The Kids are Alright (within statistical error)

Posted: April 21, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: blogging, community, data visualisation, design, education, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, reflection, thinking, tools 3 CommentsYou may have seen this quote, often (apparently inaccurately) attributed to Socrates:

“The children now love luxury; they have bad manners, contempt for authority; they show disrespect for elders and love chatter in place of exercise. Children are now tyrants, not the servants of their households. They no longer rise when elders enter the room. They contradict their parents, chatter before company, gobble up dainties at the table, cross their legs, and tyrannize their teachers.” (roughly 400BC)

Apparently this is either a paraphrase of Aristophanes or misquoted Plato – like all things attributed to Socrates, we have to remember that we don’t have his signature to any of them. However, it doesn’t really matter if Socrates said it because not only did Hesiod say something in 700BC:

“I see no hope for the future of our people if they are dependent on frivolous youth of today, for certainly all youth are reckless beyond words… When I was young, we were taught to be discreet and respectful of elders, but the present youth are exceedingly wise [disrespectful] and impatient of restraint”

And then we have Peter the Hermit in 1274AD:

“The world is passing through troublous times. The young people of today think of nothing but themselves. They have no reverence for parents or old age. They are impatient of all restraint. They talk as if they knew everything, and what passes for wisdom with us is foolishness with them. As for the girls, they are forward, immodest and unladylike in speech, behavior and dress.”

(References via the Wikiquote page of Socrates and a linked discussion page.)

Let me summarise all of this for you:

You dang kids! Get off my lawn.

As you know, I’m a facty-analysis kind of guy so I thought that, if these wise people were correct and every generation is steadily heading towards mental incapacity and moral turpitude, we should be able to model this. (As an aside, I love the word turpitude, it sounds like the state of mind a turtle reaches after drinking mineral spirits.)

So let’s do this, let’s assume that all of these people are right and that the youth are reckless, disrespectful and that this keeps happening. How do we model this?

It’s pretty obvious that the speakers in question are happy to set themselves up as people who are right, so let’s assume that a human being’s moral worth starts at 100% and that all of these people are lucky enough to hold this state. Now, since Hesiod is chronologically the first speaker, let’s assume that he is lucky enough to be actually at 100%. Now, if the kids aren’t alright, then every child born will move us away from this state. If some kids are ok, then they won’t change things. Of course, every so often we must get a good one (or Socrates’ mouthpiece and Peter the Hermit must be aliens) so there should be a case for positive improvement. But we can’t have a human who is better than 100%, work with me here, and we shall assume that at 0% we have the worst person you can think of.

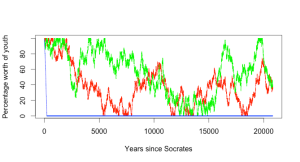

What we are now modelling is a random walk, starting at 100 and then adding some combination of -1, 0 or 1 at some regular interval. Let me cut to the chase and show you what this looks like, when modelled. I’ve assumed, for ease of modelling, that we make the assessment of the children every year and we have at most a 1 percentile point shift in that year, whatever other assumptions I made. I’ve provided three different models, one where the kids are terrible – we choose very year from no change or a negative shift. The next model is that the kids have some hope but sometimes do nothing, and we choose from an improvement, no change or steady moral decline! The final model is one where we either go up or down. Let’s look at a random walk across all three models over the span of years from 700BC to today:

As you can see, if we take the dire predictions of the next generation as true, then it is only a few hundred years before everything collapses. However, as expected, random walks over this range move around and hit a range of values. (Right now, you should look up Gambler’s Ruin to see why random walks are interesting – basically, over an infinite time, you’d expect to hit all of the values in the range from 0 to 100 an infinite number of times. This is why gamblers with small pots of money struggle against casinos with effectively infinite resources. Maths.)

But we know that the ‘everything is terrible’ model doesn’t work because both Socrates and Peter the Hermit consider themselves to be moral and both lived after the likely ‘decline to zero’ point shown in the blue line. But what would happen over longer timeframes? Let’s look at 20,000 and 200,000 years respectively. (These are separately executed random walks so the patterns will be different in each graph.)

What should be apparent, even with this rather pedantic exploration of what was never supposed to be modelled is that, even if we give credence to these particular commentators and we accept that there is some actual change that is measurable and shows an improvement or decline between generations, the negative model doesn’t work. The longer we run this, the more it will look like the noise that it is – and that is assuming that these people were right in the first place.

Personally, I think that the kids of this generation are pretty much the same as the one before, with some different adaptation to technology and societal mores. Would I have wasted time in lectures Facebooking if I had the chance? Well, I wasted it doing everything else so, yes, probably. (Look around your next staff meeting to see how many people are checking their mail. This is a technological shift driven by capability, not a sign of accelerating attention deficit.) Would I have spent tons of times playing games? Would I? I did! They were just board, role-playing and simpler computer games. The kids are alright and you can see that from the graphs – within statistical error.

Every time someone tells me that things are different, but it’s because the students are not of the same calibre as the ones before… well, I look at these quotes over the past 2,500 and I wonder.

And I try to stay off their lawn.

Tell us we’re dreaming.

Posted: April 21, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, education, Generation Why, higher education, reflection, resources, thinking, work/life balance, workload 2 CommentsI recently read an opinion piece in the Australian national newspaper, the conveniently named “The Australian”, on funding school reform. The piece, entitled “School Reform must be funded” and sub-titled “But maybe we need fewer academics thinking up ways to spend our taxes”, written by Cassandra Wilkinson, identified that the coming cuts to higher education because of the apparent impossibility of paying for school reforms in any other way. No-one, sensible, is arguing that the school cuts can come out of thin air, I make explicit reference to realities such as this in my previous post, but it does appear that Cassandra is attempting to place the blame squarely on the shoulders of the academics, for this sorry state of affairs (“the growing influence of the university sector on early childhood and school education is partly responsible for the now necessary cuts to higher education.”, from the article).

It is the professionalisation of teaching, and the intervention of education academics to convince governments that early educational investment, potentially at the expense of the family unit’s role in child rearing, that has convinced governments that money must be spent here – therefore, it is our fault that our argument is leading to money coming out of our pockets. I cannot think of a more amazing piece of victim blaming, recently, but then again I generally don’t read the opinion section of The Australian!

