Time to Work and Time to Play

Posted: May 19, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, work/life balance, workload 1 CommentI do a lot of grounded theory research into student behaviour patterns. It’s a bit Indiana Jones in a rather dry way: hear a rumour of a giant cache of data, hack your way through impenetrable obfuscation and poor data alignment to find the jewel at the centre, hack your way out and try to get it to the community before you get killed by snakes, thrown into a propellor or eaten. (Perhaps the analogy isn’t perfect but how recently have you been through a research quality exercise?) Our students are all pretty similar, from the metrics I have, and I’ve gone on at length about this in other posts: hyperbolic time-discounting and so on. Embarrassingly recently, however, I was introduced to the notion of instrumentality, the capability to see that achieving a task now will reduce the difficulty in completing a goal later. If we can’t see how important this is to getting students to do something, maybe it’s time to have a good sit-down and a think! Husman et al identify three associated but distinguishable aspects to a student’s appreciation of a task: how much they rate its value, their intrinsic level of motivation, and their appreciation of the instrumentality. From this study, we have a basis for the confusing and often paradoxical presentation of a student who is intelligent and highly motivated – but just not for the task we’ve given them, despite apparently and genuinely being aware of the value of the task. Without the ability to link this task to future goal success, the exponential approach of the deadline horizon can cause a student to artificially inflate the value of something of less final worth, because the actual important goal is out of sight. But rob a student of motivation and we have to put everything into a high-stakes, heavily temporally fixed into the almost immediate future and the present, often resorting to extrinsic motivating factors (bribes/threats) to impose value. This may be why everyone who uses a punishment/reward situation achieves compliance but then has to keep using this mechanism to continue to keep values artificially high. Have we stumbled across an Economy of Pedagogy? I hope not, because I can barely understand basic economics. But we can start to illustrate why the student has to be intrinsically connected to the task and the goal framework – without it, it’s carrot/stick time and, once we do that, it’s always carrot/stick time.

Like almost every teacher I know, all of my students are experts at something but mining that can be tricky. What quickly becomes apparent, and as McGonigall reflected on in “Reality is Broken”, is that people will put far more effort into an activity that they see as play than one which they see as work. I, for example, have taken up linocut printing and, for no good reason at all, have invested days into a painstaking activity where it can take four hours to achieve even a simple outcome of reasonable quality – and it will be years before I’m good at it. Yet the time I spend at the printing studio on Saturdays is joyful, recharging and, above all, playful. If I consumed 6 hours marking assignments, writing a single number out of 10 and restricting my comments to good/bad/try harder, then I would feel spent and I would dread starting, putting it off as long as possible. Making prints, I consumed about 6 hours of effort to scan, photoshop, trim, print, reverse, apply over carbon paper, trace, cut out of lino and then manually and press print about four pieces of paper – and I felt like a new man. No real surprises here. In both cases, I am highly motivated. One task has great value to my students and me because it provides useful feedback. The artistic task has value to me because I am exploring new forms of art and artistic thinking, which I find rewarding.

But what of the instrumentality? In the case of the marking, it has to be done at a time where students can get the feedback at a time where they can use it and, given we have a follow-up activity of the same type for more marks, they need to get that sooner rather than later. If I leave it all until the end of the semester, it makes my students’ lives harder and mine, too, because I can’t do everything at once and every single ‘when is it coming’ query consumes more time. In the case of the art, I have no deadline but I do have a goal – a triptych work to put on the wall in August. Every print I make makes this final production easier. The production of the lino master? Intricate, close work using sharp objects and it can take hours to get a good result. It should be dull and repetitive but it’s not – but ask me to cut out 10 of the same thing or very, very similar things and I think it would be, very quickly. So, even something that I really enjoy becomes mundane when we mess with the task enough or get to the point, in this case, where we start to say “Well, why can’t a machine do this?” Rephrasing this, we get the instrumentality focus back again: “What do I gain in the future from doing this ten times if I will only do this ten times once?” And this is a valid question for our students, too. Why should they write “Hello, World” – it has most definitely and definitively been written. It’s passed on. It is novel no more. Bereft of novelty, it rests on its laurels. If we didn’t force students to write it, there is no way that this particular phrase, which we ‘owe’ to Brian Kernighan, is introducing anyone to anything that could not have a modicum of creativity added to it by saying in the manual “Please type a sentence into this point in the program and it will display it back to you.” It is an ex-program.

I love lecturing. I love giving tutorials. I will happily provide feedback in pracs. Why don’t I like marking? It’s easy to say “Well, it’s dull and repetitive” but, if I wouldn’t ask a student to undertake a task like that so why am I doing it? Look, I’m not advocating that all marking is like this but, certainly, the manual marking of particular aspects of software does tend to be dull.

Unless, of course, you start enjoying it and we can do that if we have enough freedom and flexibility to explore playful aspects. When I marked a big group of student assignments recently, I tried to write something new for each student and, this doesn’t always succeed for small artefacts with limited variability, I did manage to complement a student on their spanish variable names, provide personalised feedback to some students who had excelled and, generally, turned a 10 mark program into a place where I thought about each student personally and then (more often than not) said something unique. Yes, sometimes the same errors cropped up and the copy/paste is handy – but by engaging with the task and thinking about how much my future interactions with the students would be helped with a little investment now, the task was still a slog, but I came out of it quite pleased with the overall achievement. The task became more enjoyable because I had more flexibility but I also was required to be there to be part of the process, I was necessary. It became possible to be (professionally and carefully) playful – which is often how I approach teaching.

Any of you who are required to use standardised tests with manual marking: you already know how desperately dull the grading is and it is a grindingly dull, rubric-bound, tick/flick scenario that does nothing except consume work. It’s valuable because it’s required and money is money. Motivating? No. Any instrumentality? No, unless giving the test raises the students to the point where you get improved circumstances (personal/school) or you reduce the amount of testing required for some reason. It is, sadly, as dull for your students to undertake them, in this scenario, because they will know how it’s marked and it is not going to trigger any of Husman’s three distinguished but associated variables.

