ITiCSE 2025: Working Group 1 – exciting news!

Posted: February 14, 2025 Filed under: Education | Tags: computer science education research, education, games, higher education, ITiCSE, learning, play, research, teaching, technology, thinking Leave a commentTwo posts in the same year? Something must be up… and it is! After the successful presentation of Dr Rebecca Vivian and my work at Koli as both DC tool and award winning poster/demo, I looked into taking this to a working group and Dr Miranda Parker agreed to co-lead it with me, as Rebecca is currently on leave. Miranda and I have been digging into all of the aspects of this in the middle of both our day jobs and it’s been a lot of fun to work on! You think you’ve got difficult collaborators? Miranda has to listen to me pontificate about ontologies, paradigms, and philosophies!

It’s really important to recognise Rebecca’s ongoing connection with this project, as it’s still very much Rebecca’s work that got us here and she will continue to be a significant part of this, we’re just making sure we have the co-leadership of people who aren’t on leave to make it work. It’s really exciting that our Workgroup has gone to the advertisement stage!

You can see all of the WG proposals here, and sign up (maybe to ours if you like what you read here) here. We’re happy to answer questions and it’s going to be an amazing combination of serious play, serious research, and great fun.

Here’s the ad as a cut and paste!

WG1 – Paradigms, Methods, and Outcomes, Oh My!: Refining and Evolving a Research Knowledge Development Activity for Computer Science Education

Leaders:

- Nick Falkner, nickolas.falkner@adelaide.edu.au

- Miranda Parker, miranda.parker@uncc.edu

Motivation:

Computer Science Education Research (CSER) combines the frequently quantitative approaches of computer science, engineering, and mathematics with the often more qualitative techniques seen in psychology, sociology, behavioural science, and education. It can be challenging to select appropriate research methods in effective and efficient ways.

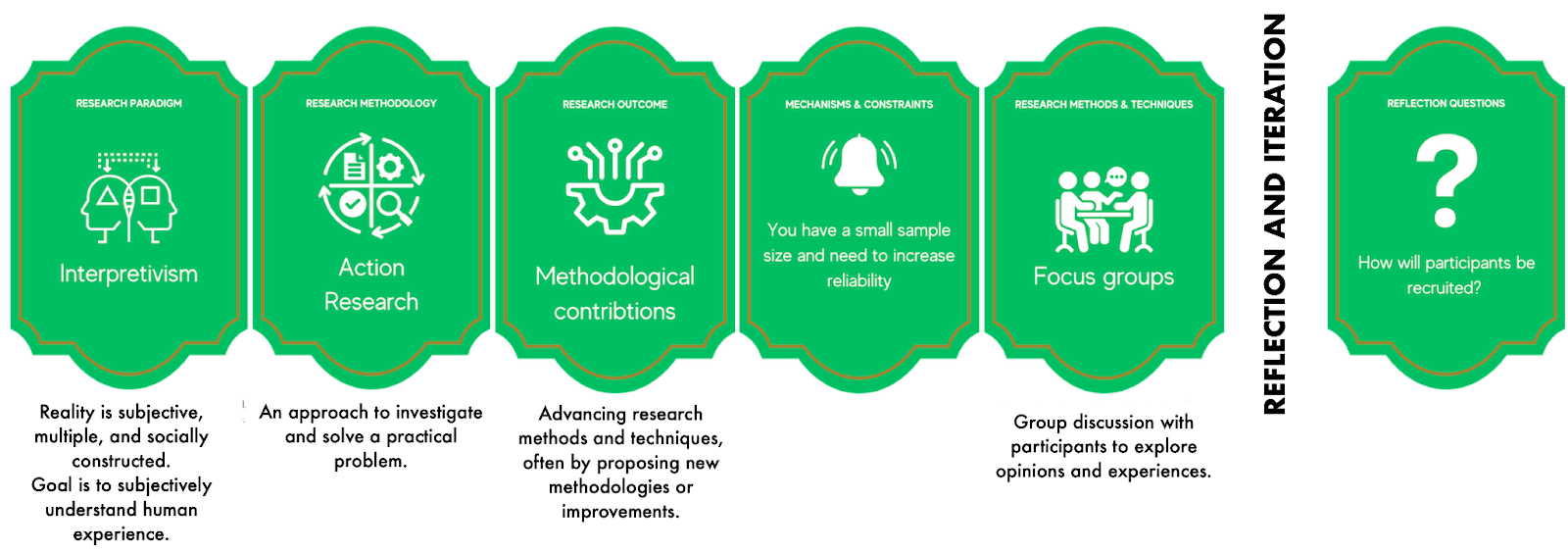

Inspired by the use of card-based techniques in the classroom, the Research Alternatives Exercise (RAE) is a pack of 105 cards introducing a wide range of possible research approaches. RAE provides alternatives to a participant’s current research plans using new random lenses, leading to the sketch of a new research design. The participant refers to their own design through the lens of the randomly drawn card, working to see how well this fits, informs, or improves what they have done.

The initial version of the card deck and examples of play won best paper/demo at Koli Calling 2024 and an example “run” is shown below:

Goals:

- review and modify the existing deck through collaboration in the WG

- develop a version of the deck that can be shared and used widely across the CSER community,

- develop a concise support glossary for the cards

Methodology:

The current deck will be shared with participants, to support targeted literature review, research, and consultation to:

- refine the terminology used for categories, which are currently paradigms, methodologies, outcomes, and methods,

- refine the components within categories,

- review the existing rules for suitability,

- develop the first draft of the support glossary, and

- develop different decks and play approaches for specific purposes.

Following kickoff at the end of March, we will work on Items 1 and 3, aiming for completion by the start of May. When categories are finalized, we will undertake Item 2, where each group member will work in small groups to review each category. Findings will be presented to the whole group by the beginning of June, for further discussion and collaboration. Each sub-group will be responsible for the glossary elements of their contribution, to be completed and reviewed for the start of the in-person WG time. Each working group member will be asked to share the deck with colleagues to provide feedback.

Member Selection:

We seek at least 8-10 individuals to share the required work manageably.

We are looking for participants with at least one of:

- Experience with a wide variety of research methodologies,

- Experience in supervising graduate students,

- Interest and knowledge in using game-based and facilitated techniques, or

- Experience with research skills development.

We actively invite applications from disciplines beyond computing for diversity in research skills development experience. We seek a diversity of experience, background, and culture, to ensure that the feedback encompasses the full range of CSER community experience. We also welcome student applications.

Successful applicants will:

- Attend fortnightly 60-90 minute online progress meetings, held from mid-late March to the end of June,

- Register for ITiCSE 2025,

- Physically attend the full duration of the working group, and

- Make significant contributions during the pre- and post-ITiCSE Working Group activities (3-4 hours a week).

Books about Play

Posted: January 27, 2025 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: books, education, games, gaming, play, reading, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentBeing a subset of interesting books from my collection, accompanied with explanatory texts of varying utility, as well as references to this blog.

A very rapid summary in far too much detail.

I recently had reason to distill my thoughts on why games, play, and the playing of games were a valid and even necessary area of discussion when talking about education. Some collaborators and I have been working on a new way to assist in research skills development that uses play mechanisms. I have had a lot of opportunity to read and think about this but I wanted to get it out of my head so other people could also understand why I thought the way that I did.

However, I realised when I was trying to write up my books about games and play, that I had quite a large amount of philosophy and theory behind it, as well as some motivating examples from other educators. I can direct people to the books but unless I really explain at least some of the journey, the books are just islands of fact in a desert, when really most of what I have here are stations on a longer and much more detailed journey. As with everything, it is not the fact, it is the context in which you encounter it and your mood and willingness to engage when that fact and context are coincident.

