Large Scale Authenticity: What I Learned About MOOCs from Reality Television

Posted: March 8, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, design, education, ethics, feedback, games, higher education, MKR, moocs, My Kitchen Rules, principles of design, reflection, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking 1 CommentThe development of social media platforms has allows us to exchange information and, well, rubbish very easily. Whether it’s the discussion component of a learning management system, Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Snapchat or whatever will be the next big thing, we can now chat to each other in real time very, very easily.

One of the problems with any on-line course is trying to maintain a community across people who are not in the same timezone, country or context. What we’d really like is for the community communication to come from the students, with guidance and scaffolding from the lecturing staff, but sometimes there’s priming, leading and… prodding. These “other” messages have to be carefully crafted and they have to connect with the students or they risk being worse than no message at all. As an example, I signed up for an on-line course and then wasn’t able to do much in the first week. I was sitting down to work on it over the weekend when a mail message came in from the organisers on the community board congratulating me on my excellent progress on things I hadn’t done. (This wasn’t isolated. The next year, despite not having signed up, the same course sent me even more congratulations on totally non-existent progress.) This sends the usual clear messages that we expect from false praise and inauthentic communication: the student doesn’t believe that you know them, they don’t feel part of an authentic community and they may disengage. We have, very effectively, sabotaged everything that we actually wanted to build.

Let’s change focus. For a while, I was watching a show called “My Kitchen Rules” on local television. It pretends to be about cooking (with competitive scoring) but it’s really about flogging products from a certain supermarket while delivering false drama in the presence of dangerously orange chefs. An engineered activity to ensure that you replace an authentic experience with consumerism and commodities? Paging Guy Debord on the Situationist courtesy phone: we have a Spectacle in progress. What makes the show interesting is the associated Twitter feed, where large numbers of people drop in on the #mkr to talk about the food, discuss the false drama, exchange jokes and develop community memes, such as sharing pet pictures with each other over the (many) ad breaks. It’s a community. Not everyone is there for the same reasons: some are there to be rude about people, some are actually there for the cooking (??) and some are… confused. But the involvement in the conversation, interplay and development of a shared reality is very real.

And this would all be great except for one thing: Australia is a big country and spans a lot of timezones. My Kitchen Rules is broadcast at 7:30pm, starting in Melbourne, Canberra, Tasmania and Sydney, then 30 minutes later in Adelaide, then 30 minutes later again in Queensland (they don’t do daylight savings), then later again for Perth. So now we have four different time groups to manage, all watching the same show.

But the Twitter feed starts on the first time point, Adelaide picks up discussions from the middle of the show as they’re starting and then gets discussions on scores as the first half completes for them… and this is repeated for Queensland viewers and then for Perth. Now , in the community itself, people go on and off the feed as their version of the show starts and stops and, personally, I don’t find score discussions very distracting because I’m far more interested in the Situation being created in the Twitter stream.

Enter the “false tweets” of the official MKR Social Media team who ask questions that only make sense in the leading timezone. Suddenly, everyone who is not quite at the same point is then reminded that we are not in the same place. What does everyone think of the scores? I don’t know, we haven’t seen it yet. What’s worse are the relatively lame questions that are being asked in the middle of an actual discussion that smell of sponsorship involvement or an attempt to produce the small number of “acceptable” tweets that are then shared back on the TV screen for non-connected viewers. That’s another thing – everyone outside of the first timezone has very little chance of getting their Tweet displayed. Imagine if you ran a global MOOC where only the work of the students in San Francisco got put up as an example of good work!

This is a great example of an attempt to communicate that fails dismally because it doesn’t take into account how people are using the communications channel, isn’t inclusive (dismally so) and constantly reminds people who don’t live in a certain area that they really aren’t being considered by the program’s producers.

You know what would fix it? Putting it on at the same time everywhere but that, of course, is tricky because of the way that advertising is sold and also because it would force poor Perth to start watching dinner television just after work!

But this is a very important warning of what happens when you don’t think about how you’ve combined the elements of your environment. It’s difficult to do properly but it’s terrible when done badly. And I don’t need to go and enrol in a course to show you this – I can just watch a rather silly cooking show.

Why “#thedress” is the perfect perception tester.

Posted: March 2, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, Avant garde, collaboration, community, Dada, data visualisation, design, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, Kazimir Malevich, learning, Marcel Duchamp, modern art, principles of design, readymades, reflection, resources, Russia, Stalin, student perspective, Suprematism, teaching, thedress, thinking 1 CommentI know, you’re all over the dress. You’ve moved on to (checks Twitter) “#HouseOfCards”, Boris Nemtsov and the new Samsung gadgets. I wanted to touch on some of the things I mentioned in yesterday’s post and why that dress picture was so useful.

The first reason is that issues of conflict caused by different perception are not new. You only have to look at the furore surrounding the introduction of Impressionism, the scandal of the colour palette of the Fauvists, the outrage over Marcel Duchamp’s readymades and Dada in general, to see that art is an area that is constantly generating debate and argument over what is, and what is not, art. One of the biggest changes has been the move away from representative art to abstract art, mainly because we are no longer capable of making the simple objective comparison of “that painting looks like the thing that it’s a painting of.” (Let’s not even start on the ongoing linguistic violence over ending sentences with prepositions.)

