Why You Won’t Finish This Post

Posted: June 10, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, design, education, educational problem, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, universal principles of design 3 CommentsA friend of mine on Facebook posted a link to a Slate article entitled “You Won’t Finish This Article: Why people online don’t read to the end” and it’s told me everything that I’ve been doing wrong with this blog for about the last 410 hours. Now, this doesn’t even take into account that, by linking to something potentially more interesting on a well-known site, I’ve now buried the bottom of this blog post altogether because a number of you will follow the link and, despite me asking it to appear in a new window, you will never come back to this article. (This has quite obvious implications for the teaching materials we put up, so it’s well worth a look.)

Now, on the off-chance that you did come back (hi!), we have to assume that you didn’t read all of the linked article (if you read any at all) because 28% of you ‘bounced’ immediately and didn’t actually read much at all of that page – you certainly didn’t scroll. Almost none of you read to the bottom. What is, however, amusing is that a number of you will have either Liked or forwarded a link to one or both of these pages – never having stepped through or scrolled once, but because the concept at the start looks cool. Of course, according the Slate analysis, I’ve lost over half my readers by now. Of course, this does assume the Slate layout, where an image breaks things up and forces people to scroll through. So here’s an image that will discourage almost everyone from continuing. However, it is a pretty picture:

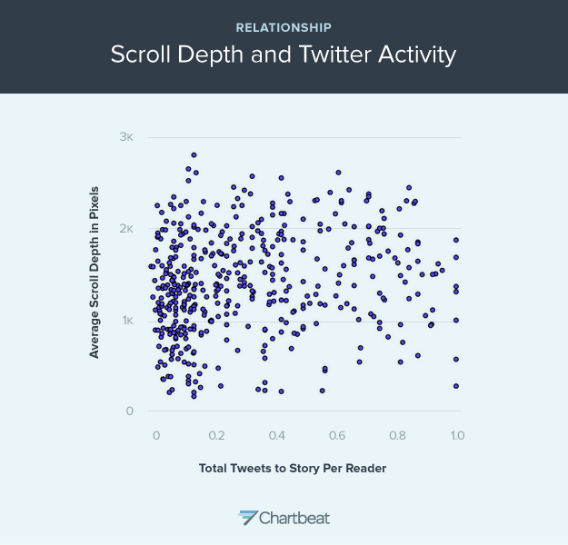

This graph shows the relationship between scroll depth and Tweet (From Slate and courtesy of Chartbeat)

What it says is that there is not an enormously strong correlation between depth of reading and frequency of tweet. So, the amount that a story is read doesn’t really tell you how much people will want to (or actually) share it. Overall, the Slate article makes it fairly clear that unless I manage to make my point in the first paragraph, I have little chance of being read any further – but if I make that first paragraph (or first images) appealing enough, any number of people will like and share it.

Of course, if people read down this far (thanks!) then they will know that I secretly start advocating the most horrible things known to humanity so, when someone finally follows their link and miraculously reads down this far, survives the Slate link out, and doesn’t end up mired in the picture swamp above, they will discover…

Oh, who am I kidding. I’ll just come back and fill this in later.

(Having stolen a time machine, I can now point out that this is yet another illustration of why we need to be thoughtful about what our students are going to do in response to on-line and hyperlinked materials rather than what we would like them to do. Any system that requires a better human, or a human to act in a way that goes against all the evidence we have of their behaviour, requires modification.)

SIGCSE 2013: Special Session on Designing and Supporting Collaborative Learning Activities

Posted: March 31, 2013 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, reflection, resources, sigcse, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design Leave a commentKatrina and I delivered a special session on collaborative learning activities, focused on undergraduates because that’s our area of expertise. You can read the outline document here. We worked together on the underlying classroom activities and have both implemented these techniques but, in this session, Katrina did most of the presenting and I presented the collaborative assessment task examples, with some facilitation.

The trick here is, of course, to find examples that are both effective as teaching tools and are effective as examples. The approach I chose to take was to remind everyone in the room of what the most important aspects were to making this work with students and I did this by deliberately starting with a bad example. This can be a difficult road to walk because, when presenting a bad example, you need to convince everyone that your choice was deliberate and that you actually didn’t just stuff things up.

My approach was fairly simple. Break people into groups, based on where they were currently sitting, and then I immediately went into the question, which had been tailored for the crowd and for my purposes:

“I want you to talk about the 10 things that you’re going to do in the next 5 years to make progress in your career and improve your job performance.”

And why not? Everyone in the room was interested in education and, most likely, had a job at a time when it’s highly competitive and hard to find or retain work – so everyone has probably thought about this. It’s a fair question for this crowd.

Well, it would be, if it wasn’t so anxiety inducing. Katrina and I both observed a sea of frozen faces as we asked a question that put a large number of participants on the spot. And the reason I did this was to remind everyone that anxiety impairs genuine participation and willingness to engage. There were a large number of frozen grins with darting eyes, some nervous mumbles and a whole lot of purposeless noise, with the few people who were actually primed to answer that question starting to lead off.

I then stopped the discussion immediately. “What was wrong with that?” I asked the group.

Well, where do we start? Firstly, it’s an individual activity, not a collaborative activity – there’s no incentive or requirement for discussion, groupwork or anything like that. Secondly, while we might expect people to be able to answer this, it is a highly charged and personal areas, and you may not feel comfortable discussing your five year plan with people that you don’t know. Thirdly, some people know that they should be able to answer this (or at least some supervisors will expect that they can) but they have no real answer and their anxiety will not only limit their participation but it will probably stop them from listening at all while they sweat their turn. Finally, there is no point to this activity – why are we doing this? What are we producing? What is the end point?