I am never saying that everything has to fun or easy, because I doubt many areas would be able to convey enough knowledge under these strictures, but providing tasks that have room to encourage motivation, develop a personal sense of task value, and that allow students to play, potentially bringing in some of their own natural enthusiasm on other areas or channeling it here, solves two thirds of the problem in getting students involved. Intentionally grounding learning in play and carefully designing materials to make this work can make things better. It also makes it easier for staff. Right now, as we handle the assignment work of the course I’m currently teaching, other discussions on the student forums includes the History of Computing, Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions, the significance of certain questions in the practical, complexity theory and we have only just stopped the spontaneous student comparison of performance at a simple genetic algorithms practical. My students are exploring, they are playing in the space of the discipline and, by doing so, are moving more deeply into a knowledge of taxonomy and lexicon within this space. I am moving from Lion Tamer to Ringmaster, which is the logical step to take as what I want is citizens who are participating because they can see value, have some level of motivation and are forming their instrumentality. If learning and exploration is fun now, then going further in this may lead to fun later – the future fun goal is enhanced by achieving tasks now. I’m not sure if this is necessarily the correct first demonstration of instrumentality, but it is a useful one!

However, it requires time for both the staff member to be able to construct and moderate such an environment, especially if you’re encouraging playful exploration of areas on public discussion forums, and the student must have enough time to be able to think about things, make plans and then to try again if they don’t pick it all up on the first go. Under strict and tight deadlines, we know the creativity can be impaired when we enforce the deadlines the wrong way, and we reduce the possibility of time for exploration and play – for students and staff.

Playing is serious business and our lives are better when we do more of it – the first enabling act of good play is scheduling that first play date and seeing how it goes. I’ve certainly found it to be helpful, to me and to my students.

The Kids are Alright (within statistical error)

Posted: April 21, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: blogging, community, data visualisation, design, education, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, reflection, thinking, tools 3 CommentsYou may have seen this quote, often (apparently inaccurately) attributed to Socrates:

“The children now love luxury; they have bad manners, contempt for authority; they show disrespect for elders and love chatter in place of exercise. Children are now tyrants, not the servants of their households. They no longer rise when elders enter the room. They contradict their parents, chatter before company, gobble up dainties at the table, cross their legs, and tyrannize their teachers.” (roughly 400BC)

Apparently this is either a paraphrase of Aristophanes or misquoted Plato – like all things attributed to Socrates, we have to remember that we don’t have his signature to any of them. However, it doesn’t really matter if Socrates said it because not only did Hesiod say something in 700BC:

“I see no hope for the future of our people if they are dependent on frivolous youth of today, for certainly all youth are reckless beyond words… When I was young, we were taught to be discreet and respectful of elders, but the present youth are exceedingly wise [disrespectful] and impatient of restraint”

And then we have Peter the Hermit in 1274AD:

“The world is passing through troublous times. The young people of today think of nothing but themselves. They have no reverence for parents or old age. They are impatient of all restraint. They talk as if they knew everything, and what passes for wisdom with us is foolishness with them. As for the girls, they are forward, immodest and unladylike in speech, behavior and dress.”

(References via the Wikiquote page of Socrates and a linked discussion page.)

Let me summarise all of this for you:

You dang kids! Get off my lawn.

As you know, I’m a facty-analysis kind of guy so I thought that, if these wise people were correct and every generation is steadily heading towards mental incapacity and moral turpitude, we should be able to model this. (As an aside, I love the word turpitude, it sounds like the state of mind a turtle reaches after drinking mineral spirits.)

So let’s do this, let’s assume that all of these people are right and that the youth are reckless, disrespectful and that this keeps happening. How do we model this?

It’s pretty obvious that the speakers in question are happy to set themselves up as people who are right, so let’s assume that a human being’s moral worth starts at 100% and that all of these people are lucky enough to hold this state. Now, since Hesiod is chronologically the first speaker, let’s assume that he is lucky enough to be actually at 100%. Now, if the kids aren’t alright, then every child born will move us away from this state. If some kids are ok, then they won’t change things. Of course, every so often we must get a good one (or Socrates’ mouthpiece and Peter the Hermit must be aliens) so there should be a case for positive improvement. But we can’t have a human who is better than 100%, work with me here, and we shall assume that at 0% we have the worst person you can think of.

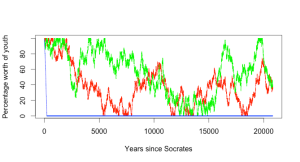

What we are now modelling is a random walk, starting at 100 and then adding some combination of -1, 0 or 1 at some regular interval. Let me cut to the chase and show you what this looks like, when modelled. I’ve assumed, for ease of modelling, that we make the assessment of the children every year and we have at most a 1 percentile point shift in that year, whatever other assumptions I made. I’ve provided three different models, one where the kids are terrible – we choose very year from no change or a negative shift. The next model is that the kids have some hope but sometimes do nothing, and we choose from an improvement, no change or steady moral decline! The final model is one where we either go up or down. Let’s look at a random walk across all three models over the span of years from 700BC to today:

As you can see, if we take the dire predictions of the next generation as true, then it is only a few hundred years before everything collapses. However, as expected, random walks over this range move around and hit a range of values. (Right now, you should look up Gambler’s Ruin to see why random walks are interesting – basically, over an infinite time, you’d expect to hit all of the values in the range from 0 to 100 an infinite number of times. This is why gamblers with small pots of money struggle against casinos with effectively infinite resources. Maths.)

But we know that the ‘everything is terrible’ model doesn’t work because both Socrates and Peter the Hermit consider themselves to be moral and both lived after the likely ‘decline to zero’ point shown in the blue line. But what would happen over longer timeframes? Let’s look at 20,000 and 200,000 years respectively. (These are separately executed random walks so the patterns will be different in each graph.)

What should be apparent, even with this rather pedantic exploration of what was never supposed to be modelled is that, even if we give credence to these particular commentators and we accept that there is some actual change that is measurable and shows an improvement or decline between generations, the negative model doesn’t work. The longer we run this, the more it will look like the noise that it is – and that is assuming that these people were right in the first place.

Personally, I think that the kids of this generation are pretty much the same as the one before, with some different adaptation to technology and societal mores. Would I have wasted time in lectures Facebooking if I had the chance? Well, I wasted it doing everything else so, yes, probably. (Look around your next staff meeting to see how many people are checking their mail. This is a technological shift driven by capability, not a sign of accelerating attention deficit.) Would I have spent tons of times playing games? Would I? I did! They were just board, role-playing and simpler computer games. The kids are alright and you can see that from the graphs – within statistical error.

