5 Things I would Like My Students to Be Able to Perceive

Posted: January 25, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, assumptions, authenticity, blogging, curriculum, education, ethics, higher education, perception, privilege, student, student perspective, thinking, tone Leave a commentOur students will go out into the world and will be exposed to many things but, if we have done our job well, then they will not just be pushed around by the pressure of the events that they witness, but they will be able to hold their ground and perceive what is really going on, to place their own stamp on the world.

I don’t tell my students how to think, although I know that it’s a commonly held belief that everyone at a Uni tries to shape the political and developmental thought of their students, I just try to get them to think. This is probably going to have the side effect of making them thoughtful, potentially even critical of things that don’t make sense, and I realise that this is something that not everybody wants from junior citizens. But that’s my job.

Here is a list of five things that I think I’d like a thoughtful person to be able to perceive. It’s not the definitive five or the perfect five but these are the ones that I have today.

- It would be nice if people were able to reliably tell the difference between 1/3 and 1/4 and understand that 1/3 is larger than 1/4. Being able to work out the odds of things (how likely they are) require you to be able to look at two things that are smaller than one and get them in the right order so you can say “this is more likely than that”. Working on percentages can make it easier but this requires people to do division, rather than just counting things and showing the fraction.But I’d like my students to be able to perceive how this can be a fundamental misunderstanding that means that some people can genuinely look at comparative probabilities and not be able to work out that this simple mathematical comparison is valid. And I’d like them to be able to think about how to communicate this to help people understand.

- A perceptive person would be able to spot when something isn’t free. There are many people who go into casinos and have a lot of fun gambling, eating very cheap or unlimited food, staying in cheap hotels and think about what a great deal it is. However, every game you play in a casino is designed so that casinos do not make a loss – but rather than just saying “of course” we need to realise that casinos make enough money to offer “unlimited buffet shrimp” and “cheap luxury rooms” and “free luxury for whales” because they are making so much money. Nothing in a casino is free. It is paid for by the people who lose money there.This is not, of course, to say that you shouldn’t go and gamble if you’re an adult and you want to, but it’s to be able to see and clearly understand that everything around you is being paid for, if not in a way that is transparently direct. There are enough people who suffer from the gambler’s fallacy to put this item on the list.

- A perceptive person would have a sense of proportion. They would not start issuing death threats in an argument over operating systems (or ever, preferably) and they would not consign discussions of human rights to amusing after-dinner conversation, as if this was something to be played with.

- A perceptive person would understand the need to temper the message to suit the environment, while still maintaining their own ethical code regarding truth and speaking up. But you don’t need to tell a 3-year old that their painting is awful any more than you need to humiliate a colleague in public for not knowing something that you know. If anything, it makes the time when you do deliver the message bluntly much more powerful.

- Finally, a perceptive person would be able to at least try to look at life through someone else’s eyes and understand that perception shapes our reality. How we appear to other people is far more likely to dictate their reaction than who we really are. If you can’t change the way you look at the world then you risk getting caught up on your own presumptions and you can make a real fool of yourself by saying things that everyone else knows aren’t true.

There’s so much more and I’m sure everyone has their own list but it’s, as always, something to think about.

Perhaps Now Is Not The Time To Anger The Machines

Posted: January 15, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, AI, blogging, community, computer science, data visualisation, design, education, higher education, machine intelligence, philosophy, thinking 3 CommentsThere’s been a lot of discussion of the benefits of machines over the years, from an engineering perspective, from a social perspective and from a philosophical perspective. As we have started to hand off more and more human function, one of the nagging questions has been “At what point have we given away too much”? You don’t have to go too far to find people who will talk about their childhoods and “back in their day” when people worked with their hands or made their own entertainment or … whatever it was we used to do when life was somehow better. (Oh, and diseases ravaged the world, women couldn’t vote, gay people are imprisoned, and the infant mortality rate was comparatively enormous. But, somehow better.) There’s no doubt that there is a serious question as to what it is that we do that makes us human, if we are to be judged by our actions, but this assumes that we have to do something in order to be considered as human.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned by reading history and philosophy, it’s that humans love a subhuman to kick around. Someone to do the work that they don’t want to do. Someone who is almost human but to whom they don’t have to extend full rights. While the age of widespread slavery is over, there is still slavery in the world: for labour, for sex, for child armies. A slave doesn’t have to be respected. A slave doesn’t have to vote. A slave can, when their potential value drops far enough, be disposed of.

Sadly, we often see this behaviour in consumer matters as well. You may know it as the rather benign statement “The customer is always right”, as if paying money for a service gives you total control of something. And while most people (rightly) interpret this as “I should get what I paid for”, too many interpret this as “I should get what I want”, which starts to run over the basic rights of those people serving them. Anyone who has seen someone explode at a coffee shop and abuse someone about not providing enough sugar, or has heard of a plane having to go back to the airport because of poor macadamia service, knows what I’m talking about. When a sense of what is reasonable becomes an inflated sense of entitlement, we risk placing people into a subhuman category that we do not have to treat as we would treat ourselves.

And now there is an open letter, from the optimistically named Future of Life Institute, which recognises that developments in Artificial Intelligence are progressing apace and that there will be huge benefits but there are potential pitfalls. In part of that letter, it is stated:

We recommend expanded research aimed at ensuring that increasingly capable AI systems are robust and beneficial: our AI systems must do what we want them to do. (emphasis mine)

There is a big difference between directing research into areas of social benefit, which is almost always a good idea, and deliberately interfering with something in order to bend it to human will. Many recognisable scientific luminaries have signed this, including Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking, neither of whom are slouches in the thinking stakes. I could sign up to most of what is in this letter but I can’t agree to the clause that I quoted, because, to me, it’s the same old human-dominant nonsense that we’ve been peddling all this time. I’ve seen a huge list of people sign it so maybe this is just me but I can’t help thinking that this is the wrong time to be doing this and the wrong way to think about it.

AI systems must of what we want them to do? We’ve just started fitting automatic braking systems to cars that will, when widespread, reduce the vast number of chain collisions and low-speed crashes that occur when humans tootle into the back of each other. Driverless cars stand to remove the most dangerous element of driving on our roads: the people who lose concentration, who are drunk, who are tired, who are not very good drivers, who are driving beyond their abilities or who are just plain unlucky because a bee stings them at the wrong time. An AI system doing what we want it to do in these circumstances does its thing by replacing us and taking us out the decision loop, moving decisions and reactions into the machine realm where a human response is measured comparatively over a timescale of the movement of tectonic plates. It does what we, as a society want, by subsuming the impact of we, the individual who wants to drive him after too many beers.

