What are we assessing? How?

Posted: January 16, 2016 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: aesthetics, authenticity, beauty, Bloom, eckerdal, education, educational problem, educational research, eric mazur, ethics, higher education, in the student's head, learning, neopiaget, principles of design, resources, SOLO, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentHow we can create a better assessment system, without penalties, that works in a grade-free environment? Let’s provide a foundation for this discussion by looking at assessment today.

Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy

We have many different ways of understanding exactly how we are assessing knowledge. Bloom’s taxonomy allows us to classify the objectives that we set for students, in that we can determine if we’re just asking them to remember something, explain it, apply it, analyse it, evaluate it or, having mastered all of those other aspects, create a new example of it. We’ve also got Bigg’s SOLO taxonomy to classify levels of increasing complexity in a student’s understanding of subjects. Now let’s add in threshold concepts, learning edge momentum, neo-Piagetian theory and …

Let’s summarise and just say that we know that students take a while to learn things, can demonstrate some convincing illusions of progress that quickly fall apart, and that we can design our activities and assessment in a way that acknowledges this.

I attended a talk by Eric Mazur, of Peer Instruction fame, and he said a lot of what I’ve already said about assessment not working with how we know we should be teaching. His belief is that we rarely rise above remembering and understanding, when it comes to testing, and he’s at Harvard, where everyone would easily accept their practices as, in theory, being top notch. Eric proposed a number of approaches but his focus on outcomes was one that I really liked. He wanted to keep the coaching role he could provide separate from his evaluator role: another thing I think we should be doing more.

Eric is in Physics but all of these ideas have been extensively explored in my own field, especially where we start to look at which of the levels we teach students to and then what we assess. We do a lot of work on this in Australia and here is some work by our groups and others I have learned from:

- Szabo, C., Falkner, K. & Falkner, N. 2014, ‘Experiences in Course Design using Neo-Piagetian Theory’

- Falkner, K., Vivian, R., Falkner, N., 2013, ‘Neo-piagetian Forms of Reasoning in Software Development Process Construction’

- Whalley, J., Lister, R.F., Thompson, E., Clear, T., Robbins, P., Kumar, P. & Prasad, C. 2006, ‘An Australasian study of reading and comprehension skills in novice programmers, using Bloom and SOLO taxonomies’

- Gluga, R., Kay, J., Lister, R.F. & Teague, D. 2012, ‘On the reliability of classifying programming tasks using a neo-piagetian theory of cognitive development’

I would be remiss to not mention Anna Eckerdal’s work, and collaborations, in the area of threshold concepts. You can find her many papers on determining which concepts are going to challenge students the most, and how we could deal with this, here.

Let me summarise all of this:

- There are different levels at which students will perform as they learn.

- It needs careful evaluation to separate students who appear to have learned something from students who have actually learned something.

- We often focus too much on memorisation and simple explanation, without going to more advanced levels.

- If we want to assess advanced levels, we may have to give up the idea of trying to grade these additional steps as objectivity is almost impossible as is task equivalence.

- We should teach in a way that supports the assessment we wish to carry out. The assessment we wish to carry out is the right choice to demonstrate true mastery of knowledge and skills.

If we are not designing for our learning outcomes, we’re unlikely to create courses to achieve those outcomes. If we don’t take into account the realities of student behaviour, we will also fail.

We can break our assessment tasks down by one of the taxonomies or learning theories and, from my own work and that of others, we know that we will get better results if we provide a learning environment that supports assessment at the desired taxonomic level.

But, there is a problem. The most descriptive, authentic and open-ended assessments incur the most load in terms of expert human marking. We don’t have a lot of expert human markers. Overloading them is not good. Pretending that we can mark an infinite number of assignments is not true. Our evaluation aesthetics are objectivity, fairness, effectiveness, timeliness and depth of feedback. Assignment evaluation should be useful to the students, to show progress, and useful to us, to show the health of the learning environment. Overloading the marker will compromise the aesthetics.

Our beauty lens tells us very clearly that we need to be careful about how we deal with our finite resources. As Eric notes, and we all know, if we were to test simpler aspects of student learning, we can throw machines at it and we have a near infinite supply of machines. I cannot produce more experts like me, easily. (Snickers from the audience) I can recruit human evaluators from my casual pool and train them to mark to something like my standard, using a rubric or using an approximation of my approach.

Thus I have a framework of assignments, divide by level, and I appear to have assignment evaluation resources. And the more expert and human the marker, the more … for want of a better word … valuable the resource. The better feedback it can produce. Yet the more valuable the resource, the less of it I have because it takes time to develop evaluation skills in humans.

Tune in tomorrow for the penalty free evaluation and feedback that ties all of this together.

Assessment is (often) neither good nor true.

Posted: January 9, 2016 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, aesthetics, beauty, community, design, education, ethics, higher education, in the student's head, kohn, principles of design, rapaport, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design, work/life balance, workload 3 CommentsIf you’ve been reading my blog over the past years, you’ll know that I have a lot of time for thinking about assessment systems that encourage and develop students, with an emphasis on intrinsic motivation. I’m strongly influenced by the work of Alfie Kohn, unsurprisingly given I’ve already shown my hand on Focault! But there are many other writers who are… reassessing assessment: why we do it, why we think we are doing it, how we do it, what actually happens and what we achieve.

In my framing, I want assessment to be as all other aspects of education: aesthetically satisfying, leading to good outcomes and being clear and what it is and what it is not. Beautiful. Good. True. There are some better and worse assessment approaches out there and there are many papers discussing this. One of these that I have found really useful is Rapaport’s paper on a simplified assessment process for consistent, fair and efficient grading. Although I disagree with some aspects, I consider it to be both good, as it is designed to clearly address a certain problem to achieve good outcomes, and it is true, because it is very honest about providing guidance to the student as to how well they have met the challenge. It is also highly illustrative and honest in representing the struggle of the author in dealing with the collision of novel and traditional assessment systems. However, further discussion of Rapaport is for the near future. Let me start by demonstrating how broken things often are in assessment, by taking you through a hypothetical situation.

Thought Experiment 1

Two students, A and B, are taking the same course. There are a number of assignments in the course and two exams. A and B, by sheer luck, end up doing no overlapping work. They complete different assignments to each other, half each and achieve the same (cumulative bare pass overall) marks. They then manage to score bare pass marks in both exams, but one answers only the even questions and only answers the odd. (And, yes, there are an even number of questions.) Because of the way the assessment was constructed, they have managed to avoid any common answers in the same area of course knowledge. Yet, both end up scoring 50%, a passing grade in the Australian system.

Which of these students has the correct half of the knowledge?

I had planned to build up to Rapaport but, if you’re reading the blog comments, he’s already been mentioned so I’ll summarise his 2011 paper before I get to my main point. In 2011, William J. Rapaport, SUNY Buffalo, published a paper entitled “A Triage Theory of Grading: The Good, The Bad and the Middling.” in Teaching Philosophy. This paper summarised a number of thoughtful and important authors, among them Perry, Wolff, and Kohn. Rapaport starts by asking why we grade, moving through Wolff’s taxonomic classification of assessment into criticism, evaluation, and ranking. Students are trained, by our world and our education systems to treat grades as a measure of progress and, in many ways, a proxy for knowledge. But this brings us into conflict with Perry’s developmental stages, where students start with a deep need for authority and the safety of a single right answer. It is only when students are capable of understanding that there are, in many cases, multiple right answers that we can expect them to understand that grades can have multiple meanings. As Rapaport notes, grades are inherently dual: a representative symbol attached to a quality measure and then, in his words, “ethical and aesthetic values are attached” (emphasis mine.) In other words, a B is a measure of progress (not quite there) that also has a value of being … second-tier if an A is our measure of excellence. A is not A, as it must be contextualised. Sorry, Ayn.