Every time someone tells me that things are different, but it’s because the students are not of the same calibre as the ones before… well, I look at these quotes over the past 2,500 and I wonder.

And I try to stay off their lawn.

SIGCSE 2013: Special Session on Designing and Supporting Collaborative Learning Activities

Posted: March 31, 2013 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, reflection, resources, sigcse, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design Leave a commentKatrina and I delivered a special session on collaborative learning activities, focused on undergraduates because that’s our area of expertise. You can read the outline document here. We worked together on the underlying classroom activities and have both implemented these techniques but, in this session, Katrina did most of the presenting and I presented the collaborative assessment task examples, with some facilitation.

The trick here is, of course, to find examples that are both effective as teaching tools and are effective as examples. The approach I chose to take was to remind everyone in the room of what the most important aspects were to making this work with students and I did this by deliberately starting with a bad example. This can be a difficult road to walk because, when presenting a bad example, you need to convince everyone that your choice was deliberate and that you actually didn’t just stuff things up.

My approach was fairly simple. Break people into groups, based on where they were currently sitting, and then I immediately went into the question, which had been tailored for the crowd and for my purposes:

“I want you to talk about the 10 things that you’re going to do in the next 5 years to make progress in your career and improve your job performance.”

And why not? Everyone in the room was interested in education and, most likely, had a job at a time when it’s highly competitive and hard to find or retain work – so everyone has probably thought about this. It’s a fair question for this crowd.

Well, it would be, if it wasn’t so anxiety inducing. Katrina and I both observed a sea of frozen faces as we asked a question that put a large number of participants on the spot. And the reason I did this was to remind everyone that anxiety impairs genuine participation and willingness to engage. There were a large number of frozen grins with darting eyes, some nervous mumbles and a whole lot of purposeless noise, with the few people who were actually primed to answer that question starting to lead off.

I then stopped the discussion immediately. “What was wrong with that?” I asked the group.

Well, where do we start? Firstly, it’s an individual activity, not a collaborative activity – there’s no incentive or requirement for discussion, groupwork or anything like that. Secondly, while we might expect people to be able to answer this, it is a highly charged and personal areas, and you may not feel comfortable discussing your five year plan with people that you don’t know. Thirdly, some people know that they should be able to answer this (or at least some supervisors will expect that they can) but they have no real answer and their anxiety will not only limit their participation but it will probably stop them from listening at all while they sweat their turn. Finally, there is no point to this activity – why are we doing this? What are we producing? What is the end point?

My approach to collaborative activity is pretty simple and you can read any amount of Perry, Dickinson, Hamer et al (and now us as well) to look at relevant areas and Contributing Student Pedagogy, where students have a reason to collaborate and we manage their developmental maturity and their roles in the activity to get them really engaged. Everyone can have difficulties with authority and recognising whether someone is making enough contribution to a discussion to be worth their time – this is not limited to students. People, therefore, have to believe that the group they are in is of some benefit to them.

So we stepped back. I asked everyone to introduce themselves, where they came from and give a fact about their current home that people might not know. Simple task, everyone can do it and the purpose was to tell your group something interesting about your home – clear purpose, as well. This activity launched immediately and was going so well that, when I tried to move it on because the sound levels were dropping (generally a good sign that we’re reaching a transition), some groups asked if they could keep going as they weren’t quite finished. (Monitoring groups spread over a large space can be tricky but, where the activity is working, people will happily let you know when they need more time.) I was able to completely stop the first activity and nobody wanted me to continue. The second one, where people felt that they could participate and wanted to say something, needed to keep going.

Having now put some faces to names, we then moved to a simple exercise of sharing an interesting teaching approach that you’d tried recently or seen at the conference and it’s important to note the different comfort levels we can accommodate with this – we are sharing knowledge but we give participants the opportunity to share something of themselves or something that interest them, without the burden of ownership. Everyone had already discovered that everyone in the group had some areas of knowledge, albeit small, that taught them something new. We had started to build a group where participants valued each other’s contribution.

I carried out some roaming facilitation where I said very little, unless it was needed. I sat down with some groups, said ‘hi’ and then just sat back while they talked. I occasionally gave some nodded or attentive feedback to people who looked like they wanted to speak and this often cued them into the discussion. Facilitation doesn’t have to be intrusive and I’m a much bigger fan of inclusiveness, where everyone gets a turn but we do it through non-verbal encouragement (where that’s possible, different techniques are required in a mixed-ability group) to stay out of the main corridor of communication and reduce confrontation. However, by setting up the requirement that everyone share and by providing a task that everyone could participate in, my need to prod was greatly reduced and the groups mostly ran themselves, with the roles shifting around as different people made different points.

We covered a lot of the underlying theory in the talk itself, to discuss why people have difficulty accepting other views, to clarify why role management is a critical part of giving people a reason to get involved and something to do in the conversation. The notion that a valid discursive role is that of the supporter, to reinforce ideas from the proposer, allows someone to develop their confidence and critically assess the idea, without the burden of having to provide a complex criticism straight away.

At the end, I asked for a show of hands. Who had met someone knew? Everyone. Who had found out something they didn’t know about other places? Everyone. Who had learned about a new teaching technique that they hadn’t known before. Everyone.

My one regret is that we didn’t do this sooner because the conversation was obviously continuing for some groups and our session was, sadly, on the last day. I don’t pretend to be the best at this but I can assure you that any capability I have in this kind of activity comes from understanding the theory, putting it into practice, trying it, trying it again, and reflecting on what did and didn’t work.

I sometimes come out of a lecture or a collaborative activity and I’m really not happy. It didn’t gel or I didn’t quite get the group going as I wanted it to – but this is where you have to be gentle on yourself because, if you’re planning to succeed and reflecting on the problems, then steady improvement is completely possible and you can get more comfortable with passing your room control over to the groups, while you move to the facilitation role. The more you do it, the more you realise that training your students in role fluidity also assists them in understanding when you have to be in control of the room. I regularly pass control back and forward and it took me a long time to really feel that I wasn’t losing my grip. It’s a practice thing.