My approach to collaborative activity is pretty simple and you can read any amount of Perry, Dickinson, Hamer et al (and now us as well) to look at relevant areas and Contributing Student Pedagogy, where students have a reason to collaborate and we manage their developmental maturity and their roles in the activity to get them really engaged. Everyone can have difficulties with authority and recognising whether someone is making enough contribution to a discussion to be worth their time – this is not limited to students. People, therefore, have to believe that the group they are in is of some benefit to them.

So we stepped back. I asked everyone to introduce themselves, where they came from and give a fact about their current home that people might not know. Simple task, everyone can do it and the purpose was to tell your group something interesting about your home – clear purpose, as well. This activity launched immediately and was going so well that, when I tried to move it on because the sound levels were dropping (generally a good sign that we’re reaching a transition), some groups asked if they could keep going as they weren’t quite finished. (Monitoring groups spread over a large space can be tricky but, where the activity is working, people will happily let you know when they need more time.) I was able to completely stop the first activity and nobody wanted me to continue. The second one, where people felt that they could participate and wanted to say something, needed to keep going.

Having now put some faces to names, we then moved to a simple exercise of sharing an interesting teaching approach that you’d tried recently or seen at the conference and it’s important to note the different comfort levels we can accommodate with this – we are sharing knowledge but we give participants the opportunity to share something of themselves or something that interest them, without the burden of ownership. Everyone had already discovered that everyone in the group had some areas of knowledge, albeit small, that taught them something new. We had started to build a group where participants valued each other’s contribution.

I carried out some roaming facilitation where I said very little, unless it was needed. I sat down with some groups, said ‘hi’ and then just sat back while they talked. I occasionally gave some nodded or attentive feedback to people who looked like they wanted to speak and this often cued them into the discussion. Facilitation doesn’t have to be intrusive and I’m a much bigger fan of inclusiveness, where everyone gets a turn but we do it through non-verbal encouragement (where that’s possible, different techniques are required in a mixed-ability group) to stay out of the main corridor of communication and reduce confrontation. However, by setting up the requirement that everyone share and by providing a task that everyone could participate in, my need to prod was greatly reduced and the groups mostly ran themselves, with the roles shifting around as different people made different points.

We covered a lot of the underlying theory in the talk itself, to discuss why people have difficulty accepting other views, to clarify why role management is a critical part of giving people a reason to get involved and something to do in the conversation. The notion that a valid discursive role is that of the supporter, to reinforce ideas from the proposer, allows someone to develop their confidence and critically assess the idea, without the burden of having to provide a complex criticism straight away.

At the end, I asked for a show of hands. Who had met someone knew? Everyone. Who had found out something they didn’t know about other places? Everyone. Who had learned about a new teaching technique that they hadn’t known before. Everyone.

My one regret is that we didn’t do this sooner because the conversation was obviously continuing for some groups and our session was, sadly, on the last day. I don’t pretend to be the best at this but I can assure you that any capability I have in this kind of activity comes from understanding the theory, putting it into practice, trying it, trying it again, and reflecting on what did and didn’t work.

I sometimes come out of a lecture or a collaborative activity and I’m really not happy. It didn’t gel or I didn’t quite get the group going as I wanted it to – but this is where you have to be gentle on yourself because, if you’re planning to succeed and reflecting on the problems, then steady improvement is completely possible and you can get more comfortable with passing your room control over to the groups, while you move to the facilitation role. The more you do it, the more you realise that training your students in role fluidity also assists them in understanding when you have to be in control of the room. I regularly pass control back and forward and it took me a long time to really feel that I wasn’t losing my grip. It’s a practice thing.

It was a lot of fun to give the session and we spent some time crafting the ‘bad example’, but let me summarise what the good activities should really look like. They must be collaborative, inclusive, achievable and obviously beneficial. Like all good guidelines there are times and places where you would change this set of characteristics, but you have to know your group well to know what challenges they can tolerate. If your students are more mature, then you push out into open-ended tasks which are far harder to make progress in – but this would be completely inappropriate for first years. Even in later years, being able to make some progress is more likely to keep the group going than a brick wall that stops you at step 1. But, let’s face it, your students need to know that working in that group is not only not to their detriment, but it’s beneficial. And the more you do this, the better their groupwork and collaboration will get – and that’s a big overall positive for the graduates of the future.

To everyone who attended the session, thank you for the generosity and enthusiasm of your participation and I’m catching up on my business cards in the next weeks. If I promised you an e-mail, it will be coming shortly.

Doo de doo dooooo, doo de doo doo dooooo.

Posted: January 1, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, education, higher education, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, universal principles of design, vonnegut, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentSome of you will recognise the title of this post as the opening ‘music’ of the Europe song, “The Final Countdown”. I wasn’t sure what to call this post because it was the final component of a year long cycle that begin with some sketchy diagrams and a sketchier plan and has seen several different types of development over time. It is not, however, the final post on this blog as I intend to keep blogging but, from this post forwards, I will no longer require myself to provide at least one new post for every day.

This is, perhaps, just as well, because I am already looking over 2013 and realising that my ‘free project’ space is now completely occupied until July. Despite my intentions to travel less, I am in the US twice before the middle of March and have several domestic trips planned as well. And this is a reminder of everything that I’ve been trying to come to terms with in writing this blog and talking about my students, myself, and our community: I can talk about things and deal with them rationally in my head, but that doesn’t mean that I always act on them.