When we start to examine why we are grading, Kohn tells us that the carrot and stick is never as effective as the motivation that someone has intrinsically. So we look to Wolff: are we critiquing for feedback, are we evaluating learning, or are we providing handy value measures for sorting our product for some consumer or market? Returning to my thought experiment above, we cannot provide feedback on assignments that students don’t do, our evaluation of learning says that both students are acceptable for complementary knowledge, and our students cannot be discerned from their graded rank, despite the fact that they have nothing in common!

Yes, it’s an artificial example but, without attention to the design of our courses and in particular the design of our assessment, it is entirely possible to achieve this result to some degree. This is where I wish to refer to Rapaport as an example of thoughtful design, with a clear assessment goal in mind. To step away from measures that provide an (effectively) arbitrary distinction, Rapaport proposes a tiered system for grading that simplifies the overall system with an emphasis on identifying whether a piece of assessment work is demonstrating clear knowledge, a partial solution, an incorrect solution or no work at all.

This, for me, is an example of assessment that is pretty close to true. The difference between a 74 and a 75 is, in most cases, not very defensible (after Haladyna) unless you are applying some kind of ‘quality gate’ that really reduces a percentile scale to, at most, 13 different outcomes. Rapaport’s argument is that we can reduce this further and this will reduce grade clawing, identify clear levels of achieve and reduce marking load on the assessor. That last point is important. A system that buries the marker under load is not sustainable. It cannot be beautiful.

There are issues in taking this approach and turning it back into the grades that our institutions generally require. Rapaport is very open about the difficulties that he has turning his triage system into an acceptable letter grade and it’s worth reading the paper to see that discussion alone, because it quite clearly shows what

Rapaport’s scheme clearly defines which of Wolff’s criteria he wishes his assessment to achieve. The scheme, for individual assessments, is no good for ranking (although we can fashion a ranking from it) but it is good to identify weak areas of knowledge (as transmitted or received) for evaluation of progress and also for providing elementary critique. It says what it is and it pretty much does it. It sets out to achieve a clear goal.

The paper ends with a summary of the key points of Haladyna’s 1999 book “A Complete Guide to Student Grading”, which brings all of this together.

Haladyna says that “Before we assign a grade to any students, we need:

- an idea about what a grade means,

- an understanding of the purposes of grading,

- a set of personal beliefs and proven principles that we will use in teaching

and grading,

- a set of criteria on which the grade is based, and, finally,

- a grading method,which is a set of procedures that we consistently follow

in arriving at each student’s grade. (Haladyna 1999: ix)

There is no doubt that Rapaport’s scheme meets all of these criteria and, yet, for me, we have not yet gone far enough in search of the most beautiful, most good and most true extent that we can take this idea. Is point 3, which could be summarised as aesthetics not enough for me? Apparently not.

Tomorrow I will return to Rapaport to discuss those aspects I disagree with and, later on, discuss both an even more trimmed-down model and some more controversial aspects.

A Year of Beauty

Posted: January 1, 2016 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, beauty, blogging, design, education, educational problem, educational research, good, higher education, plato, principles of design, reflection, socrates, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, truth, vygotsky, workload 5 Comments

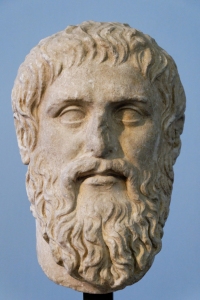

Plato: Unifying key cosmic values of Greek culture to a useful conceptual trinity.

Ever since education became something we discussed, teachers and learners alike have had strong opinions regarding the quality of education and how it can be improved. What is surprising, as you look at these discussions over time, is how often we seem to come back to the same ideas. We read Dewey and we hear echoes of Rousseau. So many echoes and so much careful thought, found as we built new modern frames with Vygotsky, Piaget, Montessori, Papert and so many more. But little of this should really be a surprise because we can go back to the writings of Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (Quinitilian) and his twelve books of The Orator’s Education and we find discussion of small class sizes, constructive student-focused discussions, and that more people were capable of thought and far-reaching intellectual pursuits than was popularly believed.

“… as birds are born for flying, horses for speed, beasts of prey for ferocity, so are [humans] for mental activity and resourcefulness.” Quintilian, Book I, page 65.

I used to say that it was stunning how contemporary education seems to be slow in moving in directions first suggested by Dewey a hundred years ago, then I discovered that Rousseau had said it 150 years before that. Now I find that Quntilian wrote things such as this nearly 2,000 years ago. And Marcus Aurelius, among other stoics, made much of approaches to thinking that, somehow, were put to one side as we industrialised education much as we had industrialised everything else.

This year I have accepted that we have had 2,000 years of thinking (and as much evidence when we are bold enough to experiment) and yet we just have not seen enough change. Dewey’s critique of the University is still valid. Rousseau’s lament on attaining true mastery of knowledge stands. Quintilian’s distrust of mere imitation would not be quieted when looking at much of repetitive modern examination practice.

What stops us from changing? We have more than enough evidence of discussion and thought, from some of the greatest philosophers we have seen. When we start looking at education, in varying forms, we wander across Plato, Hypatia, Hegel, Kant, Nietzsche, in addition to all of those I have already mentioned. But evidence, as it stands, does not appear to be enough, especially in the face of personal perception of achievement, contribution and outcomes, whether supported by facts or not.

Evidence of uncertainty is not enough. Evidence of the lack of efficacy of techniques, now that we can and do measure them, is not enough. Evidence that students fail who then, under other tutors or approaches, mysteriously flourish elsewhere, is not enough.

Authority, by itself, is not enough. We can be told to do more or to do things differently but the research we have suggests that an externally applied control mechanism just doesn’t work very well for areas where thinking is required. And thinking is, most definitely, required for education.

I have already commented elsewhere on Mark Guzdial’s post that attracted so much attention and, yet, all he was saying was what we have seen repeated throughout history and is now supported in this ‘gilt age’ of measurement of efficacy. It still took local authority to stop people piling onto him (even under the rather shabby cloak of ‘scientific enquiry’ that masks so much negative activity). Mark is repeating the words of educators throughout the ages who have stepped back and asked “Is what we are doing the best thing we could be doing?” It is human to say “But, if I know that this is the evidence, why am I acting as if it were not true?” But it is quite clear that this is still challenging and, amazingly, heretical to an extent, despite these (apparently controversial) ideas pre-dating most of what we know as the trappings and establishments of education. Here is our evidence that evidence is not enough. This experience is the authority that, while authority can halt a debate, authority cannot force people to alter such a deeply complex and cognitive practice in a useful manner. Nobody is necessarily agreeing with Mark, they’re just no longer arguing. That’s not helpful.

So, where to from here?

We should not throw out everything old simply because it is old, as that is meaningless without evidence to do so and it is wrong as autocratically rejecting everything new because it is new.

The challenge is to find a way of explaining how things could change without forcing conflict between evidence and personal experience and without having to resort to an argument by authority, whether moral or experiential. And this is a massive challenge.

This year, I looked back to find other ways forward. I looked back to the three values of Ancient Greece, brought together as a trinity through Socrates and Plato.