Now, you may immediately say “You must be quoting her out of context”, here is another extract from this rather short opinion piece:

“In addition to the public costs being generated by education academics, we have public health academics driving an expensive “preventative health” agenda that includes mental health checks for kids and public advertising about the calorie content of pizza; safety academics driving up the cost of road building and tripling the price of trampolines, which now come with fencing and crash mats; and sustainability academics driving up the cost of housing.”

Not only are people concerned about education driving up the cost of education but we have increased all other prices through our short-sighted adherence to preventative health, safety and sustainability! I keep thinking that Wilkinson, who has some quiet excellent social project credentials if I have researched the correct Cassandra Wilkinson, must be making a satirical comment here but, either my humour is failing (entirely possible), she has been edited (entirely possible) or she is completely serious and we in higher education have brought doom upon our heads by dint of doing our job. The piece finishes with:

“It may well be that the real efficiency savings will derive from a university sector employing slightly fewer academics to dream up new ways for governments to spend taxpayers money.”

and whether this is intended to be satire or not, this statement does raise my hackles.

Right now, most of the academics I know are trying to dream up ways to meet our obligations to our students in terms of a high-quality, useful and valuable education under existing restrictions. The only tax spending we’re trying to do is on the things that we can barely afford to do on the monies we get. I’m assuming that Cassandra is being satirical but is just not very good at it – or is assuming the role of her namesake, in that no-one will actually take her seriously, which is a shame as the approach that she seems to be supporting is not just saying that the only place this money can come from is higher ed, but that we should shut up because of how much we’re costing decent, family-centered Australians. If only I had that many column inches in a large-scale distribution paper to put my case that, maybe, people should stop talking about what they think we’re doing, or their fuzzy memories of old Uni days and bad movies, and come down and see what we’re doing now. Shadow me for a month. Bring running shoes. But, hey, maybe I’m just lazy, soft and dreamy. How would I know?

The rich dream of luxuries, the poor dream of staples. We are dreaming of having enough to do our jobs adequately and these are not the dreams of rich people.

Maybe I’m just too tired right now to see her humour in all of this. I seriously hope that I’ve just got the wrong end of the stick, because if this is what the social progressives are saying, then we may as well close up shop now.

Compound Interest, False Laws and Shiny Taps

Posted: April 14, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, education, ethics, Generation Why, higher education, reflection, thinking 2 Comments(I return with a very long rant about funding cuts in higher education. Rather political so feel free to not read if you’re after my edu research and praxis stuff.)

Like most governments, the Australian Federal Government is making spending cuts at the moment. Unlike most countries, Australia is actually doing pretty well but, unfortunately, we have a federal election coming up this year and we are losing the ability to do mathematics in a sea of politics. One initiative that has just been announced is increased funding to schools in line with the Gonski review – hooray! The only problem is that they are cutting University funding to do this – wait, what? (Four different links from different news organisations, for your delectation.) School funding will go up $14.5bn over six years and, for my sector, “$2.8 billion in cuts to universities, discounts for families paying upfront HECS fees, self education tax deduction changes and converting a student scholarship scheme into a loans scheme” (from the last link). The University cuts include a $900M “University funding efficiency dividend“.

Efficiency dividend?

For those who, like me, have just seen the Australian University sector be scheduled for a 2% efficiency dividend you may have wondered “What does this actually mean?” You can read about this concept at this web site, but let me summarise it here. The efficiency dividend is defined as an ‘annual reduction in funding for the overall running costs of an agency’ so, if you were looking for a different way to say this, you might say ‘annual scheduled operational budget cut’. This is tied together with the concept of efficiency and is based on the assumption that a (public service) department will become steadily more productive over time and thus we can cut resources and still get the same level of output. Money saved here can then be used for other high priority projects. What this means to me is that we, as Universities, will get less money and must cut our resourcing but have to maintain our quality of outputs because of a staggering belief that there is some sort of dependable Moore’s Law productivity gain for public sector and quasi-government agencies – and this includes Universities. (Moore’s Law is “the observation that over the history of computing hardware, the number of transistors on integrated circuits doubles approximately every two years” – Wikipedia – and is often reinterpreted as “computers double in speed every 18 months”. Moore’s Law is actually an observation and people who use it as a reliable prediction of the future are missing the point. I note that the semiconductor industry is starting to think that the doubling rate is dropping to ever three years, which makes this even less of a “Law”.)

Let me clear up something straight away. Yes, the schools need more funds, teachers need more pay and this is essential to our future and stability as a nation. And, yes, I know the money has to come from somewhere, but if we are going to trim under the illusion of doing it along productivity maintenance lines then let us clear up some fundamental misconceptions so that we know whether we are surgically trimming or whole carcass butchering.

It’s worth reading the whole document because it contains gems such as “The efficiency dividend also recognises that the public sector does not face the same incentives as the private sector to pass on gains from increased productivity in the form of lower prices.” Well, this is true, the public service is not in competition and the same is, to a reasonable extent, still true of schools. Most students will go to a mainstream public school funded by government and determined by where they live. Some will go to private schools that still get a sizeable chunk of change from the government. It is, however, unlikely that the majority of students will migrate to a different state to attend school and, conversely, setting up competing schools is a highly regulated activity (as one would actually hope) so competition is kept at bay.

What gets cut, usually? Let me quote from the document:

The efficiency dividend is primarily applied to departmental appropriations including ‘funding for depreciation/amortisation, Departmental and Administered Capital Budgets and Collection Development Acquisition Budgets’. [21] The dividend is also applied to ‘appropriations for other expenses of a departmental outputs type nature’ and ‘funding for all new policy initiatives following the year in which the new measures are introduced into those appropriations’.[22]

Capital budgets, acquisition budgets, expenses incurred for outputs and new policy initiatives. At a time when the Federal Government is, at the same time, trying to increase the number of Australians in tertiary education and all of us a trying to work out if MOOC is some kind of long con or useful technology, a 2% cut in our ability to buy things, innovate and improve our teaching and research (our outputs) seems… odd.

