learning, moocs, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, truth Leave a commentThere are many lessons to be learned from what is going on in the MOOC sector. The first is that we have a lot to learn, even for those of us who are committed to doing it ‘properly’ whatever that means. I’m not trying to convince you of “MOOC yes” or “MOOC no”. We can have that argument some other time. I’m talking about we already know from using these tools.

We’ve learned (again) that producing a broadcast video set of boring people reading the book at you in a monotone is, amazingly, not effective, no matter how fancy the platform. We know that MOOCs are predominantly taken by people who have already ‘succeeded’ at learning, often despite our educational system, and are thus not as likely to have an impact in traditionally disadvantaged areas, especially without an existing learning community and culture. (No references, you can Google all of this easily.)

We know that online communities can and do form. Ok, it’s not the same as twenty people in a room with you but our own work in this space confirms that you can have students experiencing a genuine feeling of belonging, facilitated through course design and forum interaction.

“Really?” you ask.

In a MOOC we ran with over 25,000 students, a student wrote a thank you note to us at the top of his code, for the final assignment. He had moved from non-coder to coder with us and had created some beautiful things. He left a note in his code because he thought that someone would read it. And we did. There is evidence of this everywhere in the forums and their code. No, we don’t have a face-to-face relationship. But we made them feel something and, from what we’ve seen so far, it doesn’t appear to be a bad something.

But we, as in the wider on-line community, have learned something else that is very important. Students in MOOCs often set their own expectations of achievement. They come in, find what they’re after, and leave, much like they are asking a question on Quora or StackExchange. Much like you check out reviews on-line before you start watching a show or you download one or two episodes to check it out. You know, 21st Century life.

Once you see that self-defined achievement and engagement, a lot of things about MOOCs, including drop rates and strange progression, suddenly make sense. As does the realisation that this is a total change from what we have accepted for centuries as desirable behaviour. This is something that we are going to have a lot of trouble fitting into our existing system. It also indicates how much work we’re going to have to do in order to bring in traditionally disadvantaged communities, first-in-family and any other under-represented group. Because they may still believe that we’re offering Perry’s nightmare in on-line form: serried ranks with computers screaming facts at you.

We offer our students a lot of choice but, as Universities, we mostly work on the idea of ‘follow this program to achieve this qualification’. Despite notionally being in the business of knowledge for the sake of knowledge, our non-award and ‘not for credit’ courses are dwarfed in enrolments by the ‘follow the track, get a prize’ streams. And that, of course, is where the diminishing bags of dollars come from. That’s why retention is such a hot-button issue at Universities because even 1% more retained students is worth millions to most Universities. A hunt and peck community? We don’t even know what retention looks like in that context.

Pretending that this isn’t happening is ignoring evidence. It’s self-deceptive, disingenuous, hypocritical (for we are supposed to be the evidence junkies) and, once again, we have a failure of educational aesthetics. Giving people what they don’t want isn’t good. Pretending that they just don’t know what’s good for them is really not being truthful. That’s three Socratic strikes: you’re out.

We had better be ready to redirect that energy or explode.

We have a message from our learning community. They want some control. We have to be aware that, if we really want them to do something, they have to feel that it’s necessary. (So much research supports this.) By letting them run around in the MOOC space, artificial and heavily instrumented, we can finally see what they’re up to without having to follow them around with clipboards. We see them on the massive scale, individuals and aggregates. Remember, on average these are graduates; these are students who have already been through our machine and come out. These are the last people, if we’ve convinced them of the rightness of our structure, who should be rocking the boat and wanting to try something different. Unless, of course, we haven’t quite been meeting their true needs all these years.

I often say that the problem we have with MOOC enrolments is that we can see all of them. There is no ‘peeking around the door’ in a MOOC. You’re in or you’re out, in order to be signed up for access or updates.

If we were collaborating with all of our students to produce learning materials and structures, not just the subset who go into MOOC, I wonder what we would end up turning out? We still need to apply our knowledge of pedagogy and psychology, of course, to temper desire with what works but I suspect that we should be collaborating with our learner community in a far more open way. Everywhere else, technology is changing the relationship between supplier and consumer. Name any other industry and we can probably find a new model where consumers get more choice, more knowledge and more power.

No-one (sensible) is saying we should raze the Universities overnight. I keep being told that allowing more student control is going to lead to terrible things but, frankly, I don’t believe it and I don’t think we have enough evidence to stop us from at least exploring this path. I think it’s scary, yes. I think it’s going to challenge how we think about tertiary education, absolutely. I also think that we need to work out how we can bring together the best of face-to-face with the best of on-line, for the most people, in the most educationally beautiful way. Because anything else just isn’t that beautiful.

Teaching for (current) Humans

Posted: January 13, 2016 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, briana morrison, community, design, education, educational research, edx, ethics, higher education, in the student's head, lauren margulieux, learning, mark guzdial, moocs, on-line learning, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, subgoals, teaching, teaching approaches, technology, thinking, tools, video 5 Comments

Leonardo’s experiments in human-octopus engineering never received appropriate recognition.

I was recently at a conference-like event where someone stood up and talked about video lectures. And these lectures were about 40 minutes long.

Over several million viewing sessions, EdX have clearly shown that watchable video length tops out at just over 6 minutes. And that’s the same for certificate-earning students and the people who have enrolled for fun. At 9 minutes, students are watching for fewer than 6 minutes. At the 40 minute mark, it’s 3-4 minutes.

I raised this point to the speaker because I like the idea that, if we do on-line it should be good on-line, and I got a response that was basically “Yes, I know that but I think the students should be watching these anyway.” Um. Six minutes is the limit but, hey, students, sit there for this time anyway.

We have never been able to unobtrusively measure certain student activities as well as we can today. I admit that it’s hard to measure actual attention by looking at video activity time but it’s also hard to measure activity by watching students in a lecture theatre. When we add clickers to measure lecture activity, we change the activity and, unsurprisingly, clicker-based assessment of lecture attentiveness gives us different numbers to observation of note-taking. We can monitor video activity by watching what the student actually does and pausing/stopping a video is a very clear signal of “I’m done”. The fact that students are less likely to watch as far on longer videos is a pretty interesting one because it implies that students will hold on for a while if the end is in sight.

In a lecture, we think students fade after about 15-20 minutes but, because of physical implications, peer pressure, politeness and inertia, we don’t know how many students have silently switched off before that because very few will just get up and leave. That 6 minute figure may be the true measure of how long a human will remain engaged in this kind of task when there is no active component and we are asking them to process or retain complex cognitive content. (Speculation, here, as I’m still reading into one of these areas but you see where I’m going.) We know that cognitive load is a complicated thing and that identifying subgoals of learning makes a difference in cognitive load (Morrison, Margulieux, Guzdial) but, in so many cases, this isn’t what is happening in those long videos, they’re just someone talking with loose scaffolding. Having designed courses with short videos I can tell you that it forces you, as the designer and teacher, to focus on exactly what you want to say and it really helps in making your points, clearly. Implicit sub-goal labelling, anyone? (I can hear Briana and Mark warming up their keyboards!)