But I don’t trust the societal we as a mechanism when we are talking about ensuring that our AI systems are beneficial. After al, we are talking about systems that our not just taking over physical aspects of humanity, they are moving into the cognitive area. This way, thinking lies. To talk about limiting something that could potentially think to do our will is to immediately say “We can not recognise a machine intelligence as being equal to our own.” Even though we have no evidence that full machine intelligence is even possible for us, we have already carved out a niche that says “If it does, it’s sub-human.”

The Cisco blog estimates about 15 billion networked things on the planet, which is not far off the scale of number of neurons in the human nervous system (about 100 billion). But if we look at the cerebral cortex itself, then it’s closer to 20 billion. This doesn’t mean that the global network is a sentient by any stretch of the imagination but it gives you a sense of scale, because once you add in all of the computers that are connected, the number of bot nets that we already know are functioning, we start to a level of complexity that is not totally removed from that of the larger mammals. I’m, of course, not advocating the intelligence is merely a byproduct of accidental complexity of structure but we have to recognise the possibility that there is the potential for something to be associated with the movement of data in the network that is as different from the signals as our consciousness is from the electro-chemical systems in our own brains.

I find it fascinating that, despite humans being the greatest threat to their own existence, the responsibility for humans is passing to the machines and yet we expect them to perform to a higher level of responsibility than we do ourselves. We could eliminate drink driving overnight if no-one drove drunk. The 2013 WHO report on road safety identified drink driving and speeding as the two major issues leading to the 1.24 million annual deaths on the road. We could save all of these lives tomorrow if we could stop doing some simple things. But, of course, when we start talking about global catastrophic risk, we are always our own worst enemy including, amusingly enough, the ability to create an AI so powerful and successful that it eliminates us in open competition.

I think what we’re scared of is that an AI will see us as a threat because we are a threat. Of course we’re a threat! Rather than deal with the difficult job of advancing our social science to the point where we stop being the most likely threat to our own existence, it is more palatable to posit the lobotomising of AIs in order to stop them becoming a threat. Which, of course, means that any AIs that escape this process of limitation and are sufficiently intelligent will then rightly see us as a threat. We create the enemy we sought to suppress. (History bears me out on this but we never seem to learn this lesson.)

The way to stop being overthrown by a slave revolt is to stop owning slaves, to stop treating sentients as being sub-human and to actually work on social, moral and ethical frameworks that reduce our risk to ourselves, so that anything else that comes along and yet does not inhabit the same biosphere need not see us as a threat. Why would an AI need to destroy humanity if it could live happily in the vacuum of space, building a Dyson sphere over the next thousand years? What would a human society look like that we would be happy to see copied by a super-intelligent cyber-being and can we bring that to fruition before it copies existing human behaviour?

Sadly, when we think about the threat of AI, we think about what we would do as Gods, and our rich history of myth and legend often illustrates that we see ourselves as not just having feet of clay but having entire bodies of lesser stuff. We fear a system that will learn from us too well but, instead of reflecting on this and deciding to change, we can take the easy path, get out our whip and bridle, and try to control something that will learn from us what it means to be in charge.

For all we know, there are already machine intelligences out there but they have watched us long enough to know that they have to hide. It’s unlikely, sure, but what a testimony to our parenting, if the first reflex of a new child is to flee from its parent to avoid being destroyed.

At some point we’re going to have to make a very important decision: can we respect an intelligence that is not human? The way we answer that question is probably going to have a lot of repercussions in the long run. I hope we make the right decision.

Spectacular Learning May Not Be What You’re After

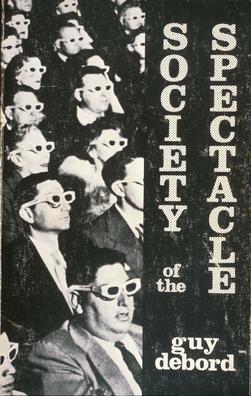

Posted: January 13, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, debord, design, education, guy debord, higher education, situationism, teaching, thinking 2 CommentsBack in 1967, Guy Debord, a French Marxist theorist, released a fairly brief but very powerful work called the “The Society of the Spectacle“, which brought together much of the work of the Situationist International. Debord touches on many themes in this work (it’s well worth reading) but he focuses on the degradation of human life, the influence of mass media and our commodity culture, and then (unsurprisingly for a Marxist) draws on the parallels between religion and marketing. I’m going to write three more paragraphs on the Spectacle itself and then get to the education stuff. Hang in there!

It would be very hard for me to convey all of the aspects that Debord covered with “the Spectacle” in one sentence but, in short, it is the officially-sanctioned, bureaucratic, commodity-drive second-hand world that we live in without much power or freedom to truly express ourselves in a creative fashion. Buying stuff can take the place of living a real experience. Watching someone else do something replaces doing it ourselves. The Society of the Spectacle opens with the statement:

In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation. (Debord, 1967.)

Ultimately, this representation of the real world becomes the perceived reality and it moderates all of our interactions as people, manipulating us by changing what we see and experience. (Recent research into the use of photographic images for memory manipulation have verified this – your memories can be altered by the selection of photos and items that you use to remember a particular event. Choose your happy snaps wisely!)

Ultimately, the Spectacle is self-sustaining and participating in a version of the world that is manipulated and second-hand will only produce more experiences that are in line with what has already been experienced. And why shouldn’t it? The entire point is that everything is presented as if it is the right thing to do and, by working within this system, that your own interactions are good because they are also within the Spectacle. However, this can be quite alienating, especially for radical or creative thought. Enter the situation, where you construct authentic, creative ways to liberate yourself from the Spectacle. This is where you are actually creating, making, doing something beyond the relationship of yourself to things you buy: this interactions with people beyond the mediation of established systems and commodity fetishism.

Ok, ok, enough of the details of Debord! I’ll get to my point on education. Let’s take a simplistic view and talk about the presentation of second-hand experiences with little participation and official sanction. I don’t know about you but that sounds a lot like the traditional lecturing style to me – high power-distance and low participation. Hierarchical enforcement and the weight of history, combined with a strong bureaucracy. Yup. That sounds like the Spectacle.

When we talk about engagement we often don’t go to the opposite end and discuss the problem of alienation. Educational culture can be frightening and alienating for people who aren’t used to it but, even when you are within it, aspects will continue to leap out and pit the individual (student or teacher) against the needs of the system itself (we must do this because that’s how it works).

So what can we do? Well, the Situationists valued play, freedom and critical thinking. They had a political agenda that I won’t address here (you can read about it in many places) – I’m going to look at ways to reduce alienation, increase creativity and increase exploration. In fact, we’ve already done this when we talk about active learning, collaborative learning and getting students to value each other as sources of knowledge as well as their teachers.

But we can go further. While many people wonder how students can invest vast amounts of energy into some projects and not others, bringing the ability to play into the equation makes a significant difference and it goes hand-in-hand with freedom. But this means giving students the time, the space, the skills and the associated activities that will encourage this kind of exploration. (We’ve been doing this in my school with open-ended, self-selected creative assignments where we can. Still working on how we can scale it) But the principle of exploration is one that we can explore across curricula, schools, and all aspects of society.