These three values are: beauty, goodness and truth. Here, truth means seeing things as they are (non-concealment). Goodness denotes the excellence of something and often refers to a purpose of meaning for existence, in the sense of a good life. Beauty? Beauty is an aesthetic delight; pleasing to those senses that value certain criteria. It does not merely mean pretty, as we can have many ways that something is aesthetically pleasing. For Dewey, equality of access was an essential criterion of education; education could only be beautiful to Dewey if it was free and easily available. For Plato, the revelation of knowledge was good and beauty could arose a love for this knowledge that would lead to such a good. By revealing good, reality, to our selves and our world, we are ultimately seeking truth: seeing the world as it really is.

In the Platonic ideal, a beautiful education leads us to fall in love with learning and gives us momentum to strive for good, which will lead us to truth. Is there any better expression of what we all would really want to see in our classrooms?

I can speak of efficiencies of education, of retention rates and average grades. Or I can ask you if something is beautiful. We may not all agree on details of constructivist theory but if we can discuss those characteristics that we can maximise to lead towards a beautiful outcome, aesthetics, perhaps we can understand where we differ and, even more optimistically, move towards agreement. Towards beautiful educational practice. Towards a system and methodology that makes our students as excited about learning as we are about teaching. Let me illustrate.

A teacher stands in front of a class, delivering the same lecture that has been delivered for the last ten years. From the same book. The classroom is half-empty. There’s an assignment due tomorrow morning. Same assignment as the last three years. The teacher knows roughly how many people will ask for an extension an hour beforehand, how many will hand up and how many will cheat.

I can talk about evidence, about pedagogy, about political and class theory, about all forms of authority, or I can ask you, in the privacy of your head, to think about these questions.

- Is this beautiful? Which of the aesthetics of education are really being satisfied here?

- Is it good? Is this going to lead to the outcomes that you want for all of the students in the class?

- Is it true? Is this really the way that your students will be applying this knowledge, developing it, exploring it and taking it further, to hand on to other people?

- And now, having thought about yourself, what do you think your students would say? Would they think this was beautiful, once you explained what you meant?

Over the coming year, I will be writing a lot more on this. I know that this idea is not unique (Dewey wrote on this, to an extent, and, more recently, several books in the dramatic arts have taken up the case of beauty and education) but it is one that we do not often address in science and engineering.

My challenge, for 2016, is to try to provide a year of beautiful education. Succeed or fail, I will document it here.

Why writing 50,000 words doesn’t matter as much as writing one.

Posted: October 26, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: blogging, community, education, educational research, goals, higher education, NaNoWriMo, thinking, tools, workload, writing 3 CommentsHave you heard of NaNoWriMo? National Novel Writing Month has been around since 1999 and is now far more widespread than national boundaries and has become relatively large, with 325,142 participants on six continents in 2014. The idea is simple: over the 30 days of November, you write 50,000 words that are (notionally) all directed towards a fictional novel.

I’ve taken part twice in the past and produced two … rapidly written works of fiction. I have never claimed to be a good writer, I’m certainly not a published writer, but I can put a number of words down on the page in a day. They even make sense, most of the time, and I’ve ended up with stories that real people have actually read and enjoyed!

I like NaNoWriMo. I like it as a concept, because it demystifies the concept of writing that many words by saying “Hey! Don’t get caught up on perfect prose, just start by writing.” I like the community because, despite the large number of people who show up and have no intention of doing it, there are enough like minds to give you support when you need it. I like it personally, as it’s a great way to get down a long draft of a work, even if you don’t do anything else with it. It’s a bit of external structure (and scaffolding) for those of us who aren’t professional authors.

Being me, of course, I’m all about seeing if we can get people doing something that they didn’t think possible, so I look at NaNoWriMo as a success for anyone who writes one more word than they otherwise would have in November. Sure, getting down a whole novel would be awesome but any steps forward are good steps.

We could talk a lot about how this kind of constrained activity can work in a creative setting but, if you know my work, you’ll have a fairly good idea that I think that everyone taking part should have “enjoyment” as their primary goal, with a possible outcome of their first long-form work as a happy side-effect. 50K shouldn’t be a burden but a guide. 1,700 words a day can be more manageable than many people think and, at the end of November, you may have done something you never thought possible.

Whatever happens, you’ll be thinking creatively and that, in my book, is always awesome. “Almighty creativity”, as the late Bob Ross might say.

I’ll be doing NaNo again this year and, if you’re thinking about it, check out the web site or my shortish guide to speed writing (AntifreezePub) that I’ve written based on my own experiences over the years. As always, if you think there should be a better speed writing guide, feel free to write it/find it and link to it in the comments!

I decided to have an outrageous book cover to inspire me and get me into the right mood. (Currently a working copy with placeholder artwork, as I have no idea what will make it into the final draft.)

Almost all of us benefit from writing practice and this is an interesting way to get a lot of practice in a short time. If you do it, have fun, and feel free to buddy up with me under the username jnick.

Promoting acceptance by understanding people.

Posted: June 28, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: academic publishing, advocacy, authenticity, blogging, education, feedback, fiction, Matthew Effect, publishing, scientific publishing, thinking, universal principles of design, workload, writing 4 CommentsLet me start by putting up a picture of some people celebrating!

My first confession is that the ‘acceptance’ I’m talking about is for academic and traditional fiction publishing. The second confession is that I have attempted to manipulate you into clicking through by using a carefully chosen title and presented image. This is to lead off with the point I wish to make today: we are a mess of implicit and explicit cognitive biases and to assume that we have anything approximating a fair evaluation mechanism to get work published is to, sadly, be making a far reaching assumption.

If you’ve read this far, my simple takeaway is “If people don’t even start reading your work with a positive frame of mind and a full stomach, your chances of being accepted are dire.”

If you want to hang around my argument is going to be simple. I’m going to demonstrate that, for much simpler assessments than research papers or stories, simple cognitive biases have a strong effect. I’m going to follow this and indicate how something as simple as how hungry you are can affect your decision making. I’m then going to identify a difference between scientific publishing and non-scientific publishing in terms of feedback and why expecting that we will continue to get good results from both approaches is probably too optimistic. I am going to make some proposals as to how we might start thinking about a fix, but only to start discussion because my expertise in non-academic publishing is not all that deep and limited by not being an editor or publisher!

[Full disclosure: I am happily published in academia but I am yet to be accepted for publication in non-academic approaches. I am perfectly comfortable with this so please don’t read sour grapes into this argument. As you’ll see, with the approaches I propose, I would in fact strip myself of some potential bias privileges!]

I’ve posted before on an experiment [1] where the only change to the qualifications of a prospective lab manager was to take the name from male to female. The ‘female’ version of this CV got offered less money, less development support and was ‘obviously’ less qualified. And this effect occurred whether the assessor was a man or a woman. This is the pretty much the gold standard for experiments of this type because it reduced any possibility of someone acting out of character because they knew what the experiment was trying to prove. There’s a lot of discussion in fiction at the moment about gendered bias, as well as academia. You’re probably aware of the Bechdel Test, which simply asks if there are two named women in a film who talk to each other about something other than men, and how often the mainstream media fails that test. But let’s look at something else. Antony LaPaglia tells a story that he used to get pulled up on his American accent whenever anyone knew that he was Australian. So he started passing as American. Overnight, complaints about his accent went away.

Compared to assessing a manuscript, reading a CV, bothering to put in two woman with names and a story, and spotting an accent are trivial and yet we can’t get these right without bias.