Once we move art into the abstract, suddenly we are asking a question beyond “does it look like something?” and move into the realm of “does it remind us of something?”, “does it make us feel something?” and “does it make us think about the original object in a different way?” You don’t have to go all the way to using body fluids and live otters in performance pieces to start running into the refrains so often heard in art galleries: “I don’t get it”, “I could have done that”, “It’s all a con”, “It doesn’t look like anything” and “I don’t like it.”

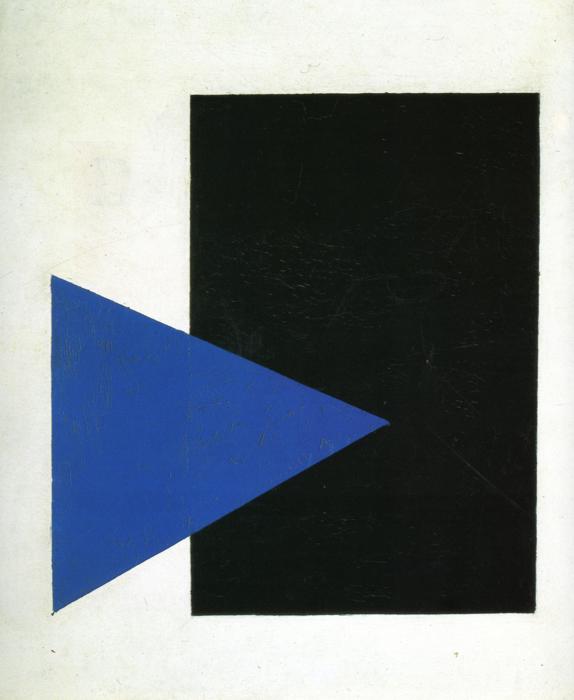

This was a radical departure from art of the time, part of the Suprematism movement that flourished briefly before Stalin suppressed it, heavily and brutally. Art like this was considered subversive, dangerous and a real threat to the morality of the citizenry. Not bad for two simple shapes, is it? And, yet, many people will look at this and use of the above phrases. There is an enormous range of perception on this very simple (yet deeply complicated) piece of art.

The viewer is, of course, completely entitled to their subjective opinion on art but this is, for many cases, a perceptual issue caused by a lack of familiarity with the intentions, practices and goals of abstract art. When we were still painting pictures of houses and rich people, there were many pictures from the 16th to 18th century which contain really badly painted animals. It’s worth going to an historical art museum just to look at all the crap animals. Looking at early European artists trying to capture Australian fauna gives you the same experience – people weren’t painting what they were seeing, they were painting a reasonable approximation of the representation and putting that into the picture. Yet this was accepted and it was accepted because it was a commonly held perception. This also explains offensive (and totally unrealistic) caricatures along racial, gender or religious lines: you accept the stereotype as a reasonable portrayal because of shared perception. (And, no, I’m not putting pictures of that up.)

But, when we talk about art or food, it’s easy to get caught up in things like cultural capital, the assets we have that aren’t money but allow us to be more socially mobile. “Knowing” about art, wine or food has real weight in certain social situations, so the background here matters. Thus, to illustrate that two people can look at the same abstract piece and have one be enraptured while the other wants their money back is not a clean perceptual distinction, free of outside influence. We can’t say “human perception is very a personal business” based on this alone because there are too many arguments to be made about prior knowledge, art appreciation, socioeconomic factors and cultural capital.

But let’s look at another argument starter, the dreaded Monty Hall Problem, where there are three doors, a good prize behind one, and you have to pick a door to try and win a prize. If the host opens a door showing you where the prize isn’t, do you switch or not? (The correctly formulated problem is designed so that switching is the right thing to do but, again, so much argument.) This is, again, a perceptual issue because of how people think about probability and how much weight they invest in their decision making process, how they feel when discussing it and so on. I’ve seen people get into serious arguments about this and this doesn’t even scratch the surface of the incredible abuse Marilyn vos Savant suffered when she had the audacity to post the correct solution to the problem.

This is another great example of what happens when the human perceptual system, environmental factors and facts get jammed together but… it’s also not clean because you can start talking about previous mathematical experience, logical thinking approaches, textual analysis and so on. It’s easy to say that “ah, this isn’t just a human perceptual thing, it’s everything else.”

This is why I love that stupid dress picture. You don’t need to have any prior knowledge of art, cultural capital, mathematical background, history of game shows or whatever. All you need are eyes and relatively functional colour sense of colour. (The dress doesn’t even hit most of the colour blindness issues, interestingly.)

The dress is the clearest example we have that two people can look at the same thing and it’s perception issues that are inbuilt and beyond their control that cause them to have a difference of opinion. We finally have a universal example of how being human is not being sure of the world that we live in and one that we can reproduce anytime we want, without having to carry out any more preparation than “have you seen this dress?”