It’s worth remembering that the Higher education sector is actually in a highly competitive market – at the national and international level. We face competition from other states and countries and if you think that the Group of 8 (the notional top 8 Universities in Australia) and the “almost 8s”, who are eyeing “weak” members in the group, aren’t already storing their powder and trimming sails to politely engage each other in a rather genteel multi-way replay of the battle for dominance of the trade routes, then you haven’t been paying much attention. On top of that, investment targeted at increasing international standing in the various lists is already redirecting funds. Putting on an ‘upwards trajectory’ Professor with lots of citations? Not only is that almost a no-brainer but many places will have special funds to target this. Where does that money come from? Existing staffing not being refilled, contracts not being renewed, outsourcing to a partial position at corporate rates to reduce overhead. I’m lucky in that we are not yet in the full grip of this – but take away 2% of our resource growth and development funding annually and it will be rampant soon enough. You know all of the travel I do? Almost all of the money for that comes from months or years of prior work, hard-fought competitive grants with travel components and the Uni pays for very little of it – 10 years ago they would have funded several of my trips. I’m lucky in that I got a start when the money was flowing because, right now, we’re beyond lean and mean and heading towards emaciated and angry. Yet, I come from a relatively well-off Uni with a fairly good market position. We’re only grumpy but I have colleagues at other places who are struggling to keep enough people to produce any outputs, let alone the high quality ones magically predicted by the efficiency dividend document.

And, please, let’s not forget that the vast majority of educators are already working well over allotted time, using their own resources, haven’t had real pay raises in many places for years and, in some cases, supporting their own students in order to keep education going. This is already unsustainable, for both productivity and quality of product, in the long term – making it harder isn’t sensible or in anyone’s long term interests. I’m sick of going to conferences to hear how many people have been made redundant in the past year – but it’s a deep pit of the stomach sickness because I know it’s not going to stop.

But let’s step sideways to look at a strange mechanism – the notion of fungible product. Something is fungible if units of it can be substituted. Crude oil is the common example used here – a barrel of crude is a barrel of crude. Can we make all of our products mutually substitutable, because that is one of the obvious ways that we somehow maintain the same output despite cutting back our production. If we designate the annual productivity of a government department as P, then this total productivity is made up of sub-tasks, p1…pn, which have some notional ‘benefit’. There are two ways we can increase the productivity – we can add more ‘p’s in later years, so we have pn+1 and so on, or we can increase the benefit of these sub-tasks. The productivity trade-off of the efficiency dividend assumes that, if it takes R resources to produce the ‘p’s, we can cut R by some value and somehow generate a subset of the ‘p’s that is still considered productive. However, if we had actually increased our productivity by increasing benefit (and let us assume that this maps to quality) then what we are now saying is that the cut in R means the removal of an existing service – not the removal of an added service. Now, yes, the obvious onus of this is on administrative efficiency and we can denote the administrative sub-services as ‘a’s. So P is now composed of the maximum number of ‘p’s and the minimum number of ‘a’s. Ultimately, we reduce down to one ‘a’ administrative service and we have the most efficient government department in the land – all but one of our efforts is directed at productivity. Hooray! The system works!

But this is wrong for two reasons. Firstly, the product of almost all of these areas is most certainly not fungible and we do not have a uniform value for quality, nor do we exist in a vacuum. Has it honestly been so long since “Yes Minister” that we have forgotten how important employment and transport are in marginal electorates? We don’t even have clean value propositions for those services that we wish to keep as benefit is so hard to pin down in a world where public money, public opinion and high profile representation intersect. Why are Unis being cut for schools? My dark suspicion is that this is the natural intersection of an election year and rather cynical calculation that more people have kids at schools than at Uni, hence this will please more voters. To meme for a moment, desperate government is desperate.

The second reason that this is wrong is that establishing the productivity of any given area is a highly controversial measure and tying a cut to reported productivity increases ignores any number of human factors, as well as compound interest. How long does it take a 2% annual ‘efficiency dividend’ to severely reduce the real budget? Let’s look at 25 years. After 25 years, your budget will be at 60% of its original figure. Please, stick your hand up if you provide me with a sound, evidence-based solution that will allow us to maintain the quality of the Universities with 60% of the cash. 3% per year? We’re under 50% of budget in 25 years. Managers are under pressure to report improvements in productivity but, having driven people to work harder, having already streamlined operations to do so, the reward is that, next year, it gets harder. As my colleagues in the US can tell you, there is a point at which you stop cutting fat and you start cutting flesh. In some parts of the US, they are nearly out of flesh and are using the bone saws to get at the marrow. That sound you hear from the disadvantaged states in the US is not the whistle of air escaping from the balloon, it is a straw sucking air from a hollow bone.

My friends, I am not the hardest working person I know, but I do know that I’m no longer shaking illnesses as quickly, my blood pressure is up, I don’t sleep as well and, given half a chance, I will spend the whole weekend working, only to discover that there is always six months more work ahead of me. I’m not sure I have 2% more to give – perhaps it is time I stepped aside for someone hungrier or better (or cheaper)? Will this give us the efficiency that is sought, when we remove me and my 20-odd years of educational experience, 7 at the higher ed level?

An interesting subsection of the document I’ve referred to is that exemptions are granted – either recurring or annually. Nine agencies continue to be exempt from efficiency dividends for a variety of reasons. Three are fully exempt: ABC, SBS (both broadcasters who are exempt because of election promises), Safe Work Australia (co-funded State/Fed). Six are partially exempt: CSIRO and Aust Inst of Marine Science, Australian Council of the Arts, Customs and Border Protection, ANSTO and DoD – all of whom can pretty much keep their cuts away from major operational areas because of FEAR to a large extent. (It’s always sad when xenophobia becomes one of the facets you depend upon for continued funding.)

In 2008-09, the following got a one year reprieve: Australian Trade Commission; Australian Fair Pay Commission Secretariat; Workplace Authority; Australian Prudential Regulation Authority; Australian Sports Commission

In 2012-13, another set with one year reprieves: Family Court of Australia; Federal Court of Australia; High Court of Australia; Federal Magistrates Court; Administrative Appeals Tribunal; Social Security Appeals Tribunal; National Native Title Tribunal; Migration Review Tribunal—Refugee Review Tribunal; Australian National Maritime Museum; National Gallery of Australia; National Museum of Australia; National Library of Australia; Australia Council for the Arts; Australian Film Television and Radio School; Australian Sports Commission; National Film and Sound Archive; National Archives of Australia; Old Parliament House (Museum of Australian Democracy); Screen Australia; Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies; Australian War Memorial; Torres Strait Regional Authority; Aboriginal Hostels Limited; Indigenous Business Australia; Indigenous Land Corporation; Australian Communications and Media Authority.