In retrospect, it has been a successful year and I have been able to produce more positive change in 2012 then probably in the sum of my working contributions up until that point. However, I am not in as good a shape as I was at the start of the year, for a variety of reasons, so when I say that my ‘free project’ space is full, I mean that I have fewer additional things to do but I am deliberately allocating less of my personal time to do them. In 2013, family and friends come first, then my projects, then my required work. Why? Because I will always find a way to do the work that I’m supposed to do, but if I start with that I can use all of my time to do that, whereas if I invert it, I have to be more efficient and I’m pretty confident that I can still get it done. After all, next year I’ll have at least an extra hour or two a day from not blogging.

Let’s not forget that this blogging project has consumed somewhere in the region of 350-400 hours of my time over the year, and that’s probably an underestimate. 400 hours is ten working weeks or just under 17 days of contiguous hours. Was my blog any better for being daily? Probably not. Could I be far more flexible and agile with my time if I removed the daily posting requirement? Of course – and so, away it goes. (So it goes, Mr Vonnegut.) The value to me of this activity has been immense – it has changed the way that I think about things and I have a far greater basis of knowledge from which I can discuss important aspects of learning and teaching. I have also discovered how little I know about some things but at least I know that they exist now! The value to other people is more debatable but given that I know that at least some people have found use in it, then it’s non-zero and I can live with that. Recalling Kurt Vonnegut again, and his book “Timequake”, I always saw this blog as a place where people could think “Oh, me too!” as I stumble my way through complicated ideas and try to comprehend the developed notions of clever people.

“Many people need desperately to receive this message: ‘I feel and think much as you do, care about many of the things you care about, although most people do not care about them. You are not alone.'” (Vonnegut, Timequake, 1997)

I never really thought much about the quality of this blog, but I was always concerned about the qualities of it. I wanted it to be inclusive, reliable, honest, humble, knowledgable, useful and welcoming. Looking back, I achieved some of that some of the time and, at other times, well, I’m a human. Some days I was angrier than others but I like to think it was about important things. Sexism makes me angry. Racism makes me angry. The corruption of science for political ends makes me angry. Deliberate ignorance makes me angry. Inequity and elitism make me angry. I hope, however, the anger was a fuel for something better, burning to lift something up that carried a message that wasn’t just pure anger. If, at any stage, all I did was combine oxygen and kerosene on the launch pad and burn the rocket, then I apologise, because I always wanted to be more useful than that.

This is not the end of the blog, but it’s the end of one cycle. It’s like a long day at the beach. You leap out of bed as the sun is coming up, grab some fruit and run down to the water, still warm from the late summer currents and the hot wind that blows across it, diving in to swim out and look back at the sand as it lights up. Maybe you grab your fishing rod and spend an hour or two watching the float bob along the surface, more concerned with talking to your friend or drinking a beer than actually catching a fish, because it’s just such a nice day to be with people. Lunch is sandy sandwiches, eaten between laughs in the gusty breeze that lifts up the beach and tries to jam a big handful of grains into every bite, so you juggle it and the tomato slides out, landing on your lap. That’s ok, because all you have to do is to dive back into the water and you’re clean again. The afternoon is beach cricket, squinting even through sunglasses as some enthusiastic adult hits the ball for a massive 6 that requires everyone to search for it for about 15 minutes, then it’s some cold water and ice creams. Heading back that night, and it’s a long day in an Australian summer, you’re exhausted, you’re spent. You couldn’t swim another stroke, eat another chip or run for another ball if you tried. You’ll eat something for dinner and everyone will mumble about staying up but the day is over and, in an hour or so, everyone will be asleep. You might try and stay up because there’s so much to do but the new day starts tomorrow. Or, worst case, next summer. It’s not the end of the beach. It’s just the end of one day.

Firstly, of course, I want to thank my wife who has helped me to find the time I needed to actually do this and who has provided a very patient ear when I am moaning about that most first world of problems: what is my blog theme for today. The blog has been a part of our lives every day for 1-2 hours for an entire year and that requires everyone in the household to put in the effort – so, my most sincere gratitude to the amazing Dr K. There’s way I could have done any of this without you.

For everyone who is not my wife, thank you for reading and being part of what has been a fascinating journey. Thank you for all of your comments, your patience, your kindness and your willingness to listen. I hope that you have a very happy and prosperous New Year. Remember what Vonnegut said; that people need to know, sometimes, that they are not alone.

I’ll see you tomorrow.

Thanks for the exam – now I can’t help you.

Posted: December 31, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, tools, universal principles of design, vygotsky, workload 1 CommentI have just finished marking a pile of examinations from a course that I co-taught recently. I haven’t finalised the marks but, overall, I’m not unhappy with the majority of the results. Interestingly, and not overly surprisingly, one of the best answered sections of the exam was based on a challenging essay question I set as an assignment. The question spans many aspects of the course and requires the student to think about their answer and link the knowledge – which most did very well. As I said, not a surprise but a good reinforcement that you don’t have to drill students in what to say in the exam, but covering the requisite knowledge and practising the right skills is often helpful.