If you want to make your videos 40 minutes long, I can’t stop you. But I can tell you that everything I know tells me that you have set your materials up for another hominid species because you’re not providing something that’s likely to be effective for current humans.

Musings of an Amateur Mythographer I: Islands of Certainty in a Sea of Confusion

Posted: June 23, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, Claude Lévi-Strauss, design, education, educational problem, educational research, evidence, higher education, Karl Popper, Lévi-Strauss, learning, moocs, myth, mythographer, reflection, resources, scientific thinking, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools Leave a commentI’ve been doing a lot of reading recently on the classification of knowledge, the development of scientific thinking, the ways different cultures approach learning, and the relationship between myths and science. Now, some of you are probably wondering why I can’t watch “Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.” like a normal person but others of you have already started to shift uneasily because I’ve talked about a relationship between myths and science, as if we do not consider science to be the natural successor to preceding myths. Well, let me go further. I’m about to start drawing on thinking on myths and science and even how the myths that teach us about the importance of evidence, the foundation of science, but for their own purposes.

Why?

Because much of what we face as opposition in educational research are pre-existing stereotypes and misconceptions that people employ, where there’s a lack of (and sometimes in the face of) evidence. Yet this collection of beliefs is powerful because it prevents people from adopting verified and validated approaches to learning and teaching. What can we call these? Are these myths? What do I even mean by that term?

It’s important to realise that the use of the term myth has evolved from earlier, rather condescending, classifications of any culture’s pre-scientific thinking as being dismissively primitive and unworthy of contemporary thought. This is a rich topic by itself but let me refer to Claude Lévi-Strauss and his identification of myth as being a form of thinking and classification, rather than simple story-telling, and thus proto-scientific, rather than anti-scientific. I note that I have done the study of mythology a grave disservice with such an abbreviated telling. Further reading here to understand precisely what Lévi-Strauss was refuting could involve Tylor, Malinowski, and Lévy-Bruhl. This includes rejecting a knee-jerk classification of a less scientifically advanced people as being emotional and practical, rather than (even being capable of) being intellectual. By moving myth forms to an intellectual footing, Lévi-Strauss allows a non-pejorative assessment of the potential value of myth forms.

In many situations, we consider myth and folklore as the same thing, from a Western post-Enlightenment viewpoint, only accepting those elements that we can validate. Thus, we choose not to believe that Olympus holds the Greek Pantheon as we cannot locate the Gods reliably, but the pre-scientific chewing of willow bark to relieve pain was validated once we constructed aspirin (and willow bark tea). It’s worth noting that the early location of willow bark as part of its scientific ‘discovery’ was inspired by an (effectively random) approach called the doctrine of signatures, which assumed that the cause and the cure of diseases would be located near each other. The folkloric doctrine of signatures led the explorers to a plant that tasted like another one but had a different use.

Myth, folklore and science, dancing uneasily together. Does this mean that what we choose to call myth now may or may not be myth in the future? We know that when to use it, to recommend it, in our endorsed and academic context is usually to require it to become science. But what is science?

Karl Popper’s (heavily summarised) view is that we have a set of hypotheses that we test to destruction and this is the foundation of our contemporary view of science. If the evidence we have doesn’t fit the hypothesis then we must reject the hypothesis. When we have enough evidence, and enough hypotheses, we have a supported theory. However, this has a natural knock-on effect in that we cannot actually prove anything, we just have enough evidence to support the hypothesis. Kuhn (again, heavily summarised) has a model of “normal science” where there is a large amount of science as in Popper’s model, incrementing a body of existing work, but there are times when this continuity gives way to a revolutionary change. At these times, we see an accumulation of contradictory evidence that illustrates that it’s time to think very differently about the world. Ultimately, we discover the need for a new coherency, where we need new exemplars to make the world make sense. (And, yes, there’s still a lot of controversy over this.)

Let me attempt to bring this all together, finally. We, as humans, live in a world full of information and some of it, even in our post-scientific world, we incorporate into our lives without evidence and some we need evidence to accept. Do you want some evidence that we live our lives without, or even in spite of, evidence? The median length for a marriage in the United States is 11 years and 40-50% of marriages will end in divorce yet many still swear ‘until death do us part’ or ‘all of my days’. But the myth of ‘marriage forever’ is still powerful. People have children, move, buy houses and totally change their lives based on this myth. The actions that people take here will have a significant impact on the world around them and yet it seems at odd with the evidence. (Such examples are not uncommon and, in a post-scientific revolution world, must force us to consider earlier suggestions that myth-based societies move seamlessly to a science-based intellectual utopia. This is why Lévi-Strauss is interesting to read. Our evidence is that our evidence is not sufficient evidence, so we must seek to better understand ourselves.) Even those components of our shared history and knowledge that are constructed to be based on faith, such as religion, understand how important evidence is to us. Let me give an example.

In the fourth book of the New Testament of the Christian Bible, the Gospel of John, we find the story of the Resurrection of Lazarus. Lazarus is sick and Jesus Christ waits until he dies to go to where he is buried and raise him. Jesus deliberately delays because the glory to the Christian God will be far greater and more will believe, if Lazarus is raised from the dead, rather than just healed from illness. Ultimately, and I do not speak for any religious figure or God here, anyone can get better from an illness but to be raised from the dead (currently) requires a miracle. Evidence, even in a book written for the faithful and to build faith, is important to humans.

We also know that there is a very large amount of knowledge that is accepted as being supported by evidence but the evidence is really anecdotal, based on bias and stereotype, and can even be distorted through repetition. This is the sea of confusion that we all live in. The scientific method (Popper) is one way that we can try to find firm ground to stand on but, if Kuhn is to be believed, there is the risk that one day we stand on the islands and realise that the truth was the sea all along. Even with Popper, we risk standing on solid ground that turns out to be meringue. How many of these changes can one human endure and still be malleable and welcoming in the face of further change?

Our problem with myth is when it forces us to reject something that we can demonstrate to be both valuable and scientifically valid because, right now, the world that we live in is constructed on scientific foundations and coherence is maintained by adding to those foundations. Personally, I don’t believe that myth and science have to be at odds (many disagree with me, including Richard Dawkins of course), and that this is an acceptable view as they are already co-existing in ways that actively shape society, for both good and ill.

Recently I made a comment on MOOCs that contradicted something someone said and I was (quite rightly) asked to provide evidence to support my assertions. That is the post before this one and what you will notice is that I do not have a great deal of what we would usually call evidence: no double-blind tests, no large-n trials with well-formed datasets. I had some early evidence of benefit, mostly qualitative and relatively soft, but, and this is important to me, what I didn’t have was evidence of harm. There are many myths around MOOCs and education in general. Some of them fall into the realm of harmful myths, those that cause people to reject good approaches to adhere to old and destructive practices. Some of them are harmful because they cause us to reject approaches that might work because we cannot find the evidence we need.