Confusingly, if you look at that list, the entire Australian higher education sector is ranked slightly lower in priority than a vast number of bodies who depend upon our scholarship and educational infrastructure and our increasingly (and overdue) embracing of more inclusiveness and outreach into non-traditional pathways. Yes, schools need money and, yes, money has to come from somewhere, but why are we interfering with one of the receiving points of the system we’re trying to fix!

This is, frankly, silly. When you have a water crisis, you have to find the water, make it drinkable and get it to people who need it. The pipeline is a great way to do this because it centralises your maintenance expenses and works as a distribution mechanism with much lower cost than container transport – lower waste footprint as well! But building giant shiny new taps in the city does not mean that the water will just magically appear with no intervening pipeline or treatment. Neither does building an intake in the ocean automatically mean that a disconnected sink in Wagga will suddenly yield clean water. Education is a pipeline from which we can only lose students. We start with a number at the start of primary school and we’ve lost a lot (over 80%) by the time we get to University. Transitioning students into higher ed is non-trivial, retention is not guaranteed and sometimes it’s hard enough to be 17 without throwing our stuff on top. Reducing our ability to innovate is making a hard situation harder. Reducing our ability to invest for the future doesn’t just hurt us now, it hurts us for decades to come.

Education costs money and we are already well beyond the salad days fondly remembered by politicians who were last in our system 20-30 years ago. Every professor we lose takes 20-25 years of knowledge with her or him. Every teaching assistant we don’t replace increases the student-teacher ratio and this, in turn, will have an effect in the future. Every time our educational system shrinks, we reduce the outputs in terms of graduates, therefore in terms of professionals and academics, which gives us a generational problem because, on this trend, that 25 year timeframe doesn’t just give us 60% of our budget, it gives us much fewer potential staff and this just keeps happening.

Education is the core of civilisation. Education should not be a tool of class warfare, a cheap grab at votes or overseen by people who wilfully refuse to think in anything other than 3-4 year terms – and I paint all sides of politics with this brush. Get some generational focus issues going – 25 year projects with no political currency or opportunism. Yes, let’s fix up the schools, but let’s not do so in order to funnel students into work training schemes to produce cheap labour with no hope of anything beyond that. Let’s look at education as what it is – a lifelong endeavour made up of schools, communities, Universities, businesses and government working together.

Goodness knows, we’re all working hard enough already. Maybe working together might give us enough total effort to do something about this.

SIGCSE 2013: The Revolution Will Be Televised, Perspectives on MOOC Education

Posted: March 17, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, community, education, educational research, ethics, Generation Why, higher education, learning, measurement, moocs, sigcse, teaching, teaching approaches, tools 4 CommentsLong time between posts, I realise, but I got really, really unwell in Colorado and am still recovering from it. I attended a lot of interesting sessions at SIGCSE 2013, and hopefully gave at least one of them, but the first I wanted to comment on was a panel with Mehram Sahami, Nick Parlante, Fred Martin and Mark Guzdial, entitled “The Revolution Will Be Televised, Perspectives on MOOC Education”. This is, obviously, a very open area for debate and the panelists provided a range of views and a lot of information.

Mehram started by reminding the audience that we’ve had on-line and correspondence courses for some time, with MIT’s OpenCourseWare (OCW) streaming video from the 1990s and Stanford Engineering Everywhere (SEE) starting in 2008. The SEE lectures were interesting because viewership follows a power law relationship: the final lecture has only 5-10% of the views of the first lecture. These video lectures were being used well beyond Stanford, augmenting AP courses in the US and providing entire lecture series in other countries. The videos also increased engagement and the requests that came in weren’t just about the course but were more general – having a face and a name on the screen gave people someone to interact with. From Mehram’s perspective, the challenges were: certification and credit, increasing the richness of automated evaluation, validated peer evaluation, and personalisation (or, as he put it, in reality mass customisation).

Nick Parlante spoke next, as an unashamed optimist for MOOC, who has the opinion that all the best world-changing inventions are cheap, like the printing press, arabic numerals and high quality digital music. These great ideas spread and change the world. However, he did state that he considered artisinal and MOOC education to be very different: artisinal education is bespoke, high quality and high cost, where MOOCs are interesting for the massive scale and, while they could never replace artisinal, they could provide education to those who could not get access to artisinal.

It was at this point that I started to twitch, because I have heard and seen this argument before – the notion that MOOC is better than nothing, if you can’t get artisinal. The subtext that I, fairly or not, hear at this point is the implicit statement that we will never be able to give high quality education to everybody. By having a MOOC, we no longer have to say “you will not be educated”, we can say “you will receive some form of education”. What I rarely hear at this point is a well-structured and quantified argument on exactly how much quality slippage we’re tolerating here – how educational is the alternative education?

Nick also raised the well-known problems of cheating (which is rampant in MOOCs already before large-scale fee paying has been introduced) and credentialling. His section of the talk was long on optimism and positivity but rather light on statistics, completion rates, and the kind of evidence that we’re all waiting to see. Nick was quite optimistic about our future employment prospects but I suspect he was speaking on behalf of those of us in “high-end” old-school schools.