However, I don’t much like marking exams and it doesn’t come down to the time involved, the generally dull nature of the task or the repetitive strain injury from wielding a red pen in anger, it comes down to the fact that, most of the time, I am marking the student’s work at a time when I can no longer help him or her. Like most exams at my Uni, this was the terminal examination for the course, worth a substantial amount of the final marks, and was taken some weeks after teaching finished. So what this means is that any areas I identify for a given student cannot now be corrected, unless the student chooses to read my notes in the exam paper or come to see me. (Given that this campus is international, that’s trickier but not impossible thanks to the Wonders of Skypenology.) It took me a long time to work out exactly why I didn’t like marking, but when I did, the answer was obvious.

I was frustrated that I couldn’t actually do my job at one of the most important points: when lack of comprehension is clearly identified. If I ask someone a question in the classroom, on-line or wherever, and they give me an answer that’s not quite right, or right off base, then we can talk about it and I can correct the misunderstanding. My job, after all, is not actually passing or failing students – it’s about knowledge, the conveyance, construction and quality management thereof. My frustration during exam marking increases with every incomplete or incorrect answer I read, which illustrates that there is a section of the course that someone didn’t get. I get up in the morning with the clear intention of being helpful towards students and, when it really matters, all I can do is mark up bits of paper in red ink.

Quickly, Jones! Construct a valid knowledge framework! You’re in a group environment! Vygotsky, man, Vygotsky!

A student who, despite my sweeping, and seeping, liquid red ink of doom, manages to get a 50 Passing grade will not do the course again – yet this mark pretty clearly indicates that roughly half of the comprehension or participation required was not carried out to the required standard. Miraculously, it doesn’t matter which half of the course the student ‘gets’, they are still deemed to have attained the knowledge. (An interesting point to ponder, especially when you consider that my colleagues in Medicine define a Pass at a much higher level and in far more complicated ways than a numerical 50%, to my eternal peace of mind when I visit a doctor!) Yet their exam will still probably have caused me at least some gnashing of teeth because of points missed, pointless misstatement of the question text, obscure song lyrics, apologies for lack of preparation and the occasional actual fact that has peregrinated from the place where it could have attained marks to a place where it will be left out in the desert to die, bereft of the life-giving context that would save it from such an awful fate.

Should we move the exams earlier and then use this to guide the focus areas for assessment in order to determine the most improvement and develop knowledge in the areas in most need? Should we abandon exams entirely and move to a continuous-assessment competency based system, where there are skills and knowledge that must be demonstrated correctly and are practised until this is achieved? We are suffering, as so many people have observed before, from overloading the requirement to grade and classify our students into neatly discretised performance boxes onto a system that ultimately seeks to identify whether these students have achieved the knowledge levels necessary to be deemed to have achieved the course objectives. Should we separate competency and performance completely? I have sketchy ideas as to how this might work but none that survive under the blow-torches of GPA requirements and resource constraints.

Obviously, continuous assessment (practicals, reports, quizzes and so on) throughout the semester provide a very valuable way to identify problems but this requires good, and thorough, course design and an awareness that this is your intent. Are we premature in treating the exam as a closing-off line on the course? Do we work on that the same way that we do any assignment? You get feedback, a mark and then more work to follow-up? If we threw resourcing to the wind, could we have a 1-2 week intensive pre-semester program that specifically addressed those issues that students failed to grasp on their first pass? Congratulations, you got 80%, but that means that there’s 20% of the course that we need to clarify? (Those who got 100% I’ll pay to come back and tutor, because I like to keep cohorts together and I doubt I’ll need to do that very often.)

There are no easy answers here and shooting down these situations is very much in the fish/barrel plane, I realise, but it is a very deeply felt form of frustration that I am seeing the most work that any student is likely to put in but I cannot now fix the problems that I see. All I can do is mark it in red ink with an annotation that the vast majority will never see (unless they receive the grade of 44, 49, 64, 74 or 84, which are all threshold-1 markers for us).

Ah well, I hope to have more time in 2013 so maybe I can mull on this some more and come up with something that is better but still workable.

Thinking about teaching spaces: if you’re a lecturer, shouldn’t you be lecturing?

Posted: December 30, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design, vygotsky Leave a commentI was reading a comment on a philosophical post the other day and someone wrote this rather snarky line:

He’s is a philosopher in the same way that (celebrity historian) is a historian – he’s somehow got the job description and uses it to repeat the prejudices of his paymasters, flattering them into thinking that what they believe isn’t, somehow, ludicrous. (Grangousier, Metafilter article 123174)

Rather harsh words in many respects and it’s my alteration of the (celebrity historian)’s name, not his, as I feel that his comments are mildy unfair. However, the point is interesting, as a reflection upon the importance of job title in our society, especially when it comes to the weighted authority of your words. From January the 1st, I will be a senior lecturer at an Australian University and that is perceived differently where I am. If I am in the US, I reinterpret this title into their system, namely as a tenured Associate Professor, because that’s the equivalent of what I am – the term ‘lecturer’ doesn’t clearly translate without causing problems, not even dealing with the fact that more lecturers in Australia have PhDs, where many lecturers in the US do not. But this post isn’t about how people necessarily see our job descriptions, it’s very much about how we use them.

In many respects, the title ‘lecturer’ is rather confusing because it appears, like builder, nurse or pilot, to contain the verb of one’s practice. One of the big changes in education has been the steady acceptance of constructivism, where the learners have an active role in the construction of knowledge and we are facilitating learning, in many ways, to a greater extent than we are teaching. This does not mean that teachers shouldn’t teach, because this is far more generic than the binding of lecturers to lecturing, but it does challenge the mental image that pops up when we think about teaching.

If I asked you to visualise a classroom situation, what would you think of? What facilities are there? Where are the students? Where is the teacher? What resources are around the room, on the desks, on the walls? How big is it?