I am unsurprised that so many people adhere to folk pedagogy, given the vast amounts of information out there and the natural resistance to rejecting something that you think works, especially when someone sails in and tells you’ve been wrong for years. The fact that we are still discussing the nature of myth and science gives insight into how complicated this issue is.

I think that the path I’m on could most reasonably be called that of the mythographer, but the cataloguing of the edges of myth and the intersections of science is not in order to condemn one or the other but to find out what the truth is to the best of our knowledge. I think that understanding why people believe what they believe allows us to understand what they will need in order to believe something that is actually, well, true. There are many articles written on this, on the difficulty of replacing one piece of learning with another and the dangers of repetition in reinforcing previously-held beliefs, but there is hope in that we can construct new elements to replace old information if we are careful and we understand how people think.

We need to understand the delicate relationships between myth, folklore and science, our history as separate and joined peoples, if only to understand when we have achieved new forms of knowing. But we also need to be more upfront about when we believe we have moved on, including actively identifying areas that we have labelled as “in need of much more evidence” (such as learning styles, for example) to assist people in doing valuable work if they wish to pursue research.

I’ll go further. If we have areas where we cannot easily gain evidence, yet we have competing myths in that space, what should we do? How do we choose the best approach to achieve the most effective educational outcomes? I’ll let everyone argue in the comments for a while and then write that as the next piece.

Designing a MOOC: how far did it reach? #csed

Posted: June 10, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, computer science education, constructivist, contributing student pedagogy, curriculum, data visualisation, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, MOOC, moocs, principles of design, reflection, resources, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools Leave a commentMark Guzdial posted over on his blog on “Moving Beyond MOOCS: Could we move to understanding learning and teaching?” and discusses aspects (that still linger) of MOOC hype. (I’ve spoken about MOOCs done badly before, as well as recording the thoughts of people like Hugh Davis from Southampton.) One of Mark’s paragraphs reads:

“The value of being in the front row of a class is that you talk with the teacher. Getting physically closer to the lecturer doesn’t improve learning. Engagement improves learning. A MOOC puts everyone at the back of the class, listening only and doing the homework”

My reply to this was:

“You can probably guess that I have two responses here, the first is that the front row is not available to many in the real world in the first place, with the second being that, for far too many people, any seat in the classroom is better than none.

But I am involved in a, for us, large MOOC so my responses have to be regarded in that light. Thanks for the post!”

Mark, of course, called my bluff and responded with:

“Nick, I know that you know the literature in this space, and care about design and assessment. Can you say something about how you designed your MOOC to reach those who would not otherwise get access to formal educational opportunities? And since your MOOC has started, do you know yet if you achieved that goal — are you reaching people who would not otherwise get access?”

So here is that response. Thanks for the nudge, Mark! The answer is a bit long but please bear with me. We will be posting a longer summary after the course is completed, in a month or so. Consider this the unedited taster. I’m putting this here, early, prior to the detailed statistical work, so you can see where we are. All the numbers below are fresh off the system, to drive discussion and answering Mark’s question at, pretty much, a conceptual level.

First up, as some background for everyone, the MOOC team I’m working with is the University of Adelaide‘s Computer Science Education Research group, led by A/Prof Katrina Falkner, with me (Dr Nick Falkner), Dr Rebecca Vivian, and Dr Claudia Szabo.

I’ll start by noting that we’ve been working to solve the inherent scaling issues in the front of the classroom for some time. If I had a class of 12 then there’s no problem in engaging with everyone but I keep finding myself in rooms of 100+, which forces some people to sit away from me and also limits the number of meaningful interactions I can make to individuals in one setting. While I take Mark’s point about the front of the classroom, and the associated research is pretty solid on this, we encountered an inherent problem when we identified that students were better off down the front… and yet we kept teaching to rooms with more student than front. I’ll go out on a limb and say that this is actually a moral issue that we, as a sector, have had to look at and ignore in the face of constrained resources. The nature of large spaces and people, coupled with our inability to hover, means that we can either choose to have a row of students effectively in a semi-circle facing us, or we accept that after a relatively small number of students or number of rows, we have constructed a space that is inherently divided by privilege and will lead to disengagement.

So, Katrina’s and my first foray into this space was dealing with the problem in the physical lecture spaces that we had, with the 100+ classes that we had.

Katrina and I published a paper on “contributing student pedagogy” in Computer Science Education 22 (4), 2012, to identify ways for forming valued small collaboration groups as a way to promote engagement and drive skill development. Ultimately, by reducing the class to a smaller number of clusters and making those clusters pedagogically useful, I can then bring the ‘front of the class’-like experience to every group I speak to. We have given talks and applied sessions on this, including a special session at SIGCSE, because we think it’s a useful technique that reduces the amount of ‘front privilege’ while extending the amount of ‘front benefit’. (Read the paper for actual detail – I am skimping on summary here.)

We then got involved in the support of the national Digital Technologies curriculum for primary and middle school teachers across Australia, after being invited to produce a support MOOC (really a SPOC, small, private, on-line course) by Google. The target learners were teachers who were about to teach or who were teaching into, initially, Foundation to Year 6 and thus had degrees but potentially no experience in this area. (I’ve written about this before and you can find more detail on this here, where I also thanked my previous teachers!)

The motivation of this group of learners was different from a traditional MOOC because (a) everyone had both a degree and probable employment in the sector which reduced opportunistic registration to a large extent and (b) Australian teachers are required to have a certain number of professional development (PD) hours a year. Through a number of discussions across the key groups, we had our course recognised as PD and this meant that doing our course was considered to be valuable although almost all of the teachers we spoke to were furiously keen for this information anyway and my belief is that the PD was very much ‘icing’ rather than ‘cake’. (Thank you again to all of the teachers who have spent time taking our course – we really hope it’s been useful.)

To discuss access and reach, we can measure teachers who’ve taken the course (somewhere in the low thousands) and then estimate the number of students potentially assisted and that’s when it gets a little crazy, because that’s somewhere around 30-40,000.

In his talk at CSEDU 2014, Hugh Davis identified the student groups who get involved in MOOCs as follows. The majority of people undertaking MOOCs were life-long learners (older, degreed, M/F 50/50), people seeking skills via PD, and those with poor access to Higher Ed. There is also a small group who are Uni ‘tasters’ but very, very small. (I think we can agree that tasting a MOOC is not tasting a campus-based Uni experience. Less ivy, for starters.) The three approaches to the course once inside were auditing, completing and sampling, and it’s this final one that I want to emphasise because this brings us to one of the differences of MOOCs. We are not in control of when people decide that they are satisfied with the free education that they are accessing, unlike our strong gatekeeping on traditional courses.