I had a lot of issues with what Nick said but a fair bit of it stemmed from his examples: the printing press and digital music. The printing press is an amazing piece of technology for replicating a written text and, as replication and distribution goes, there’s no doubt that it changed the world – but does it guarantee quality? No. The top 10 books sold in 2012 were either Twilight-derived sadomasochism (Fifty Shades of Unncessary) or related to The Hunger Games. The most work the printing presses were doing in 2012 was not for Thoreau, Atwood, Byatt, Dickens, Borges or even Cormac McCarthy. No, the amazing distribution mechanism was turning out copy after copy of what could be, generously, called popular fiction. But even that’s not my point. Even if the printing presses turned out only “the great writers”, it would be no guarantee of an increase in the ability to write quality works in the reading populace, because reading and writing are different things. You don’t have to read much into constructivism to realise how much difference it makes when someone puts things together for themselves, actively, rather than passively sitting through a non-interactive presentation. Some of us can learn purely from books but, obviously, not all of us and, more importantly, most of us don’t find it trivial. So, not only does the printing press not guarantee that everything that gets printed is good, even where something good does get printed, it does not intrinsically demonstrate how you can take the goodness and then apply it to your own works. (Why else would there be books on how to write?) If we could do that, reliability and spontaneously, then a library of great writers would be all you needed to replace every English writing course and editor in the world. A similar argument exists for the digital reproduction of music. Yes, it’s cheap and, yes, it’s easy. However, listening to music does not teach you to how write music or perform on a given instrument, unless you happen to be one of the few people who can pick up music and instrumentation with little guidance. There are so few of the latter that we call them prodigies – it’s not a stable model for even the majority of our gifted students, let alone the main body.

Fred Martin spoke next and reminded us all that weaker learners just don’t do well in the less-scaffolded MOOC environment. He had used MOOC in a flipped classroom, with small class sizes, supervision and lots of individual discussion. As part of this blended experience, it worked. Fred really wanted some honest figures on who was starting and completing MOOCs and was really keen that, if we were to do this, that we strive for the same quality, rather than accepting that MOOCs weren’t as good and it was ok to offer this second-tier solution to certain groups.

Mark Guzdial then rounded out the panel and stressed the role of MOOCs as part of a diverse set of resources, but if we were going to do that then we had to measure and report on how things had gone. MOOC results, right now, are interesting but fundamentally anecdotal and unverified. Therefore, it is too soon to jump into MOOC because we don’t yet know if it will work. Mark also noted that MOOCs are not supporting diversity yet and, from any number of sources, we know that many-to-one (the MOOC model) is just not as good as 1-to-1. We’re really not clear if and how MOOCs are working, given how many people who do complete are actually already degree holders and, even then, actual participation in on-line discussion is so low that these experienced learners aren’t even talking to each other very much.

It was an interesting discussion and conducted with a great deal of mutual respect and humour, but I couldn’t agree more with Fred and Mark – we haven’t measured things enough and, despite Nick’s optimism, there are too many unanswered questions to leap in, especially if we’re going to make hard-to-reverse changes to staffing and infrastructure. It takes 20 years to train a Professor and, if you have one that can teach, they can be expensive and hard to maintain (with tongue firmly lodged in cheek, here). Getting rid of one because we have a promising new technology that is untested may save us money in the short term but, if we haven’t validated the educational value or confirmed that we have set up the right level of quality, a few years now from now we might discover that we got rid of the wrong people at the wrong time. What happens then? I can turn off a MOOC with a few keystrokes but I can’t bring back all of my seasoned teachers in a timeframe less than years, if not decades.

I’m with Mark – the resource promise of MOOCs is enormous and they are part of our future. Are they actually full educational resources or courses yet? Will they be able to bring education to people that is a first-tier, high quality experience or are we trapped in the same old educational class divisions with a new name for an old separation? I think it’s too soon to tell but I’m watching all of the new studies with a great deal of interest. I, too, am an optimist but let’s call me a cautious one!

Expressiveness and Ambiguity: Learning to Program Can Be Unnecessarily Hard

Posted: January 23, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, collaboration, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools Leave a commentOne of the most important things to be able to do in any profession is to think as a professional. This is certainly true of Computer Science, because we have to spend so much time thinking as a Computer Scientist would think about how the machine will interpret our instructions. For those who don’t program, a brief quiz. What is the value of the next statement?

What is 3/4?

No doubt, you answered something like 0.75 or maybe 75% or possibly even “three quarters”? (And some of you would have said “but this statement has no intrinsic value” and my heartiest congratulations to you. Now go off and contemplate the Universe while the rest of us toil along on the material plane.) And, not being programmers, you would give me the same answer if I wrote:

What is 3.0/4.0?

Depending on the programming language we use, you can actually get two completely different answers to this apparently simple question. 3/4 is often interpreted by the computer to mean “What is the result if I carry out integer division, where I will only tell you how many times the denominator will go into the numerator as a whole number, for 3 and 4?” The answer will not be the expected 0.75, it will be 0, because 4 does not go into 3 – it’s too big. So, again depending on programming language, it is completely possible to ask the computer “is 3/4 equivalent to 3.0/4.0?” and get the answer ‘No’.

This is something that we have to highlight to students when we are teaching programming, because very few people use integer division when they divide one thing by another – they automatically start using decimal points. Now, in this case, the different behaviour of the ‘/’ is actually exceedingly well-defined and is not all ambiguous to the computer or to the seasoned programmer. It is, however, nowhere near as clear to the novice or casual observer.

I am currently reading Stephen Ramsay’s excellent “Reading Machines: Towards an Algorithmic Criticism” and it is taking me a very long time to read an 80 page book. Why? Because, to avoid ambiguity and to be as expressive and precise as possible, he has used a number of words and concepts with which I am unfamiliar or that I have not seen before. I am currently reading his book with a web browser and a dictionary because I do not have a background in literary criticism but, once I have the building blocks, I can understand his argument. In other words, I am having to learn a new language in order to read a book for that new language community. However, rather than being irked that “/” changes meaning depending on the company it keeps, I am happy to learn the new terms and concepts in the space that Ramsay describes, because it is adding to my ability to express key concepts, without introducing ambiguous shadings of language over things that I already know. Ramsay is not, for example, telling me that “book” no longer means “book” when you place it inside parentheses. (It is worth noting that Ramsay discusses the use of constraint as a creative enhancer, a la Oulipo, early on in the book and this is a theme for another post.)