What we do with it is, as always, the important question now. For me, it’s a reminder to think about issues of perception before I explode with rage across the Internet. Some things will still just be dumb, cruel or evil – the dress won’t heal the world but it does give us a new filter to apply. But it’s simple and clean, and that’s why I think the dress is one of the best things to happen recently to help to bring us together in our discussions so that we can sort out important things and get them done.

Is this a dress thing? #thedress

Posted: March 1, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, blue and black dress, colour palette, community, data visualisation, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, higher education, improving perception, learning, Leonard Nimoy, llap, measurement, perception, perceptual system, principles of design, teaching, teaching approaches, thedress, thinking 1 CommentFor those who missed it, the Internet recently went crazy over llamas and a dress. (If this is the only thing that survives our civilisation, boy, is that sentence going to confuse future anthropologists.) Llamas are cool (there ain’t no karma drama with a llama) so I’m going to talk about the dress. This dress (with handy RGB codes thrown in, from a Wired article I’m about to link to):

When I first saw it, and I saw it early on, the poster was asking what colour it was because she’d taken a picture in the store of a blue and black dress and, yet, in the picture she took, it sometimes looked white and gold and it sometimes looked blue and black. The dress itself is not what I’m discussing here today.

Let’s get something out of the way. Here’s the Wired article to explain why two different humans can see this dress as two different colours and be right. Okay? The fact is that the dress that the picture is of is a blue and black dress (which is currently selling like hot cakes, by the way) but the picture itself is, accidentally, a picture that can be interpreted in different ways because of how our visual perception system works.

This isn’t a hoax. There aren’t two images (or more). This isn’t some elaborate Alternative Reality Game prank.

But the reaction to the dress itself was staggering. In between other things, I plunged into a variety of different social fora to observe the reaction. (Other people also noticed this and have written great articles, including this one in The Atlantic. Thanks for the link, Marc!) The reactions included:

- Genuine bewilderment on the part of people who had already seen both on the same device at nearly adjacent times and were wondering if they were going mad.

- Fierce tribalism from the “white and gold” and “black and blue” camps, within families, across social groups as people were convinced that the other people were wrong.

- People who were sure that it was some sort of elaborate hoax with two images. (No doubt, Big Dress was trying to cover something up.)

- Bordering-on-smug explanations from people who believed that seeing it a certain way indicated that they had superior “something or other”, where you can put day vision/night vision/visual acuity/colour sense/dressmaking skill/pixel awareness/photoshop knowledge.

- People who thought it was interesting and wondered what was happening.

- Attention policing from people who wanted all of social media to stop talking about the dress because we should be talking about (insert one or more) llamas, Leonard Nimoy (RIP, LLAP, \\//) or the disturbingly short lifespan of Russian politicians.

The issue to take away, and the reason I’ve put this on my education blog, is that we have just had an incredibly important lesson in human behavioural patterns. The (angry) team formation. The presumption that someone is trying to make us feel stupid, playing a prank on us. The inability to recognise that the human perceptual system is, before we put any actual cognitive biases in place, incredibly and profoundly affected by the processing shortcuts our perpetual systems take to give us a view of the world.

I want to add a new question to all of our on-line discussion: is this a dress thing?

There are matters that are not the province of simple perceptual confusion. Human rights, equality, murder, are only three things that do not fall into the realm of “I don’t quite see what you see”. Some things become true if we hold the belief – if you believe that students from background X won’t do well then, weirdly enough, then they don’t do well. But there are areas in education when people can see the same things but interpret them in different ways because of contextual differences. Education researchers are well aware that a great deal of what we see and remember about school is often not how we learned but how we were taught. Someone who claims that traditional one-to-many lecturing, as the only approach, worked for them, when prodded, will often talk about the hours spent in the library or with study groups to develop their understanding.

When you work in education research, you get used to people effectively calling you a liar to your face because a great deal of our research says that what we have been doing is actually not a very good way to proceed. But when we talk about improving things, we are not saying that current practitioners suck, we are saying that we believe that we have evidence and practice to help everyone to get better in creating and being part of learning environments. However, many people feel threatened by the promise of better, because it means that they have to accept that their current practice is, therefore, capable of improvement and this is not a great climate in which to think, even to yourself, “maybe I should have been doing better”. Fear. Frustration. Concern over the future. Worry about being in a job. Constant threats to education. It’s no wonder that the two sides who could be helping each other, educational researchers and educational practitioners, can look at the same situation and take away both a promise of a better future and a threat to their livelihood. This is, most profoundly, a dress thing in the majority of cases. In this case, the perceptual system of the researchers has been influenced by research on effective practice, collaboration, cognitive biases and the operation of memory and cognitive systems. Experiment after experiment, with mountains of very cautious, patient and serious analysis to see what can and can’t be learnt from what has been done. This shows the world in a different colour palette and I will go out on a limb and say that there are additional colours in their palette, not just different shades of existing elements. The perceptual system of other people is shaped by their environment and how they have perceived their workplace, students, student behaviour and the personalisation and cognitive aspects that go with this. But the human mind takes shortcuts. Makes assumptions. Has biasses. Fills in gaps to match the existing model and ignores other data. We know about this because research has been done on all of this, too.