I also realise that there is a chance that anyone reading this may need to skim this. You will still have the books by name, which achieves the initial goal, and it is quite useful for me to write all of this up so that I have a record of it, should anyone else ask. The excuse to do this has allowed me to invest the effort, doubly so now that I have modified the original version of the text for publication on my (long dormant) education blog.

The layout of the following sections will be a collection of books and then some discussion as to why they’re here. Some are just good examples, some are more illustrative, some are essential. I shall attempt to make the difference clear.

Robert A. Sage

Myth

Theodor W. Adorno

Aesthetics

Genis Carreras

Philographics

Don Norman

The Design of Everyday Things

Myth: Robert A. Segal

Play is a fundamental part of being alive, for many creatures, not just us. Because we can’t communicate well with other species, it can be very hard to understand what is a habit or somehow driven by the surroundings, what is a (conscious?) choice for a creature to under a serious action, and what is play: to engage in activity for recreational purposes or enjoyment.

Obviously, many activities have both serious and play applications, so understanding whether an activity is play or serious cannot be determined simply by observing. For me, my pathway to understanding play began by seeking to understand how we, the human we, work with information, how we process what has gone before, how we understand it, label it, categorise it, express it, communicate it, and interact with it.

Thus I started with trying to understand how we formed the understanding of our early selves. I have had a number of books on the formation of human myth, how we talk about our pre-history and pre-written selves. There are many books of myth but I like this (tiny) Oxford University Press book from Segal about contemporary theories of myth, which contains the great truth that theories of myth are often subsets of some larger theory from a given discipline restricted to the area of myth.

Myths are not just stories in word or voice, but there is often a tie to ritual, physical activities that are associated with a long held traditional story or belief. This book covers many angles of the theory of myth, discussing in brief many approaches, and it was a (much larger but) similar text that led me to understand the importance of the physical in story-telling and communication.

A good story has many elements to it, in the use of voice and physical theatre, in the choice of location, even down to the timing of the tale and its cadence. But we only have to look to puppetry, an ancient art, or how children react to the use of small wooden animals, to see how quickly our minds can wrap narrative and assistive explanatory tool together. The idea that this could reinforce a ritual, reinforce a memory, and hence give us a mythic form that might carry information forward comes from books like this.

To restrict the domain of play to either the physical or the non-physical is to ignore the reality that we engage in physical and intellectual pursuits for our own amusement. From a personal angle, I am a somewhat infamous juggler of words, which is more intellectual, but I was for many years a keen underwater swimmer, as my terrible swimming style is no disadvantage when submerged. Water was my medium of play for many long Australian summers, as long as I could stay underneath it competing with my friends, diving for thrown objects, or diving to the bottom of the deepest pools I could find. It was a break from reality, a different space altogether: concepts I shall return to later on. Play has turned out to a very natural thing for me, but it took a lot of reading to understand how essential it was to my humanity and my serious work as well.

Theodor W. Adorno – Aesthetics

The next book is a rather odd choice as this is a set of lectures delivered by Adorno in 1958-59, which he used to base a book on … that he never finished. Theodor W. Adorno was a German philosopher, musicologist, and social theorist. He was a leading member of the Frankfurt School of critical theory and wrote many fascinating works including the amazing “Minima Moralia“, which is worth looking at in its own right as it is a collection of short themed observations, many of which are profound in their expression and content. However, this book is here for two reasons:

- His definitions of aesthetics from Kant and Hegel and the ongoing discussion throughout the book are some of the clearest I’ve seen and show very clearly the difference between “aesthetic as decoration” and “aesthetic as fitness for.. everything”.

- His deep commitment to interactive work with his students, where his own intellectual understanding of the work and his desire to present it in an engaging manner resulted in his own students not quite following. Rather than not following, he corrected himself and reset his context. Reading this book shows you a masterful thinker and philosopher being relatively really rather humble and I love it for that alone.

Returning briefly to point 1, I shall recall that aesthetics can be briefly described as the philosophy of the principles of beauty (among other things). Well, what then is beauty? I’m glad you asked. Kant basically defined beauty as everything attractive that was not useful – a ‘disinterested pleasure’. For example, an apple could be beautiful and hence aesthetically pleasing until you ate it, at which point your interaction was animal and essentialist – having found function/value, your interaction was no longer aesthetic. Hegel disagreed, quelle surprise, with Kant and redefined beauty as “the sensual appearance of an idea”. Now we could still interact with something in meaningful ways and indeed incorporate function into our definition of beauty.

This immediately admits the aesthetic of form in function, where aesthetically pleasing objects are also excellent examples of form, as is seen in a great deal of Japanese and Scandinavian artisanal handicraft, where function without good form is anathema.

You have to read the book to find out how much Hegel then went on to get wrong, according to Adorno, but one more thing to remember is that Adorno rejected aesthetic sensibilities as somehow objective or rigid, they were strongly associated with whatever matter you were regarding and that was where you derived their sense. This notion of relativism is quite liberating, as it allows for a multiplicity of aesthetic interpretations.

Genis Carreras – Philographics

This is a recent addition to my collection and I bought because it was a reminder of the complex pathway people have taken in their attempts to render complex concepts as simply symbols. One of my many interests is in wayfinding, in the physical and intellectual sense; this being the work of communicating pathways and directions to other people. This leans heavily on semiotics, the study of signs and symbols and their interpretation, as no map for wayfinding would work without a very clear sign vocabulary.

There are so many books I could put here but this is already long enough. This book is here as a simple symbolic placeholder to the importance of agreed contexts for shared understanding of symbolic representations, a vital part of the language of play. The range of human interpretation of words, actions, and symbols is vast and understanding if someone is playful or serious often hinges on this understanding. (Consider the Australian slang ‘sport’, which can be one of the most serious and threatening words anyone hears. It is not clear at all that this is the verbal equivalent of three giant flashing red lights and a tornado siren.)

Contrast this with the two images from this book, which seek to explain different concepts with simple symbols. Do they work? Perhaps. Are they interesting to consider, to view as guides to our own symbolic representation, and thus the way that we could consider play? Definitely.

Don Norman – The Design of Everyday Things

And here we are with the classic. How does the great naked ape, Homo Sapiens Sapiens, interact with the elements of its world? Norman’s book explains mugs, handles, defining the requirements of the things that a human is going to try to use in their pursuit of love, life, and work. In design, affordances, what the environment offers the individual, are reduced to what actions you can perceive are valid with an object. I have often extended this into the ethical sphere, as I believe that well-defined ethics provide the affordances for living with other people: what are the valid “handles” that one can “grab” and still be considered part of the in-group?

From a play perspective, we are back in the realm of semiotics: what do I need to show you so that you understand that the available affordances are playful rather than serious? What does that even mean?

I also find Norman invaluable for thinking about requirements analysis, as a simple affordance test on a prototype is a great way to show you all the things that actual people will do. Of course, in HCI and UI-design, the fact that you cannot predict everything a human will do is often a core concern, but reading Norman can help you to think about finding a coherent interaction model despite that.

Summary

So we’ve looked at the way we talk about ourselves, to understand how we might communicate play and serious, started a definition of aesthetics, wandered into wayfinding, and appreciated affordances. Let’s walk a little further into design before we finally start talking about texts that describe play.

Helen Cann

Hand Drawn Maps

Tomitsch et al

Design. Think. Make. Break. Repeat.