The usual insult at this point is to trot out the accusation of jargon, which is as often a statement that “I can’t be bothered learning this” than it is a genuine complaint about impenetrable prose. In this case, the offender in my opinion is the person who decided to provide an invisible overloading of the “/” operator to mean both “division” and “integer division”, as they have required us to be aware of a change in meaning that is not accompanied by a change in syntax. While this isn’t usually a problem, spoken and written languages are full of these things after all, in the computing world it forces the programmer to remember that “/” doesn’t always mean “/” and then to get it the right way around. (A number of languages solve this problem by providing a distinct operator – this, however, then adds to linguistic complexity and rather than learning two meanings, you have to learn two ‘words’. Ah, no free lunch.) We have no tone or colour in mainstream programming languages, for a whole range of good computer grammar reasons, but the absence of the rising tone or rising eyebrow is sorely felt when we encounter something that means two different things. The net result is that we tend to use the same constructs to do the same thing because we have severe limitations upon our expressivity. That’s why there are boilerplate programmers, who can stitch together a solution from things they have already seen, and people who have learned how to be as expressive as possible, despite most of these restrictions. Regrettably, expressive and innovative code can often be unreadable by other people because of the gymnastics required to reach these heights of expressiveness, which is often at odds with what the language designers assumed someone might do.

We have spent a great deal of effort making computers better at handling abstract representations, things that stand in for other (real) things. I can use a name instead of a number and the computer will keep track of it for me. It’s important to note that writing int i=0; is infinitely preferable to typing “0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000” into the correct memory location and then keeping that (rather large number) address written on a scrap of paper. Abstraction is one of the fundamental tools of modern programming, yet we greatly limit expressiveness in sometimes artificial ways to reduce ambiguity when, really, the ambiguity does seem a little artificial.

One of the nastiest potential ambiguities that shows up a lot is “what do we mean by ‘equals'”. As above, we already know that many languages would not tell you that “3/4 equals 3.0/4.0” because both mathematical operations would be executed and 0 is not the same as 0.75. However, the equivalence operator is often used to ask so many different questions: “Do these two things contain the same thing?”, “Are these two things considered to be the same according to the programmer?” and “Are these two things actually the same thing and stored in the same place in memory?”

Generally, however, to all of these questions, we return a simple “True” or “False”, which in reality reflects neither the truth nor the falsity of the situation. What we are asking, respectively, is “Are the contents of these the same?” to which the answer is “Same” or “Different”. To the second, we are asking if the programmer considers them to be the same, in which case the answer is really “Yes” or “No” because they could actually be different, yet not so different that the programmer needs to make a big deal about it. Finally, when we are asking if two references to an object actually point to the same thing, we are asking if they are in the same location or not.

There are many languages that use truth values, some of them do it far better than others, but unless we are speaking and writing in logical terms, the apparent precision of the True/False dichotomy is inherently deceptive and, once again, it is only as precise as it has been programmed to be and then interpreted, based on the knowledge of programmer and reader. (The programming language Haskell has an intrinsic ability to say that things are “Undefined” and to then continue working on the problem, which is an obvious, and welcome, exception here, yet this is not a widespread approach.) It is an inherent limitation on our ability to express what is really happening in the system when we artificially constrain ourselves in order to (apparently) reduce ambiguity. It seems to me that we have reduced programmatic ambiguity, but we have not necessarily actually addressed the real or philosophical ambiguity inherent in many of these programs.

More holiday musings on the “Python way” and why this is actually an unreasonable demand, rather than a positive feature, shortly.

Thanks for the exam – now I can’t help you.

Posted: December 31, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, tools, universal principles of design, vygotsky, workload 1 CommentI have just finished marking a pile of examinations from a course that I co-taught recently. I haven’t finalised the marks but, overall, I’m not unhappy with the majority of the results. Interestingly, and not overly surprisingly, one of the best answered sections of the exam was based on a challenging essay question I set as an assignment. The question spans many aspects of the course and requires the student to think about their answer and link the knowledge – which most did very well. As I said, not a surprise but a good reinforcement that you don’t have to drill students in what to say in the exam, but covering the requisite knowledge and practising the right skills is often helpful.

However, I don’t much like marking exams and it doesn’t come down to the time involved, the generally dull nature of the task or the repetitive strain injury from wielding a red pen in anger, it comes down to the fact that, most of the time, I am marking the student’s work at a time when I can no longer help him or her. Like most exams at my Uni, this was the terminal examination for the course, worth a substantial amount of the final marks, and was taken some weeks after teaching finished. So what this means is that any areas I identify for a given student cannot now be corrected, unless the student chooses to read my notes in the exam paper or come to see me. (Given that this campus is international, that’s trickier but not impossible thanks to the Wonders of Skypenology.) It took me a long time to work out exactly why I didn’t like marking, but when I did, the answer was obvious.

I was frustrated that I couldn’t actually do my job at one of the most important points: when lack of comprehension is clearly identified. If I ask someone a question in the classroom, on-line or wherever, and they give me an answer that’s not quite right, or right off base, then we can talk about it and I can correct the misunderstanding. My job, after all, is not actually passing or failing students – it’s about knowledge, the conveyance, construction and quality management thereof. My frustration during exam marking increases with every incomplete or incorrect answer I read, which illustrates that there is a section of the course that someone didn’t get. I get up in the morning with the clear intention of being helpful towards students and, when it really matters, all I can do is mark up bits of paper in red ink.

Quickly, Jones! Construct a valid knowledge framework! You’re in a group environment! Vygotsky, man, Vygotsky!

A student who, despite my sweeping, and seeping, liquid red ink of doom, manages to get a 50 Passing grade will not do the course again – yet this mark pretty clearly indicates that roughly half of the comprehension or participation required was not carried out to the required standard. Miraculously, it doesn’t matter which half of the course the student ‘gets’, they are still deemed to have attained the knowledge. (An interesting point to ponder, especially when you consider that my colleagues in Medicine define a Pass at a much higher level and in far more complicated ways than a numerical 50%, to my eternal peace of mind when I visit a doctor!) Yet their exam will still probably have caused me at least some gnashing of teeth because of points missed, pointless misstatement of the question text, obscure song lyrics, apologies for lack of preparation and the occasional actual fact that has peregrinated from the place where it could have attained marks to a place where it will be left out in the desert to die, bereft of the life-giving context that would save it from such an awful fate.