It was a lot of fun to give the session and we spent some time crafting the ‘bad example’, but let me summarise what the good activities should really look like. They must be collaborative, inclusive, achievable and obviously beneficial. Like all good guidelines there are times and places where you would change this set of characteristics, but you have to know your group well to know what challenges they can tolerate. If your students are more mature, then you push out into open-ended tasks which are far harder to make progress in – but this would be completely inappropriate for first years. Even in later years, being able to make some progress is more likely to keep the group going than a brick wall that stops you at step 1. But, let’s face it, your students need to know that working in that group is not only not to their detriment, but it’s beneficial. And the more you do this, the better their groupwork and collaboration will get – and that’s a big overall positive for the graduates of the future.

To everyone who attended the session, thank you for the generosity and enthusiasm of your participation and I’m catching up on my business cards in the next weeks. If I promised you an e-mail, it will be coming shortly.

SIGCSE 2013: The Revolution Will Be Televised, Perspectives on MOOC Education

Posted: March 17, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, community, education, educational research, ethics, Generation Why, higher education, learning, measurement, moocs, sigcse, teaching, teaching approaches, tools 4 CommentsLong time between posts, I realise, but I got really, really unwell in Colorado and am still recovering from it. I attended a lot of interesting sessions at SIGCSE 2013, and hopefully gave at least one of them, but the first I wanted to comment on was a panel with Mehram Sahami, Nick Parlante, Fred Martin and Mark Guzdial, entitled “The Revolution Will Be Televised, Perspectives on MOOC Education”. This is, obviously, a very open area for debate and the panelists provided a range of views and a lot of information.

Mehram started by reminding the audience that we’ve had on-line and correspondence courses for some time, with MIT’s OpenCourseWare (OCW) streaming video from the 1990s and Stanford Engineering Everywhere (SEE) starting in 2008. The SEE lectures were interesting because viewership follows a power law relationship: the final lecture has only 5-10% of the views of the first lecture. These video lectures were being used well beyond Stanford, augmenting AP courses in the US and providing entire lecture series in other countries. The videos also increased engagement and the requests that came in weren’t just about the course but were more general – having a face and a name on the screen gave people someone to interact with. From Mehram’s perspective, the challenges were: certification and credit, increasing the richness of automated evaluation, validated peer evaluation, and personalisation (or, as he put it, in reality mass customisation).

Nick Parlante spoke next, as an unashamed optimist for MOOC, who has the opinion that all the best world-changing inventions are cheap, like the printing press, arabic numerals and high quality digital music. These great ideas spread and change the world. However, he did state that he considered artisinal and MOOC education to be very different: artisinal education is bespoke, high quality and high cost, where MOOCs are interesting for the massive scale and, while they could never replace artisinal, they could provide education to those who could not get access to artisinal.

It was at this point that I started to twitch, because I have heard and seen this argument before – the notion that MOOC is better than nothing, if you can’t get artisinal. The subtext that I, fairly or not, hear at this point is the implicit statement that we will never be able to give high quality education to everybody. By having a MOOC, we no longer have to say “you will not be educated”, we can say “you will receive some form of education”. What I rarely hear at this point is a well-structured and quantified argument on exactly how much quality slippage we’re tolerating here – how educational is the alternative education?

Nick also raised the well-known problems of cheating (which is rampant in MOOCs already before large-scale fee paying has been introduced) and credentialling. His section of the talk was long on optimism and positivity but rather light on statistics, completion rates, and the kind of evidence that we’re all waiting to see. Nick was quite optimistic about our future employment prospects but I suspect he was speaking on behalf of those of us in “high-end” old-school schools.

I had a lot of issues with what Nick said but a fair bit of it stemmed from his examples: the printing press and digital music. The printing press is an amazing piece of technology for replicating a written text and, as replication and distribution goes, there’s no doubt that it changed the world – but does it guarantee quality? No. The top 10 books sold in 2012 were either Twilight-derived sadomasochism (Fifty Shades of Unncessary) or related to The Hunger Games. The most work the printing presses were doing in 2012 was not for Thoreau, Atwood, Byatt, Dickens, Borges or even Cormac McCarthy. No, the amazing distribution mechanism was turning out copy after copy of what could be, generously, called popular fiction. But even that’s not my point. Even if the printing presses turned out only “the great writers”, it would be no guarantee of an increase in the ability to write quality works in the reading populace, because reading and writing are different things. You don’t have to read much into constructivism to realise how much difference it makes when someone puts things together for themselves, actively, rather than passively sitting through a non-interactive presentation. Some of us can learn purely from books but, obviously, not all of us and, more importantly, most of us don’t find it trivial. So, not only does the printing press not guarantee that everything that gets printed is good, even where something good does get printed, it does not intrinsically demonstrate how you can take the goodness and then apply it to your own works. (Why else would there be books on how to write?) If we could do that, reliability and spontaneously, then a library of great writers would be all you needed to replace every English writing course and editor in the world. A similar argument exists for the digital reproduction of music. Yes, it’s cheap and, yes, it’s easy. However, listening to music does not teach you to how write music or perform on a given instrument, unless you happen to be one of the few people who can pick up music and instrumentation with little guidance. There are so few of the latter that we call them prodigies – it’s not a stable model for even the majority of our gifted students, let alone the main body.

Fred Martin spoke next and reminded us all that weaker learners just don’t do well in the less-scaffolded MOOC environment. He had used MOOC in a flipped classroom, with small class sizes, supervision and lots of individual discussion. As part of this blended experience, it worked. Fred really wanted some honest figures on who was starting and completing MOOCs and was really keen that, if we were to do this, that we strive for the same quality, rather than accepting that MOOCs weren’t as good and it was ok to offer this second-tier solution to certain groups.

Mark Guzdial then rounded out the panel and stressed the role of MOOCs as part of a diverse set of resources, but if we were going to do that then we had to measure and report on how things had gone. MOOC results, right now, are interesting but fundamentally anecdotal and unverified. Therefore, it is too soon to jump into MOOC because we don’t yet know if it will work. Mark also noted that MOOCs are not supporting diversity yet and, from any number of sources, we know that many-to-one (the MOOC model) is just not as good as 1-to-1. We’re really not clear if and how MOOCs are working, given how many people who do complete are actually already degree holders and, even then, actual participation in on-line discussion is so low that these experienced learners aren’t even talking to each other very much.