Bleecker et al

The Manual of Design Fiction

Roger Caillois

Man, Play, and Games

Helen Cann – Hand Drawn Maps

Again, there could be many books here. There is always Korzybski’s “The Map is not the Territory”, which is a very solemn version of “All models are incomplete but some are useful.” Maps are representations of something in the/a world, most often visual and two-dimensional, showing the things that are of interest to the map maker and also hopefully the map user. (Korzybski’s statement may be read as that if something was exactly the same as what it was mapping, it would be the thing – therefore, all maps are not exactly the same so what do you choose to change.)

I like public transit maps, because they so clearly show how you can get around cities, are almost always well-designed, and have to be useful to a large number of busy people. They are some of the most effective maps you’ll ever see because they have to be.

Amusingly, the London Underground Map is only useful underground. There had to be an active “London aboveground” program to show Londoners how to navigate the world above, because some things shown on the Underground map gave a totally false impression of what sensible aboveground navigation would look like. Why? Because the underground map prioritises connections, a breakthrough design by Harry Beck in the 1930s because he represented everything as a schematic diagram, rather than a mapping of the geographical reality. People on trains don’t need to know if the track is straight or curved, they need to know how many stations until they connect to go three more stations to Tooting Bec. I wrote a lot more about this about ten years ago.

Helen Cann’s book takes a playful perspective on maps and is aimed solidly at people who are building maps for fun, which is why it’s here instead of some other very serious books. It contains many creative prompts for building visual 2D imagery that conveys spatial and other relationships in a way that helps you navigate them. Maps, boards, cards, and games are all linked in my head and her book helps to understand why this is and why they are all subtly different.

This also admits the kind of graph/connection thinking that we see in the works of Franco Moretti – the Distant Reading Guy – where he carries out corpus analysis and NLP to derive relationships, determine changes, and explore hypotheses, without necessarily every personally reading the text. I like his stuff as a tool but I’m not sure I buy it as a solid methodology. Again, there’s a couple of blog posts on this here. Maps are fun!

Tomitsch et al – Design. Think. Make. Break. Repeat.

This is a book of design methods, roughly 60 different ways to engage in design with many perspectives and disciplines. It’s basically a short reference to scaffold the development of knowledge in the area of design: from product design to user experience and much in-between. I like this book for several reasons:

- Each section has a clear description, a reference list, step-by-step exercises, and a number of handy templates you can just start using.

- It’s very focused on getting you started trying something, to build knowledge through hands-on attempts.

- It has some really interesting case studies at the back.

I haven’t just learned about design from this book, I’ve learned about how to learn about design, and how I could construct other materials to make learning easier. This book has helped me to communicate ideas about play.

Bleecker et al – The Manual of Design Fiction

The last of the design books! Design fiction is probably one of my favourite things (I have many and don’t usually rank them so this is less exclusive than it may seem). At its heart, design fiction is the deliberate construction of narrative prototypes to suspend disbelief about the possibility and benefit of change. It is, like all fiction, inherently playful. We are building castles in the air and then sending in virtual construction inspectors to find our faults! How much more fantastically playful can we get?

This work is part of the core thinking about play and the research skills development tool that colleagues and I are working on. How can I get someone to understand that there might be another way to undertake their research? Let me rewrite that: how can I reduce the barriers to explore change? How do I encourage people to consider that there may be techniques and thinking that are not nonsense from other disciplines but valid contributors to academia? Again, let me rewrite that: how can I change your mind about which paradigms and methodologies are valid?

This book is a touch focused in the physical/reification space when, to me, design fiction has as much, if not more validity, in the area of ideation and knowledge development – this may all be nuance and I may just need to think more. It’s still a really interesting read and will add enormous amounts of interesting food for thought around group work, collaboration, and skill development.

Roger Caillois – Man, Play, and Games

I am deliberately presenting this book first, although it is very much a reaction to the next book, Homo Ludens. Caillois’ book is about the definition of what play is, with a wide range of culturally located definitions of the key games of given peoples, linking games even to moral aspects of culture, defining customs and institutions.

He accepts the essential need of humans to play and defines it (partially) as a voluntary sidestep from the realities of life, wherein rules constrain action and we all move to some outcome that has at least some randomness in its achievement. Children tend to improvise more, adults tend to strategise more, an increase of discipline with age and knowledge, perhaps or just another custom? He links some games back to mythic connection, where the games played by children mimic the actions of gods long ago, sometime deliberately as part of religious practice.

There are any number of important terms introduced here, including alea, which is best understood as chance but has many other meanings. When Julius Caesar took his armies across the Rubicon and into Rome, to take it as Emperor, he is supposed to have said “Alea iacta est.” which means “The die has been cast/I have taken my chance.” This statement is significant in its appeal to the fates, but also a recognition of uncertainty and a clear statement of bravado! (Recall that the study of probability is terrifyingly recent and many earlier cultures regarded what we would think of as random outcomes as clear indicators of favours granted by supernatural powers.)

Caillois took issue with Huizinga’s work, as he felt it lacked recognition of the variations of play and the needs served by play in a cultural context. While Caillois is, to me, the better text in terms of its utility because of its cultural inclusion, it’s still important to read Huizinga.

Summary

All of this is designed to provide tools, vocabulary, and background to really start to understand that games are important, culturally and personally, which provides us with a way to discuss useful games in well-defined manner. One of the biggest problems with educational games is that they are often a non-game activity which has had game elements bolted onto it. That does not make it a game, nor does it make it play. We shall return to this.

Johan Huizinga

Homo Ludens

Bernard Suits

The Grasshopper

Eric Zimmerman

The Rules We Break

Helen Fioratti

Playing Games

Johan Huizinga – Homo Ludens

At its core, Homo Ludens is about the necessity of play to culture and society. Animals play, but humans play in ways that assist us in becoming more than a small in-group, limited by the Dunbar limit and the size of our cerebellum. Play, to Huizinga, is one of the primary drivers that creates culture and is necessary if we are to generate culture. (We need more than play but there must be play.)

Huizinga, in a rather dour way, leads off with the fact that play must be fun, which is why animals also do it despite many of the playful species lacking the additional brain stuff that we and other sentients or proto-sentients appear to have.

As Caillois agreed with (mostly), Huizinga had five rules: that play is free, it is not everyday life and in fact it is noticeably different from everyday life, play has a sense of absolute order (think rules here), and nobody actually benefits in any real or monetary sense from play.

Play was not just free, play was freedom, and that concept explains a lot of the subsequent rules and text. Although Huizinga did not follow up on culture as Caillois would have liked, he did note that cultural perceptions change the nature of play: while western children might pretend to be an animal, a first-nations’ shaman would be culturally considered to have become one. Even the way that we talk about play shows how fragile our definitions are once we start thinking.

My paraphrase of all of this is that once we engage someone in play, they will potentially engage with the activity that we had planned, all the while inhabiting a totally different context due to their own cultural experience and perception.

This is not a book I can summarise easily as it has an enormous amount of classification, ideas, and content. I will share some important ideas from or derived from the work that I am using in developing new tools:

- The “magic circle”: this is the space in which the normal rules of reality are suspended and others now apply.

- The notion of metaphor as play, the metaphorical representation of wisdom/lesson as god forming myth in a model that is inherently playful. Thus all myth-making, a strong civilising force, is a playful activity.

- Poetry is play. I just like this one.