I am in total agreement that a MOOC is not the same as a classroom but, also, that it is not the same as a traditional course, where we define how the student will achieve their goals and how they will know when they have completed. MOOCs function far more like many people’s experience of web browsing: they hunt for what they want and stop when they have it, thus the sampling engagement pattern above.

(As an aside, does this mean that a course that is perceived as ‘all back of class’ will rapidly be abandoned because it is distasteful? This makes the student-consumer a much more powerful player in their own educational market and is potentially worth remembering.)

Knowing these different approaches, we designed the individual subjects and overall program so that it was very much up to the participant how much they chose to take and individual modules were designed to be relatively self-contained, while fitting into a well-designed overall flow that built in terms of complexity and towards more abstract concepts. Thus, we supported auditing, completing and sampling, whereas our usual face-to-face (f2f) courses only support the first two in a way that we can measure.

As Hugh notes, and we agree through growing experience, marking/progress measures at scale are very difficult, especially when automated marking is not enough or not feasible. Based on our earlier work in contributing collaboration in the class room, for the F-6 Teacher MOOC we used a strong peer-assessment model where contributions and discussions were heavily linked. Because of the nature of the cohort, geographical and year-level groups formed who then conducted additional sessions and produced shared material at a slightly terrifying rate. We took the approach that we were not telling teachers how to teach but we were helping them to develop and share materials that would assist in their teaching. This reduced potential divisions and allows us to establish a mutually respectful relationship that facilitated openness.

(It’s worth noting that the courseware is creative commons, open and free. There are people reassembling the course for their specific take on the school system as we speak. We have a national curriculum but a state-focused approach to education, with public and many independent systems. Nobody makes any money out of providing this course to teachers and the material will always be free. Thank you again to Google for their ongoing support and funding!)

Overall, in this first F-6 MOOC, we had higher than usual retention of students and higher than usual participation, for the reasons I’ve outlined above. But this material was for curriculum support for teachers of young students, all of whom were pre-programming, and it could be contained in videos and on-line sharing of materials and discussion. We were also in the MOOC sweet-spot: existing degreed learners, PD driver, and their PD requirement depended on progressive demonstration on goal achievement, which we recognised post-course with a pre-approved certificate form. (Important note: if you are doing this, clear up how the PD requirements are met and how they need to be reported back, as early on as you can. It meant that we could give people something valuable in a short time.)

The programming MOOC, Think. Create. Code on EdX, was more challenging in many regards. We knew we were in a more difficult space and would be more in what I shall refer to as ‘the land of the average MOOC consumer’. No strong focus, no PD driver, no geographically guaranteed communities. We had to think carefully about what we considered to be useful interaction with the course material. What counted as success?

To start with, we took an image-based approach (I don’t think I need to provide supporting arguments for media-driven computing!) where students would produce images and, over time, refine their coding skills to produce and understand how to produce more complex images, building towards animation. People who have not had good access to education may not understand why we would use programming in more complex systems but our goal was to make images and that is a fairly universally understood idea, with a short production timeline and very clear indication of achievement: “Does it look like a face yet?”

In terms of useful interaction, if someone wrote a single program that drew a face, for the first time – then that’s valuable. If someone looked at someone else’s code and spotted a bug (however we wish to frame this), then that’s valuable. I think that someone writing a single line of correct code, where they understand everything that they write, is something that we can all consider to be valuable. Will it get you a degree? No. Will it be useful to you in later life? Well… maybe? (I would say ‘yes’ but that is a fervent hope rather than a fact.)

So our design brief was that it should be very easy to get into programming immediately, with an active and engaged approach, and that we have the same “mostly self-contained week” approach, with lots of good peer interaction and mutual evaluation to identify areas that needed work to allow us to build our knowledge together. (You know I may as well have ‘social constructivist’ tattooed on my head so this is strongly in keeping with my principles.) We wrote all of the materials from scratch, based on a 6-week program that we debated for some time. Materials consisted of short videos, additional material as short notes, participatory activities, quizzes and (we planned for) peer assessment (more on that later). You didn’t have to have been exposed to “the lecture” or even the advanced classroom to take the course. Any exposure to short videos or a web browser would be enough familiarity to go on with.

Our goal was to encourage as much engagement as possible, taking into account the fact that any number of students over 1,000 would be very hard to support individually, even with the 5-6 staff we had to help out. But we wanted students to be able to develop quickly, share quickly and, ultimately, comment back on each other’s work quickly. From a cognitive load perspective, it was crucial to keep the number of things that weren’t relevant to the task to a minimum, as we couldn’t assume any prior familiarity. This meant no installers, no linking, no loaders, no shenanigans. Write program, press play, get picture, share to gallery, winning.

As part of this, our support team (thanks, Jill!) developed a browser-based environment for Processing.js that integrated with a course gallery. Students could save their own work easily and share it trivially. Our early indications show that a lot of students jumped in and tried to do something straight away. (Processing is really good for getting something up, fast, as we know.) We spent a lot of time testing browsers, testing software, and writing code. All of the recorded materials used that development environment (this was important as Processing.js and Processing have some differences) and all of our videos show the environment in action. Again, as little extra cognitive load as possible – no implicit requirement for abstraction or skills transfer. (The AdelaideX team worked so hard to get us over the line – I think we may have eaten some of their brains to save those of our students. Thank you again to the University for selecting us and to Katy and the amazing team.)

The actual student group, about 20,000 people over 176 countries, did not have the “built-in” motivation of the previous group although they would all have their own levels of motivation. We used ‘meet and greet’ activities to drive some group formation (which worked to a degree) and we also had a very high level of staff monitoring of key question areas (which was noted by participants as being very high for EdX courses they’d taken), everyone putting in 30-60 minutes a day on rotation. But, as noted before, the biggest trick to getting everyone engaged at the large scale is to get everyone into groups where they have someone to talk to. This was supposed to be provided by a peer evaluation system that was initially part of the assessment package.

Sadly, the peer assessment system didn’t work as we wanted it to and we were worried that it would form a disincentive, rather than a supporting community, so we switched to a forum-based discussion of the works on the EdX discussion forum. At this point, a lack of integration between our own UoA programming system and gallery and the EdX discussion system allowed too much distance – the close binding we had in the R-6 MOOC wasn’t there. We’re still working on this because everything we know and all evidence we’ve collected before tells us that this is a vital part of the puzzle.

In terms of visible output, the amount of novel and amazing art work that has been generated has blown us all away. The degree of difference is huge: armed with approximately 5 statements, the number of different pieces you can produce is surprisingly large. Add in control statements and reputation? BOOM. Every student can write something that speaks to her or him and show it to other people, encouraging creativity and facilitating engagement.

From the stats side, I don’t have access to the raw stats, so it’s hard for me to give you a statistically sound answer as to who we have or have not reached. This is one of the things with working with a pre-existing platform and, yes, it bugs me a little because I can’t plot this against that unless someone has built it into the platform. But I think I can tell you some things.