There’s another thing called the Matthew Effect, which basically says that the more you have, the more you’re going to get (terrible paraphrasing). Thus, the first paper in a field will be one of the most cited, people are comfortable giving opportunities to people who have used them well before, and so on. It even shows up in graph theory, where the first group of things connected together tend to become the most connected!

So, we have lots of examples of bias that comes in, if we know enough about someone that the bias can engage. And, for most people who aren’t trying to be discriminatory, it’s actually completely unconscious. Really? You don’t think you’d notice?

Let’s look at the hunger argument. An incredible study [2] (Economist link for summary) shows that Israeli judges are less likely to grant parole, the longer they’ve waited since they ate, even when taking other factors into account. Here’s a graph. Those big dips are meal breaks.

When confronted with that terrifying graph, the judges were totally unaware of it. The people in the court every day hadn’t noticed it. The authors of the study looked at a large number of factors and found some things that you’d expect in terms of sentencing but the meal break plunges surprised everyone because they had never thought to look for it. The good news is that, most days, the most deserving will still get paroled but, and it’s a big but, you still have to wonder about the people who should have been given parole who were denied because of timing and also the people who were paroled who maybe should not have been.

So what distinguishes academia and non-academic publishing? Shall we start by saying that, notionally, many parts of academic publishing subscribe to the Popperian model of development where we expose ideas to our colleagues and they tear at them like deranged wolves until we fashion truth? As part of that, we expect to get reviews from almost all submissions, whether accepted or not, because that is how we build up academic consensus and find out new things. Actual publication allows you to put your work out to everyone else where they can read it, work with it or use it to fashion a counter-claim.

In non-academic publishing, the publisher wants something that is saleable in the target market and the author wants to provide this. The author probably also wants to make some very important statements about truth, beauty, the lizard people or anything else (much as in academic publishing, the spread of ideas is crucial). However, from a publisher’s perspective, they are not after peer-verified work of sufficient truth, they are after something that matches their needs in order to publish it, most likely for profit.

Both are directly or indirectly prestige markers and often have some form of financial rewards, as well as some truth/knowledge construction function. Non-academic authors publish to eat, academic authors publish to keep their jobs or get tenure (often enough to allow you to eat). But the key difference is the way that feedback is given because an academic journal that gave no feedback would have trouble staying in business (unless it had incredible acceptance already, see Matthew Effect) because we’re all notionally building knowledge. But “no feedback” is the default in other publishing.

When I get feedback academically, I can quickly work out several things:

- Is the reviewer actually qualified to review my work? If someone doesn’t have the right background, they start saying things like surely when they mean I don’t know, and it quickly tells you that this review will be uninformative.

- Has the reviewer actually read the work? I would ask all the academics reading this to send me $1 if they’ve ever been told to include something that is obviously in the paper and takes up 1-2 pages already, except I am scared of the tax and weight implications.

- How the feedback can be useful. Good feedback is great. It spots holes, it reinforces bridges, it suggests new directions.

- If I want to publish in that venue again. If someone can’t organise their reviewers and oversee the reviews properly? I’m not going to get what I need to do good work. I should go and publish elsewhere.

My current exposure to non-academic publishing has been: submit story, wait, get rejection. Feedback? “Not suitable for us but thank you for your interest”, “not quite right for us”,”I’m going to pass on this”. I should note that the editors have all been very nice, timely (scarily so, in some cases) and all of my interactions have been great – my problem is mechanistic, not personal. I should clearly state that I assume that point 1 from above holds for all non-academic publishing, that is that the editors have chosen someone to review in a genre that they don’t actually hate and know something about. So 1 is fine. But 2 is tricky when you get no feedback.

But that tricky #2, “Has the reviewer actually read the work”, in the context of my previous statements really becomes “HOW has the reviewer read my work?” Is there an informal ordering of people you think you’ll enjoy to newbies, even unconsciously? How hungry is the reviewer when they’re working? Do they clear up ‘simple checks’ just before lunch? In the absence of feedback, I can’t assess the validity of the mechanism. I can’t improve the work with no feedback (step 3) and I’m now torn as to whether this story was bad for a given venue or whether my writing is just so awful that I should never darken their door again! (I accept, dear reader, that this may just be the sad truth and they’re all too scared to tell me.)

Let me remind you that implicit bias is often completely unconscious and many people are deeply surprised when they discover what they have been doing. I imagine that there are a number of reviewers reading this who are quite insulted. I certainly don’t mean to offend but I will ask if you’ve sat down and collected data on your practice. If you have, I would really love to see it because I love data! But, if what you have is your memory of trying to be fair… Many people will be in denial because we all like to think we’re rational and fair decision makers. (Looks back at those studies. Umm.)

We can deal with some aspects of implicit bias by using blind review systems, where the reviewer only sees the work and we remove any clues as to who wrote it. In academia this can get hard because some people’s contributed signature is so easy to see but it is still widely used. (I imagine it’s equally hard for well known writers.) This will, at least, remove gender bias and potentially reduce the impact of “famous people”, unless they are really distinctive. I know that a blinding process isn’t happening in all of the parts of non-academic publishing because my name is all over my manuscripts. (I must note that there are places that use blind submission, such as Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine and Aurealis, for initial reading, which is a great start.) Usually, when I submit, my covering letter has to clearly state my publication history. This is the very opposite of a blind process because I am being asked to rate myself for Matthew Effect scaling every time I submit!

(There are also some tips and tricks in fiction, where your rejections can be personalised, yet contain no improvement information. This is still “a better rejection” but you have to know this from elsewhere because it’s not obvious. Knowing better writers is generally the best way to get to know about this. Transparency is not high, here.)

The timing one is harder because it requires two things: multiple reviewers and a randomised reading schedule, neither of which take into account the shoe string budgets and volunteer workforce associated with much of fiction publishing. Ideally, an anonymised work gets read 2-3 times, at different times relative to meals and during the day, taking into account the schedule of the reader. Otherwise, that last manuscript you reject before rushing home at 10pm to reheat a stale bagel? It would have to be Hemingway to get accepted. And good Hemingway at that.

And I’d like to see randomised reading applied across academic publishing as well. And we keep reviewing it until we actually reach a consensus. I’ve been on a review panel recently where we had two ‘accepts’, two ‘mehs’ and two ‘kill it with fires’ for the same paper. After group discussion, we settled for ‘a weak accept/strong meh’. Why? Because the two people who had rated it right down weren’t really experts so didn’t recognise what was going on. Why were they reviewing? Because it’s part of the job. So don’t think I’m going after non-academic publishing here. I’m exposing problems in both because I want to try and fix both.

But I do recognise that the primary job of non-academic publishing is getting people to read the publication, which means targeting saleable works. Can we do this in a way that is more systematic than “I know good writing when I see it” because (a) that doesn’t scale and (b) the chances of that aligning across more than two people is tiny.

This is where technological support can be invaluable. Word counting, spell checking and primitive grammar checking are all the dominion of the machine, as is plagiarism detection on existing published works. So step one is a brick wall that says “This work has not been checked against our submissions standards: problems are…” and this need not involve a single human (unless you are trying to spellcheck The Shugenkraft of Berzxx, in which case have a tickbox for ‘Heavy use of neologisms and accents’.) Plagiarism detection is becoming more common in academic writing and it saves a lot of time because you don’t spend it reading lifted work. (I read something that was really familiar and realised someone had sent me some of my own work with their name on it. Just… no.)