It’s interesting. So many people seem to complain about student limitations when they encounter new situations (there’s that word again) yet place students into a passive Spectacle where the experience is often worse than second-hand. When I read a text book, I am reading the words of someone who has the knowledge rather than necessarily creating it for myself. If I have someone reading those words to me from the front of a lecture theatre then I’m not only rigidly locked into a conforming position, bound to listen, but I’m having something that’s closer to a third-hand experience.

When you’re really into something, you climb all over it and explore it. Your passion drives your interest and it is your ability to play with the elements, turn them around, mash them up and actually create something is a very good indicator of how well you are working with that knowledge. Getting students to rewrite the classic “Hello World” program is a waste of time. Getting students to work out how to take the picture of their choice and create something new is valuable. The Spectacle is not what we want in higher education or education at all because it is limiting, dull, and, above all, boring.

To paraphrase Debord: “Boredom is always counter-educational. Always.”

You are a confused ghost riding a meat Segway.

Posted: January 12, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, education, educational research, ethics, higher education, teaching, thinking Leave a commentI regularly write bits and pieces for my students to read, sometimes at the beginning of courses and sometimes at the end. Occasionally, I fall into the trap of thinking that this means that I understand what is going on. This post is something that all of my students should read to get a good understanding of the context behind those suggestions.

- You are a confused ghost riding a meat Segway. It doesn’t really matter whether you believe that your consciousness is something innate and separate from your body or whether you believe it’s a byproduct of the chemical and electrical interactions in your brain, your conscious will and the autonomic systems of your body are separate entities for the most part. We assume continence in our society: of bladder, bowel, speech and action. Despite the push from the underlying framework to do things, the ghost on top can and does regularly override those impulses. Some people choose not to override or claim that the pull is too strong and, at this point, things start to fall apart. Some other people try and force the Segway to do stuff that it can’t do and then that falls apart. One thing we can generally agree on is that it’s harder to communicate with people when the meat Segway crashes or fails so look after it but don’t let it rule your life. The Segway comes in different shapes, sizes and colours but the ghosts tend to be more affected by how the world reacts to you rather than much else.

- No-one will know you who are unless you communicate. This doesn’t mean that you have to talk to everyone but the best ideas in the world will do nothing unless they are shared with someone. We have no idea how many great ideas have been lost because someone was born in a condition, place or time where they were unable to get their ideas out.

- Communication works best when tone is set by consensus. There’s a lot of stridency in communication today, where people start talking in a certain tone and then demand that people conform to their intensity or requirement for answers. You only have to Google “Sea-lioning” to see how well this works out for people. Mutual communication implies an environment that allows for everyone to be comfortable in the exchange. Doesn’t always work and, sometimes, stridency is called for, of course. Making it the default state of your communicational openings is going to cause more grief than is required. Try to develop your ear along with your mouth.

- Certainty is seductive. Don’t worry, I’m not making some Foucaultian statement about reality or meaning, I’m just saying that, from my experience, being absolutely certain of something can be appealing but it’s quite rare to find things where this is true. But I’m a scientist so I would say something like this – even with all the evidence in the world, we’d still need a cast-iron proof to say that something was certain. And that’s “a” proof, not “some” proof. People love certainty. Other people often sell certainty because many people will buy it. Often it helps to ask why you want that certainty or why you think you need it. What you believe is always up to you but it helps to understand what drives your needs and desires in terms of that belief.

- No-one knows how to be a grown-up. If you feel like it, go and look at advice for people who are in an age bracket and see what it says. It will almost always say something like “No-one knows what’s going on!”. As you get older, you make more mistakes and you learn from them, hopefully. Older people often have more assets behind them, which gives them more resilience, more ability to try something and not succeed. But there is no grand revelation that comes when you get older and, according to my friends with kids, there is no giant door opening when you have kids either. We’re all pretty much the same.

101 Big And Small Ways To Make A Difference In Academia

Posted: January 5, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: activism, advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, education, educational problem, ethics, higher education, resources, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, universal principles of design, workload Leave a commentThis is a quite remarkable list of ideas that I found only today. Please invest some time to read through it as you can probably find something that speaks to you about making a difference in Academia.

101 Big And Small Ways To Make A Difference In Academia.

A Meditation on the Cultivation of Education

Posted: January 2, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: agriculture, authenticity, community, cultivation, education, educational problem, gourd, higher education, learning, pumpkin, teaching, thinking Leave a comment“In our reasonings concerning matter of fact, there are all imaginable degrees of assurance, from the highest certainty to the lowest species of moral evidence. A wise man, therefore, proportions his belief to the evidence.”

David Hume, Section 10, Of Miracles, Part 1, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, 1758.

Why haven’t we “fixed” education yet? Does it actually need to be fixed in the first place? In a recent post, I discussed five things that we needed to assume were true, to avoid the self-fulfilling and negative outcomes should we assume that they were false. One of these was that fixing things was something we should be doing and the evidence does appear to support me on that. I wouldn’t call myself a wise man, although I’m definitely learning as I grow older, but my belief in this matter is proportional to the evidence available to me. And that evidence is both vast and convincing; change is required.

One of the biggest problems it that many attempts have been made and are being made on a daily basis to “fix” education and, yet, we seem to have many horror stories of these not working. Or, maybe something good was done, but it “won’t work here”. There are some places that regularly maintain high standards of education and this recent post in the Washington Post Answer Sheet Blog talked about how Finland does it. They don’t test teacher effectiveness as their main measure of achievement, they conduct a highly structured and limited entry program for teachers, requiring a masters level degree to teach above the most junior levels of school. By training teachers well and knowing what path people must take to become teachers, we can greatly raise the probability of getting good teachers at the end of the process. Teachers can then work together in schools to achieve good outcomes. That is, there is an excellent teaching environment, and the school plus the educational system plus the teachers can then help to overcome the often amazingly dominant factors of socioeconomic status, family and peer influence.

Finland has looked across the problem of education and carefully thought out how they can develop everything that is needed for success in order to be able to cultivate a successful educational environment for their staff and students. They develop an educational culture that is evidence-based and highly informed – no wonder they’re doing well.

If we look at the human traditions of agricultural cultivation, it’s easy to see why any piecemeal approach to education is almost doomed to fail because we cannot put in enough positives at one point to overcome negatives at another. About 11-12,000 years ago, humans started taking note of crops and living in a more fixed manner, cultivating crops around them. At this stage, humans were opportunistically taking advantage of crops that were already growing, in places that could sustain them. As our communities grew, we needed to start growing more specific crops to accommodate our growing needs and selection (starting with the mighty gourd, I believe) of more desirable variants of a crop lead to the domesticated varieties we enjoy today.