Take a minute to do just this and make some brief notes as to what was in there. Then come back here.

It’s okay, I’ll still be here!

Adelaide Computing Education Conventicle 2012: “It’s all about the people”

Posted: December 27, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: acec2012, advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, conventicle, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, reconciliation, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, universal principles of design 1 Commentacec 2012 was designed to be a cross-University event (that’s the whole point of the conventicles, they bring together people from a region) and we had a paper from the University of South Australia: ‘”It’s all about the people”; building cultural competence in IT graduates’ by Andrew Duff, Kathy Darzanos and Mark Osborne. Andrew and Kathy came along to present and the paper was very well received, because it dealt with an important need and a solid solution to address that need, which was inclusive, insightful and respectful.

For those who are not Australians, it is very important to remember that the original inhabitants of Australia have not fared very well since white settlement and that the apology for what happened under many white governments, up until very recently, was only given in the past decade. There is still a distance between the communities and the overall process of bringing our communities together is referred to as reconciliation. Our University has a reconciliation statement and certain goals in terms of representation in our staff and student bodies that reflect percentages in the community, to reduce the underrepresentation of indigenous Australians and to offer them the same opportunities. There are many challenges facing Australia, and the health and social issues in our indigenous communities are often exacerbated by years of poverty and a range of other issues, but some of the communities have a highly vested interest in some large-scale technical, ICT and engineering solutions, areas where indigenous Australians are generally not students. Professor Lester Irabinna Rigney, the Dean of Aboriginal Education, identified the problem succinctly at a recent meeting: when your people live on land that is 0.7m above sea level, a 0.9m sea-level rise starts to become of concern and he would really like students from his community to be involved in building the sea walls that address this, while we look for other solutions!

Andrea, Kathy and Mark’s aim was to share out the commitment to reconciliation across the student body, making this a whole of community participation rather than a heavy burden for a few, under the guiding statement that they wanted to be doing things with the indigenous community, rather than doing things to them. There’s always a risk of premature claiming of expertise, where instead of working with a group to find out what they want, you walk in and tell them what they need. For a whole range of very good and often heartbreaking reasons, the Australian indigenous communities are exceedingly wary when people start ordering them about. This was the first thing I liked about this approach: let’s not make the same mistakes again. The authors were looking for a way to embed cultural awareness and the process of reconciliation into the curriculum as part of an IT program, sharing it so that other people could do it and making it practical.

Their key tenets were:

- It’s all about the diverse people. They developed a program to introduce students to culture, to give them more than one world view of the dominant culture and to introduce knowledge of the original Australians. It’s an important note that many Australians have no idea how to use certain terms or cultural items from indigenous culture, which of course hampers communication and interaction.

For the students, they were required to put together an IT proposal, working with the indigenous community, that they would implement in the later years of their degree. Thus, it became part of the backbone of their entire program.

- Doing with [people], not to [people]. As discussed, there are many good reasons for this. Reduce the urge to be the expert and, instead, look at existing statements of right and how to work with other peplum, such as the UN rights of indigenous people and the UniSA graduate attributes. This all comes together in the ICUP – Indigenous Content in Undergraduate Program

How do we deal with information management in another culture? I’ve discussed before the (to many) quite alien idea that knowledge can reside with one person and, until that person chooses or needs to hand on that knowledge, that is the person that you need. Now, instead of demanding knowledge and conformity to some documentary standard, you have to work with people. Talking rather than imposing, getting the client’s genuine understanding of the project and their need – how does the client feel about this?

Not only were students working with indigenous people in developing their IT projects, they were learning how to work with other peoples, not just other people, and were required to come up with technologically appropriate solutions that met the client need. Not everyone has infinite power and 4G LTE to run their systems, nor can everyone stump up the cash to buy an iPhone or download apps. Much as programming in embedded systems shakes students out of the ‘infinite memory, disk and power’ illusion, working with other communities in Australia shakes them out of the single worldview and from the, often disrespectful, way that we deal with each other. The core here is thinking about different communities and the fact that different people have different requirements. Sometimes you have to wait to speak to the right person, rather than the available person.

The online forum has four questions that students have to find a solution to, where the forum is overseen by an indigenous tutor. The four questions are:

- What does culture mean to you?

- Post a cultural artefact that describes your culture?

- I came here to study Computer Science – not Aboriginal Australians?

- What are some of the differences between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians?

The first two are amazing questions – what is your answer to question number 2? The second pair of questions are more challenging and illustrate the bold and head-on approach of this participative approach to reconciliation. Reconciliation between all of the Australian communities requires everyone to be involved and, being honest, questions 3 and 4 are going to open up some wounds, drag some silly thinking out into the open but, most importantly, allow us to talk through issues of concern and confusion.

I suspect that many people can’t really answer question 4 without referring back to mid-50s archetypal depictions of Australian Aborigines standing on one leg, looking out over cliffs, and there’s an excellent ACMI (Australian Centre for the Moving Image) exhibit in Melbourne that discusses this cultural misappropriation and stereotyping. One of the things that resonated with me is that asking these questions forces people to think about these things, rather than repeating old mind grooves and received nonsense overheard in pubs, seen on TV and heard in racist jokes.

I was delighted that this paper was able to be presented, not least because the goal of the team is to share this approach in the hope of achieving even greater strides in the reconciliation process. I hope to be able to bring some of it to my Uni over the next couple of years.