It was an interesting discussion and conducted with a great deal of mutual respect and humour, but I couldn’t agree more with Fred and Mark – we haven’t measured things enough and, despite Nick’s optimism, there are too many unanswered questions to leap in, especially if we’re going to make hard-to-reverse changes to staffing and infrastructure. It takes 20 years to train a Professor and, if you have one that can teach, they can be expensive and hard to maintain (with tongue firmly lodged in cheek, here). Getting rid of one because we have a promising new technology that is untested may save us money in the short term but, if we haven’t validated the educational value or confirmed that we have set up the right level of quality, a few years now from now we might discover that we got rid of the wrong people at the wrong time. What happens then? I can turn off a MOOC with a few keystrokes but I can’t bring back all of my seasoned teachers in a timeframe less than years, if not decades.

I’m with Mark – the resource promise of MOOCs is enormous and they are part of our future. Are they actually full educational resources or courses yet? Will they be able to bring education to people that is a first-tier, high quality experience or are we trapped in the same old educational class divisions with a new name for an old separation? I think it’s too soon to tell but I’m watching all of the new studies with a great deal of interest. I, too, am an optimist but let’s call me a cautious one!

Expressiveness and Ambiguity: Learning to Program Can Be Unnecessarily Hard

Posted: January 23, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, collaboration, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools Leave a commentOne of the most important things to be able to do in any profession is to think as a professional. This is certainly true of Computer Science, because we have to spend so much time thinking as a Computer Scientist would think about how the machine will interpret our instructions. For those who don’t program, a brief quiz. What is the value of the next statement?

What is 3/4?

No doubt, you answered something like 0.75 or maybe 75% or possibly even “three quarters”? (And some of you would have said “but this statement has no intrinsic value” and my heartiest congratulations to you. Now go off and contemplate the Universe while the rest of us toil along on the material plane.) And, not being programmers, you would give me the same answer if I wrote:

What is 3.0/4.0?

Depending on the programming language we use, you can actually get two completely different answers to this apparently simple question. 3/4 is often interpreted by the computer to mean “What is the result if I carry out integer division, where I will only tell you how many times the denominator will go into the numerator as a whole number, for 3 and 4?” The answer will not be the expected 0.75, it will be 0, because 4 does not go into 3 – it’s too big. So, again depending on programming language, it is completely possible to ask the computer “is 3/4 equivalent to 3.0/4.0?” and get the answer ‘No’.

This is something that we have to highlight to students when we are teaching programming, because very few people use integer division when they divide one thing by another – they automatically start using decimal points. Now, in this case, the different behaviour of the ‘/’ is actually exceedingly well-defined and is not all ambiguous to the computer or to the seasoned programmer. It is, however, nowhere near as clear to the novice or casual observer.

I am currently reading Stephen Ramsay’s excellent “Reading Machines: Towards an Algorithmic Criticism” and it is taking me a very long time to read an 80 page book. Why? Because, to avoid ambiguity and to be as expressive and precise as possible, he has used a number of words and concepts with which I am unfamiliar or that I have not seen before. I am currently reading his book with a web browser and a dictionary because I do not have a background in literary criticism but, once I have the building blocks, I can understand his argument. In other words, I am having to learn a new language in order to read a book for that new language community. However, rather than being irked that “/” changes meaning depending on the company it keeps, I am happy to learn the new terms and concepts in the space that Ramsay describes, because it is adding to my ability to express key concepts, without introducing ambiguous shadings of language over things that I already know. Ramsay is not, for example, telling me that “book” no longer means “book” when you place it inside parentheses. (It is worth noting that Ramsay discusses the use of constraint as a creative enhancer, a la Oulipo, early on in the book and this is a theme for another post.)

The usual insult at this point is to trot out the accusation of jargon, which is as often a statement that “I can’t be bothered learning this” than it is a genuine complaint about impenetrable prose. In this case, the offender in my opinion is the person who decided to provide an invisible overloading of the “/” operator to mean both “division” and “integer division”, as they have required us to be aware of a change in meaning that is not accompanied by a change in syntax. While this isn’t usually a problem, spoken and written languages are full of these things after all, in the computing world it forces the programmer to remember that “/” doesn’t always mean “/” and then to get it the right way around. (A number of languages solve this problem by providing a distinct operator – this, however, then adds to linguistic complexity and rather than learning two meanings, you have to learn two ‘words’. Ah, no free lunch.) We have no tone or colour in mainstream programming languages, for a whole range of good computer grammar reasons, but the absence of the rising tone or rising eyebrow is sorely felt when we encounter something that means two different things. The net result is that we tend to use the same constructs to do the same thing because we have severe limitations upon our expressivity. That’s why there are boilerplate programmers, who can stitch together a solution from things they have already seen, and people who have learned how to be as expressive as possible, despite most of these restrictions. Regrettably, expressive and innovative code can often be unreadable by other people because of the gymnastics required to reach these heights of expressiveness, which is often at odds with what the language designers assumed someone might do.

We have spent a great deal of effort making computers better at handling abstract representations, things that stand in for other (real) things. I can use a name instead of a number and the computer will keep track of it for me. It’s important to note that writing int i=0; is infinitely preferable to typing “0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000” into the correct memory location and then keeping that (rather large number) address written on a scrap of paper. Abstraction is one of the fundamental tools of modern programming, yet we greatly limit expressiveness in sometimes artificial ways to reduce ambiguity when, really, the ambiguity does seem a little artificial.

One of the nastiest potential ambiguities that shows up a lot is “what do we mean by ‘equals'”. As above, we already know that many languages would not tell you that “3/4 equals 3.0/4.0” because both mathematical operations would be executed and 0 is not the same as 0.75. However, the equivalence operator is often used to ask so many different questions: “Do these two things contain the same thing?”, “Are these two things considered to be the same according to the programmer?” and “Are these two things actually the same thing and stored in the same place in memory?”