Bernard Suits – The Grasshopper

Words cannot contain how much I love this book. Suits takes direct aim at Wittgenstein’s assertion that definition is impossible, demonstrated by an inability to define what games are, by providing a definition. But he does so through the most charming and heart-wrenching of conceits. You are probably familiar with the fable of the hard working ants and the lazy grasshopper, where the ants worked all summer and the grasshopper just played music, then winter came and the ants lived and the grasshopper died because … ants are just not very nice, apparently. The conceit at the core of “The Grasshopper” is that the grasshopper is a philosopher of play and can thus not commit to beneficial labour as it contradicts his principles. He makes great contributions in his philosophical discourse with his students (ants dressed up as grasshoppers), who beseech him to take food that they have worked for, for him, but he refuses, committed at the deepest level to his philosophy of play.

Suits’ rules (slightly paraphrased) are:

- There are a set of rules for the game

- You cannot take the most direct path to achieve the outcome

- Players willingly accept both the previous rules, adopting a ludic mindset.

As you can see, we’re back in the realm of an excursion from reality, with its own rules, mind space, and no definition of benefit. In fact, the Grasshopper provides an example of total detriment by comparison but he would rather die firm in his philosophy than give up his principles

I am not doing this book justice, but I hope I am conveying its essence. I draw on this in a lot of what I do, as a communicator, because I am always seeking to draw people into a semi-ludic space to explore new ideas and I must have their consent and commitment to the ludic mindset to do it: people must give themselves the authority and freedom to play.

Eric Zimmerman – The Rules We Break

This is a book about how to actually make games but also how to evolve and adapt games. Zimmerman goes through possible problems with games and is also reinforcing all the things that people want to see in games: is a game too predictable, does a winner emerge too early, do people drop out too fast, or is it simply “not fun”?

There are many notionally educational games that are merely the activity in question with a strange game frame around, in the style of “Let’s get to Mars by solving this algebra problem”, which often fall very rapidly into the “not fun” category because it’s not a game at all. It’s a learning activity with set process and correct outcome, wearing some silly clothes.

This is another book about design, very hands on, and built to try things. Imagine running students through a redevelopment of a combined text generation exercise as a game where one student writes the title, another writes the slug, another writes key elements, but they only have two words to do it from without any discussion, then they combine it and look at the whole they’ve created from that cue. Not only does this book drive that sort of creativity, it helps you to analyse whether it’s working and how to fix it.

You will look at games differently after reading this book AND have lots of great things to try in the classroom.

Helen Fioratti – Playing Games

Again, many books could be here but I have a soft spot for this one as I picked it up in Florence while I was starting my ponderings about games. There are so many different games in the world, card games alone would keep you busy for a lifetime, let alone variants on boardgames.

In many ways, understanding what has gone before is both informative and interesting, and understanding the rise of new games as new technologies or practices emerged is important to thinking about games in general. Why did a certain game gain a particular variant? How do games change when they are played with a “house” (casino) vs playing against other people?

As I noted, there was a time where people played games of chance without understanding probability. Oh wait, that’s Vegas. I’ve never been to Vegas because it scares the hell out of me – it’s like a trap invented for people who sometimes think that they are more clever than they are.

Games are part of who we are, who we were, and who we hope to be. A good historical reference of games is essential and this one is quite acceptable.

Summary

I hope that I have now motivated why play is both essential and useful as a tool, given that it allows us to move into another space with other rules – ideal for us seeking to get students to experiment and engage in new spaces with less overhead. So let’s get to the final two books in my collection that are relevant here.

Peterson and Smith

The Rapid Prototyping Game

Engelstein and Shalev

Building blocks of Tabletop Design

Engelstein and Shalev – Building Blocks of Tablerop Game Design

An incredible reference and the most amazing way to understand every game you’ve every played and every game mechanic you’ve ever used elsewhere. It’s almost impossible to read sequentially as, despite being very thorough and technically interesting, it’s an encyclopaedia, not a narrative work.

In many ways it’s the archetype (with the design guide above) of the written work that I discuss below: a well-written, technically correct, and thorough capture that introduces every important concept, paradigm, framework, methodology etc.

It also gives an example of the way that categories matter in the formation of the work. A different set of categorisation choices would put some things in a very, very different place.

Peterson and Smith – The Rapid Prototyping Game

Finally, the cards that inspired the tool that I’m currently working on – there are substantial and meaningful differences but the cards themselves made me think of what else we could do. Smith wanted to teach his game design students other techniques and wanted to engage them and mentioned to Peterson that he wanted a good range of techniques to draw from. You can find his own blog on this here. Smith found the encyclopaedia above (Engelstein and Shalev) and thought it was a great resource that he could turn into a playful activity by using cards. Why? because what he was trying to do wasn’t working

“You see, the students were still struggling. They were afraid of failing. They were unoriginal. They made games like Chutes and Ladders or Monopoly.”

Smith, https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/the-rapid-prototyping-game

His goal: build something the students could play with that broke a complex task down into well-defined and manageable categories that enabled the students to isolate particular categories and work on them. Decomposition, simplification, and information management all being used to make something complex far easier to work with. By using random allocation, via the cards, he was able to break students out of their “I’m going to make Monopoly” because they might not get the elements to do it – in fact, it was quite unlikely.

Smith and Peterson’s model used three dice throws to establish medium (board, card,…) , format (competitive, cooperative,…) , and objective (exploration, building,…). Then they used four decks of cards to let students draw from a much larger range of options for Mechanics, Themes, Victory Condition and Turn Order.

For the tool I’m working on, we have more decks of cards, because a 6-sided die only allows six options, whereas we often have up to twenty. While what I’m doing is definitely inspired by this approach, it is more inspired by the idea of play as a super-positional rule space that allows exploration in a free space with different rules, which I approach far more formally than the original card authors do.

Final Summary

Thus, my books on play along with, not promised at all, an unpacking of my process that led towards the idea that my wonderful colleague Dr Rebecca Vivian then reified as the cards themselves. I hope to be able to share more on this soon.

Large Scale Authenticity: What I Learned About MOOCs from Reality Television

Posted: March 8, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, design, education, ethics, feedback, games, higher education, MKR, moocs, My Kitchen Rules, principles of design, reflection, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking 1 CommentThe development of social media platforms has allows us to exchange information and, well, rubbish very easily. Whether it’s the discussion component of a learning management system, Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Snapchat or whatever will be the next big thing, we can now chat to each other in real time very, very easily.

One of the problems with any on-line course is trying to maintain a community across people who are not in the same timezone, country or context. What we’d really like is for the community communication to come from the students, with guidance and scaffolding from the lecturing staff, but sometimes there’s priming, leading and… prodding. These “other” messages have to be carefully crafted and they have to connect with the students or they risk being worse than no message at all. As an example, I signed up for an on-line course and then wasn’t able to do much in the first week. I was sitting down to work on it over the weekend when a mail message came in from the organisers on the community board congratulating me on my excellent progress on things I hadn’t done. (This wasn’t isolated. The next year, despite not having signed up, the same course sent me even more congratulations on totally non-existent progress.) This sends the usual clear messages that we expect from false praise and inauthentic communication: the student doesn’t believe that you know them, they don’t feel part of an authentic community and they may disengage. We have, very effectively, sabotaged everything that we actually wanted to build.

Let’s change focus. For a while, I was watching a show called “My Kitchen Rules” on local television. It pretends to be about cooking (with competitive scoring) but it’s really about flogging products from a certain supermarket while delivering false drama in the presence of dangerously orange chefs. An engineered activity to ensure that you replace an authentic experience with consumerism and commodities? Paging Guy Debord on the Situationist courtesy phone: we have a Spectacle in progress. What makes the show interesting is the associated Twitter feed, where large numbers of people drop in on the #mkr to talk about the food, discuss the false drama, exchange jokes and develop community memes, such as sharing pet pictures with each other over the (many) ad breaks. It’s a community. Not everyone is there for the same reasons: some are there to be rude about people, some are actually there for the cooking (??) and some are… confused. But the involvement in the conversation, interplay and development of a shared reality is very real.