Education is not Music: A Long Winded Agreement with Aaron Bady

Posted: December 18, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, community, curriculum, design, education, educational research, ethics, Generation Why, higher education, moocs, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, universal principles of design Leave a commentMark Guzdial has been posting a great deal on MOOCs, as have we all although Mark is much easier to read than I am, and his recent comment on Aaron Bady’s response to Clay Shirky’s “Udacity is Napster” drew me to the great article by Bady and the following key quote inside Bady’s article:

“I think teaching is very different from music”

and I couldn’t agree more. Let me briefly list why I feel that a comparison to Napster has no real validity, to agree with Aaron that Clay Shirky’s argument is not well grounded for the discussion of education. What’s interesting is that I believe that Shirky identifies this point in his own essay, but doesn’t quite realise the full implications of what he’s saying:

Starting with Edison’s wax cylinders, and continuing through to Pandora and the iPod, the biggest change in musical consumption has come not from production but playback.

…

Those earlier inventions systems started out markedly inferior to the high-cost alternative: records were scratchy, PCs were crashy. But first they got better, then they got better than that, and finally, they got so good, for so cheap, that they changed people’s sense of what was possible.

The first thing we need to remember about music is that music is inherently fungible because, when viewed as a piece of work, you can replace it with another effectively identical item. Of course, here we need to be careful and define what we need by identical, because music, as it turns out, is almost never identical but it gets treated that way. If you doubt this, then go and review how much it costs to insert the song “Happy Birthday to You” into a movie or TV show. It doesn’t matter if it’s Homer Simpson yelling it drunkenly, or the Three Tenors singing it sotto voce as part of an Ally McBeal shower hallucination flashback, you will still be liable to fork out dollars to the company who claims to hold the copyright. If you understand the history of how we even made music small enough to send across the (much, much slower back then) Internet, we had to start with the MP3 format, which threw away enough ‘unneeded’ data from the original CD files to shrink the files to a little less than 10% of their original size. This is the technology that we needed before we could even get around the idea of Napster, because enough people had enough music on their hard drives (because we’d already dropped the size) to make file sharing useful. However, as Shirky also notes in his article, this lossy compression technique changes the way that music sounds and you can tell the difference if you listen carefully and know what to listen for. Yet, this is the same song and Napster got into trouble for sharing compressed artefacts of lower quality and perceptible difference from the CD originals, because music, as this kind of artefact, is fungible despite very different levels of quality. Identical, to an audiophile, means sounding precisely the same (or true to the source, really), but identical to the copyright owner is a representation that clearly indicates unauthorised use of copyright material – which is why George Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord” ended up begin described as sufficiently similar to “He’s So Fine”, despite it being a brand new recording and not just a compressed copy.

So, yes, Shirky’s original quotes are both true – we have improved playback and while MP3 is still very common, lossless and much higher quality reproductions are now available. However, the point that has been missed is that the vast majority of people do not care in the slightest. The average person will only notice a shift from MP3 to lossless if they suddenly discover that their iPod has dropped in capacity, when measured in number of songs, by a significant margin. If I listen to “Viva La Vida” by Coldplay, and yes, Joe Satriani fans, I picked that deliberately, then the effective difference in my enjoyment of the song, my ability to sing along tunelessly in the shower and the ability to recite the words if asked, has nothing to do with the quality. This is not true of certain pieces of classical music, where the compression artefacts start to have more of an effect, but these are not the core business of file sharers and those who trade in compressed artefacts. However, MP3 artefacts rarely sound like long scratches, dust on the record or a bad needle – yes, they can be irritating, but the electronic form, pre and post-compression, is generally protected from such things unless you get some serious cosmic ray action in your storage media and even then, you have to be very unlucky.

The Napster music argument, for me, falls down because the increase in quality does not have a direct connection to what the majority of the user base would have considered an acceptable product. Yes, it’s better now but, for most people, so what? Music sharing services are considered useful and valuable because they share songs that people want, where most people don’t think about the quality, they accept the name and the recognisable nature of the song as enough.

This is not at all true for education, because educational experiences vary wildly between lecturers, courses, institutions and eras to an extent that it is impossible to consider them in any way to be interchangeable – quality, here, is everything. If you have an international articulation program, you know that the first thing you have to do is to work out what has been taught, and how it has been taught, inside a course of the same name as one of yours. Even ‘name equivalence’ doesn’t mean anything here and we do not, or we should not, grant standing based on a coincidence of name for a course. There is no parallel guarantee that my low quality version of a course will give me the same ability to “sing in the shower” as the high quality course will – and this is, for me, an unassailable difference.

There is no doubt that the opportunities that might be offered by blended learning, full electronic offerings, and, yes, MOOCs (however they end up being defined) are something that we have to consider because, if they work, they allow us to educate the world, but claiming that this must occur because Udacity is like Napster completely ignores the core difference between education and music in terms of the consumer base and their focus on what it means for a service to meet their requirements. If students didn’t care about the perceived quality, then we wouldn’t have the notion of the ‘top schools’ or ‘low end schools’, so we know that this thinking exists. A student will happily put an MP3 on at a party, but it remains to be seen if they will constantly and out of design, not desperation, put a MOOC course on a job application, and expect a good result from it.