Generally, however, to all of these questions, we return a simple “True” or “False”, which in reality reflects neither the truth nor the falsity of the situation. What we are asking, respectively, is “Are the contents of these the same?” to which the answer is “Same” or “Different”. To the second, we are asking if the programmer considers them to be the same, in which case the answer is really “Yes” or “No” because they could actually be different, yet not so different that the programmer needs to make a big deal about it. Finally, when we are asking if two references to an object actually point to the same thing, we are asking if they are in the same location or not.

There are many languages that use truth values, some of them do it far better than others, but unless we are speaking and writing in logical terms, the apparent precision of the True/False dichotomy is inherently deceptive and, once again, it is only as precise as it has been programmed to be and then interpreted, based on the knowledge of programmer and reader. (The programming language Haskell has an intrinsic ability to say that things are “Undefined” and to then continue working on the problem, which is an obvious, and welcome, exception here, yet this is not a widespread approach.) It is an inherent limitation on our ability to express what is really happening in the system when we artificially constrain ourselves in order to (apparently) reduce ambiguity. It seems to me that we have reduced programmatic ambiguity, but we have not necessarily actually addressed the real or philosophical ambiguity inherent in many of these programs.

More holiday musings on the “Python way” and why this is actually an unreasonable demand, rather than a positive feature, shortly.

The Limits of Expressiveness: If Compilers Are Smart, Why Are We Doing the Work?

Posted: January 23, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: 'pataphysics, collaboration, community, curriculum, data visualisation, design, education, educational problem, higher education, principles of design, programming, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools 2 CommentsI am currently on holiday, which is “Nick shorthand” for catching up on my reading, painting and cat time. Recently, my interests in my own discipline have widened and I am precariously close to that terrible state that academics sometimes reach when they suddenly start uttering words like “interdisciplinary” or “big tent approach”. Quite often, around this time, the professoriate will look at each other, nod, and send for the nice people with the butterfly nets. Before they arrive and cart me away, I thought I’d share some of the reading and thinking I’ve been doing lately.

My reading is a little eclectic, right now. Next to Hooky’s account of the band “Joy Division” sits Dennis Wheatley’s “They Used Dark Forces” and next to that are four other books, which are a little more academic. “Reading Machines: Towards an Algorithmic Criticism” by Stephen Ramsay; “Debates in the Digital Humanities” edited by Matthew Gold; “10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); : GOTO 10” by Montfort et al; and “‘Pataphysics: A Useless Guide” by Andrew Hugill. All of these are fascinating books and, right now, I am thinking through all of these in order to place a new glass over some of my assumptions from within my own discipline.

“10 PRINT CHR$…” is an account of a simple line of code from the Commodore 64 Basic language, which draws diagonal mazes on the screen. In exploring this, the authors explore fundamental aspects of computing and, in particular, creative computing and how programs exist in culture. Everything in the line says something about programming back when the C-64 was popular, from the use of line numbers (required because you had to establish an execution order without necessarily being able to arrange elements in one document) to the use of the $ after CHR, which tells both the programmer and the machine that what results from this operation is a string, rather than a number. In many ways, this is a book about my own journey through Computer Science, growing up with BASIC programming and accepting its conventions as the norm, only to have new and strange conventions pop out at me once I started using other programming languages.

Rather than discuss the other books in detail, although I recommend all of them, I wanted to talk about specific aspects of expressiveness and comprehension, as if there is one thing I am thinking after all of this reading, it is “why aren’t we doing this better”? The line “10 PRINT CHR$…” is effectively incomprehensible to the casual reader, yet if I wrote something like this:

do this forever

pick one of “/” or “\” and display it on the screen

then anyone who spoke English (which used to be a larger number than those who could read programming languages but, honestly, today I’m not sure about that) could understand what was going to happen but, not only could they understand, they could create something themselves without having to work out how to make it happen. You can see language like this in languages such as Scratch, which is intended to teach programming by providing an easier bridge between standard language and programming using pre-constructed blocks and far more approachable terms. Why is it so important to create? One of the debates raging in Digital Humanities at the moment, at least according to my reading, is “who is in” and “who is out” – what does it take to make one a digital humanist? While this used to involve “being a programmer”, it is now considered reasonable to “create something”. For anyone who is notionally a programmer, the two are indivisible. Programs are how we create things and programming languages are the form that we use to communicate with the machines, to solve the problems that we need solved.

When we first started writing programs, we instructed the machines in simple arithmetic sequences that matched the bit patterns required to ensure that certain memory locations were processed in a certain way. We then provided human-readable shorthand, assembly language, where mnemonics replaced numbers, to make it easier for humans to write code without error. “20” became “JSR” in 6502 assembly code, for example, yet “JSR” is as impenetrably occulted as “20” unless you learn a language that is not actually a language but a compressed form of acronym. Roll on some more years and we have added pseudo-English over the top: GOSUB in Basic and the use of parentheses to indicate function calls in other languages.

However, all I actually wanted to do was to make the same thing happen again, maybe with some minor changes to what it was working on. Think of a sub-routine (method, procedure or function, if we’re being relaxed in our terminology) and you may as well think of a washing machine. It takes in something and combines it with a determined process, a machine setting, powders and liquids to give you the result you wanted, in this case taking in dirty clothes and giving back clean ones. The execution of a sub-routine is identical to this but can you see the predictable familiarity of the washing machine in JSR FE FF?

If you are familiar with ‘Pataphysics, or even “Ubu Roi” the most well-known of Jarry’s work, you may be aware of the pataphysician’s fascination with the spiral – le Grand Gidouille. The spiral, once drawn, defines not only itself but another spiral in the negative space that it contains. The spiral is also a natural way to think about programming because a very well-used programming language construct, the for loop, often either counts up to a value or counts down. It is not uncommon for this kind of counting loop to allow us to advance from one character to the next in a text of some sort. When we define a loop as a spiral, we clearly state what it is and what it is not – it is not retreading old ground, although it may always spiral out towards infinity.

However, for maximum confusion, the for loop may iterate a fixed number of times but never use the changing value that is driving it – it is no longer a spiral in terms of its effect on its contents. We can even write a for loop that goes around in a circle indefinitely, executing the code within it until it is interrupted. Yet, we use the same keyword for all of these.

In English, the word “get” is incredibly overused. There are very few situations when another verb couldn’t add more meaning, even in terms of shade, to the situation. Using “get” forces us, quite frequently, to do more hard work to achieve comprehension. Using the same words for many different types of loop pushes load back on to us.