I can tell you that roughly 2,000 students attempted quiz problems in the first week of the course and that over 4,000 watched a video in the first week – no real surprises, registrations are an indicator of interest, not a commitment. During that time, 7,000 students were active in the course in some way – including just writing code, discussing it and having fun in the gallery environment. (As it happens, we appear to be plateauing at about 3,000 active students but time will tell. We have a lot of post-course analysis to do.)

It’s a mistake to focus on the “drop” rates because the MOOC model is different. We have no idea if the people who left got what they wanted or not, or why they didn’t do anything. We may never know but we’ll dig into that later.

I can also tell you that only 57% of the students currently enrolled have declared themselves explicitly to be male and that is the most likely indicator that we are reaching students who might not usually be in a programming course, because that 43% of others, of whom 33% have self-identified as women, is far higher than we ever see in classes locally. If you want evidence of reach then it begins here, as part of the provision of an environment that is, apparently, more welcoming to ‘non-men’.

We have had a number of student comments that reflect positive reach and, while these are not statistically significant, I think that this also gives you support for the idea of additional reach. Students have been asking how they can save their code beyond the course and this is a good indicator: ownership and a desire to preserve something valuable.

For student comments, however, this is my favourite.

I’m no artist. I’m no computer programmer. But with this class, I see I can be both. #processingjs (Link to student’s work) #code101x .

That’s someone for whom this course had them in the right place in the classroom. After all of this is done, we’ll go looking to see how many more we can find.

I know this is long but I hope it answered your questions. We’re looking forward to doing a detailed write-up of everything after the course closes and we can look at everything.

Think. Create. Code. Vis! (@edXOnline, @UniofAdelaide, @cserAdelaide, @code101x, #code101x)

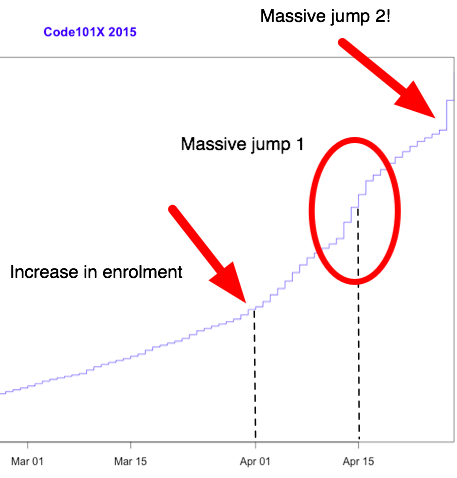

Posted: April 30, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: #code101x, advocacy, blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, data visualisation, education, educational problem, educational research, edx, higher education, learning, measurement, MOOC, moocs, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design Leave a commentI just posted about the massive growth in our new on-line introductory programming course but let’s look at the numbers so we can work out what’s going on and, maybe, what led to that level of success. (Spoilers: central support from EdX helped a huge amount.) So let’s get to the data!

I love visualised data so let’s look at the growth in enrolments over time – this is really simple graphical stuff as we’re spending time getting ready for the course at the moment! We’ve had great support from the EdX team through mail-outs and Twitter and you can see these in the ‘jumps’ in the data that occurred at the beginning, halfway through April and again at the end. Or can you?

Hmm, this is a large number, so it’s not all that easy to see the detail at the end. Let’s zoom in and change the layout of the data over to steps so we can things more easily. (It’s worth noting that I’m using the free R statistical package to do all of this. I can change one line in my R program and regenerate all of my graphs and check my analysis. When you can program, you can really save time on things like this by using tools like R.)

Now you can see where that increase started and then the big jump around the time that e-mail advertising started, circled. That large spike at the end is around 1500 students, which means that we jumped 10% in a day.

When we started looking at this data, we wanted to get a feeling for how many students we might get. This is another common use of analysis – trying to work out what is going to happen based on what has already happened.

As a quick overview, we tried to predict the future based on three different assumptions:

- that the growth from day to day would be roughly the same, which is assuming linear growth.

- that the growth would increase more quickly, with the amount of increase doubling every day (this isn’t the same as the total number of students doubling every day).

- that the growth would increase even more quickly than that, although not as quickly as if the number of students were doubling every day.

If Assumption 1 was correct, then we would expect the graph to look like a straight line, rising diagonally. It’s not. (As it is, this model predicted that we would only get 11,780 students. We crossed that line about 2 weeks ago.

So we know that our model must take into account the faster growth, but those leaps in the data are changes that caused by things outside of our control – EdX sending out a mail message appears to cause a jump that’s roughly 800-1,600 students, and it persists for a couple of days.

Let’s look at what the models predicted. Assumption 2 predicted a final student number around 15,680. Uhh. No. Assumption 3 predicted a final student number around 17,000, with an upper bound of 17,730.

Hmm. Interesting. We’ve just hit 17,571 so it looks like all of our measures need to take into account the “EdX” boost. But, as estimates go, Assumption 3 gave us a workable ballpark and we’ll probably use it again for the next time that we do this.

Now let’s look at demographic data. We now we have 171-172 countries (it varies a little) but how are we going for participation across gender, age and degree status? Giving this information to EdX is totally voluntary but, as long as we take that into account, we make some interesting discoveries.

Our median student age is 25, with roughly 40% under 25 and roughly 40% from 26 to 40. That means roughly 20% are 41 or over. (It’s not surprising that the graph sits to one side like that. If the left tail was the same size as the right tail, we’d be dealing with people who were -50.)

The gender data is a bit harder to display because we have four categories: male, female, other and not saying. In terms of female representation, we have 34% of students who have defined their gender as female. If we look at the declared male numbers, we see that 58% of students have declared themselves to be male. Taking into account all categories, this means that our female participant percentage could be as high as 40% but is at least 34%. That’s much higher than usual participation rates in face-to-face Computer Science and is really good news in terms of getting programming knowledge out there.

We’re currently analysing our growth by all of these groupings to work out which approach is the best for which group. Do people prefer Twitter, mail-out, community linkage or what when it comes to getting them into the course.

Anyway, lots more to think about and many more posts to come. But we’re on and going. Come and join us!

Think. Create. Code. Wow! (@edXOnline, @UniofAdelaide, @cserAdelaide, @code101x, #code101x)

Posted: April 30, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: #code101x, advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, cser digital technologies, curriculum, digital technologies, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, higher education, Hugh Davis, learning, MOOC, moocs, on-line learning, research, Southampton, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, University of Southampton 1 CommentThings are really exciting here because, after the success of our F-6 on-line course to support teachers for digital technologies, the Computer Science Education Research group are launching their first massive open on-line course (MOOC) through AdelaideX, the partnership between the University of Adelaide and EdX. (We’re also about to launch our new 7-8 course for teachers – watch this space!)