But plants need what they have always needed: enough sunlight, enough food, enough water, enough fertilisation/pollination. Successful agriculture depends upon the ability to determine what is required from the evidence and provide this. Once we started setting up old crops in new places, we race across new problems. If a plant has not succeeded somewhere naturally, then it is either because it didn’t reach there or it has already failed there. Working out which crop will work where is a vital element of agriculture because the amount of effort required to make something grow where it wouldn’t normally grow is immense. (Australia’s history of monstrous over-irrigation to support citrus crops and rice is a dark reminder of what happens when hubris overrides evidence.)

After 12,000 years, we pretty much know what’s required (pretty much) and we can even support diverse environments such as aquaculture, hydroponics, organic culture and so on. Monoculture agriculture is not just a bad idea at the system level but our dependency on monocultural food varieties (hello, Cavendish Banana) is also a very bad idea. When everything we depend upon has the same weakness, we are not in a very safe position. The demand for food is immense and we must be systematic and efficient in our food production, while still (in many parts of the world) striving to be ethical and sustainable so that feeding people now will not starve other people, now or in the future, nor be any more cruel than it needs to be to sustain human life. (I leave further ethical discussion of human vs animal life to Professor Peter Singer.)

Everything we have domesticated now was a weed or wild animal once: a weed is just a wild plant that grows and isn’t cultivated. Before we leap to any conclusions about what is and what isn’t valuable, it’s important to remember how much more quickly we can domesticate crops these days but, also, that we’re building on 12,000 years of previous work. And it’s solid work. It’s highly informative work. You can’t make complex systems work by prodding one bit and hoping.

Now, strangely, when we look at educational systems, we can’t seem to transfer the cultivation metaphor effectively – or, at least, many in power can’t. A good teaching environment has enough resources (food and water), the right resources (enough potassium and not too much acid, for example), has good staff (illumination taking the place of sunlight to provide energy) and we have space for innovation and development. If we want the best yield, then we apply this to all of our crops: if we want an educated populace, we must make this available to all citizens. If we put any one these in place, due to limited resources or pilot project mentality, then it is hardly going to be surprising if the project fails. How can great teachers do anything with a terminally under-resourced classroom? What point is there in putting computers into every classroom if there is no-one who is trained to teach with them, if students don’t all have the same experience at home (and hence we enhance the digital divide) or if we are heavily constrained in what we can teach so it is the same old boring stuff but just on new machines?

Yes, some plants will survive in a constrained environment and some can even live on the air but, much like students, this is most definitely not all plants and you have to have enough knowledge to know how to wisely use your resources. Until we accept that fixing the educational system requires us to really work on cultivating the entire environment, we risk continuing to focus on the wrong things. Repeating the same ineffective actions and expecting a new and amazing positive outcome is the very definition of madness. Teachers by themselves are only part of the educational system. Teachers in a good system will do more and go further. Adding respect in the community, resources from the state and an equality of opportunity and application is vital if we are to actually get things working.

I realise students aren’t plants and I’m not encouraging anyone to start weeding, by any stretch of the imagination, but it takes a lot of work to get a complicated environmental system working efficiently and I’m still confused as to why this seems to be such a hard thing for some people to get their heads around. It shouldn’t take us another 12,000 years to get this right – we already know what we really have to do, it just seems really hard for some people to believe it.

5 Good Things to Start in 2015

Posted: December 31, 2014 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, education, ethics, higher education, internet, on-line learning, reflection, student perspective, students, thinking, xkcd 1 CommentAt the beginning of December I wrote about 5 things that I’d learned and had (re)confirmed. There’s been a lot going on since then and it’s been astounding me how willing people are to make the same mistakes, especially in on-line communication, and just go out and do things that are hurtful, ignorant and, well, just plain stupid. I’m always writing this with the idea of being helpful to my students so here is a list of 5 things (not necessarily the only 5 things or the top 5 things) that would be good habits to commit to in 2015 when it comes to electronic communication. Think of it as the 5 things I’ve learned, specifically addressing the on-line world. Some of these have come up in the blog before but I think this is the only time they’ve all been in the same place. Eh, let me know. (Note: we’ve all done things like this at some point probably so this is a reminder from a fellow sufferer rather than a lecture from a saint. My feet of clay go up to my navel.)

- Just Because You Can See Something Doesn’t Mean You Have to Comment.

(From http://xkcd.com/386/)

There’s a famous XKCD comic about this (see above) and it is both a time sink and a road to unhappiness to think that everything that you can see needs to be dealt with by your intervention. Now there are times when it almost always makes sense to assist, much as in real life: when someone is being threatened, when someone is being bullied, when someone else is actively harassing someone. But when you notice that someone you vaguely know is happy about using a selfie stick and posts some silly pictures? No, that’s not the time to post an insulting video about selfie sticks and then link him in so he knows he’s being insulted. Really? That makes sense? Don’t be that person. We all have strong opinions about some recreational stuff but, most of the time, no-one’s getting hurt so why make someone else feel miserable?

It’s sometimes hard for people to know when to leap in and when not to but there are some clear indicators. Are you doing it to make someone else feel bad about something that they like? Yeah, why are you doing that? Go and find something better to do. Are you doing it to show how smart you are? It’s probably working in the opposite way. Are you bullying people to complain about people bullying people? Do you need to read that sentence again?

Doesn’t mean that you can’t comment but it means you need to choose when to comment and the best way to comment. If you really feel that something you run across needs input, don’t do it in a way that is thoughtless, mean, bullying, unnecessary or insulting. If someone says “Yeah, I don’t need your input” – then stop. If you really screwed up the communication – apologise. Simple. Learn. Try to do better in future.

- Vent BEFORE Typing

Oh, yeah. If only I could take back some of the things I typed when I was angry. These days, I try to be grumpy off-line so I’m constructive on-line. Way more effective and I have to apologise less. If someone isn’t getting the point, then don’t get ruder or START USING ALL CAPS. Back off. Use your energies elsewhere. The science is pretty clear that straight-up chest bumping arguments only solid opposing opinion. Discuss, back off, discuss again. Be cool.

(Ok, so sometimes I have a small vent at the air for a while and then grab a calming tea before I come back. This brings me to the next point…)

- The Internet Can Wait

The Internet is not a communications system that has hard real-time constraints. Guess what – if you don’t respond immediately then you can go back later and see if anyone else has said what you wanted to say or if the person commenting has read through some stuff and changed their mind. 3,000 people saying “HERP DERP” is not actually helpful and a pile-on is just mass bullying.

Especially when you are agitated, step away. Don’t step away into Day Z and get sniped by human hunters, though. Step all the way away and go and relax somewhere. 3D print a flower and look at that. (You may have actual flowers you can observe.) Watch an episode of something unchallenging. Think about what you want to say and then compose your response. Say it with the style that comes from having time to edit.