You look at the same thing and the way your mind works shapes how you perceive it. Someone else sees it differently, You can’t understand each other. It’s worth asking, before we deploy crushing retorts in electronic media, “is this a dress thing?”

The problem we have is exactly as we saw from the dress: how we address the situation where both sides are convinced that they are right and, from a perceptual and contextual standpoint, they are. We are now in the “post Dress” phase where people are saying things like “Oh God, that dress thing. I never got the big deal” whether they got it or not (because the fad is over and disowning an old fad is as faddish as a fad) and, more reflectively, “Why did people get so angry about this?”

At no point was arguing about the dress colour going to change what people saw until a certain element in their perceptual system changed what it was doing and then, often to their surprise and horror, they saw the other dress! (It’s a bit H.P. Lovecraft, really.) So we then had to work out how we could see the same thing and both be right, then talk about what the colour of the dress that was represented by that image was. I guarantee that there are people out in the world still who are convinced that there is a secret white and gold dress out there and that they were shown a picture of that. Once you accept the existence of these people, you start to realise why so many Internet arguments end up descending into the ALL CAPS EXCHANGE OF BALLISTIC SENTENCES as not accepting that what we personally perceive as being the truth could not be universally perceived is one of the biggest causes of argument. And we’ve all done it. Me, included. But I try to stop myself before I do it too often, or at all.

We have just had a small and bloodless war across the Internet. Two teams have seized the same flag and had a fierce conflict based on the fact that the other team just doesn’t get how wrong they are. We don’t want people to be bewildered about which way to go. We don’t want to stay at loggerheads and avoid discussion. We don’t want to baffle people into thinking that they’re being fooled or be condescending.

What we want is for people to recognise when they might be looking at what is, mostly, a perceptual problem and then go “Oh” and see if they can reestablish context. It won’t always work. Some people choose to argue in bad faith. Some people just have a bee in their bonnet about some things.

“Is this a dress thing?”

In amongst the llamas and the Vulcans and the assassination of Russian politicians, something that was probably almost as important happened. We all learned that we can be both wrong and right in our perception but it is the way that we handle the situation that truly determines whether we’re handling the situation in the wrong or right way. I’ve decided to take a two week break from Facebook to let all of the latent anger that this stirred up die down, because I think we’re going to see this venting for some time.

Maybe you disagree with what I’ve written. That’s fine but, first, ask yourself “Is this a dress thing?”

Live long and prosper.

When Does Collaborative Work Fall Into This Trap?

Posted: September 11, 2014 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, collaboration, community, crowdsourcing, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, interested parties, learning, principles of design, student perspective, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, universal principles of design, University of Southampton, Victor Naroditskiy Leave a commentA recent study has shown that crowdsourcing activities are prone to bringing out the competitors’ worst competitive instincts.

“[T]he openness makes crowdsourcing solutions vulnerable to malicious behaviour of other interested parties,” said one of the study’s authors, Victor Naroditskiy from the University of Southampton, in a release on the study. “Malicious behaviour can take many forms, ranging from sabotaging problem progress to submitting misinformation. This comes to the front in crowdsourcing contests where a single winner takes the prize.” (emphasis mine)

You can read more about it here but it’s not a pretty story. Looks like a pretty good reason to be very careful about how we construct competitive challenges in the classroom!

CodeSpells! A Kickstarter to make a difference. @sesperu @codespells #codespells

Posted: September 9, 2014 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, blockly, blogging, Code Spells, codespells, community, education, educational problem, educational research, games, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, resources, Sarah Esper, Stephen Foster, student perspective, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, UCSD, universal principles of design Leave a commentI first met Sarah Esper a few years ago when she was demonstrating the earlier work in her PhD project with Stephen Foster on CodeSpells, a game-based project to start kids coding. In a pretty enjoyable fantasy game environment, you’d code up spells to make things happen and, along the way, learn a lot about coding. Their team has grown and things have come a long way since then for CodeSpells, and they’re trying to take it from its research roots into something that can be used to teach coding on a much larger scale. They now have a Kickstarter out, which I’m backing (full disclosure), to get the funds they need to take things to that next level.

Teaching kids to code is hard. Teaching adults to code can be harder. There’s a big divide these days between the role of user and creator in the computing world and, while we have growing literary in use, we still have a long way to go to get more and more people creating. The future will be programmed and it is, honestly, a new form of literacy that our children will benefit from.

If you’re one of my readers who likes the idea of new approaches to education, check this out. If you’re an old-timey Multi-User Dungeon/Shared Hallucination person like me, this is the creative stuff we used to be able to do on-line, but for everyone and with cool graphics in a multi-player setting. If you have kids, and you like the idea of them participating fully in the digital future, please check this out.

To borrow heavily from their page, 60% of jobs in science, technology,engineering and maths are computing jobs but AP Computer Science is only taught at 5% of schools. We have a giant shortfall of software people coming up and this will be an ugly crash when it comes because all of the nice things we have become used to in the computing side will slow down and, in some cases, pretty much stop. Invest in the future!

I have no connection to the project apart from being a huge supporter of Sarah’s drive and vision and someone who would really like to see this project succeed. Please go and check it out!