Our EdX course is called “Think. Create. Code.” and it’s open right now for Week 0, although the first week of real content doesn’t go live until the 30th. If you’re not already connected with us, you can also follow us on Facebook (code101x) or Twitter (@code101x), or search for the hashtag #code101x. (Yes, we like to be consistent.)

I am slightly stunned to report that, less than 24 hours before the first content starts to roll out, that we have 17,531 students enrolled, across 172 countries. Not only that, but when we look at gender breakdown, we have somewhere between 34-42% women (not everyone chooses to declare a gender). For an area that struggles with female participation, this is great news.

I’ll save the visualisation data for another post, so let’s quickly talk about the MOOC itself. We’re taking a 6 week approach, where students focus on developing artwork and animation using the Processing language, but it requires no prior knowledge and runs inside a browser. The interface that has been developed by the local Adelaide team (thank you for all of your hard work!) is outstanding and it’s really easy to make things happen.

I love this! One of the biggest obstacles to coding is having to wait until you see what happens and this can lead to frustration and bad habits. In Processing you can have a circle on the screen in a matter of seconds and you can start playing with colour in the next second. There’s a lot going on behind the screen to make it this easy but the student doesn’t need to know it and can get down to learning. Excellent!

I went to a great talk at CSEDU last year, presented by Hugh Davis from Southampton, where Hugh raised some great issues about how MOOCs compared to traditional approaches. I’m pleased to say that our demography is far more widespread than what was reported there. Although the US dominates, we have large representations from India, Asia, Europe and South America, with a lot of interest from Africa. We do have a lot of students with prior degrees but we also have a lot of students who are at school or who aren’t at University yet. It looks like the demography of our programming course is much closer to the democratic promise of free on-line education but we’ll have to see how that all translates into participation and future study.

While this is an amazing start, the whole team is thinking of this as part of a project that will be going on for years, if not decades.

When it came to our teaching approach, we spent a lot of time talking (and learning from other people and our previous attempts) about the pedagogy of this course: what was our methodology going to be, how would we implement this and how would we make it the best fit for this approach? Hugh raised questions about the requirement for pedagogical innovation and we think we’ve addressed this here through careful customisation and construction (we are working within a well-defined platform so that has a great deal of influence and assistance).

We’ve already got support roles allocated to staff and students will see us on the course, in the forums, and helping out. One of the reasons that we tried to look into the future for student numbers was to work out how we would support students at this scale!

One of our most important things to remember is that completion may not mean anything in the on-line format. Someone comes on and gets an answer to the most pressing question that is holding them back from coding, but in the first week? That’s great. That’s success! How we measure that, and turn that into traditional numbers that match what we do in face-to-face, is going to be something we deal with as we get more information.

The whole team is raring to go and the launch point is so close. We’re looking forward to working with thousands of students, all over the world, for the next six weeks.

Sound interesting? Come and join us!

Large Scale Authenticity: What I Learned About MOOCs from Reality Television

Posted: March 8, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, design, education, ethics, feedback, games, higher education, MKR, moocs, My Kitchen Rules, principles of design, reflection, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking 1 CommentThe development of social media platforms has allows us to exchange information and, well, rubbish very easily. Whether it’s the discussion component of a learning management system, Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Snapchat or whatever will be the next big thing, we can now chat to each other in real time very, very easily.

One of the problems with any on-line course is trying to maintain a community across people who are not in the same timezone, country or context. What we’d really like is for the community communication to come from the students, with guidance and scaffolding from the lecturing staff, but sometimes there’s priming, leading and… prodding. These “other” messages have to be carefully crafted and they have to connect with the students or they risk being worse than no message at all. As an example, I signed up for an on-line course and then wasn’t able to do much in the first week. I was sitting down to work on it over the weekend when a mail message came in from the organisers on the community board congratulating me on my excellent progress on things I hadn’t done. (This wasn’t isolated. The next year, despite not having signed up, the same course sent me even more congratulations on totally non-existent progress.) This sends the usual clear messages that we expect from false praise and inauthentic communication: the student doesn’t believe that you know them, they don’t feel part of an authentic community and they may disengage. We have, very effectively, sabotaged everything that we actually wanted to build.

Let’s change focus. For a while, I was watching a show called “My Kitchen Rules” on local television. It pretends to be about cooking (with competitive scoring) but it’s really about flogging products from a certain supermarket while delivering false drama in the presence of dangerously orange chefs. An engineered activity to ensure that you replace an authentic experience with consumerism and commodities? Paging Guy Debord on the Situationist courtesy phone: we have a Spectacle in progress. What makes the show interesting is the associated Twitter feed, where large numbers of people drop in on the #mkr to talk about the food, discuss the false drama, exchange jokes and develop community memes, such as sharing pet pictures with each other over the (many) ad breaks. It’s a community. Not everyone is there for the same reasons: some are there to be rude about people, some are actually there for the cooking (??) and some are… confused. But the involvement in the conversation, interplay and development of a shared reality is very real.

And this would all be great except for one thing: Australia is a big country and spans a lot of timezones. My Kitchen Rules is broadcast at 7:30pm, starting in Melbourne, Canberra, Tasmania and Sydney, then 30 minutes later in Adelaide, then 30 minutes later again in Queensland (they don’t do daylight savings), then later again for Perth. So now we have four different time groups to manage, all watching the same show.

But the Twitter feed starts on the first time point, Adelaide picks up discussions from the middle of the show as they’re starting and then gets discussions on scores as the first half completes for them… and this is repeated for Queensland viewers and then for Perth. Now , in the community itself, people go on and off the feed as their version of the show starts and stops and, personally, I don’t find score discussions very distracting because I’m far more interested in the Situation being created in the Twitter stream.

Enter the “false tweets” of the official MKR Social Media team who ask questions that only make sense in the leading timezone. Suddenly, everyone who is not quite at the same point is then reminded that we are not in the same place. What does everyone think of the scores? I don’t know, we haven’t seen it yet. What’s worse are the relatively lame questions that are being asked in the middle of an actual discussion that smell of sponsorship involvement or an attempt to produce the small number of “acceptable” tweets that are then shared back on the TV screen for non-connected viewers. That’s another thing – everyone outside of the first timezone has very little chance of getting their Tweet displayed. Imagine if you ran a global MOOC where only the work of the students in San Francisco got put up as an example of good work!

This is a great example of an attempt to communicate that fails dismally because it doesn’t take into account how people are using the communications channel, isn’t inclusive (dismally so) and constantly reminds people who don’t live in a certain area that they really aren’t being considered by the program’s producers.

You know what would fix it? Putting it on at the same time everywhere but that, of course, is tricky because of the way that advertising is sold and also because it would force poor Perth to start watching dinner television just after work!

But this is a very important warning of what happens when you don’t think about how you’ve combined the elements of your environment. It’s difficult to do properly but it’s terrible when done badly. And I don’t need to go and enrol in a course to show you this – I can just watch a rather silly cooking show.