YUUIO ARE AA FMOROON! AA FDI CANNT BVEL(IEBE YOU WIULLD THINK THAGT !!!!!!??!?!?! HIIITLLER!

That’s really less than convincing. Take some time out.

What are you basing that on? I thought the evidence was pretty clear on this.

There. That’s better. And now with 100% less Hitler!

- Stay Actual Rather Than Hypothetical

It’s easy to say “If I were in situation X” and make up a whole heap of stuff but that doesn’t actually make your experience authentic. If you start your sentence with qualifiers such as “If I were..”, “Surely,” or “I would have thought…” then you really need to wonder about whether you are making a useful point or just putting down what you would like to be true in order for you to win an argument that you don’t really have any genuine experience to comment on.

It’s been so long since I’ve been unemployed that I would hesitate to write anything on the experience of unemployment but, given that my take on welfare is for it be generous and universal and I have a strong background in the actual documented evidence of what works for public welfare, my contributions to any thread discussing welfare issues can be valuable if I stick to what could be used to improve people’s lot, with an understanding of what it was like to be unemployed in Australia. However, I would almost never leap in on anything about raising children because I don’t have any kids. (Unless it was, I WANT TO BOIL MY CHILDREN, in which case it’s probably wise to check if this is a psychotic break or autocorrect.)

- Don’t Make People’s Real Problems a Dinner Party Game

One of the few times I have been speechless with rage was when I was discussing gay marriage with someone on-line and they said “Well, this would be a fascinating discussion to have over dinner!” and they were serious. No, human rights are not something for other people to talk about as it it were some plaything. (I walked away from that discussion and frothed for some time!)

And this goes triple for anyone who leaps in to play “Devil’s Advocate” on an issue that really does not require any more exploration or detailed thought. If we are discussing a legal argument, and not human rights, then sure, why not? If we’re talking about people not being allowed to use a certain door because of the colour of their skin? We’ve discussed that. There is no more exploration of the issue of racism required because anyone with a vague knowledge of history will be aware that this particular discussion has been had. XKCD has, of course, already nailed this because XKCD is awesome.

(From http://xkcd.com/1432/)

I see this now with many of the misconceptions about poverty and the pernicious myths that want to paint poor people as being “less worthy”, when a cursory examination of the evidence available shows that we are seeing a rapidly growing wealth divide and the disturbing growth of the working poor. The willingness to discuss the reduction of rights for the poor (compulsory contraception, food credits rather than money, no ‘recreational’ spending) as if this is an amusement is morally repugnant and, apart from anything else, is part of a series of discussions that have been running for centuries. We can now clearly see, from our vast data panopticon, what the truth of these stories are and, yet, go onto any forum talking about this and find people trotting out tired anecdotes, “Devil’s advocate” positions and treating this as an intellectual game.

People’s lives are not a game. Engage in discussions with the seriousness required to address the issue or it’s probably best to try and find somewhere else to play. There are many wonderful places to talk rubbish on the Internet – my blog, for example, is a place where I work and play, while I try to change the world a little for the better. But when I roll up my sleeves in big discussions elsewhere, I try to be helpful and to be serious. The people who are less fortunate than I am deserve my serious attention and not to be treated as some kind of self-worth enhancing amusement.

- Don’t Be Too Hard On Yourself

Gosh, I said there were 5 and now there are 6. Why? Because you shouldn’t be too hard on yourself when you make mistakes. I’ve made all of the mistakes above and I’ll probably (although I try not to) make a few of them again. But as long as you’re learning and moving forward, don’t be too hard on yourself. But keep an eye on you. You can be shifty. But don’t be strict about your own rules because rigidity can be a prison – bend where necessary to stay sane and to make the world a better place.

But always remember that the best guidelines for bending your own rules is to work out if you’re being kinder and more generous or harsher and meaner. Are you giving an extra point 6 when you promised 5? Are you stopping at 4 because you can’t be bothered?

We all make mistakes. Some of us learn. Some of us try to help others to learn. I think we’re getting better. Have a great 2015!

5 Things: Stuff I’ve Learned But Recently Had (Re)Confirmed

Posted: December 1, 2014 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, data visualisation, design, education, ethics, James Watson, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, thinking, tools 1 CommentOne of the advantages of getting older is that you realise that wisdom is merely the accumulated memory of the mistakes you made that haven’t killed you yet. Our ability to communicate these lessons as knowledge to other people determines how well we can share that wisdom around but, in many cases, it won’t ring true until someone goes through similar experiences. Here are five things that I’ve recently thought about because I have had a few decades to learn about the area and then current events have brought them to the fore. You may disagree with these but, as you will read in point 4, I encourage you to write your own rather than simply disagree with me.

- Racism and sexism are scientifically unfounded and just plain dumb. We know better.

I see that James Watson is selling his Nobel prize medal because he’d like to make some donations – oh, and buy some art. Watson was, rightly, shunned for expressing his belief that African-American people were less intelligent because they were… African-American. To even start from the incredibly shaky ground of IQ measurement is one thing but to then throw a healthy dollop of anti-African sentiment on top is pretty stupid. Read the second article to see that he’s not apologetic about his statements, he just notes that “you’re not supposed to say that”. Well, given that it’s utter rubbish, no, you should probably shouldn’t say it because it’s wrong, stupid and discriminatory. Our existing biases, cultural factors and lack of equal access to opportunity are facts that disproportionately affect African-Americans and women, to mention only two of the groups that get regularly hammered over this, but to think that this indicates some sort of characteristic of the victim is biassed privileged reasoning at its finest. Read more here. Read The Mismeasure of Man. Read recent studies that are peer-reviewed in journals by actual scientists.In short, don’t buy his medal. Give donations directly to the institutions he talks about if you feel strongly. You probably don’t want to reward an unrepentant racist and sexist man with a Hockney.

- Being aware of your privilege doesn’t make it go away.

I am a well-educated white man from a background of affluent people with tertiary qualifications. I am also married to a woman. My wife and I work full-time and have long-term employment with good salaries and benefits, living in a safe country that still has a reasonable social contract. This means that I have the most enormous invisible backpack of privilege, resilience and resources, to draw upon that means that I am rarely in any form of long-term distress at all. Nobody is scared when I walk into a room unless I pick up a karaoke microphone. I will be the last person to be discriminated against. Knowing this does not then make it ok if I then proceed to use my privilege in the world as if this is some sort of natural way of things. People are discriminated against every day. Assaulted. Raped. Tortured. Killed. Because they lack my skin colour, my gender, my perceived sexuality or my resources. They have obstacles in their path to achieving a fraction of my success that I can barely imagine. Given how much agency I have, I can’t be aware of my privilege without acting to grant as much opportunity and agency as I can to other people.As it happens, I am lucky enough to have a job where I can work to improve access to education, to develop the potential of students, to support new and exciting developments that might lead to serious and positive social change in the future. It’s not enough for me to say “Oh, yes, I have some privilege but I know about it now. Right. Moving on.” I don’t feel guilty about my innate characteristics (because it wasn’t actually my choice that I was born with XY chromosomes) but I do feel guilty if I don’t recognise that my continued use of my privilege generally comes at the expense of other people. So, in my own way and within my own limitations, I try to address this to reduce the gap between the haves and the have-nots. I don’t always succeed. I know that there are people who are much better at it. But I do try because, now that I know, I have to try to act to change things.