What we want is to go from a flood, to a river, then to manage that river and direct it to people who can handle a stream at a time. Human beings should not be the cogs and failure points in the high volume non-academic publishing industry.

Stripping names, anonymising and randomly distributing work is fairly important if we want to remove time biases. Even the act of blinding and randomising is going to reduce the chances that the same people get the same good or bad slots. We are partially systematic. Almost everyone in the industry is overworked, doing vast and wonderful things and, in the face of that, tired and biassed behaviour becomes more likely.

The final thing that would be useful is something alone the lines of a floating set of check boxes that sit with the document, if it’s electronic. (On paper, have a separate sheet that you can scan in once it’s filled in and then automatically extract the info.) What do you actually expect? What is this work/story not giving you? Is it derivative work? Is it just all talk and no action? Is it too early and just doesn’t go anywhere? Separating documents from any form of feedback automation (or expecting people to type sentences) is going to slow things down and make it impossible to give feedback. Every publishing house has a list of things not to do, let’s start with the 10 worst of those and see how many more we can get onto the feedback screen.

I am thinking of an approach that makes feedback an associated act of reading and can then be sent, with accept or reject, in the same action. Perhaps it has already been created and is in use in fine publishing houses, but my work hasn’t hit a bar where I even get that feedback? I don’t know. I can see that distributed editorial boards, like Andromeda, are obviously taking steps down this path because they have had to get good at shunting stuff around at scale and I would love to know how far they’ve got. For me, a mag that said “We will always give you even a little bit of feedback” will probably get all of my stuff first. (Not that they want it but you get the idea.)

I understand completely that publishers are under no obligation whatsoever to do this. There is no right to feedback nor is there an expectation outside of academia. But if we want good work, then I think I’ve already shown that we are probably missing out on some of it and, by not providing feedback, some (if not many) of those stories will vanish, never worked on again, never seen again, because the authors have absolutely no guidance on how to change their work.

I have already discussed mocking up a system, building from digital humanist approaches and using our own expertise, with one of my colleagues and we hope to start working on something soon. But I’d rather build something that works for everyone and lets publishers get more good work, authors recognised when they get it right, and something that brings more and more new voices into the community. Let me know if it’s already been written or take me to school in the comments below. I can’t complain about lack of feedback and then ignore it when I get it!

[1] PNAS, vol. 109 no. 41, Corinne A. Moss-Racusin, 16474–16479, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211286109

[2] PNAS vol. 108 no. 17, Shai Danziger, 6889–6892, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018033108

EduTech AU 2015, Day 2, Higher Ed Leaders, “Assessment: The Silent Killer of Learning”, #edutechau @eric_mazur

Posted: June 3, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: assessment, educational problem, educational research, edutech2015, edutechau, eric mazur, feedback, harvard, higher education, in the student's head, learning, peer instruction, plagiarism, student perspective, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, tools, universal principles of design, workload 3 CommentsNo surprise that I’m very excited about this talk as well. Eric is a world renowned educator and physicist, having developed Peer Instruction in 1990 for his classes at Harvard as a way to deal with students not developing a working physicist’s approach to the content of his course. I should note that Eric also gave this talk yesterday and the inimitable Steve Wheeler blogged that one, so you should read Steve as well. But after me. (Sorry, Steve.)

I’m not an enormous fan of most of the assessment we use as most grades are meaningless, assessment becomes part of a carrot-and-stick approach and it’s all based on artificial timelines that stifle creativity. (But apart from that, it’s fine. Ho ho.) My pithy statement on this is that if you build an adversarial educational system, you’ll get adversaries, but if you bother to build a learning environment, you’ll get learning. One of the natural outcomes of an adversarial system is activities like cheating and gaming the system, because people start to treat beating the system as the goal itself, which is highly undesirable. You can read a lot more about my views on plagiarism here, if you like. (Warning: that post links to several others and is a bit of a wormhole.)

Now, let’s hear what Eric has to say on this! (My comments from this point on will attempt to contain themselves in parentheses. You can find the slides for his talk – all 62MB of them – from this link on his website. ) It’s important to remember that one of the reasons that Eric’s work is so interesting is that he is looking for evidence-based approaches to education.

Eric discussed the use of flashcards. A week after Flashcard study, students retain 35%. After two weeks, it’s almost gone. He tried to communicate this to someone who was launching a cloud-based flashcard app. Her response was “we only guarantee they’ll pass the test”.

*low, despairing chuckle from the audience*

Of course most students study to pass the test, not to learn, and they are not the same thing. For years, Eric has been bashing the lecture (yes, he noted the irony) but now he wants to focus on changing assessment and getting it away from rote learning and regurgitation. The assessment practices we use now are not 21st century focused, they are used for ranking and classifying but, even then, doing it badly.

So why are we assessing? What are the problems that are rampant in our assessment procedure? What are the improvements we can make?

How many different purposes of assessment can you think of? Eric gave us 90s to come up with a list. Katrina and I came up with about 10, most of which were serious, but it was an interesting question to reflect upon. (Eric snuck

- Rate and rank students

- Rate professor and course

- Motivate students to keep up with work

- Provide feedback on learning to students

- Provide feedback to instructor

- Provide instructional accountability

- Improve the teaching and learning.

Ah, but look at the verbs – they are multi-purpose and in conflict. How can one thing do so much?

So what are the problems? Many tests are fundamentally inauthentic – regurgitation in useless and inappropriate ways. Many problem-solving approaches are inauthentic as well (a big problem for computing, we keep writing “Hello, World”). What does a real problem look like? It’s an interruption in our pathway to our desired outcome – it’s not the outcome that’s important, it’s the pathway and the solution to reach it that are important. Typical student problem? Open the book to chapter X to apply known procedure Y to determine an unknown answer.

Shout out to Bloom’s! Here’s Eric’s slide to remind you.

Eric doesn’t think that many of us, including Harvard, even reach the Applying stage. He referred to a colleague in physics who used baseball problems throughout the course in assignments, until he reached the final exam where he ran out of baseball problems and used football problems. “Professor! We’ve never done football problems!” Eric noted that, while the audience were laughing, we should really be crying. If we can’t apply what we’ve learned then we haven’t actually learned i.

Eric sneakily put more audience participation into the talk with an open ended question that appeared to not have enough information to come up with a solution, as it required assumptions and modelling. From a Bloom’s perspective, this is right up the top.

Students loathe assumptions? Why? Mostly because we’ll give them bad marks if they get it wrong. But isn’t the ability to make assumptions a really important skill? Isn’t this fundamental to success?

Eric demonstrated how to tame the problem by adding in more constraints but this came at the cost of the creating stage of Bloom’s and then the evaluating and analysing. (Check out his slides, pages 31 to 40, for details of this.) If you add in the memorisation of the equation, we have taken all of the guts out of the problem, dropping down to the lowest level of Bloom’s.

But, of course, computers can do most of the hard work for that is mechanistic. Problems at the bottom layer of Bloom’s are going to be solved by machines – this is not something we should train 21st Century students for.

But… real problem solving is erratic. Riddled with fuzziness. Failure prone. Not guaranteed to succeed. Most definitely not guaranteed to be optimal. The road to success is littered with failures.

But, if you make mistakes, you lose marks. But if you’re not making mistakes, you’re very unlikely to be creative and innovative and this is the problem with our assessment practices.

Eric showed us a stress of a traditional exam room: stressful, isolated, deprived of calculators and devices. Eric’s joke was that we are going to have to take exams naked to ensure we’re not wearing smart devices. We are in a time and place where we can look up whatever we want, whenever we want. But it’s how you use that information that makes a difference. Why are we testing and assessing students under such a set of conditions? Why do we imagine that the result we get here is going to be any indicator at all of the likely future success of the student with that knowledge?