Taught for a Result or Developing a Passion

Posted: December 13, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, Bloom, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, learning, measurement, MIKE, PIRLS, PISA, principles of design, reflection, research, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design, workload Leave a commentAccording to a story in the Australian national broadcaster, the ABC, website, Australian school children are now ranked 27th out of 48 countries in reading, according to the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study, and that a quarter of Australia’s year 4 students had failed to meet the minimum standard defined for reading at their age. As expected, the Australian government has said “something must be done” and the Australian Federal Opposition has said “you did the wrong thing”. Ho hum. Reading the document itself is fascinating because our fourth graders apparently struggle once we move into the area of interpretation and integration of ideas and information, but do quite well on simple inference. There is a lot of scope for thought about how we are teaching, given that we appear to have a reasonably Bloom-like breakdown on the data but I’ll leave that to the (other) professionals. Another international test, the Program for International School Assessment (PISA) which is applied to 15 year olds, is something that we rank relatively highly in, which measures reading, mathematics and science. (And, for the record, we’re top 10 on the PISA rankings after a Year 4 ranking of 27th. Either someone has gone dramatically wrong in the last 7 years of Australian Education, or Year 4 results on PIRLS doesn’t have as much influence as we might have expected on the PISA).We don’t yet have the results for this but we expect it out soon.

What is of greatest interest to me from the linked article on the ABC is the Oslo University professor, Svein Sjoberg, who points out the comparing educational systems around the globe is potentially too difficult to be meaningful – which is a refreshingly honest assessment in these performance-ridden and leaderboard-focused days. As he says:

“I think that is a trap. The PISA test does not address the curricular test or the syllabus that is set in each country.

Like all of these tests, PIRLS and PISA measure a student’s ability to perform on a particular test and, regrettably, we’re all pretty much aware, or should be by now, that using a test like this will give you the results that you built the test to give you. But one thing that really struck me from his analysis of the PISA was that the countries who perform better on the PISA Science ranking generally had a lower measure of interest in science. Professor Sjoberg noted that this might be because the students had been encouraged to become result-focused rather than encouraging them to develop a passion.

If Professor Sjoberg is right, then is not just a tragedy, it’s an educational catastrophe – we have now started optimising our students to do well in tests but be less likely to go and pursue the subjects in which they can get these ‘good’ marks. If this nasty little correlation holds, then will have an educational system that dominates in the performance of science in the classroom, but turns out fewer actual scientists – our assessment is no longer aligned to our desired outcomes. Of course, what it is important to remember is that the vast majority of these rankings are relative rather than absolute. We are not saying that one group is competent or incompetent, we are saying that one group can perform better or worse on a given test.

Like anything, to excel at a particular task, you need to focus on it, practise it, and (most likely) prioritise it above something else. What Professor Sjoberg’s analysis might indicate, and I realise that I am making some pretty wild conjecture on shaky evidence, is that certain schools have focused the effort on test taking, rather than actual science. (I know, I know, shock, horror) Science is not always going to fit into neat multiple choice questions or simple automatically marked answers to questions. Science is one of the areas where the viva comes into its own because we wish to explore someone’s answer to determine exactly how much they understand. The questions in PISA theoretically fall into roughly the same categories (MCQ, short answer) as the PIRLS so we would expect to see similar problems in dealing with these questions, if students were actually having a fundamental problem with the questions. But, despite this, the questions in PISA are never going to be capable of gauging the depth of scientific knowledge, the passion for science or the degree to which a student already thinks within the discipline. A bigger problem is the one which always dogs standardised testing of any sort, and that is the risk that answering the question correctly and getting the question right may actually be two different things.

Years ago, I looked at the examination for a large company’s offering in a certain area, I have no wish to get sued so I’m being deliberately vague, and it became rapidly apparent that on occasion there was a company answer that was not the same as the technically correct answer. The best way to prepare for the test was not to study the established base of the discipline but it was to read the corporate tracts and practise the skills on the approved training platforms, which often involved a non-trivial fee for training attendance. This was something that was tangential to my role and I was neither of a sufficiently impressionable age nor strongly bothered enough by it for it to affect me. Time was a factor and incorrect answers cost you marks – so I sat down and learned the ‘right way’ so that I could achieve the correct results in the right time and then go on to do the work using the actual knowledge in my head.

However, let us imagine someone who is 14 or 15 and, on doing the practice tests for ‘test X’ discovers that what is important is in hitting precisely the right answer in the shortest time – thinking about the problem in depth is not really on the table for a two-hour exam, unless it’s highly constrained and students are very well prepared. How does this hypothetical student retain respect for teachers who talk about what science is, the purity of mathematics, or the importance of scholarship, when the correct optimising behaviour is to rote-learn the right answers, or the safe and acceptable answers, and reproduce those on demand. (Looking at some of the tables in the PISA document, we see that the best performing nations in the top band of mathematical thinking are those with amazing educational systems – the desired range – and those who reputedly place great value in high power-distance classrooms with large volumes of memorisation and received wisdom – which is probably not the desired range.)

Professor Sjoberg makes an excellent point, which is that trying to work out what is in need of fixing, and what is good, about the Australian education system is not going to be solved by looking at single figure representations of our international rankings, especially when the rankings contradict each other on occasion! Not all countries are the same, pedagogically, in terms of their educational processes or their power distances, and adjacency of rank is no guarantee that the two educational systems are the same (Finland, next to Shanghai-China for instance). What is needed is reflection upon what we think constitutes a good education and then we provide meaningful local measures that allow us to work out how we are doing with our educational system. If we get the educational system right then, if we keep a bleary eye on the tests we use, we should then test well. Optimising for the tests takes the effort off the education and puts it all onto the implementation of the test – if that is the case, then no wonder people are less interested in a career of learning the right phrase for a short answer or the correct multiple-choice answer.