Should we move the exams earlier and then use this to guide the focus areas for assessment in order to determine the most improvement and develop knowledge in the areas in most need? Should we abandon exams entirely and move to a continuous-assessment competency based system, where there are skills and knowledge that must be demonstrated correctly and are practised until this is achieved? We are suffering, as so many people have observed before, from overloading the requirement to grade and classify our students into neatly discretised performance boxes onto a system that ultimately seeks to identify whether these students have achieved the knowledge levels necessary to be deemed to have achieved the course objectives. Should we separate competency and performance completely? I have sketchy ideas as to how this might work but none that survive under the blow-torches of GPA requirements and resource constraints.

Obviously, continuous assessment (practicals, reports, quizzes and so on) throughout the semester provide a very valuable way to identify problems but this requires good, and thorough, course design and an awareness that this is your intent. Are we premature in treating the exam as a closing-off line on the course? Do we work on that the same way that we do any assignment? You get feedback, a mark and then more work to follow-up? If we threw resourcing to the wind, could we have a 1-2 week intensive pre-semester program that specifically addressed those issues that students failed to grasp on their first pass? Congratulations, you got 80%, but that means that there’s 20% of the course that we need to clarify? (Those who got 100% I’ll pay to come back and tutor, because I like to keep cohorts together and I doubt I’ll need to do that very often.)

There are no easy answers here and shooting down these situations is very much in the fish/barrel plane, I realise, but it is a very deeply felt form of frustration that I am seeing the most work that any student is likely to put in but I cannot now fix the problems that I see. All I can do is mark it in red ink with an annotation that the vast majority will never see (unless they receive the grade of 44, 49, 64, 74 or 84, which are all threshold-1 markers for us).

Ah well, I hope to have more time in 2013 so maybe I can mull on this some more and come up with something that is better but still workable.

Thinking about teaching spaces: if you’re a lecturer, shouldn’t you be lecturing?

Posted: December 30, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design, vygotsky Leave a commentI was reading a comment on a philosophical post the other day and someone wrote this rather snarky line:

He’s is a philosopher in the same way that (celebrity historian) is a historian – he’s somehow got the job description and uses it to repeat the prejudices of his paymasters, flattering them into thinking that what they believe isn’t, somehow, ludicrous. (Grangousier, Metafilter article 123174)

Rather harsh words in many respects and it’s my alteration of the (celebrity historian)’s name, not his, as I feel that his comments are mildy unfair. However, the point is interesting, as a reflection upon the importance of job title in our society, especially when it comes to the weighted authority of your words. From January the 1st, I will be a senior lecturer at an Australian University and that is perceived differently where I am. If I am in the US, I reinterpret this title into their system, namely as a tenured Associate Professor, because that’s the equivalent of what I am – the term ‘lecturer’ doesn’t clearly translate without causing problems, not even dealing with the fact that more lecturers in Australia have PhDs, where many lecturers in the US do not. But this post isn’t about how people necessarily see our job descriptions, it’s very much about how we use them.

In many respects, the title ‘lecturer’ is rather confusing because it appears, like builder, nurse or pilot, to contain the verb of one’s practice. One of the big changes in education has been the steady acceptance of constructivism, where the learners have an active role in the construction of knowledge and we are facilitating learning, in many ways, to a greater extent than we are teaching. This does not mean that teachers shouldn’t teach, because this is far more generic than the binding of lecturers to lecturing, but it does challenge the mental image that pops up when we think about teaching.

If I asked you to visualise a classroom situation, what would you think of? What facilities are there? Where are the students? Where is the teacher? What resources are around the room, on the desks, on the walls? How big is it?

Take a minute to do just this and make some brief notes as to what was in there. Then come back here.

It’s okay, I’ll still be here!

Adelaide Computing Education Conventicle 2012: “It’s all about the people”

Posted: December 27, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: acec2012, advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, conventicle, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, reconciliation, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, universal principles of design 1 Commentacec 2012 was designed to be a cross-University event (that’s the whole point of the conventicles, they bring together people from a region) and we had a paper from the University of South Australia: ‘”It’s all about the people”; building cultural competence in IT graduates’ by Andrew Duff, Kathy Darzanos and Mark Osborne. Andrew and Kathy came along to present and the paper was very well received, because it dealt with an important need and a solid solution to address that need, which was inclusive, insightful and respectful.

For those who are not Australians, it is very important to remember that the original inhabitants of Australia have not fared very well since white settlement and that the apology for what happened under many white governments, up until very recently, was only given in the past decade. There is still a distance between the communities and the overall process of bringing our communities together is referred to as reconciliation. Our University has a reconciliation statement and certain goals in terms of representation in our staff and student bodies that reflect percentages in the community, to reduce the underrepresentation of indigenous Australians and to offer them the same opportunities. There are many challenges facing Australia, and the health and social issues in our indigenous communities are often exacerbated by years of poverty and a range of other issues, but some of the communities have a highly vested interest in some large-scale technical, ICT and engineering solutions, areas where indigenous Australians are generally not students. Professor Lester Irabinna Rigney, the Dean of Aboriginal Education, identified the problem succinctly at a recent meeting: when your people live on land that is 0.7m above sea level, a 0.9m sea-level rise starts to become of concern and he would really like students from his community to be involved in building the sea walls that address this, while we look for other solutions!

Andrea, Kathy and Mark’s aim was to share out the commitment to reconciliation across the student body, making this a whole of community participation rather than a heavy burden for a few, under the guiding statement that they wanted to be doing things with the indigenous community, rather than doing things to them. There’s always a risk of premature claiming of expertise, where instead of working with a group to find out what they want, you walk in and tell them what they need. For a whole range of very good and often heartbreaking reasons, the Australian indigenous communities are exceedingly wary when people start ordering them about. This was the first thing I liked about this approach: let’s not make the same mistakes again. The authors were looking for a way to embed cultural awareness and the process of reconciliation into the curriculum as part of an IT program, sharing it so that other people could do it and making it practical.

Their key tenets were:

- It’s all about the diverse people. They developed a program to introduce students to culture, to give them more than one world view of the dominant culture and to introduce knowledge of the original Australians. It’s an important note that many Australians have no idea how to use certain terms or cultural items from indigenous culture, which of course hampers communication and interaction.

For the students, they were required to put together an IT proposal, working with the indigenous community, that they would implement in the later years of their degree. Thus, it became part of the backbone of their entire program.