Cramming for exams? Great, we store the information in short-term memory. A few days later, it’s all gone.

Assessment produces a conflict, which Eric noticed when he started teaching a team and project based course. He was coaching for most of the course, switching to a judging role for the monthly fair. He found it difficult to judge them because he had a coach/judge conflict. Why do we combine it in education when it would be unfair or unpleasant in every other area of human endeavour? We hide between the veil of objectivity and fairness. It’s not a matter of feelings.

But… we go back to Bloom’s. The only thinking skill that can be evaluated truly objectively is remembering, at the bottom again.

But let’s talk about grade inflation and cheating. Why do people cheat at education when they don’t generally cheat at learning? But educational systems often conspire to rob us of our ownership and love of learning. Our systems set up situations where students cheat in order to succeed.

- Mimic real life in assessment practices!

Open-book exams. Information sticks when you need it and use it a lot. So use it. Produce problems that need it. Eric’s thought is you can bring anything you want except for another living person. But what about assessment on laptops? Oh no, Google access! But is that actually a problem? Any question to which the answer can be Googled is not an authentic question to determine learning!

Eric showed a video of excited students doing a statistic tests as a team-based learning activity. After an initial pass at the test, the individual response is collected (for up to 50% of the grade), and then students work as a group to confirm the questions against an IF AT scratchy card for the rest of the marks. Discussion, conversation, and the students do their own grading for you. They’ve also had the “A-ha!” moment. Assessment becomes a learning opportunity.

Eric’s not a fan of multiple choice so his Learning Catalytics software allows similar comparison of group answers without having to use multiple choice. Again, the team based activities are social, interactive and must less stressful.

- Focus on feedback, not ranking.

Objective ranking is a myth. The amount of, and success with, advanced education is no indicator of overall success in many regards. So why do we rank? Eric showed some graphs of his students (in earlier courses) plotting final grades in physics against the conceptual understanding of force. Some people still got top grades without understanding force as it was redefined by Newton. (For those who don’t know, Aristotle was wrong on this one.) Worse still is the student who mastered the concept of force and got a C, when a student who didn’t master force got an A. Objectivity? Injustice?

- Focus on skills, not content

Eric referred to Wiggins and McTighe, “Understanding by Design.” Traditional approach is course content drives assessment design. Wiggins advocates identifying what the outcomes are, formulate these as action verbs, ‘doing’ x rather than ‘understanding’ x. You use this to identify what you think the acceptable evidence is for these outcomes and then you develop the instructional approach. This is totally outcomes based.

- resolve coach/judge conflict

In his project-based course, Eric brought in external evaluators, leaving his coach role unsullied. This also validates Eric’s approach in the eyes of his colleagues. Peer- and self-evaluation are also crucial here. Reflective time to work out how you are going is easier if you can see other people’s work (even anonymously). Calibrated peer review, cpr.molsci.ucla.edu, is another approach but Eric ran out of time on this one.

If we don’t rethink assessment, the result of our assessment procedures will never actually provide vital information to the learner or us as to who might or might not be successful.

I really enjoyed this talk. I agree with just about all of this. It’s always good when an ‘internationally respected educator’ says it as then I can quote him and get traction in change-driving arguments back home. Thanks for a great talk!

EduTech Australia 2015, Day 1, Session 1, Higher Education Leaders @jselingo #edutechau

Posted: June 2, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, blogging, education, educational research, edutech2015, edutechau, higher education, Jeffrey Selingo, learning, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, workload Leave a commentEmeritus Professor Steven Schwartz, AM, opened the Higher Ed leaders session, following a very punchy video on how digital is doing “zoom” and “rock and roll” things. (I’m a bit jaded about “tech wow” videos but this one was pretty good. It reinforced the fact that over 60% of all web browsing is carried out on mobile devices, which should be a nudge to all of us designing for the web.)

There will be roughly 5,000 participants in the totally monstrous Brisbane Convention Centre. There are many people here that I know but I’m beginning to doubt whether I’m going to see many of them unless they’re speaking – there’s a mass of educational humanity here, people!

The opening talk was “The Universities of tomorrow, the future of anytime and anywhere learning”, presented by Jeffrey Selingo. Jeff writes books, “College Unbound” among others, and is regular contributor to the Washington Post and the Chronicle. (I live for the day I can put “Education Visionary” on my slides with even a shred of this credibility. As a note, remarks in parentheses are probably my editorial comments.)

(I’ve linked to Jeff on Twitter. Please correct me on anything, Jeff!)

Jeff sought out to explore the future of higher learning, taking time out from editing the Chronicle. He wanted to tell the story of higher ed for the coming decade, for those parents and students heading towards it now, rather than being in it now. Jeff approached it as a report, rather than an academic paper, and is very open about the fact that he’s not conducting research. “In journalism, if you have three anecdotes, you have a trend.”

(I’m tempted to claim phenomenography but I know you’ll howl me down. And rightly so!)

Higher Ed is something that, now, you encounter once in our lives and then move on. But the growth in knowledge and ongoing explosion of new information doesn’t match that model. Our Higher Ed model is based on an older tradition and and older informational model.

(This is great news for me, I’m a strong advocate of an integrated and lifelong Higher Ed experience)

(Slides for this talk available at http://jeffselingo.com/conference

Be warned, you have to sign up for a newsletter to get the slides.)

Jeff then talked about his start, in one of the initial US college rankings, before we all ranked each other into the ground. The ‘prestige race’ as he refers to it. Every university around the world wanted to move up the ladder. (Except for the ones on the top, kicking at the rungs below, no doubt.)

“Prestige is to higher education as profit is to corporations.”

According to Caroline Hoxby, Higher Ed student flow has increased as students move around the world. Students who can move to different Universities, now tend to do so and they can exercise choices around the world. This leads to predictions like “the bottom 25% of Unis will go out of business or merge” (Clay Christensen) – Jeff disagrees with this although he thinks change is inevitable.

We have a model of new, technologically innovative and agile companies destroy the old leaders. Netflix ate Blockbuster. Amazon ate Borders. Apple ate… well, everybody… but let’s say Tower Records, shall we? Jeff noted that journalism’s upheaval has been phenomenal, despite the view of journalism as a ‘public trust’. People didn’t want to believe what was going to happen to their industry.

Jeff believes that students are going to drive the change. He believes that students are often labelled as “Traditional” (ex-school, 18-22, direct entry) and “non-Traditional” (adult learners, didn’t enter directly.) But what this doesn’t capture is the mindset or motivation of students to go to college. (MOOC motivation issues, anyone?)

What do students want to get out of their degree?

(Don’t ask difficult questions like that, Jeff! It is, of course, a great question and one we try to ask but I’m not sure we always listen.)

Why are you going? What do you want? What do you want your degree to look like? Jeff asked and got six ‘buckets’ of students in two groups, split across the trad/non-trad age groups.

Group 1 are the younger group and they break down into.

- Young Academics (24%) – the trad high-performing students who have mastered the earlier education systems and usually have a privileged background

- Coming of Age (11%) – Don’t quite know what they want from Uni but they were going to college because it was the place to go to become an adult. This is getting them ready to go to the next step, the work force.

- Career Starters (18%) – Students who see the Uni as a means to the end, credentialing for the job that they want. Get through Uni as quickly as possible.