What happens is that when we write our loop, we are required to do the thinking as to how we want this loop to work – although Scratch provides a forever, very few other languages provide anything like that. To loop endlessly in C, we would use while (true) or for (;;), but to tell the difference between a loop that is functioning as a spiral, and one that is merely counting, we have to read the body of the loop to see what is going on. If you aren’t a programmer, does for(;;) give you any inkling at all as to what is going on? Some might think “Aha, but programming is for programmers” and I would respond with “Aha, yes, but becoming a programmer requires a great deal of learning and why don’t we make it simpler?” To which the obvious riposte is “But we have special languages which will do all that!” and I then strike back with “Well, if that is such a good feature, why isn’t it in all languages, given how good modern language compilers are?” (A compiler is a program that turns programming languages into something that computers can execute – English words to byte patterns effectively.)

In thinking about language origins, and what we are capable of with modern compilers, we have to accept that a lot of the heavy lifting in programming is already being done by modern, optimising, compilers. Years ago, the compiler would just turn your instructions into a form that machines could execute – with no improvement. These days, put something daft in (like a loop that does nothing for a million iterations), and the compiler will quietly edit it out. The compiler will worry about optimising your storage of information and, sometimes, even help you to reduce wasted use of memory (no, Java, I’m most definitely not looking at you.)

So why is it that C++ doesn’t have a forever, a do 10 times, or a spiral to 10 equivalent in there? The answer is complex but is, most likely, a combination of standards issues (changing a language standard is relatively difficult and requires a lot of effort), the fact that other languages do already do things like this, the burden of increasing compiler complexity to handle synonyms like this (although this need not be too arduous) and, most likely, the fact that I doubt that many people would see a need for it.

In reading all of these books, and I’ll write more on this shortly, I am becoming increasingly aware that I tolerate a great deal of limitation in my ability to solve problems using programming languages. I put up with having my expressiveness reduced, with taking care of some unnecessary heavy lifting in making things clear to the compiler, and I occasionally even allow the programming language to dictate how I write the words on the page itself – not just syntax and semantics (which are at least understandably, socially and technically) but the use of blank lines, white space and end of lines.

How are we expected to be truly creative if conformity and constraint are the underpinnings of programming? Tomorrow, I shall write on the use of constraint as a means of encouraging creativity and why I feel that what we see in programming is actually limitation, rather than a useful constraint.

WordPress Still Don’t Quite Get It

Posted: December 31, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, blogging, education, higher education, thinking, tools Leave a commentSome time ago, I logged a report to WordPress that one of their ‘incentive’ messages for completing and posting a blog post was a highly dismissive Capote quote about Kerouac’s writing of “On the Road” – “That’s not writing, that’s typing”. I felt that this was not the kind of thing that you said to someone as an incentive and, nicely, the people who handled my comment appeared to agree and I haven’t seen it since.

Today they sent me their “Your Year in Review” link which gave me a prettied-up, but not overly informative, set of aggregated statistics for 2012. This one stuck out:

“In 2012, there were 438 new posts, not bad for the first year!”

Not bad? I posted every 20 hours on average across the year and that’s not bad???

I know what they’re trying to say but, seriously, their automated encouragement software needs some work. Of course, the scary question is: what does WordPress consider to be good in terms of posting count? Every 10 hours? Every 5 hours?

Seriously, WordPress people, please start thinking about the throwaway language that you are using to pretend that you know what we’re doing. We are all happily using your site – don’t let bad scripting and automated pseudo-encouragement undo all of the cool things that we can do here!

Thanks for the exam – now I can’t help you.

Posted: December 31, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, tools, universal principles of design, vygotsky, workload 1 CommentI have just finished marking a pile of examinations from a course that I co-taught recently. I haven’t finalised the marks but, overall, I’m not unhappy with the majority of the results. Interestingly, and not overly surprisingly, one of the best answered sections of the exam was based on a challenging essay question I set as an assignment. The question spans many aspects of the course and requires the student to think about their answer and link the knowledge – which most did very well. As I said, not a surprise but a good reinforcement that you don’t have to drill students in what to say in the exam, but covering the requisite knowledge and practising the right skills is often helpful.

However, I don’t much like marking exams and it doesn’t come down to the time involved, the generally dull nature of the task or the repetitive strain injury from wielding a red pen in anger, it comes down to the fact that, most of the time, I am marking the student’s work at a time when I can no longer help him or her. Like most exams at my Uni, this was the terminal examination for the course, worth a substantial amount of the final marks, and was taken some weeks after teaching finished. So what this means is that any areas I identify for a given student cannot now be corrected, unless the student chooses to read my notes in the exam paper or come to see me. (Given that this campus is international, that’s trickier but not impossible thanks to the Wonders of Skypenology.) It took me a long time to work out exactly why I didn’t like marking, but when I did, the answer was obvious.

I was frustrated that I couldn’t actually do my job at one of the most important points: when lack of comprehension is clearly identified. If I ask someone a question in the classroom, on-line or wherever, and they give me an answer that’s not quite right, or right off base, then we can talk about it and I can correct the misunderstanding. My job, after all, is not actually passing or failing students – it’s about knowledge, the conveyance, construction and quality management thereof. My frustration during exam marking increases with every incomplete or incorrect answer I read, which illustrates that there is a section of the course that someone didn’t get. I get up in the morning with the clear intention of being helpful towards students and, when it really matters, all I can do is mark up bits of paper in red ink.

Quickly, Jones! Construct a valid knowledge framework! You’re in a group environment! Vygotsky, man, Vygotsky!

A student who, despite my sweeping, and seeping, liquid red ink of doom, manages to get a 50 Passing grade will not do the course again – yet this mark pretty clearly indicates that roughly half of the comprehension or participation required was not carried out to the required standard. Miraculously, it doesn’t matter which half of the course the student ‘gets’, they are still deemed to have attained the knowledge. (An interesting point to ponder, especially when you consider that my colleagues in Medicine define a Pass at a much higher level and in far more complicated ways than a numerical 50%, to my eternal peace of mind when I visit a doctor!) Yet their exam will still probably have caused me at least some gnashing of teeth because of points missed, pointless misstatement of the question text, obscure song lyrics, apologies for lack of preparation and the occasional actual fact that has peregrinated from the place where it could have attained marks to a place where it will be left out in the desert to die, bereft of the life-giving context that would save it from such an awful fate.