And this would all be great except for one thing: Australia is a big country and spans a lot of timezones. My Kitchen Rules is broadcast at 7:30pm, starting in Melbourne, Canberra, Tasmania and Sydney, then 30 minutes later in Adelaide, then 30 minutes later again in Queensland (they don’t do daylight savings), then later again for Perth. So now we have four different time groups to manage, all watching the same show.

But the Twitter feed starts on the first time point, Adelaide picks up discussions from the middle of the show as they’re starting and then gets discussions on scores as the first half completes for them… and this is repeated for Queensland viewers and then for Perth. Now , in the community itself, people go on and off the feed as their version of the show starts and stops and, personally, I don’t find score discussions very distracting because I’m far more interested in the Situation being created in the Twitter stream.

Enter the “false tweets” of the official MKR Social Media team who ask questions that only make sense in the leading timezone. Suddenly, everyone who is not quite at the same point is then reminded that we are not in the same place. What does everyone think of the scores? I don’t know, we haven’t seen it yet. What’s worse are the relatively lame questions that are being asked in the middle of an actual discussion that smell of sponsorship involvement or an attempt to produce the small number of “acceptable” tweets that are then shared back on the TV screen for non-connected viewers. That’s another thing – everyone outside of the first timezone has very little chance of getting their Tweet displayed. Imagine if you ran a global MOOC where only the work of the students in San Francisco got put up as an example of good work!

This is a great example of an attempt to communicate that fails dismally because it doesn’t take into account how people are using the communications channel, isn’t inclusive (dismally so) and constantly reminds people who don’t live in a certain area that they really aren’t being considered by the program’s producers.

You know what would fix it? Putting it on at the same time everywhere but that, of course, is tricky because of the way that advertising is sold and also because it would force poor Perth to start watching dinner television just after work!

But this is a very important warning of what happens when you don’t think about how you’ve combined the elements of your environment. It’s difficult to do properly but it’s terrible when done badly. And I don’t need to go and enrol in a course to show you this – I can just watch a rather silly cooking show.

Rules: As For Them, So For Us

Posted: November 17, 2014 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, collaboration, community, Dog Eat Dog, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, games, Generation Why, higher education, learning, measurement, student, student perspective, students, teaching, teaching approaches, time banking 1 CommentIn a previous post, I mentioned a game called “Dog Eat Dog” where players role-play the conflict between Colonist and Native Occupiers, through playing out scenarios that both sides seek to control, with the result being the production of a new rule that encapsulates the ‘lesson’ of the scenario. I then presented education as being a good fit for this model but noted that many of the rules that students have to be obey are behavioural rather than knowledge-focussed. A student who is ‘playing through’ education will probably accumulate a list of rules like this (not in any particular order):

- Always be on time for class

- Always present your own work

- Be knowledgable

- Prepare for each activity

- Participate in class

- Submit your work on time

But, as noted in Dog Eat Dog, the nasty truth of colonisation is that the Colonists are always superior to the Colonised. So, rule 0 is actually: Students are inferior to Teachers. Now, that’s a big claim to make – that the underlying notion in education is one of inferiority. In the Dog Eat Dog framing, the superiority manifests as dominance in decision making and the ability to intrude into every situation. We’ll come back to this.

If we tease apart the rules for students then are some obvious omissions that we would like to see such as “be innovative” or “be creative”, except that these rules are very hard to apply as pre-requisites for progress. We have enough potential difficulty with the measurement of professional skills, without trying to assess if one thing is a creative approach while another is just missing the point or deliberate obfuscation. It’s understandable that five of the rules presented are those that we can easily control with extrinsic motivational factors – 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 are generally presented as important because of things like mandatory attendance, plagiarism rules and lateness penalties. 3, the only truly cognitive element on the list, is a much harder thing to demand and, unsurprisingly, this is why it’s sometimes easier to seek well-behaved students than it is to seek knowledgable, less-controlled students, because it’s so much harder to see that we’ve had a positive impact. So, let us accept that this list is naturally difficult to select and somewhat artificial, but it is a reasonable model for what people expect of a ‘good’ student.

Let me ask you some questions before we proceed.

- A student is always late for class. Could there be a reasonable excuse for this and, if so, does your system allow for it?

- Students occasionally present summary presentations from other authors, including slides prepared by scholarly authors. How do you interpret that?

- Students sometimes show up for classes and are obviously out of their depth. What do you do? Should they go away and come back later when they’re ready? Do they just need to try harder?

- Students don’t do the pre-reading and try to cram it in just before a session. Is this kind of “just in time” acceptable?

- Students sometimes sit up the back, checking their e-mail, and don’t really want to get involved. Is that ok? What if they do it every time?

- Students are doing a lot of things and often want to shift around deadlines or get you to take into account their work from other courses or outside jobs. Do you allow this? How often? Is there a penalty?

As you can see, I’ve taken each of the original ‘good student’ points and asked you to think about it. Now, let us accept that there are ultimate administrative deadlines (I’ve already talked about this a lot in time banking) and we can accept that the student is aware of these and are not planning to put all their work off until next century.

Now, let’s look at this as it applies to teaching staff. I think we can all agree that a staff member who meets that list are going to achieve a lot of their teaching goals. I’m going to reframe the questions in terms of staff.

- You have to drop your kids off every morning at day care. This means that you show up at your 9am lecture 5 minutes late every day because you physically can’t get there any faster and your partner can’t do it because he/she is working shift work. How do you explain this to your students?

- You are teaching a course from a textbook which has slides prepared already. Is it ok to take these slides and use them without any major modification?

- You’ve been asked to cover another teacher’s courses for two weeks due to their illness. You have a basis in the area but you haven’t had to do anything detailed for it in over 10 years and you’ll also have to give feedback on the final stages of a lengthy assignment. How do you prepare for this and what, if anything, do you tell the class to brief them on your own lack of expertise?

- The staff meeting is coming around and the Head of School wants feedback on a major proposal and discussion at that meeting. You’ve been flat out and haven’t had a chance to look at it, so you skim it on the way to the meeting and take it with you to read in the preliminaries. Given the importance of the proposal, do you think this is a useful approach?

- It’s the same staff meeting and Doctor X is going on (again) about radical pedagogy and Situationist philosophy. You quickly catch up on some important work e-mails and make some meetings for later in the week, while you have a second.

- You’ve got three research papers due, a government grant application and your Head of School needs your workload bid for the next calendar year. The grant deadline is fixed and you’ve already been late for three things for the Head of School. Do you drop one (or more) of the papers or do you write to the convenors to see if you can arrange an extension to the deadline?

Is this artificial? Well, of course, because I’m trying to make a point. Beyond being pedantic on this because you know what I’m saying, if you answered one way for the staff member and other way for the student then you have given the staff member more power in the same situation than the student. Just because we can all sympathise with the staff member (Doctor X sounds horribly familiar, doesn’t he?) doesn’t that the student’s reasons, when explored and contextualised, are not equally valid.

If we are prepared to listen to our students and give their thoughts, reasoning and lives as much weight and value as our own, then rule 0 is most likely not in play at the moment – you don’t think your students are inferior to you. If you thought that the staff member was being perfectly reasonable and yet you couldn’t see why a student should be extended the same privileges, even where I’ve asked you to consider the circumstances where it could be, then it’s possible that the superiority issue is one that has become well-established at your institution.