“You Will Never Amount to Anything!”

Posted: December 10, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, curriculum, education, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, led zeppelin, measurement, principal skinner, principles of design, reflection, resources, simpsons, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentI am currently reading “When Giants Walked the Earth: A Biography of Led Zeppelin” by Mick Wall. I won’t go into much of the detail of the book but the message presented around the four members of the group is that most of them did not have the best experiences in school and that, in at least two cases, the statements written on their reports by their teachers were profoundly dismissive. Now, it is of course entirely possible the that the Led Zep lads were, at time of leaving school, incapable of achieving anything – except that this is a total nonsense as it is quite obvious that they achieved a degree of musical and professional success that few contemplate, let alone reach.

You’ll often read this kind of line in celebrity biographies – that semi-mythical reforging of the self after having been judged and found wanting. (From a narrative perspective, it’s not all that surprising as it’s an easy way to increase the tension.) But one of the reasons that it pops up is that such a statement is so damning that it is not surprising that a successful person might want to wander back to the person who said it and say “Really?” But to claim that such a statement is a challenge (as famously mocked in the Simpsons where Principal Skinner says that these children have not future and is forced to mutter, with false bonhomie, ‘Prove me wrong, kids, prove me wrong.’) is confused at best, disingenuous and misdirecting at worst. If you want someone to achieve something, provide a clear description of the task, the means to achieve that task and then set about educating and training. No-one has ever learned brain surgery by someone yelling “Don’t open that skull” so pretending that an entire life’s worth of motivation can be achieved by telling something that they have no worth is piffle. Possibly even balderdash.

The phrase “You Will Never Amount To Anything” is, in whatever form it is uttered, a truly useless sentiment. It barely has any meaning (isn’t just being alive being something and hence amounting to a small sort of anything?) but, of course, it is not stated in order to achieve an outcome other than to place the blame for the lack of engagement with a given system squarely at the feet of the accused. You have failed to take advantage of the educational opportunities that we have provided and this is such a terminal fault, that the remaining 90% of your life will be spent in a mobile block of amber, where you will be unable to affect any worthwhile interaction with the universe.

I note that, with some near misses, I have been spared this kind of statement but I do feel very strongly that it is really not anything that you can with any credibility or useful purpose. If you happen to be Death, the Grim Reaper, then you can stand at the end of someone’s life and say “Gosh, you didn’t do a great deal did you” (although, again, what does it mean to do anything anyway?) but saying it when someone is between the ages of 16 and 20? You might be able to depend upon the statistical reliability that, if rampant success in our society is only given to 1%, 99% of the time, everyone you say “You will not be a success” will accidentally fall into that category. It’s quite obvious that any number of the characteristics that are worthy of praise in school contribute nothing to the spectacular success enjoyed by some people, where these characteristics are “sitting quietly”, “wearing the correct uniform” or “not chewing gum”. These are excellent facets of compliance and will make for citizens who may be of great utility to the successful, but it’s hard to see many business leaders whose first piece of advice to desperate imitators is “always wear shiny shoes”.

If we are talking about perceived academic ability then we run into another problem, in that there is a great deal of difference between school and University, let along school and work. There is no doubt that the preparation offered by a good schooling system is invaluable. Reading, writing, general knowledge, science, mathematics, biology, the classics… all of these parts of our knowledge and our society can be introduced to students very usefully. But to say that your ability to focus on long division problems when you are 14 is actually going to be the grand limiting factor on your future contribution to the world? Nonsense.

Were you to look at my original degree, you might think “How on Earth did this man end up with a PhD? He appears to have no real grasp of study, or pathway through his learning.” and, at the time of the degree, you’d be right. But I thought about what had happened, learned from it, and decided to go back and study again in order to improve my level of knowledge and my academic record. I then went back and did this again. And again. Because I persevered, because I received good advice on how to improve and, most importantly, because a lot of people took the time to help me, I learned a great deal and I became a better student. I developed my knowledge. I learned how to learn and, because of that, I started to learn how to think about teaching, as well.

If you were to look at Nick Falkner at 14, you may have seen some potential but a worry lack of diligence and effort. At 16, you would have seen him blow an entire year of school exams because he didn’t pay attention. At 17 he made it into Uni, just, but it wasn’t until the wheels really started to fall off that he realised that being loquacious and friendly wasn’t enough. Scurrying out of Uni with a third-grade degree into a workforce that looked at the evidence of my learning drove home that improvements were to be made. Being unemployed for most of a year cemented it – I had set myself up for a difficult life and had squandered a lot of opportunities. And that is when serendipity intervened, because the man who has the office next to me now, and with whom I coffee almost every morning, suggested that I could come back and pursue a Masters degree to make up for the poor original degree, and that I would not have to pay for it upfront because it was available as a government deferred-payment option. (Thank you, again, Kevin!)

That simple piece of advice changed my life completely. Instead of not saying anything or being dismissive of a poor student, someone actually took the time to say “Well, here’s something you could do and here’s how you do it.” And now, nearly 20 years down the track, I have a PhD, a solid career in which I am respected as an educator and as a researcher and I get to inspire and help other students. There’s no guarantee that good advice will always lead to good outcomes (and we all know about the paving on the road to Hell) but it’s increasingly obvious to me that dismissive statements, unpleasant utterances and “cut you loose” curtness are far more likely to do nothing positive at all.

If the most that you can say to a student is “You’re never going to amount to anything”, it might be worth looking in a mirror to see exactly what you’ve amounted to yourself…