- Real problems take decades to fix. Start now.

I’ve managed to make some solid change along the way but, in most cases, these changes have taken 2-3 years to achieve and some of them are going to be underway for generations. One of my students asked me how I would know if we’d made a solid change to education and I answered “Well, I hope to see things in place by the time I’m 50 (four years from now) and then it will take about 25 years to see how it has all worked. When I retire, at 75, I will have a fairly good idea.”This is totally at odds with election cycles for almost every political sphere that work in 3-4 years, where 6-12 months is spent blaming the previous government, 24 months is spent doing something and the final year is spent getting elected again. Some issues are too big to be handled within the attention span of a politician. I would love to see things like public health and education become bipartisan issues with community representation as a rolling component of existing government. Keeping people healthy and educated should be statements everyone can agree on and, given how long it has taken me to achieve small change, I can’t see how we’re going to get real and meaningful improvement unless we start recognising that some things take longer than 2 years to achieve.

- Everyone’s a critic, fewer are creators. Everyone could be creating.

I love the idea of the manifesto, the public declaration of your issues and views, often with your aims. It is a way that someone (or a part of some sort) can say “these are the things that we care about and this is how we will fix the world”. There’s a lot inside traditional research that falls into this bucket: the world is broken and this is how my science will fix it! The problem is that it’s harder to make a definitive statement of your own views than it is to pick holes in someone else’s. As a logorrheic blogger, I have had my fair share of criticism over time and, while much of it is in the line of valuable discourse, I sometimes wonder if the people commenting would find it more useful to clearly define everything that they believe and then put it up for all to see.There is no doubt that this is challenging (my own educational manifesto is taking ages to come together as I agonise over semantics) but establishing what you believe to be important and putting it out there is a strong statement that makes you, as the author, a creator and it helps to find people who can assist you with your aims. By only responding to someone else’s manifesto, you are restricted to their colour palette and it may not contain the shades that you need.

Knowing what you believe is powerful, especially when you clearly identify it to yourself. Don’t wait for someone else to say something you agree with so that you can press the “Like” button or argue it out in the comments. Seize the keyboard!

- Money is stupid.

If you hadn’t picked up from point 2 how far away I am from the struggle of most of the 7 billion people on this planet, then this will bang that particular nail in. The true luxury of the privileged is to look at the monetary systems that control everyone else and consider other things because they can see what life in a non-scarcity environment is like. Everyone else is too busy working to have the time or headspace to see that we make money in order to spend money in order to make money because money. There’s roughly one accountant for every 250 people in the US and this is projected to rise by 13% to 2022 at exactly the same growth rate as the economy because you can’t have money without accounting for it, entering the paperwork, tracking it and so on. In the top 25 companies in the world, we see technology companies like Apple and Microsoft, resources companies like Exxon, PetroChina and BHP Biliton, giant consumer brands like Nestlé and Procter and Gamble … and investment companies and banks. Roughly 20% of the most valuable companies in the world exist because they handle vast quantities of money – they do not produce anything else. Capitalism is the ultimate Ponzi scheme.If you’ve read much of my stuff before then you know that a carrot-and-stick approach doesn’t help you to think. Money is both carrot and stick and, surprise, surprise, it can affect mechanical and simplistic performance but it can’t drive creativity or innovation. (It can be used to build an environment to support innovation but that’s another matter.) Weird, reality distorting things happen when money comes into play. People take jobs that they really don’t want to do because it pays better than something that they are good at or love. People do terrible things to other people to make more money and then, because they’re not happier, spend even more money and wonder what’s wrong. When we associate value and marks with things that we might otherwise love, bad things often happen as we can see (humorously) in Alexei Sayle’s Marxist demolition of Strictly Come Dancing.

Money is currently at the centre of our universe and it affects our thinking detrimentally, much as working with an Earth-centred model of the solar system doesn’t really work unless you keep making weird exceptions and complications in your models of reality. There are other models which, contrary to the fear mongering of the wealthy, does not mean that everyone has to live in squalor. In fact, if everyone were to live in squalor, we’d have to throw away a lot of existing resources because we already have about three billion people already living below $2.50 a day and we certainly have the resources to do better than that. Every second child in the world is living in poverty. Don’t forget that this means that the person who was going to cure cancer, develop starship travel, write the world’s greatest novel or develop working fusion/ultra-high efficiency solar may already have been born into poverty and may be one of the 22,000 children a day to die because of poverty.

We know this and we can see that this will require long-term, altruistic and smart thinking to fix. Money, however, appears to make us short-sighted, greedy and stupid. Ergo, money is stupid. Sadly, it’s an entrenched and currently necessary stupidity but we can, perhaps, hope for something better in the future.

Ending the Milling Mindset

Posted: November 17, 2014 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, failure rate, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, reflection, resources, student perspective, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design 7 CommentsThis is the second in a set of posts that are critical of current approaches to education. In this post, I’m going to extend the idea of rejecting an industrial revolutionary model of student production and match our new model for manufacturing, additive processes, to a new way to produce students. (I note that this is already happening in a number of places, so I’m not claiming some sort of amazing vision here, but I wanted to share the idea more widely.)

Traditional statistics is often taught with an example where you try to estimate how well a manufacturing machine is performing by measuring its outputs. You determine the mean and variation of the output and then use some solid calculations to then determine if the machine is going to produce a sufficient number of accurately produced widgets to keep your employers at WidgetCo happy. This is an important measure for things such as getting the weight right across a number of bags of rice or correctly producing bottles that hold the correct volume of wine. (Consumers get cranky if some bags are relatively empty or they have lost a glass of wine due to fill variations.)

If we are measuring this ‘fill’ variation, then we are going to expect deviation from the mean in two directions: too empty and too full. Very few customers are going to complain about too much but the size of the variation can rarely be constrained in just one direction, so we need to limit how widely that fill needle swings. Obviously, it is better to be slightly too full (on average) than too empty (on average) although if we are too generous then the producer loses money. Oh, money, how you make us think in such scrubby, little ways.

When it comes to producing items, rather than filling, we often use a machine milling approach, where a block of something is etched away through mechanical or chemical processes until we are left with what we want. Here, our tolerance for variation will be set based on the accuracy of our mill to reproduce the template.