MOOCs and the on-line Masters Degree

Posted: September 10, 2014 Filed under: Education | Tags: blogging, community, education, educational research, georgia tech, higher education, measurement, moocs, on-line learning, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentThere’s been a lot of interest in Georgia Tech’s new on-line masters degree in Computer Science, offered jointly with Udacity and AT&T. The first offering ran with 375 students, and there are 500 in the pipeline, but readmissions opened again two days ago so this number has probably gone up. PBS published an article recently, written up on the ACM blog.

I think we’re all watching this with interest as, while it’s neither Massive at this scale or Open (fee-paying and admission checked), if this works reasonably, let alone well, then we have something new to offer at the tertiary scale but without many of the problems that we’ve traditionally seen with existing MOOCs (retention, engagement, completion and accreditation.)

Right now, there are some early observations: the students are older (11 years older on average) and most are working. In this way, we’re much closer to the standard MOOC demographic for success: existing degree, older and practised in work. We would expect this course to do relatively well, much as our own experiences with on-line learning at the 100s scale worked well for that demographic. This is, unlike ours, more tightly bound into Georgia’s learning framework and their progress pathways, so we are very keen to see how their success will translate to other areas.

We are still learning about where MOOC (and its children SPOC and the Georgia Tech program) will end up in the overall scheme of education. With this program, we stand a very chance of working out exactly what it means to us in the traditional higher educational sector.

ITiCSE 2014, Monday, Session 1A, Technology and Learning, #ITiCSE2014 #ITiCSE @patitsel @guzdial

Posted: June 23, 2014 Filed under: Education | Tags: badges, computer science education, data visualisation, digital education, digital technologies, education, game development, gamification, higher education, ITiCSE, ITiCSE 2014, learning, moocs, PBL, projected based learning, SPOCs, teaching, technology, thinking, visualisation Leave a comment(The speakers are going really. really quickly so apologies for any errors or omissions that slip through.)

The chair had thanked the Spanish at the opening for the idea of long coffee breaks and long lunches – a sentiment I heartily share as it encourages discussions, which are the life blood of good conferences. The session opened with “SPOC – supported introduction to Programming” presented by Marco Piccioni. SPOCs are Small Private On-line Courses and are part of the rich tapestry of hand-crafted terminology that we are developing around digital delivery. The speaker is from ETH-Zurich and says that they took a cautious approach to go step-by-step in taking an existing and successful course and move it into the on-line environment. The classic picture from University of Bologna of the readers/scribes was shown. (I was always the guy sleeping in the third row.)

We want our teaching to be interesting and effective so there’s an obis out motivation to get away from this older approach. ETH has an interesting approach where the exam is 10 months after the lecture, which leads to interesting learning strategies for students who can’t solve the instrumentality problem of tying work now into success in the future. Also, ETH had to create an online platform to get around all of the “my machine doesn’t work” problems that would preclude the requirement to install an IDE. The final point of motivation was to improve their delivery.

The first residential version of the course ran in 2003, with lectures and exercise sessions. The lectures are in German and the exercise sessions are in English and German, because English is so dominant in CS. There are 10 extensive home assignments including programming and exercise sessions groups formed according to students’ perceived programming proficiency level. (Note on the last point: Hmmm, so people who can’t program are grouped together with other people who can’t program? I believe that the speaker clarifies this as “self-perceived” ability but I’m still not keen on this kind of streaming. If this worked effectively, then any master/apprentice model should automatically fail) Groups were able to switch after a week, for language or not working with the group.

The learning platform for the activity was Moodle and their experience with it was pretty good, although it didn’t do everything that they wanted. (They couldn’t put interactive sessions into a lecture, so they produced a lecture-quiz plug-in for Moodle. That’s very handy.) This is used in conjunction with a programming assessment environment, in the cloud, which ties together the student performance at programming with the LMS back-end.

The SPOC components are:

- lectures, with short intros and video segments up to 17 minutes. (Going to drop to 10 minutes based on student feedback),

- quizzes, during lectures, testing topic understanding immediately, and then testing topic retention after the lecture,

- programming exercises, with hands-on practice and automatic feedback

Feedback given to the students included the quizzes, with a badge for 100% score (over unlimited attempts so this isn’t as draconian as it sounds), and a variety of feedback on programming exercises, including automated feedback (compiler/test suite based on test cases and output matching) and a link to a suggested solution. The predefined test suite was gameable (you could customise your code for the test suite) and some students engineered their output to purely match the test inputs. This kind of cheating was deemed to be not a problem by ETH but it was noted that this wouldn’t scale into MOOCs. Note that if someone got everything right then they got to see the answer – so bad behaviour then got you the right answer. We’re all sadly aware that many students are convinced that having access to some official oracle is akin to having the knowledge themselves so I’m a little cautious about this as a widespread practice: cheat, get right answer, is a formula for delayed failure.

Reporting for each student included their best attempt and past attempts. For the TAs, they had a wider spread of metrics, mostly programmatic and mark-based.

On looking at the results, the attendance to on-line lectures was 71%, where the live course attendance remained stable. Neither on-line quizzes nor programming exercises counted towards the final grade. Quiz attempts were about 5x the attendance and 48% got 100% and got the badge, significantly more than the 5-10% than would usually do this.

Students worked on 50% of the programming exercises. 22% of students worked on 75-100% of the exercises. (There was a lot of emphasis on the badge – and I’m really not sure if there’s evidence to support this.)

The lessons learned summarised what I’ve put above: shortening video lengths, face-to-face is important, MCQs can be creative, ramification, and better feedback is required on top of the existing automatic feedback.

The group are scaling from SPOC to MOOC with a Computing: Art, Magic, Science course on EdX launching later on in 2014.

I asked a question about the badges because I was wondering if putting in the statement “100% in the quiz is so desirable that I’ll give you a badge” was what had led to the improved performance. I’m not sure I communicated that well but, as I suspected, the speaker wants to explore this more in later offerings and look at how this would scale.

The next session was “Teaching and learning with MOOCs: Computing academics’ perspectives and engagement”, presented by Anna Eckerdal. The work was put together by a group composed from Uppsala, Aalto, Maco and Monash – which illustrates why we all come to conferences as this workgroup was put together in a coffee-shop discussion in Uppsala! The discussion stemmed from the early “high hype” mode of MOOCs but they were highly polarising as colleagues either loved it or hated it. What was the evidence to support either argument? Academics’ experience and views on MOOCs were sought via a questionnaire sent out to the main e-mail lists, to CS and IT people.

The study ran over June-JUly 2013, with 236 responses, over > 90 universities, and closed- and open-ended questions. What were the research questions: What are the community views on MOOC from a teaching perspective (positive and negative) and how have people been incorporating them into their existing courses? (Editorial note: Clearly defined study with a precise pair of research questions – nice.)