Should we move the exams earlier and then use this to guide the focus areas for assessment in order to determine the most improvement and develop knowledge in the areas in most need? Should we abandon exams entirely and move to a continuous-assessment competency based system, where there are skills and knowledge that must be demonstrated correctly and are practised until this is achieved? We are suffering, as so many people have observed before, from overloading the requirement to grade and classify our students into neatly discretised performance boxes onto a system that ultimately seeks to identify whether these students have achieved the knowledge levels necessary to be deemed to have achieved the course objectives. Should we separate competency and performance completely? I have sketchy ideas as to how this might work but none that survive under the blow-torches of GPA requirements and resource constraints.

Obviously, continuous assessment (practicals, reports, quizzes and so on) throughout the semester provide a very valuable way to identify problems but this requires good, and thorough, course design and an awareness that this is your intent. Are we premature in treating the exam as a closing-off line on the course? Do we work on that the same way that we do any assignment? You get feedback, a mark and then more work to follow-up? If we threw resourcing to the wind, could we have a 1-2 week intensive pre-semester program that specifically addressed those issues that students failed to grasp on their first pass? Congratulations, you got 80%, but that means that there’s 20% of the course that we need to clarify? (Those who got 100% I’ll pay to come back and tutor, because I like to keep cohorts together and I doubt I’ll need to do that very often.)

There are no easy answers here and shooting down these situations is very much in the fish/barrel plane, I realise, but it is a very deeply felt form of frustration that I am seeing the most work that any student is likely to put in but I cannot now fix the problems that I see. All I can do is mark it in red ink with an annotation that the vast majority will never see (unless they receive the grade of 44, 49, 64, 74 or 84, which are all threshold-1 markers for us).

Ah well, I hope to have more time in 2013 so maybe I can mull on this some more and come up with something that is better but still workable.

Thinking about teaching spaces: if you’re a lecturer, shouldn’t you be lecturing?

Posted: December 30, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design, vygotsky Leave a commentI was reading a comment on a philosophical post the other day and someone wrote this rather snarky line:

He’s is a philosopher in the same way that (celebrity historian) is a historian – he’s somehow got the job description and uses it to repeat the prejudices of his paymasters, flattering them into thinking that what they believe isn’t, somehow, ludicrous. (Grangousier, Metafilter article 123174)

Rather harsh words in many respects and it’s my alteration of the (celebrity historian)’s name, not his, as I feel that his comments are mildy unfair. However, the point is interesting, as a reflection upon the importance of job title in our society, especially when it comes to the weighted authority of your words. From January the 1st, I will be a senior lecturer at an Australian University and that is perceived differently where I am. If I am in the US, I reinterpret this title into their system, namely as a tenured Associate Professor, because that’s the equivalent of what I am – the term ‘lecturer’ doesn’t clearly translate without causing problems, not even dealing with the fact that more lecturers in Australia have PhDs, where many lecturers in the US do not. But this post isn’t about how people necessarily see our job descriptions, it’s very much about how we use them.

In many respects, the title ‘lecturer’ is rather confusing because it appears, like builder, nurse or pilot, to contain the verb of one’s practice. One of the big changes in education has been the steady acceptance of constructivism, where the learners have an active role in the construction of knowledge and we are facilitating learning, in many ways, to a greater extent than we are teaching. This does not mean that teachers shouldn’t teach, because this is far more generic than the binding of lecturers to lecturing, but it does challenge the mental image that pops up when we think about teaching.

If I asked you to visualise a classroom situation, what would you think of? What facilities are there? Where are the students? Where is the teacher? What resources are around the room, on the desks, on the walls? How big is it?

Take a minute to do just this and make some brief notes as to what was in there. Then come back here.

It’s okay, I’ll still be here!

Three more – for various definitions of three.

Posted: December 29, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, blogging, education, higher education, resources, thinking, tools Leave a commentI have three more posts to make to complete my ‘year of daily posts’ – and this one doesn’t count, you’ll either be pleased or saddened to hear. I’m still torn as to when and how these will be written. I prefer the spontaneity of making the post on the day but I am very tempted by the thought of sitting around tomorrow morning to put the remaining two (by then) in the bag.

I’ll be very interested to see how much I will post after this is over. I may take Gas station without pump’s approach and publish a similar or greater number of words in a less scheduled way or I may fall completely silent. Right now I have no idea at all, which is fun and a bit scary at the same time, like almost all interesting things.

I’ve seen my fair share of abandoned blogs – you know the ones “Here is where I will detail my travels through my PhD” and the last post was back in 2006, it was only the third post and it amounted to “my brain, it hurts”. But life gets in the way and these blogs are the same as the diaries, started on January 1st, that start with “Wow, here’s my yearly diary! Every day I’m going to write something positive!” and wind up, a week later, as drink coasters or propping up the wonky sofa in the study. Life gets in the way.

Death gets in the way, too. I was reading someone’s LiveJournal years ago when they were diagnosed with cancer and the journal continues until their (far too early) death, with the final reflections of that person’s life taking place in other LJs, visible as a permanent artefact. I reread that LiveJournal, from first to last, earlier this year, to remind myself of a person who I had only known through this mechanism and, even knowing what the ending was going to be, the post where she announces that the test results had come back, and that it was cancer, shocked and upset me, almost to the point of throwing up. This vibrant, excited person, deeply in love with someone and working through all of the bits and pieces that happens when you and the person you love are in different countries, no longer updates their LiveJournal but it is still there. I have too many of these dormant LiveJournals on my list now. Death gets in the way, too.

This whole year, the good, the bad, the thoughtful, the preachy, the plain dumb and ill-informed, will stay here until this data corpus fries or the company gets sold to someone who wants to charge money for access or some such, but while it does that, it will reach more people than any other form of small-scale self-publishing has every achieved up until now. And while I have made some mistakes, it’s wrong to remove them just because I was wrong, as long as I’ve corrected them or noted where they should be corrected to be right.

This has been a part of my life. I wonder what role it will have from January 1st, 2013?