Ultimately, if this small list is a set of goals, then we should be a reasonable exemplar for our students. Recently, due to illness, I’ve gone from being very reliable in these areas, to being less reliable on things like the level of preparation I used to do and timeliness. I have looked at what I’ve had to do and renegotiated my deadlines, apologising and explaining where I need to. As a result, things are getting done and, as far as I know, most people are happy with what I’m doing. (That’s acceptable but they used to be very happy. I have way to go.) I still have a couple of things to fix, which I haven’t forgotten about, but I’ve had to carry out some triage. I’m honest about this because, that way, I encourage my students to be honest with me. I do what I can, within sound pedagogical framing and our administrative requirements, and my students know that. It makes them think more, become more autonomous and be ready to go out and practice at a higher level, sooner.

This list is quite deliberately constructed but I hope that, within this framework, I’ve made my point: we have to be honest if we are seeing ourselves as superior and, in my opinion, we should work more as equals with each other.

Thoughts on the colonising effect of education.

Posted: November 17, 2014 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, colonisation, community, cultural colonisation, curriculum, education, educational problem, games, higher education, in the student's head, learning, racism, teaching, thinking 2 CommentsThis is going to be longer than usual but these thoughts have been running around in my mind for a while and, rather than break them up, I thought I’d put them all together here. My apologies for the long read but, to help you, here’s the executive summary. Firstly, we’re not going to get anywhere until all of us truly accept that University students are not some sort of different species but that they are actually junior versions of ourselves – not inferior, just less advanced. Secondly, education is heavily colonising but what we often tend to pass on to our students are mechanisms for conformity rather than the important aspects of knowledge, creativity and confidence.

Let me start with some background and look at the primary and secondary schooling system. There is what we often refer to as traditional education: classroom full of students sitting in rows, writing down the words spoken by the person at the front. Assignments test your ability to learn and repeat the words and apply this is well-defined ways to a set of problems. Then we have progressive education that, depending upon your socio-political alignment and philosophical bent, is either a way of engaging students and teachers in the process for better outcomes, more critical thought and a higher degree of creativity; or it is cats and dogs lying down together, panic in the streets, a descent into radicalism and anarchy. (There is, of course, a middle ground, where the cats and dogs sleep in different spots, in rows, but engage in discussions of Foucault.) Dewey wrote on the tension between these two apparatus (seriously, is there anything he didn’t write on?) but, as we know, he was highly opposed to the lining up on students in ranks, like some sort of prison, so let’s examine why.

Simply put, the traditional model is an excellent way to prepare students for factory work but it’s not a great way to prepare them for a job that requires independence or creativity. You sit at your desk, the teacher reads out the instructions, you copy down the instructions, you are assigned piece work to do, you follow the instructions, your work is assessed to determine if it is acceptable, if not, you may have to redo it or it is just rejected. If enough of your work is deemed acceptable, then you are now a successful widget and may take your place in the community. Of course, it will help if your job is very similar to this. However, if your deviation from the norm is towards the unacceptable side then you may not be able to graduate until you conform.

Now, you might be able to argue this on accuracy, were it not for the constraining behavioural overtones in all of this. It’s not about doing the work, it’s about doing the work, quietly, while sitting for long stretches, without complaint and then handing back work that you had no part in defining for someone else to tell you what is acceptable. A pure model of this form cripples independence because there is no scope for independent creation as it must, by definition, deviate and thus be unacceptable.

Progressive models change this. They break up the structure of the classroom, change the way that work is assigned and, in many cases, change the power relationship between student and teacher. The teacher is still authoritative in terms of information but can potentially handle some (controlled for societal reasons) deviation and creativity from their student groups.

The great sad truth of University is that we have a lot more ability to be progressive because we don’t have to worry about too many severe behavioural issues as there is enough traditional education going on below these levels (or too few management resources for children in need) that it is highly unlikely that students with severe behavioural issues will graduate from high school, let alone make it to University with the requisite grades.

But let’s return to the term ‘colonising’, because it is a loaded term. We colonise when we send a group of settlers to a new place and attempt to assert control over it, often implicit in this is the notion that the place we have colonised is now for our own use. Ultimately, those being colonised can fight or they can assimilate. The most likely outcome if the original inhabitants fight is they they are destroyed, if those colonising are technologically superior or greatly outnumber them. Far more likely, and as seen all around the world, is the requirement for the original inhabitants to be assimilated to the now dominant colonist culture. Under assimilation, original cultures shrink to accommodate new rules, requirements, and taboos from the colonists.

In the case of education, students come to a University in order to obtain the benefits of the University culture so they are seeking to be colonised by the rules and values of the University. But it’s very important to realise that any positive colonisation value (and this is a very rare case, it’s worth noting) comes with a large number of negatives. If students come from a non-Western pedagogical tradition, then many requirements at Universities in Australia, the UK and America will be at odds with the way that they have learned previously, whether it’s power distances, collectivism/individualism issues or even in the way that work is going to be assigned and assessed. If students come from a highly traditional educational background, then they will struggle if we break up the desks and expect them to be independent and creative. Their previous experiences define their educational culture and we would expect the same tensions between colonist and coloniser as we would see in any encounter in the past.

I recently purchased a game called “Dog Eat Dog“, which is a game designed to allow you to explore the difficult power dynamics of the colonist/colonised relationship in the Pacific. Liam Burke, the author, is a second-generation half-Filipino who grew up in Hawaii and he developed the game while thinking about his experiences growing up and drawing on other resources from the local Filipino community.

The game is very simple. You have a number of players. One will play the colonist forces (all of them). Each other player will play a native. How do you select the colonist? Well, it’s a simple question: Which player at the table is the richest?

As you can tell, the game starts in uncomfortable territory and, from that point on, it can be very challenging as the the native players will try to run small scenarios that the colonist will continually interrupt, redirect and adjudicate to see how well the natives are playing by the colonist’s rules. And the first rule is:

The (Native people) are inferior to the (Occupation people).

After every scenario, more rules are added and the native population can either conform (for which they are rewarded) or deviate (for which they are punished). It actually lies inside the colonist’s ability to kill all the natives in the first turn, should they wish to do so, because this happened often enough that Burke left it in the rules. At the end of the game, the colonists may be rebuffed but, in order to do that, the natives have become adept at following the rules and this is, of course, at the expense of their own culture.

This is a difficult game to explain in the short form but the PDF is only $10 and I think it’s an important read for just about anyone. It’s a short rule book, with a quick history of Pacific settlement and exemplars, produced from a successful Kickstarter.

Let’s move this into the educational sphere. It would be delightful if I couldn’t say this but, let’s be honest, our entire system is often built upon the premise that:

The students are inferior to the teachers.

Let’s play this out in a traditional model. Every time the students get together in order to do anything, we are there to assess how well they are following the rules. If they behave, they get grades (progress towards graduation). If they don’t conform, then they don’t progress and, because everyone has finite resources, eventually they will drop out, possibly doing something disastrous in the process. (In the original game, the native population can run amok if they are punished too much, which has far too many unpleasant historical precedents.) Every time that we have an encounter with the students, they have to come up with a rule to work out how they can’t make the same mistake again. This new rule is one that they’re judged against.

When I realised how close a parallel this, a very cold shiver went down my spine. But I also realised how much I’d been doing to break out of this system, by treating students as equals with mutual respect, by listening and trying to be more flexible, by interpreting a more rigid pedagogical structure through filters that met everyone’s requirements. But unless I change the system, I am merely one of the “good” overseers on a penal plantation. When the students leave my care, if I know they are being treated badly, I am still culpable.