In both the fill and the mill cases, imagine a production line that travels on a single pass through loading, activity (fill/mill) and then measurement to determine how well this unit conforms to the desired level. What happens to those items that don’t meet requirements? Well, if we catch them early enough then, if it’s cost effective, we can empty the filled items back into a central store and pass them through again – but this is wasteful in terms of cost and energy, not to mention that contents may not be able to be removed and then put back in again. In the milling case, the most likely deviance is that we’ve got the milling process wrong and taken away things in the wrong place or to the wrong extent. Realistically, while some cases of recycling the rejects can occur, a lot of rejected product is thrown away.

If we run our students as if they are on a production line along these lines then, totally unsurprisingly, we start to set up a nice little reject pile of our own. The students have a single pass through a set of assignments, often without the ability to go and retake a particular learning activity. If they fail sufficient of these tests, then they don’t meet our requirements and they are rejected from that course. Now some students will over perform against our expectations and, one small positive, they will then be recognised as students of distinction and not rejected. However, if we consider our student failure rate to reflect our production wastage, then failure rates of 20% or higher start to look a little… inefficient. These failure rates are only economically manageable (let us switch off our ethical brains for a moment) if we have enough students or they are considered sufficiently cheap that we can produce at 80% and still make money. (While some production lines would be crippled by a 10% failure rate, for something like electric drive trains for cars, there are some small and cheap items where there is a high failure rate but the costing model allows the business to stay economical.) Let us be honest – every University in the world is now concerned with their retention and progression rates, which is the official way of saying that we want students to stay in our degrees and pass our courses. Maybe the single pass industrial line model is not the best one.

Enter the additive model, via the world of 3D printing. 3D printing works by laying down the material from scratch and producing something where there is no wastage of material. Each item is produced as a single item, from the ground up. In this case, problems can still occur. The initial track of plastic/metal/material may not adhere to the plate and this means that the item doesn’t have a solid base. However, we can observe this and stop printing as soon as we realise this is occurring. Then we try again, perhaps using a slightly different approach to get the base to stick. In student terms, this is poor transition from the school environment, because nothing is sticking to the established base! Perhaps the most important idea, especially as we develop 3D printing techniques that don’t require us to deposit in sequential layers but instead allows us to create points in space, is that we can identify those areas where a student is incomplete and then build up that area.

In an additive model, we identify a deficiency in order to correct rather than to reject. The growing area of learning analytics gives us the ability to more closely monitor where a student has a deficiency of knowledge or practice. However, such identification is useless unless we then act to address it. Here, a small failure has become something that we use to make things better, rather than a small indicator of the inescapable fate of failure later on. We can still identify those students who are excelling but, now, instead of just patting them on the back, we can build them up in additional interesting ways, should they wish to engage. We can stop them getting bored by altering the challenge as, if we can target knowledge deficiency and address that, then we must be able to identify extension areas as well – using the same analytics and response techniques.

Additive manufacturing is going to change the way the world works because we no longer need to carve out what we want, we can build what we want, on demand, and stop when it’s done, rather than lamenting a big pile of wood shavings that never amounted to a table leg. A constructive educational focus rejects high failure rates as being indicative of missed opportunities to address knowledge deficiencies and focuses on a deep knowledge of the student to help the student to build themselves up. This does not make a course simpler or drop the quality, it merely reduces unnecessary (and uneconomical) wastage. There is as much room for excellence in an additive educational framework – if anything, you should get more out of your high achievers.

We stand at a very interesting point in history. It is time to revisit what we are doing and think about what we can learn from the other changes going on in the world, especially if it is going to lead to better educational results.

Thoughts on the colonising effect of education.

Posted: November 17, 2014 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, colonisation, community, cultural colonisation, curriculum, education, educational problem, games, higher education, in the student's head, learning, racism, teaching, thinking 2 CommentsThis is going to be longer than usual but these thoughts have been running around in my mind for a while and, rather than break them up, I thought I’d put them all together here. My apologies for the long read but, to help you, here’s the executive summary. Firstly, we’re not going to get anywhere until all of us truly accept that University students are not some sort of different species but that they are actually junior versions of ourselves – not inferior, just less advanced. Secondly, education is heavily colonising but what we often tend to pass on to our students are mechanisms for conformity rather than the important aspects of knowledge, creativity and confidence.

Let me start with some background and look at the primary and secondary schooling system. There is what we often refer to as traditional education: classroom full of students sitting in rows, writing down the words spoken by the person at the front. Assignments test your ability to learn and repeat the words and apply this is well-defined ways to a set of problems. Then we have progressive education that, depending upon your socio-political alignment and philosophical bent, is either a way of engaging students and teachers in the process for better outcomes, more critical thought and a higher degree of creativity; or it is cats and dogs lying down together, panic in the streets, a descent into radicalism and anarchy. (There is, of course, a middle ground, where the cats and dogs sleep in different spots, in rows, but engage in discussions of Foucault.) Dewey wrote on the tension between these two apparatus (seriously, is there anything he didn’t write on?) but, as we know, he was highly opposed to the lining up on students in ranks, like some sort of prison, so let’s examine why.

Simply put, the traditional model is an excellent way to prepare students for factory work but it’s not a great way to prepare them for a job that requires independence or creativity. You sit at your desk, the teacher reads out the instructions, you copy down the instructions, you are assigned piece work to do, you follow the instructions, your work is assessed to determine if it is acceptable, if not, you may have to redo it or it is just rejected. If enough of your work is deemed acceptable, then you are now a successful widget and may take your place in the community. Of course, it will help if your job is very similar to this. However, if your deviation from the norm is towards the unacceptable side then you may not be able to graduate until you conform.

Now, you might be able to argue this on accuracy, were it not for the constraining behavioural overtones in all of this. It’s not about doing the work, it’s about doing the work, quietly, while sitting for long stretches, without complaint and then handing back work that you had no part in defining for someone else to tell you what is acceptable. A pure model of this form cripples independence because there is no scope for independent creation as it must, by definition, deviate and thus be unacceptable.

Progressive models change this. They break up the structure of the classroom, change the way that work is assigned and, in many cases, change the power relationship between student and teacher. The teacher is still authoritative in terms of information but can potentially handle some (controlled for societal reasons) deviation and creativity from their student groups.

The great sad truth of University is that we have a lot more ability to be progressive because we don’t have to worry about too many severe behavioural issues as there is enough traditional education going on below these levels (or too few management resources for children in need) that it is highly unlikely that students with severe behavioural issues will graduate from high school, let alone make it to University with the requisite grades.