Group 2 are older:

- Career Accelerators (21%) – Older students who are looking to get new credentials to advance themselves in their current field.

- Industry Switchers – Credential changers to move to a new industry.

- Adult Wanderers – needed a degree because that was what the market told them but they weren’t sure why

(Apologies for losing some of the stats, the room’s quite full and some people had to walk past me.)

But that’s what students are doing – what skills are required out there from the employers?

- Written and Oral communication

- Managing multiple priorities

- Collaboration

- Problem solving

People used to go to college for a broad knowledge base and then have that honed by an employer or graduate school to focus them into a discipline. Now, both of these are expected at the Undergrad level, which is fascinating given that we don’t have extra years to add to the degree. But we’re not preparing students better to enter college, nor do we have the space for experiential learning.

Expectations are greater than ever but are we delivering?

When do we need higher education? Well, it used to be “education” then “employment” then “retirement”. The new model, today, (from Georgetown, Tony Carnevale), we have “education”, then “learning and earning”, then “full-time work and on-the-job training”, “transition to retirement” and, finally, “full retirement”. Students are finally focusing on their career at around 30, after leaving the previous learning phases. This is, Jeff believes, where we are not playing an important role for students in their 20s, which is not helping them in their failure to launch.

Jeff was wondering how different life would be for the future, especially given how much longer we are going to be living. How does that Uni experience of “once in our lives, in one physical place” fit in, if people may switch jobs much more frequently over a longer life? The average person apparently switches jobs every four years – no wonder most of the software systems I use are so bad!

Je”s “College Unbound” future is student-driven, student-centred, and not a box that is entered at 18 and existed 4 years later, it’s a platform for life-long learning.

“The illiterate will be those who cannot learn, unlearn and relearn” – Alvin Toffler

Jeff doesn’t think that there will be one simple path to the future. Our single playing field competition of institutions has made us highly similar in the higher ed sector. How can we personalise pathways to the different groups of students that we saw above? Predictive analytics are important here – technology is vital. Good future education will be adaptive and experiential, combining the trad classroom with online systems. apprenticeships and, overall, removing the requirement to reside at or near your college.

Jeff talked about some new models, starting with the Swirl, the unbundled degree across different institutions, traditional snd not. Multiple universities, multiple experiences = degree.

Then there’s mixing course types, mixing face-to-face with hybrid and online to accelerate their speed of graduation. (There is a strong philosophical point on this that I hope to get back to later: why are we racing through University?)

Finally, competency-based learning allowed a learner to have class lengths from 2 weeks to 14 weeks, based on what she already knew. (I am a really serious advocate of this approach. I advocated to switch our entire first year for Engineering to a competency based approach but I’ll write more about that later on. And, no, we didn’t do it but at least we thought about it.)

In the mix are smaller chunks of information and just-in-time learning. Anyone who has used YouTube for a Photoshop tutorial has had a positive (well, as positive as it can be) experience with this. Why can’t we do this with any number of higher ed courses?

A note on the Stanford 2025 Design School exercise: the open loop education. Accepted to Stanford would give you access to 6 years of education that you would be able to use at any point in your life. Take two years, go out and work a bit, come back. Why isn’t the University at the centre of our lifelong involvement with learning?

The distance between producer and consumer is shrinking, whether it’s online stores or 3-D printing. Example given was MarginalRevolutionUniversity, a homegrown University, developed by a former George Mason academic.

As aways, the MOOC dropout rate was raised. Yes, only 10% complete, but Jeff’s interviews confirm what we already know, most of those students had no intention of completing. They didn’t think of the MOOC course as a course or as part of a degree, they were dipping in to get what they needed, when they needed it. Just like those YouTube Photoshop tutorials.

The difficult question is how certify this. And… here are badges again, part of certification of learning and the challenge is how we use them.

Jeff think that there are still benefits for residential experience, although assisted and augmented with technology:

- Faculty mentoring

- Undergraduate research (team work, open problems)

- Be creative. Take Risks. Learn how to fail.

- Cross-cultural experience.

Of course, not all of this is available to everyone. And what is the return on investment for this? LinkedIn finally has enough data that we can start to answer that question. (People will tell LinkedIn things that they won’t tell other people, apparently.) This may change the ranking game because rankings can now be conducted on outputs rather than inputs. Watch this space?

The world is changing. What does Jeff think? Ranking is going to change and we need to be able to prove our value. We have to move beyond isolated disciplines. Skill certification is going to get harder but the overall result should be better. University is for life, not just for three years. This will require us to build deep academic alliances that go beyond our traditional boxes.

Ok, prepping for the next talk!

Musing on Industrial Time

Posted: April 20, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, universal principles of design, work/life balance, workload 3 CommentsI caught up with a good friend recently and we were discussing the nature of time. She had stepped back from her job and was now spending a lot of her time with her new-born son. I have gone to working three days a week, hence have also stepped back from the five-day grind. It was interesting to talk about how this change to our routines had changed the way that we thought of and used time. She used a term that I wanted to discuss here, which was industrial time, to describe the clock-watching time of the full-time worker. This is part of the larger area of time discipline, how our society reacts to and uses time, and is really quite interesting. Both of us had stopped worrying about the flow of time in measurable hours on certain days and we just did things until we ran out of day. This is a very different activity from the usual “do X now, do Y in 15 minutes time” that often consumes us. In my case, it took me about three months of considered thought and re-training to break the time discipline habits of thirty years. In her case, she has a small child to help her to refocus her time sense on the now.

Modern time-sense is so pervasive that we often don’t think about some of the underpinnings of our society. It is easy to understand why we have years and, although they don’t line up properly, months given that these can be matched to astronomical phenomena that have an effect on our world (seasons and tides, length of day and moonlight, to list a few). Days are simple because that’s one light/dark cycle. But why there are 52 weeks in a year? Why are there 7 days in a week? Why did the 5-day week emerge as a contiguous block of 5 days? What is so special about working 9am to 5pm?

A lot of modern time descends from the struggle of radicals and unionists to protect workers from the excesses of labour, to stop people being worked to death, and the notion of the 8 hour day is an understandable division of a 24 hour day into three even chunks for work, rest and leisure. (Goodness, I sound like I’m trying to sell you chocolate!)

If we start to look, it turns out that the 7 day week is there because it’s there, based on religion and tradition. Interestingly enough, there have been experiments with other week lengths but it appears hard to shift people who are used to a certain routine and, tellingly, making people wait longer for days off appears to be detrimental to adoption.

If we look at seasons and agriculture, then there is a time to sow, to grow, to harvest and to clear, much as there is a time for livestock to breed and to be raised for purpose. If we look to the changing time of sunrise and sunset, there is a time at which natural light is available and when it is not. But, from a time discipline perspective, these time systems are not enough to be able to build a large-scale, industrial and synchronised society upon – we must replace a distributed, loose and collective notion of what time is with one that is centralised, authoritarian and singular. While religious ceremonies linked to seasonal and astronomical events did provide time-keeping on a large scale prior to the industrial revolution, the requirement for precise time, of an accuracy to hours and minutes, was not possible and, generally, not required beyond those cues given from nature such as dawn, noon, dusk and so on.

After the industrial revolution, industries and work was further developed that was heavily separated from a natural linkage – there are no seasons for a coal mine or a steam engine – and the development of the clock and reinforcement of the calendar of work allowed both the measurement of working hours (for payment) and the determination of deadlines, given that natural forces did not have to be considered to the same degree. Steam engines are completed, they have no need to ripen.