As I started with, valuing knowledge, accuracy, being productive (in an academic sense), being curious and being creative are all things that we should be passing on from our culture but these are very hard things to pass on with a punishment/reward modality as they are all cognitive in aspect. What is far easier to do is to pass on culture such as sitting silently, being bound by late penalties, conformity to the rules and the worst excesses of the Banking model of education (after Freire) where students are empty receiving objects that we, as teachers, fill up. There is no agency in such a model, nor room for creativity. The jug does not choose the liquid that fills it.

It is easy to see examples all around us of the level of disrespect levelled at colonised peoples, from the mindless (and well-repudiated) nonsense spouted in Australian newspapers about Aboriginal people to the racist stereotyping that persists despite the overwhelming evidence of equality between races and genders. It is also as easy to see how badly students can be treated by some staff. When we write off a group of students because they are ‘bad students’ then we have made them part of a group that we don’t respect – and this empowers us to not have to treat them as well as we treat ourselves.

We have to start from the basic premise that our students are at University because they want to be like us, but like the admirable parts of us, not the conformist, factory model, industrial revolution prison aspects. They are junior lawyers, young engineers, apprentice architects when they come to us – they do not have to prove their humanity in order to be treated with respect. However, this does have to be mutual and it’s important to reflect upon the role that we have as a mentor, someone who has greater knowledge in an area and can share it with a more junior associate to bring them up to the same level one day.

If we regard students as being worthy of respect, as being potential peers, then we are more likely to treat them with a respect that engenders a reciprocal relationship. Treat your students like idiots and we all know how that goes.

The colonial mindset is poisonous because of the inherent superiority and because of the value of conformity to imposed rules above the potential to be gained from incorporating new and useful aspects of other cultures. There are many positive aspects of University culture but they can happily coexist with other educational traditions and cultures – the New Zealand higher educational system is making great steps in this direction to be able to respect both Maori tradition and the desire of young people to work in a westernised society without compromising their traditions.

We have to start from the premise that all people are equal, because to do otherwise is to make people unequal. We then must regard our students as ourselves, just younger, less experienced and only slightly less occasionally confused than we were at that age. We must carefully examine how we expose students to our important cultural aspects and decide what is and what is not important. However, if all we turn out at the end of a 3-4 year degree is someone who can perform a better model of piece work and is too heavily intimidated into conformity that they cannot do anything else – then we have failed our students and ourselves.

The game I mentioned, “Dog Eat Dog”, starts with a quote by a R. Zamora Linmark from his poem “They Like You Because You Eat Dog”. Linmark is a Filipino American poet, novelist, and playwright, who was educated in Honolulu. His challenging poem talks about the ways that a second-class citizenry are racially classified with positive and negative aspects (the exoticism is balanced against a ‘brutish’ sexuality, for example) but finishes with something that is even more challenging. Even when a native population fully assimilates, it is never enough for the coloniser, because they are still not quite them.

“They like you because you’re a copycat, want to be just like them. They like you because—give it a few more years—you’ll be just like them.

And when that time comes, will they like you more?”R. Zamora Linmark, “They Like You Because You Eat Dog”, from “Rolling the R’s”

I had a discussion once with a remote colleague who said that he was worried the graduates of his own institution weren’t his first choice to supervise for PhDs as they weren’t good enough. I wonder whose fault he thought that was?

CodeSpells! A Kickstarter to make a difference. @sesperu @codespells #codespells

Posted: September 9, 2014 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, blockly, blogging, Code Spells, codespells, community, education, educational problem, educational research, games, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, resources, Sarah Esper, Stephen Foster, student perspective, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, UCSD, universal principles of design Leave a commentI first met Sarah Esper a few years ago when she was demonstrating the earlier work in her PhD project with Stephen Foster on CodeSpells, a game-based project to start kids coding. In a pretty enjoyable fantasy game environment, you’d code up spells to make things happen and, along the way, learn a lot about coding. Their team has grown and things have come a long way since then for CodeSpells, and they’re trying to take it from its research roots into something that can be used to teach coding on a much larger scale. They now have a Kickstarter out, which I’m backing (full disclosure), to get the funds they need to take things to that next level.

Teaching kids to code is hard. Teaching adults to code can be harder. There’s a big divide these days between the role of user and creator in the computing world and, while we have growing literary in use, we still have a long way to go to get more and more people creating. The future will be programmed and it is, honestly, a new form of literacy that our children will benefit from.

If you’re one of my readers who likes the idea of new approaches to education, check this out. If you’re an old-timey Multi-User Dungeon/Shared Hallucination person like me, this is the creative stuff we used to be able to do on-line, but for everyone and with cool graphics in a multi-player setting. If you have kids, and you like the idea of them participating fully in the digital future, please check this out.

To borrow heavily from their page, 60% of jobs in science, technology,engineering and maths are computing jobs but AP Computer Science is only taught at 5% of schools. We have a giant shortfall of software people coming up and this will be an ugly crash when it comes because all of the nice things we have become used to in the computing side will slow down and, in some cases, pretty much stop. Invest in the future!

I have no connection to the project apart from being a huge supporter of Sarah’s drive and vision and someone who would really like to see this project succeed. Please go and check it out!

Enemies, Friends and Frenemies: Distance, Categorisation and Fun.

Posted: January 29, 2014 Filed under: Education | Tags: curriculum, data visualisation, design, education, educational problem, games, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools Leave a commentAs Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola wrote in “The Godfather Part II”:

… keep your friends close but your enemies closer.

(I bet you thought that was Sun Tzu, the author of “The Art of War”. So did I but this movie is the first use.)

I was thinking about this the other day and it occurred to me that this is actually a simple modelling problem. Can I build a model which will show the space around me and where I would expect to find friends and enemies? Of course, you might be wondering “why would you do this?” Well, mostly because it’s a little bit silly and it’s a way of thinking that has some fun attached to it. When I ask students to build models of the real world, where they think about how they would represent all of the important aspects of the problem and how they would simulate the important behaviours and actions seen with it, I often give them mathematical or engineering applications. So why not something a little more whimsical?

From looking at the quote, we would assume that there is some distance around us (let’s call it a circle) where we find everyone when they come up to talk to us, friend or foe, and let’s also assume that the elements “close” and “closer” refer to how close we let them get in conversation. (Other interpretations would have us living in a neighbourhood of people who hate us, while we have to drive to a different street to sit down for dinner with people who like us.) So all of our friends and enemies are in this circle, but enemies will be closer. That looks like this:

So now we have a visual model of what is going on and, if we wanted to, we could build a simple program that says something like “if you’re in this zone, then you’re an enemy, but if you’re in that zone then you’re a friend” where we define the zones in terms of nested circular regions. But, as we know, friend always has your back and enemies stab you in the back, so now we need to add something to that “ME” in the middle – a notion of which way I’m facing – and make sure that I can always see my enemies. Let’s make the direction I’m looking an arrow. (If I could draw better, I’d put glasses on the front. If you’re doing this in the classroom, an actual 3D dummy head shows position really well.) That looks like this:

Now our program has to keep track of which way we’re facing and then it checks the zones, on the understanding that either we’re going to arrange things to turn around if an enemy is behind us, or we can somehow get our enemies to move (possibly by asking nicely). This kind of exercise can easily be carried out by students and it raises all sorts of questions. Do I need all of my enemies to be closer than my friends or is it ok if the closest person to me is an enemy? What happens if my enemies are spread out in a triangle around me? Is they won’t move, do I need to keep rotating to keep an eye on them or is it ok if I stand so that they get as much of my back as they can? What is an acceptable solution to this problem? You might be surprised how much variation students will suggest in possible solutions, as they tell you what makes perfect sense to them for this problem.