Talking Ethics with the Terminator: Using Existing Student Experience to Drive Discussion

Posted: September 5, 2014 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, ethical issues, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentOne of the big focuses at our University is the Small-Group Discovery Experience, an initiative from our overall strategy document, the Beacon of Enlightenment. You can read all of the details here, but the essence is that a small group of students and an experienced research academic meet regularly to start the students down the path of research, picking up skills in an active learning environment. In our school, I’ve run it twice as part of the professional ethics program. This second time around, I think it’s worth sharing what we did, as it seems to be working well.

Why ethics? Well, this is first year and it’s not all that easy to do research into Computing if you don’t have much foundation, but professional skills are part of our degree program so we looked at an exploration of ethics to build a foundation. We cover ethics in more detail in second and third year but it’s basically a quick “and this is ethics” lecture in first year that doesn’t give our students much room to explore the detail and, like many of the more intellectual topics we deal with, ethical understanding comes from contemplation and discussion – unless we just want to try to jam a badly fitting moral compass on to everyone and be done.

Ethical issues present the best way to talk about the area as an introduction as much of the formal terminology can be quite intimidating for students who regard themselves as CS majors or Engineers first, and may not even contemplate their role as moral philosophers. But real-world situations where ethical practice is more illuminating are often quite depressing and, from experience, sessions in medical ethics, and similar, rapidly close down discussion because it can be very upsetting. We took a different approach.

The essence of any good narrative is the tension that is generated from the conflict it contains and, in stories that revolve around artificial intelligence, robots and computers, this tension often comes from what are fundamentally ethical issues: the machine kills, the computer goes mad, the AI takes over the world. We decided to ask the students to find two works of fiction, from movies, TV shows, books and games, to look into the ethical situations contained in anything involving computers, AI and robots. Then we provided them with a short suggested list of 20 books and 20 movies to start from and let them go. Further guidance asked them to look into the active ethical agents in the story – who was doing what and what were the ethical issues?

I saw the students after they had submitted their two short paragraphs on this and I was absolutely blown out of the water by their informed, passionate and, above all, thoughtful answers to the questions. Debate kept breaking out on subtle points. The potted summary of ethics that I had given them (follow the rules, aim for good outcomes or be a good person – sorry, ethicists) provided enough detail for the students to identify issues in rule-based approaches, utilitarianism and virtue ethics, but I could then introduce terms to label what they had already done, as they were thinking about them.

I had 13 sessions with a total of 250 students and it was the most enjoyable teaching experience I’ve had all year. As follow-up, I asked the students to enter all of their thoughts on their entities of choice by rating their autonomy (freedom to act), responsibility (how much we could hold them to account) and perceived humanity, using a couple of examples to motivate a ranking system of 0-5. A toddler is completely free to act (5) and completely human (5) but can’t really be held responsible for much (0-1 depending on the toddler). An aircraft autopilot has no humanity or responsibility but it is completely autonomous when actually flying the plane – although it will disengage when things get too hard. A soldier obeying orders has an autonomy around 5. Keanu Reeves in the Matrix has a humanity of 4. At best.

They’ve now filled the database up with their thoughts and next week we’re going to discuss all of their 0-5 ratings as small groups, then place them on a giant timeline of achievements in literature, technology, AI and also listing major events such as wars, to see if we can explain why authors presented the work that they did. When did we start to regard machines as potentially human and what did the world seem like them to people who were there?

This was a lot of fun and, while it’s taken a little bit of setting up, this framework works well because students have seen quite a lot, the trick is just getting to think about with our ethical lens. Highly recommended.

ITiCSE 2014, Day 3, Session 6A, “Digital Fluency”, #ITiCSE2014 #ITiCSE

Posted: June 25, 2014 Filed under: Education | Tags: ALICE, arm the princess, Bologna model, competency, competency-based assessment, computational thinking, computer science education, Duke, education, educational problem, educational research, empowering minorities, empowering women, higher education, ITiCSE, ITiCSE 2014, key competencies, learning, middle school, non-normative approaches, pattern analysis, principles of design, reflection, teaching, thinking, tools, women in computing Leave a commentThe first paper was “A Methodological Approach to Key Competences in Informatics”, presented by Christina Dörge. The motivation for this study is moving educational standards from input-oriented approaches to output-oriented approaches – how students will use what you teach them in later life. Key competencies are important but what are they? What are the definitions, terms and real meaning of the words “key competencies”? A certificate of a certain grade or qualification doesn’t actually reflect true competency is many regards. (Bologna focuses on competencies but what do really mean?) Competencies also vary across different disciplines as skills are used differently in different areas – can we develop a non-normative approach to this?

The author discussed Qualitative Content Analysis (QCA) to look at different educational methods in the German educational system: hardware-oriented approaches, algorithm-oriented, application-oriented, user-oriented, information-oriented and, finally, system-oriented. The paradigm of teaching has shifted a lot over time (including the idea-oriented approach which is subsumed in system-oriented approaches). Looking across the development of the paradigms and trying to work out which categories developed requires a coding system over a review of textbooks in the field. If new competencies were added, then they were included in the category system and the coding started again. The resulting material could be referred to as “Possible candidates of Competencies in Informatics”, but those that are found in all of the previous approaches should be included as Competencies in Informatics. What about the key ones? Which of these are found in every part of informatics: theoretical, technical, practical and applied (under the German partitioning)? A key competency should be fundamental and ubiquitous.