With the notion of fixed and named hours, we can very easily determine if someone is late when we have enough tools for measuring the flow of time. But this is, very much, the notion of the time that we use in order to determine when a task must be completed, rather than taking an approach that accepts that the task will be completed at some point within a more general span of time.

We still have confusion where our understanding of “real measures” such as days, interact with time discipline. Is midnight on the 3rd of April the second after the last moment of April the 2nd or the second before the first moment of April the 4th? Is midnight 12:00pm or 12:00am? (There are well-defined answers to this but the nature of the intersection is such that definitions have to be made.)

But let’s look at teaching for a moment. One of the great criticisms of educational assessment is that we confuse timeliness, and in this case we specifically mean an adherence to meeting time discipline deadlines, with achievement. Completing the work a crucial hour after it is due can lead to that work potentially not being marked at all, or being rejected. But we do usually have over-riding reasons for doing this but, sadly, these reasons are as artificial as the deadlines we impose. Why is an Engineering Degree a four-year degree? If we changed it to six would we get better engineers? If we switched to competency based training, modular learning and life-long learning, would we get more people who were qualified or experienced with engineering? Would we get less? What would happen if we switched to a 3/1/2/1 working week? Would things be better or worse? It’s hard to evaluate because the week, and the contiguous working week, are so much a part of our world that I imagine that today is the first day that some of you have thought about it.

Back to education and, right now, we count time for our students because we have to work out bills and close off accounts at end of financial year, which means we have to meet marking and award deadlines, then we have to project our budget, which is yearly, and fit that into accredited degree structures, which have year guidelines…

But I cannot give you a sound, scientific justification for any of what I just wrote. We do all of that because we are caught up in industrial time first and we convince ourselves that building things into that makes sense. Students do have ebb and flow. Students are happier on certain days than others. Transition issues on entry to University are another indicator that students develop and mature at different rates – why are we still applying industrial time from top to bottom when everything we see here says that it’s going to cause issues?

Oh, yes, the “real world” uses it. Except that regular studies of industrial practice show that 40 hour weeks, regular days off, working from home and so on are more productive than the burn-out, everything-late, rush that we consider to be the signs of drive. (If Henry Ford thinks that making people work more than 40 hours a week is bad for business, he’s worth listening to.) And that’s before we factor in the development of machines that will replace vast numbers of human jobs in the next 20 years.

I have a different approach. Why aren’t we looking at students more like we regard our grape vines? We plan, we nurture, we develop, we test, we slowly build them to the point where they can produce great things and then we sustain them for a fruitful and long life. When you plant grape vines, you expect a first reasonable crop level in three years, and commercial levels at five. Tellingly, the investment pattern for grapes is that it takes you 10 years to break even and then you start making money back. I can’t tell you how some of my students will turn out until 15-25 years down the track and it’s insanity to think you can base retrospective funding on that timeframe.

You can’t make your grapes better by telling them to be fruitful in two years. Some vines take longer than others. You can’t even tell them when to fruit (although can trick them a little). Yet, somehow, we’ve managed to work around this to produce a local wine industry worth around $5 billion dollars. We can work with variation and seasonal issues.

One of the reasons I’m so keen on MOOCs is that these can fit in with the routines of people who can’t dedicate themselves to full-time study at the moment. By placing well-presented, pedagogically-sound materials on-line, we break through the tyranny of the 9-5, 5 day work week and let people study when they are ready to, where they are ready to, for as long as they’re ready to. Like to watch lectures at 1am, hanging upside down? Go for it – as long as you’re learning and not just running the video in the background while you do crunches, of course!

Once you start to question why we have so many days in a week, you quickly start to wonder why we get so caught up on something so artificial. The simple answer is that, much like money, we have it because we have it. Perhaps it’s time to look at our educational system to see if we can do something that would be better suited to developing really good knowledge in our students, instead of making them adept at sliding work under our noses a second before it’s due. We are developing systems and technologies that can allow us to step outside of these structures and this is, I believe, going to be better for everyone in the process.

Conformity isn’t knowledge, and conformity to time just because we’ve always done that is something we should really stop and have a look at.

That’s not the smell of success, your brain is on fire.

Posted: February 11, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, Henry Ford, higher education, in the student's head, industrial research, learning, measurement, multi-tasking, reflection, resources, student perspective, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, working memory, workload Leave a commentI’ve written before about the issues of prolonged human workload leading to ethical problems and the fact that working more than 40 hours a week on a regular basis is downright unproductive because you get less efficient and error-prone. This is not some 1968 French student revolutionary musing on what benefits the soul of a true human, this is industrial research by Henry Ford and the U.S. Army, neither of whom cold be classified as Foucault-worshipping Situationist yurt-dwelling flower children, that shows that there are limits to how long you can work in a sustained weekly pattern and get useful things done, while maintaining your awareness of the world around you.

The myth won’t die, sadly, because physical presence and hours attending work are very easy to measure, while productive outputs and their origins in a useful process on a personal or group basis are much harder to measure. A cynic might note that the people who are around when there is credit to take may end up being the people who (reluctantly, of course) take the credit. But we know that it’s rubbish. And the people who’ve confirmed this are both philosophers and the commercial sector. One day, perhaps.

But anyone who has studied cognitive load issues, the way that the human thinking processes perform as they work and are stressed, will be aware that we have a finite amount of working memory. We can really only track so many things at one time and when we exceed that, we get issues like the helmet fire that I refer to in the first linked piece, where you can’t perform any task efficiently and you lose track of where you are.

So what about multi-tasking?

Ready for this?

We don’t.

There’s a ton of research on this but I’m going to link you to a recent article by Daniel Levitin in the Guardian Q&A. The article covers the fact that what we are really doing is switching quickly from one task to another, dumping one set of information from working memory and loading in another, which of course means that working on two things at once is less efficient than doing two things one after the other.

But it’s more poisonous than that. The sensation of multi-tasking is actually quite rewarding as we get a regular burst of the “oooh, shiny” rewards our brain gives us for finding something new and we enter a heightened state of task readiness (fight or flight) that also can make us feel, for want of a better word, more alive. But we’re burning up the brain’s fuel at a fearsome rate to be less efficient so we’re going to tire more quickly.

Get the idea? Multi-tasking is horribly inefficient task switching that feels good but makes us tired faster and does things less well. But when we achieve tiny tasks in this death spiral of activity, like replying to an e-mail, we get a burst of reward hormones. So if your multi-tasking includes something like checking e-mails when they come in, you’re going to get more and more distracted by that, to the detriment of every other task. But you’re going to keep doing them because multi-tasking.

I regularly get told, by parents, that their children are able to multi-task really well. They can do X, watch TV, do Y and it’s amazing. Well, your children are my students and everything I’ve seen confirms what the research tells me – no, they can’t but they can give a convincing impression when asked. When you dig into what gets produced, it’s a different story. If someone sits down and does the work as a single task, it will take them a shorter time and they will do a better job than if they juggle five things. The five things will take more than five times as long (up to 10, which really blows out time estimation) and will not be done as well, nor will the students learn about the work in the right way. (You can actually sabotage long term storage by multi-tasking in the wrong way.) The most successful study groups around the Uni are small, focused groups that stay on one task until it’s done and then move on. The ones with music and no focus will be sitting there for hours after the others are gone. Fun? Yes. Efficient? No. And most of my students need to be at least reasonably efficient to get everything done. Have some fun but try to get all the work done too – it’s educational, I hear. 🙂