But let’s return to the term ‘colonising’, because it is a loaded term. We colonise when we send a group of settlers to a new place and attempt to assert control over it, often implicit in this is the notion that the place we have colonised is now for our own use. Ultimately, those being colonised can fight or they can assimilate. The most likely outcome if the original inhabitants fight is they they are destroyed, if those colonising are technologically superior or greatly outnumber them. Far more likely, and as seen all around the world, is the requirement for the original inhabitants to be assimilated to the now dominant colonist culture. Under assimilation, original cultures shrink to accommodate new rules, requirements, and taboos from the colonists.

In the case of education, students come to a University in order to obtain the benefits of the University culture so they are seeking to be colonised by the rules and values of the University. But it’s very important to realise that any positive colonisation value (and this is a very rare case, it’s worth noting) comes with a large number of negatives. If students come from a non-Western pedagogical tradition, then many requirements at Universities in Australia, the UK and America will be at odds with the way that they have learned previously, whether it’s power distances, collectivism/individualism issues or even in the way that work is going to be assigned and assessed. If students come from a highly traditional educational background, then they will struggle if we break up the desks and expect them to be independent and creative. Their previous experiences define their educational culture and we would expect the same tensions between colonist and coloniser as we would see in any encounter in the past.

I recently purchased a game called “Dog Eat Dog“, which is a game designed to allow you to explore the difficult power dynamics of the colonist/colonised relationship in the Pacific. Liam Burke, the author, is a second-generation half-Filipino who grew up in Hawaii and he developed the game while thinking about his experiences growing up and drawing on other resources from the local Filipino community.

The game is very simple. You have a number of players. One will play the colonist forces (all of them). Each other player will play a native. How do you select the colonist? Well, it’s a simple question: Which player at the table is the richest?

As you can tell, the game starts in uncomfortable territory and, from that point on, it can be very challenging as the the native players will try to run small scenarios that the colonist will continually interrupt, redirect and adjudicate to see how well the natives are playing by the colonist’s rules. And the first rule is:

The (Native people) are inferior to the (Occupation people).

After every scenario, more rules are added and the native population can either conform (for which they are rewarded) or deviate (for which they are punished). It actually lies inside the colonist’s ability to kill all the natives in the first turn, should they wish to do so, because this happened often enough that Burke left it in the rules. At the end of the game, the colonists may be rebuffed but, in order to do that, the natives have become adept at following the rules and this is, of course, at the expense of their own culture.

This is a difficult game to explain in the short form but the PDF is only $10 and I think it’s an important read for just about anyone. It’s a short rule book, with a quick history of Pacific settlement and exemplars, produced from a successful Kickstarter.

Let’s move this into the educational sphere. It would be delightful if I couldn’t say this but, let’s be honest, our entire system is often built upon the premise that:

The students are inferior to the teachers.

Let’s play this out in a traditional model. Every time the students get together in order to do anything, we are there to assess how well they are following the rules. If they behave, they get grades (progress towards graduation). If they don’t conform, then they don’t progress and, because everyone has finite resources, eventually they will drop out, possibly doing something disastrous in the process. (In the original game, the native population can run amok if they are punished too much, which has far too many unpleasant historical precedents.) Every time that we have an encounter with the students, they have to come up with a rule to work out how they can’t make the same mistake again. This new rule is one that they’re judged against.

When I realised how close a parallel this, a very cold shiver went down my spine. But I also realised how much I’d been doing to break out of this system, by treating students as equals with mutual respect, by listening and trying to be more flexible, by interpreting a more rigid pedagogical structure through filters that met everyone’s requirements. But unless I change the system, I am merely one of the “good” overseers on a penal plantation. When the students leave my care, if I know they are being treated badly, I am still culpable.

As I started with, valuing knowledge, accuracy, being productive (in an academic sense), being curious and being creative are all things that we should be passing on from our culture but these are very hard things to pass on with a punishment/reward modality as they are all cognitive in aspect. What is far easier to do is to pass on culture such as sitting silently, being bound by late penalties, conformity to the rules and the worst excesses of the Banking model of education (after Freire) where students are empty receiving objects that we, as teachers, fill up. There is no agency in such a model, nor room for creativity. The jug does not choose the liquid that fills it.

It is easy to see examples all around us of the level of disrespect levelled at colonised peoples, from the mindless (and well-repudiated) nonsense spouted in Australian newspapers about Aboriginal people to the racist stereotyping that persists despite the overwhelming evidence of equality between races and genders. It is also as easy to see how badly students can be treated by some staff. When we write off a group of students because they are ‘bad students’ then we have made them part of a group that we don’t respect – and this empowers us to not have to treat them as well as we treat ourselves.

We have to start from the basic premise that our students are at University because they want to be like us, but like the admirable parts of us, not the conformist, factory model, industrial revolution prison aspects. They are junior lawyers, young engineers, apprentice architects when they come to us – they do not have to prove their humanity in order to be treated with respect. However, this does have to be mutual and it’s important to reflect upon the role that we have as a mentor, someone who has greater knowledge in an area and can share it with a more junior associate to bring them up to the same level one day.

If we regard students as being worthy of respect, as being potential peers, then we are more likely to treat them with a respect that engenders a reciprocal relationship. Treat your students like idiots and we all know how that goes.

The colonial mindset is poisonous because of the inherent superiority and because of the value of conformity to imposed rules above the potential to be gained from incorporating new and useful aspects of other cultures. There are many positive aspects of University culture but they can happily coexist with other educational traditions and cultures – the New Zealand higher educational system is making great steps in this direction to be able to respect both Maori tradition and the desire of young people to work in a westernised society without compromising their traditions.

We have to start from the premise that all people are equal, because to do otherwise is to make people unequal. We then must regard our students as ourselves, just younger, less experienced and only slightly less occasionally confused than we were at that age. We must carefully examine how we expose students to our important cultural aspects and decide what is and what is not important. However, if all we turn out at the end of a 3-4 year degree is someone who can perform a better model of piece work and is too heavily intimidated into conformity that they cannot do anything else – then we have failed our students and ourselves.

The game I mentioned, “Dog Eat Dog”, starts with a quote by a R. Zamora Linmark from his poem “They Like You Because You Eat Dog”. Linmark is a Filipino American poet, novelist, and playwright, who was educated in Honolulu. His challenging poem talks about the ways that a second-class citizenry are racially classified with positive and negative aspects (the exoticism is balanced against a ‘brutish’ sexuality, for example) but finishes with something that is even more challenging. Even when a native population fully assimilates, it is never enough for the coloniser, because they are still not quite them.

“They like you because you’re a copycat, want to be just like them. They like you because—give it a few more years—you’ll be just like them.

And when that time comes, will they like you more?”R. Zamora Linmark, “They Like You Because You Eat Dog”, from “Rolling the R’s”

I had a discussion once with a remote colleague who said that he was worried the graduates of his own institution weren’t his first choice to supervise for PhDs as they weren’t good enough. I wonder whose fault he thought that was?