The most important key competencies, by ranking, was algorithmic thinking, followed by design thinking, then analytic thinking (must look up the subtle difference here). (The paper contains all of the details) How can we gain competencies, especially these key ones, outside of a normative model that we have to apply to all contexts? We would like to be able to build on competencies, regardless of entry point, but taking into account prior learning so that we can build to a professional end point, regardless of starting point. What do we want to teach in the universities and to what degree?

The author finished on this point and it’s a good question: if we view our progression in terms of competency then how we can use these as building blocks to higher-level competencies? THis will help us in designing pre-requsitites and entry and exit points for all of our educational design.

The next talk was “Weaving Computing into all Middle School Disciplines”, presented by Susan Rodger from Duke. There were a lot of co-authors who were undergraduates (always good to see). The motivation for this project was there are problems with CS in the K-12 grades. It’s not taught in many schools and definitely missing in many high schools – not all Unis teach CS (?!?). Students don’t actually know what it is (the classic CS identify problem). There are also under-represented groups (women and minorities). Why should we teach it? 21st century skills, rewordings and many useful skills – from NCWIT.org.

Schools are already content-heavy so how do we convince people to add new courses? We can’t really so how about trying to weave it in to the existing project framework. Instead of doing a poster or a PowerPoint prevention, why not provide an animations that’s interactive in some way and that will involve computing. One way to achieve this is to use Alice, creating interactive stories or games, learning programming and computation concepts in a drag-and-drop code approach. Why Alice? There are many other good tools (Greenfoot, Lego, Scratch, etc) – well, it’s drag-and-drop, story-based and works well for women. The introductory Alice course in 2005 started to attract more women and now the class is more than 50% women. However, many people couldn’t come in because they didn’t have the prerequisites so the initiative moved out to 4th-6th grade to develop these skills earlier. Alice Virtual Worlds excited kids about computing, even at the younger ages.

The course “Adventures in Alice Programming” is aimed at grades 5-12 as Outreach, without having to use computing teachers (which would be a major restriction). There are 2-week teacher workshops where, initially, the teachers are taught Alice for a week, then the following week they develop lesson plans. There’s a one-week follow-up workshop the following summer. This initiative is funded until Summer, 2015, and has been run since 2008. There are sites: Durham, Charleston and Southern California. The teachers coming in are from a variety of disciplines.

How is this used on middle and high schools by teachers? Demonstrations, examples, interactive quizzes and make worlds for students to view. The students may be able to undertake projects, take and build quizzes, view and answer questions about a world, and the older the student, the more they can do.

Recruitment of teachers has been interesting. Starting from mailing lists and asking the teachers who come, the advertising has spread out across other conferences. It really helps to give them education credits and hours – but if we’re going to pay people to do this, how much do we need to pay? In the first workshop, paying $500 got a lot of teachers (some of whom were interested in Alice). The next workshop, they got gas money ($50/week) and this reduced the number down to the more interested teachers.

There are a lot of curriculum materials available for free (over 90 tutorials) with getting-started material as a one-hour tutorial showing basic set-up, placing objects, camera views and so on. There are also longer tutorials over several different stories. (Editor’s note: could we get away from the Princess/Dragon motif? The Princess says “Help!” and waits there to be rescued and then says “My Sweet Prince. I am saved.” Can we please arm the Princess or save the Knight?) There are also tutorial topics on inheritance, lists and parameter usage. The presenter demonstrated a lot of different things you can do with Alice, including book reports and tying Alice animations into the real world – such as boat trips which didn’t occur.

It was weird looking at the examples, and I’m not sure if it was just because of the gender of the authors, but the kitchen example in cooking with Spanish language instruction used female characters, the Princess/Dragon had a woman in a very passive role and the adventure game example had a male character standing in the boat. It was a small sample of the materials so I’m assuming that this was just a coincidence for the time being or it reflects the gender of the creator. Hmm. Another example and this time the Punnett Squares example has a grey-haired male scientist standing there. Oh dear.

Moving on, lots of helper objects are available for you to use if you’re a teacher to save on your development time which is really handy if you want to get things going quickly.

Finally, on discussing the impact, one 200 teachers have attend the workshops since 2008, who have then go on to teach 2900 students (over 2012-2013). From Google Analytics, over 20,000 users have accessed the materials. Also, a number of small outreach activities, Alice for an hour, have been run across a range of schools.

The final talk in this session was “Early validation of Computational Thinking Pattern Analysis”, presented by Hilarie Nickerson, from University of Colorado at Boulder. Computational thinking is important and, in the US, there have been both scope and pedagogy discussions, as well as instructional standards. We don’t have as much teacher education as we’d like. Assuming that we want the students to understand it, how can we help the teachers? Scalable Game Design integrates game and simulation design into public school curricula. The intention is to broaden participation for all kinds of schools as after-scjool classes had identified a lot of differences in the groups.