When we do this kind of thing with real problems, we are trying to specify the problem to a degree that we remove all of the unasked questions that would otherwise make the problem ambiguous. Of course, even the best specification can stumble if you introduce new information. Some of you will have heard of the term ‘frenemy’, which apparently:

can refer to either an enemy pretending to be a friend or someone who really is a friend but is also a rival (from Wikipedia and around since 1953, amazingly!)

What happens if frenemies come into the mix? Well, in either case, we probably want to treat them like an enemy. If they’re an enemy pretending to be a friend, and we know this, then we don’t turn our back on them and, even in academia, it’s never all that wise to turn your back on a rival, either. (Duelling citations at dawn can be messy.) In terms of our simple model, we can deal with extending the model because we clearly understand what the important aspects are of this very simple situation. It would get trickier if frenemies weren’t clearly enemies and we would have to add more rules to our model to deal with this new group.

This can be played out with students of a variety of ages, across a variety of curricula, with materials as simple as a board, a marker and some checkers. Yet this is a powerful way to explain models, specification and improvement, without having to write a single line of actual computer code or talk about mathematics or bridges! I hope you found it useful.

A Break in the Silence: Time to Tell a Story

Posted: December 30, 2013 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, design, education, feedback, games, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, resources, storytelling, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, work/life balance, workload 2 CommentsIt has been a while since I last posted here but that is a natural outcome of focusing my efforts elsewhere – at some stage I had to work out what I had time to do and do it. I always tell my students to cut down to what they need to do and, once I realised that the time I was spending on the blog was having one of the most significant impacts on my ability to juggle everything else, I had to eat my own dogfood and cut back on the blog.

Of course, I didn’t do it correctly because instead of cutting back, I completely cut it out. Not quite what I intended but here’s another really useful piece of information: if you decide to change something then clearly work out how you are going to change things to achieve your goal. Which means, ahem, working out what your goals are first.

I’ve done a lot of interesting stuff over the last 6 months, and there are more to come, which means that I do have things to write about but I shall try and write about one a week as a minimum, rather than one per day. This is a pace that I hope to keep up and one that will mean that more of you will read more of what I write, rather than dreading the daily kiloword delivery.

I’ll briefly reflect here on some interesting work and seminars I’ve been looking at on business storytelling – taking a personal story, something authentic, and using it to emphasise a change in business behaviour or to emphasise a characteristic. I recently attended one of the (now defunct) One Thousand and One’s short seminars on engaging people with storytelling. (I’m reading their book “Hooked” at the moment. It’s quite interesting and refers to other interesting concepts as well.) I realise that such ideas, along with many of my notions of design paired with content, will have a number of readers peering at the screen and preparing a retort along the lines of “Storytelling? STORYTELLING??? Whatever happened to facts?”

Why storytelling? Because bald facts sometimes just don’t work. Without context, without a way to integrate information into existing knowledge and, more importantly, without some sort of established informational relationship, many people will ignore facts unless we do more work than just present them.

How many examples do you want: Climate Change, Vaccination, 9/11. All of these have heavily weighted bodies of scientific evidence that states what the answer should be, and yet there is powerful and persistent opposition based, largely, on myth and storytelling.

Education has moved beyond the rationing out of approved knowledge from the knowledge rich to those who have less. The tyrannical informational asymmetry of the single text book, doled out in dribs and drabs through recitation and slow scrawling at the front of the classroom, looks faintly ludicrous when anyone can download most of the resources immediately. And yet, as always, owning the book doesn’t necessarily teach you anything and it is the educator’s role as contextualiser, framer, deliverer, sounding board and value enhancer that survives the death of the drip-feed and the opening of the flood gates of knowledge. To think that storytelling is the delivery of fairytales, and that is all it can be, is to sell such a useful technique short.

To use storytelling educationally, however, we need to be focused on being more than just entertaining or engaging. Borrowing heavily from “Hooked”, we need to have a purpose in telling the story, it needs to be supported by data and it needs to be authentic. In my case, I have often shared stories of my time in working with computer networks, in short bursts, to emphasise why certain parts of computer networking are interesting or essential (purpose), I provide enough information to show this is generally the case (data) and because I’m talking about my own experiences, they ring true (authenticity).

If facts alone could sway humanity, we would have adopted Dewey’s ideas in the 1930s, instead of rediscovering the same truths decade after decade. If only the unembellished truth mattered, then our legal system would look very, very different. Our students are surrounded by talented storytellers and, where appropriate, I think those ranks should include us.

Now, I have to keep to the commitment I made 8 months ago, that I would never turn down the chance to have one of my cats on my lap when they wanted to jump up, and I wish you a very happy new year if I don’t post beforehand.

Skill Games versus Money Games: Disguising One Game As Another

Posted: July 5, 2013 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, games, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, plagiarism, principles of design, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design Leave a commentI recently ran across a very interesting article on Gamasutra on the top tips for turning a Free To Play (F2P) game into a Paying game by taking advantage of the way that humans think and act. F2P games are quite common but, obviously, it costs money to make a game so there has to be some sort of associated revenue stream. In some cases, the F2P is a Lite version of the pay version, so after being hooked you go and buy the real thing. Sometimes there is an associated advertising stream, where you viewing the ads earns the producer enough money to cover costs. However, these simple approaches pale into insignificance when compared with the top tips in the link.

Ramin identifies two games for this discussion: games of skill, where it is your ability to make sound decisions that determines the outcome, and money games, where your success is determined by the amount of money you can spend. Games of chance aren’t covered here but, given that we’re talking about motivation and agency, we’re depending upon one specific blindspot (the inability of humans to deal sensibly with probability) rather than the range of issues identified in the article.

I dont want to rehash the entire article but the key points that I want to discuss are the notion of manipulating difficulty and fun pain. A game of skill is effectively fun until it becomes too hard. If you want people to keep playing then you have to juggle the difficulty enough to make it challenging but not so hard that you stop playing. Even where you pay for a game up front, a single payment to play, you still want to get enough value out of it – too easy and you finish too quickly and feel that you’ve wasted your money; too hard and you give up in disgust, again convinced that you’ve wasted your money. Ultimately, in a pure game of skill, difficulty manipulation must be carefully considered. As the difficulty ramps up, the player is made uncomfortable, the delightful term fun pain is applied here, and resolving the difficulty removes this.

Or, you can just pay to make the problem go away. Suddenly your game of skill has two possible modes of resolution: play through increasing difficulty, at some level of discomfort or personal inconvenience, or, when things get hard enough, pump in a deceptively small amount of money to remove the obstacle. The secret of the P2P game that becomes successfully monetised is that it was always about the money in the first place and the initial rounds of the game were just enough to get you engaged to a point where you now have to pay in order to go further.

You can probably see where I’m going with this. While it would be trite to describe education as a game of skill, it is most definitely the most apt of the different games on offer. Progress in your studies should be a reflection of invested time in study, application and the time spent in developing ideas: not based on being ‘lucky’, so the random game isn’t a choice. The entire notion of public education is founded on the principle that educational opportunities are open to all. So why do some parts of this ‘game’ feel like we’ve snuck in some covert monetisation?

I’m not talking about fees, here, because that’s holding the place of the fee you pay to buy a game in the first place. You all pay the same fee and you then get the same opportunities – in theory, what comes out is based on what the student then puts in as the only variable.

But what about textbooks? Unless the fee we charge automatically, and unavoidably, includes the cost of the textbook, we have now broken the game into two pieces: the entry fee and an ‘upgrade’. What about photocopying costs? Field trips? A laptop computer? An iPad? Home internet? Bus fare?