Interestingly, more people have heard concern expressed about MOOCs, followed by people who were positive, then confused, the negative, then excited, then uninformed, then uninterested and finally, some 10% of people who have been living in a time-travelling barrel in Ancient Greece because in 2013 they have heard no MOOC discussion.

Several themes were identified as prominent themes in the positive/negative aspects but were associated with the core them of teaching and learning. (The speaker outlined the way that the classification had been carried out, which is always interesting for a coding problem.) Anna reiterated the issue of a MOOC as a personal power enhancer: a MOOC can make a teacher famous, which may also be attractive to the Uni. The sub themes were pedagogy and learning env, affordance of MOOCs, interaction and collaboration, assessment and certificates, accessibility.

Interestingly, some of the positive answers included references to debunked approaches (such as learning styles) and the potential for improvements. The negatives (and there were many of them) referred to stone age learning and ack of relations.

On affordances of MOOCs, there were mostly positive comments: helping students with professional skills, refresh existing and learn new skills, try before they buy and the ability to transcend the tyranny of geography. The negatives included the economic issues of only popular courses being available, the fact that not all disciplines can go on-line, that there is no scaffolding for identity development in the professional sense nor support development of critical thinking or teamwork. (Not sure if I agree with the last two as that seems to be based on the way that you put the MOOC together.)

I’m afraid I missed the slide on interaction and collaboration so you’ll (or I’ll) have to read the paper at some stage.

There was nothing positive about assessment and certificates: course completion rates are low, what can reasonably be assessed, plagiarism and how we certify this. How does a student from a MOOC compete with a student from a face-to-face University.

1/3 of the respondents answered about accessibility, with many positive comments on “Anytime. anywhere, at one’s own pace”. We can (somehow) reach non-traditional student groups. (Note: there is a large amount of contradictory evidence on this one, MOOCs are even worse than traditional courses. Check out Mark Guzdial’s CACM blog on this.) Another answer was “Access to world class teachers” and “opportunity to learn from experts in the field.” Interesting, given that the mechanism (from other answers) is so flawed that world-class teachers would barely survive MOOC ification!

On Academics’ engagement with MOOCs, the largest group (49%) believed that MOOCs had had no effect at all, about 15% said it had inspired changes, roughly 10% had incorporated some MOOCs. Very few had seen MOOCs as a threat requiring change: either personally or institutionally. Only one respondent said that their course was a now a MOOC, although 6% had developed them and 12% wanted to.

For the open-ended question on Academics’ engagement, most believed that no change was required because their teaching was superior. (Hmm.) A few reported changes to teaching that was similar to MOOCs (on line materials or automated assessment) but wasn’t influenced by them.

There’s still no clear vision of the role of MOOCs in the future: concerned is as prominent as positive. There is a lot of potential but many concerns.

The authors had several recommendations of concern: focusing on active learning, we need a lot more search in automatic assessment and feedback methods, and there is a need for lots of good policy from the Universities regarding certification and the role of on-site and MOOC curricula. Uppsala have started the process of thinking about policy.

The first question was “how much of what is seen here would apply to any new technology being introduced” with an example of the similar reactions seen earlier to “Second Life”. Anna, in response, wondered why MOOC has such a global identity as a game-changer, given its similarity to previous technologies. The global discussion leads to the MOOC topic having a greater influence, which is why answering these questions is more important in this context. Another issue raised in questions included the perceived value of MOOCs, which means that many people who have taken MOOCs may not be advertising it because of the inherent ranking of knowledge.

@patitsel raised the very important issue that under-represented groups are even more under-represented in MOOCs – you can read through Mark’s blog to find many good examples of this, from cultural issues to digital ghettoisation.

The session concluded with “Augmenting PBL with Large Public Presentations: A Case Study in Interactive Graphics Pedagogy”. The presenter was a freshly graduated student who had completed the courses three weeks ago so he was here to learn and get constructive criticism. (Ed’s note: he’s in the right place. We’re very inquisitive.)

Ooh, brave move. He’s starting with anecdotal evidence. This is not really the crowd for that – we’re happy with phenomenographic studies and case studies to look at the existence of phenomena as part of a study, but anecdotes, even with pictures, are not the best use of your short term in front of a group of people. And already a couple of people have left because that’s not a great way to start a talk in terms of framing.

I must be honest, I slightly lost track of the talk here. EBL was defined as project-based learning augmented with constructively aligned public expos, with gamers as the target audience. The speaker noted that “gamers don’t wait” as a reason to have strict deadlines. Hmm. Half Life 3 anyone? The goal was to study the pedagogical impact of this approach. The students in the study had to build something large, original and stable, to communicate the theory, work as a group, demonstrate in large venues and then collaborate with a school of communication. So, it’s a large-scale graphics-based project in teams with a public display.

…

Grading was composed of proposals, demos, presentation and open houses. Two projects (50% and 40%) and weekly assignments (10%) made up the whole grading scheme. The second project came out after the first big Game Expo demonstration. Project 1 had to be interactive groups, in groups of 3-4. The KTH visualisation studio was an important part of this and it is apparently full of technology, which is nice and we got to hear about a lot of it. Collaboration is a strong part of the visualisation studio, which was noted in response to the keynote. The speaker mentioned some of the projects and it’s obvious that they are producing some really good graphics projects.

I’ll look at the FaceUp application in detail as it was inspired by the idea to make people look up in the Metro rather than down at their devices. I’ll note that people look down for a personal experience in shared space. Projecting, even up, without capturing the personalisation aspect, is missing the point. I’ll have to go and look at this to work out if some of these issues were covered in the FaceUp application as getting people to look up, rather than down, needs to have a strong motivating factor if you’re trying to end digitally-inspired isolation.

The experiment was to measure the impact on EXPOs on ILOs, using participation, reflection, surveys and interviews. The speaker noted that doing coding on a domain of knowledge you feel strongly about (potentially to the point of ownership) can be very hard as biases creep in and I find it one of the real challenges in trying to do grounded theory work, personally. I’m not all that surprised that students felt that the EXPO had a greater impact than something smaller, especially where the experiment was effectively created with a larger weight first project and a high-impact first deliverable. In a biological human sense, project 2 is always going to be at risk of being in the refectory period, the period after stimulation during which a nerve or muscle is less able to be stimulated. You can get as excited about the development, because development is always going to be very similar, but it’s not surprising that a small-scale pop is not as exciting as a giant boom, especially when the boom comes first.

How do we grade things like this? It’s a very good question – of course the first question is why are we grading this? Do we need to be able to grade this sort of thing or just note that it’s met a professional standard? How can we scale this sort of thing up, especially when the main function of the coordinator is as a cheerleader and relationships are essential. Scaling up relationships is very, very hard. Talking to everyone in a group means that the number of conversations you have is going to grow at an incredibly fast rate. Plus, we know that we have an upper bound on the number of relationships we can actually have – remember Dunbar’s number of 120-150 or so? An interesting problem to finish on.