What’s the expectation of computational thinking? Administrators and industry want us to be able to take game knowledge and potentially use it for scientific simulation. A good game of a piece of ocean is also a predator-prey model, after all. Does it work? Well, it’s spread across a wide range of areas and communities, with more than 10,000 students (and a lot of different frogger games). Do they like it? There’s a perception that programming is cognitively hard and boring (on the congnitive/affective graph ranging from easy-hard/exciting-boring) We want it to be easy and exciting. We can make it easier with syntactic support and semantic support but making it exciting requires the students to feel ownership and to be able to express their creativity. And now they’re looking at the zone of proximal flow, which I’ve written about here. It’s good see this working in a project first, principles first model for these authors. (Here’s that picture again)

The results? The study spanned 10,000 students, 45% girls and 55% boys (pretty good numbers!), 48% underrepresented, with some middle schools exposing 350 students per year. The motivation starts by making things achievable but challenging – starting from 2D basics and moving up to more sophisticated 3D games. For those who wish to continue: 74% boys, 64% girls and 69% of minority students want to continue. There are other aspects that can raise motivation.

What about the issue of Computing Computational Thinking? The authors have created a Computational Thinking Pattern Analysis (CTPA) instrument that can track student learning trajectories and outcomes. Guided discovery, as a pedagogy, is very effective in raising motivation for both genders, where direct instruction is far less effective for girls (and is also less effective for boys).

How do we validate this? There are several computational thinking patterns grouped using latent semantic analysis. One of the simpler patterns for a game is the pair generation and absorption where we add things to the game world (trucks in Frogger or fish in predator/prey) and then remove them (truck gets off the screen/fish gets eaten). We also need collision detection. Measuring skill development across these skills will allow you to measure it in comparison to the tutorial and to other students. What does CTPA actually measure? The presence of code patterns that corresponded to computational thinking constructs suggest student skill with computational thinking (but doesn’t prove it) and is different from measuring learning. The graphs produced from this can be represented as a single number, which is used for validation. (See paper for the calculation!)

This has been running for two years now, with 39 student grades for 136 games, with the two human graders shown to have good inter-rater consistency. Frogger was not very heavily correlated (Spearman rank) but Sokoban, Centipede and the Sims weren’t bad, and removing design aspects of rubrics may improve this.

Was their predictive validity in the project? Did the CTPA correlate with the skill score of the final game produced? Yes, it appears to be significant although this is early work. CTPA does appear to be cabal of measuring CT patterns in code that correlate with human skill development. Future work on this includes the refinement of CTPA by dealing with the issue of non-orthogonal constructs (collisions that include generative and absorptive aspects), using more information about the rules and examining alternative calculations. The group are also working not oils for teachers, including REACT (real-time visualisations for progress assessment) and recommend possible skill trajectories based on their skill progression.

ITiCSE 2014, Day 2, Session4A, Software Engineering, #ITiCSE2014 #ITiCSE

Posted: June 24, 2014 Filed under: Education | Tags: collaboration, computer science education, education, educational problem, educational research, higher education, industry, ITiCSE, ITiCSE 2014, learning, mentoring, pair programming, pedagogy, principles of design, project based learning, small group learning, student perspective, studio based learning, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time, time factors, time management, universal principles of design, work-life balance Leave a comment- People: learning community

teachers and learners - Process: creative , reflective

- interactions

- physical space

- collaboration

- Product: designed object – a single focus for the process

- Intra-Group Relations: Group 1 has lots of strong characters and appeared to be competent and performing well, with students in group learning about Scrum from each other. Group 2 was more introverted, with no dominant or strong characters, but learned as a group together. Both groups ended up being successful despite the different paths. Collaborative learning inside the group occurred well, although differently.

- Inter-Group Relations: There was good collaborative learning across and between groups after the middle of the semester, where initially the groups were isolated (and one group was strongly focused on winning a prize for best project). Groups learned good practices from observing each other.

Education and Paying Back (#AdelEd #CSER #DigitalTechnologies #acara #SAEdu)

Posted: March 22, 2014 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: ACARA, advocacy, collaboration, community, cser, cser digital technologies, curriculum, design, digital education, digital technologies, education, educational problem, educational research, Generation Why, Google, higher education, learning, MOOC, Primary school, primary school teacher, principles of design, reflection, resources, school teachers, secondary school, sharing, teaching approaches, thinking, tools 2 CommentsOn Monday, the Computer Science Education Research Group and Google (oh, like you need a link) will release their open on-line course to support F-6 Primary school teachers in teaching the new Digital Technologies curriculum. We are still taking registrations so please go the course website if you want to sign up – or just have a look! (I’ve blogged about this recently as part of Science meets Parliament but you can catch it again here.) The course is open, on-line and free, released under Creative Commons so that the only thing people can’t do is to try and charge for it. We’re very excited and it’s so close to happening, I can taste it!

Here’s that link again – please, sign up!

I’m posting today for a few reasons. If you are a primary school teacher who wants help teaching digital technologies, we’d love to see you sign up and join our community of hundreds of other people who are thinking the same thing. If you know a primary school teacher, or are a principal for a primary school, and think that this would interest people – please pass it on! We are most definitely not trying to teach teachers how to teach (apart from anything else, what presumption!) but we’re hoping that what we provide will make it easier for teachers to feel comfortable, confident and happy with the new DT curriculum requirements which will lead to better experiences all ’round.

My other reason is one that came to me as I was recording my introduction section for the on-line course. In that brief “Oh, what a surprise there’s a camera” segment, I note that I consider the role of my teachers to have been essential in getting me to where I am today. This is what I’d like to do today: explicitly name and thank a few of my teachers and hope that some of what we release on Monday goes towards paying back into the general educational community.

My first thanks go to Mrs Shand from my Infant School in England. I was an early reader and, in an open plan classroom, she managed to keep me up with the other material while dealing with the fact that I was a voracious reader who would disappear to read at the drop of a hat. She helped to amplify my passion for reading, instead of trying to control it. Thank you!

In Australia, I ran into three people who were crucial to my development. Adam West was interested in everything so Grade 5 was full of computers (my first computing experience) because he arranged to borrow one and put it into the classroom in 1978, German (I can still speak the German I learnt in that class) and he also allowed us to write with nib and ink pens if we wanted – which was the sneakiest way to get someone’s handwriting and tidiness to improve that I have ever seen. Thank you, Adam! Mrs Lothian, the school librarian, also supported my reading habit and, after a while, all of the interesting books in the library often came through me very early on because I always returned them quickly and in good condition but this is where I was exposed to a whole world of interesting works: Nicholas Fisk, Ursula Le Guin and Susan Cooper not being the least of these. Thank you! Gloria Patullo (I hope I’ve spelt that correctly) was my Grade 7 teacher and she quickly worked out that I was a sneaky bugger on occasion and, without ever getting angry or raising a hand, managed to get me to realise that being clever didn’t mean that you could get away with everything and that being considerate and honest were the most important elements to alloy with smart. Thank you! (I was a pain for many years, dear reader, so this was a long process with much intervention.)

Moving to secondary school, I had a series of good teachers, all of whom tried to take the raw stuff of me and turn it into something that was happier, more useful and able to take that undirected energy in a more positive direction. I have to mention Ken Watson, Glenn Mulvihill, Mrs Batten, Dr Murray Thompson, Peter Thomas, Dr Riceman, Dr Bob Holloway, Milton Haseloff (I still have fossa, -ae, [f], ditch, burned into my brain) and, of course, Geoffrey Bean, headmaster, strong advocate of the thinking approaches of Edward de Bono and firm believer in the importance of the strength one needs to defend those who are less strong. Thank you all for what you have done, because it’s far too much to list here without killing the reader: the support, the encouragement, the guidance, the freedom to try things while still keeping a close eye, the exposure to thinking and, on occasion, the simple act of sitting me down to get me to think about what the heck I was doing and where I was going. The fact that I now work with some of them, in their continuing work in secondary education, is a wonderful thing and a reminder that I cannot have been that terrible. (Let’s just assume that, shall we? Moving on – rapidly…)

Of course, it’s not just the primary and secondary school teachers who helped me but they are the ones I want to concentrate on today, because I believe that the freedom and opportunities we offer at University are wonderful but I realise that they are not yet available to everyone and it is only by valuing, supporting and developing primary and secondary school education and the teachers who work so hard to provide it that we can go further in the University sector. We are lucky enough to be a juncture where dedicated work towards the national curriculum (and ACARA must be mentioned for all the hard work that they have done) has married up with an Industry partner who wants us all to “get” computing (Thank you, Google, and thank you so much, Sally and Alan) at a time when our research group was able to be involved. I’m a small part of a very big group of people who care about what happens in our schools and, if you have children of that age, you’ve picked a great time to send them to school. 🙂

I am delighted to have even a small opportunity to offer something back into a community which has given me so much. I hope that what we have done is useful and I can’t wait for it to start.

ASWEC 2014 – Now with Education Track

Posted: March 12, 2014 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, ASWEC, blogging, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, higher education, learning, measurement, principles of design, resources, software engineering, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentThe Australasian Software Engineering Conference has been around for 23 years and, while there have been previous efforts to add more focus on education, this year we’re very pleased to have a full day on Education on Wednesday, the 9th of April. (Full disclosure: I’m the Chair of the program committee for the Education track. This is self-advertising of a sort.) The speakers include a number of exciting software engineering education researchers and practitioners, including Dr Claudia Szabo, who recently won the SIGCSE Best Paper Award for a paper in software engineering and student projects.

Here’s the invitation from the conference chair, Professor Alan Fekete – please pass this on as far as you can!:

- Keynote by a leader of SE research, Prof Gail Murphy (UBC, Canada) on Getting to Flow in Software Development.

- Keynote by Alan Noble (Google) on Innovation at Google.

- Sessions on Testing, Software Ecosystems, Requirements, Architecture, Tools, etc, with speakers from around Australia and overseas, from universities and industry, that bring a wide range of perspectives on software development.

- An entire day (Wed April 9) focused on SE Education, including keynote by Jean-Michel Lemieux (Atlassian) on Teaching Gap: Where’s the Product Gene?