- Doing with [people], not to [people]. As discussed, there are many good reasons for this. Reduce the urge to be the expert and, instead, look at existing statements of right and how to work with other peplum, such as the UN rights of indigenous people and the UniSA graduate attributes. This all comes together in the ICUP – Indigenous Content in Undergraduate Program

How do we deal with information management in another culture? I’ve discussed before the (to many) quite alien idea that knowledge can reside with one person and, until that person chooses or needs to hand on that knowledge, that is the person that you need. Now, instead of demanding knowledge and conformity to some documentary standard, you have to work with people. Talking rather than imposing, getting the client’s genuine understanding of the project and their need – how does the client feel about this?

Not only were students working with indigenous people in developing their IT projects, they were learning how to work with other peoples, not just other people, and were required to come up with technologically appropriate solutions that met the client need. Not everyone has infinite power and 4G LTE to run their systems, nor can everyone stump up the cash to buy an iPhone or download apps. Much as programming in embedded systems shakes students out of the ‘infinite memory, disk and power’ illusion, working with other communities in Australia shakes them out of the single worldview and from the, often disrespectful, way that we deal with each other. The core here is thinking about different communities and the fact that different people have different requirements. Sometimes you have to wait to speak to the right person, rather than the available person.

The online forum has four questions that students have to find a solution to, where the forum is overseen by an indigenous tutor. The four questions are:

- What does culture mean to you?

- Post a cultural artefact that describes your culture?

- I came here to study Computer Science – not Aboriginal Australians?

- What are some of the differences between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians?

The first two are amazing questions – what is your answer to question number 2? The second pair of questions are more challenging and illustrate the bold and head-on approach of this participative approach to reconciliation. Reconciliation between all of the Australian communities requires everyone to be involved and, being honest, questions 3 and 4 are going to open up some wounds, drag some silly thinking out into the open but, most importantly, allow us to talk through issues of concern and confusion.

I suspect that many people can’t really answer question 4 without referring back to mid-50s archetypal depictions of Australian Aborigines standing on one leg, looking out over cliffs, and there’s an excellent ACMI (Australian Centre for the Moving Image) exhibit in Melbourne that discusses this cultural misappropriation and stereotyping. One of the things that resonated with me is that asking these questions forces people to think about these things, rather than repeating old mind grooves and received nonsense overheard in pubs, seen on TV and heard in racist jokes.

I was delighted that this paper was able to be presented, not least because the goal of the team is to share this approach in the hope of achieving even greater strides in the reconciliation process. I hope to be able to bring some of it to my Uni over the next couple of years.

John Henry Died

Posted: December 23, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, john henry, learning, meritocracy, principles of design, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, workload Leave a commentEvery culture has its myths and legends, especially surrounding those incredible individuals who stand out or tower over the rest of the society. The Ancient Greeks and Romans had their gods, demigods, heroes and, many times, cautionary tales of the mortals who got caught in the middle. Australia has the stories of pre- and post-federation mateship, often anti-authoritarian or highlighting the role of the larrikin. We have a lot of bushrangers (with suspiciously good hearts or reacting against terrible police oppression), Simpson and his donkey (a first world war hero who transported men to an aid station using his donkey, ultimately dying on the battlefield) and a Prime Minister who goes on YouTube to announce that she’s now convinced that the Mayans were right and we’re all doomed – tongue firmly in cheek. Is this the totality of the real Australia? No, but the stylised notion of ‘mateship’, the gentle knock and the “come off the grass, you officious … person” attitude are as much a part of how many Australians see themselves as shrimp on a barbie is to many US folk looking at us. In any Australian war story, you are probably more likely to hear about the terrible hangover the Gunner Suggs had and how he dragged his friend a kilometre over rough stones to keep him safe, than you are to hear about how many people he killed. (I note that this mateship is often strongly delineated over gender and racial lines, but it’s still a big part of the Australian story.)

The stores that we tell and those that we pass on as part of our culture strongly shape our culture. Look at Greek mythology and you see stern warnings against hubris – don’t rate yourself too highly or the gods will cut you down. Set yourself up too high in Australian culture and you’re going to get knocked down as well: a ‘tall poppies’ syndrome that is part cultural cringe, inherited from colonial attitudes to the Antipodes, part hubris and part cultural confusion as Anglo, Euro, Asian, African and… well, everyone, come to terms with a country that took the original inhabitants, the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, quite a while to adapt to. As someone who wasn’t born in Australia, like so many others who live here and now call themselves Australia, I’ve spent a long time looking at my adopted homeland’s stories to see how to fit. Along the way, because of travel, I’ve had the opportunity to look at other cultures as well: the UK, obviously as it’s drummed into you at school, and the US, because it interests me.

The stories of Horatio Alger, from the US, fascinate me, because of their repeated statement of the rags to riches story. While most of Alger’s protagonists never become amazingly wealthy, they rise, through their own merits, to take the opportunities presented to them and, because of this, a good man will always rise. This is, fundamentally, the American Dream – that any person can become President, effectively, through the skills that they have and through rolling up their sleeves. We see this Dream become ugly when any of the three principles no longer hold, in a framing I first read from Professor Harlon Dalton:

- The notion that we are judged solely on our merits:For this to be true, we must not have any bias, racist, gendered, religious, ageist or other. Given the recent ruling that an attractive person can be sacked, purely for being attractive and for providing an irresistible attraction for their boss, we have evidence that not only is this point not holding in many places, it’s not holding in ways that beggar belief.

- We will each have a fair opportunity to develop these merits:This assumes equal opportunity in terms of education, in terms of jobs, which promptly ignores things like school districts, differing property tax levels, teacher training approaches and (because of the way that teacher districts work) just living in a given state or country because your parents live there (and can’t move) can make the distance between a great education and a sub-standard child minding service. So this doesn’t hold either.

- Merit will out:Look around. Is the best, smartest, most talented person running your organisation or making up all of the key positions? Can you locate anyone in the “important people above me” who is holding that job for reasons other than true, relevant merit?

Australia’s myths are beneficial in some ways and destructive in others. For my students, the notion that we help each other, we question but we try to get things done is a positive interpretation of the mild anti-authoritarian mateship focus. The downside is drinking buddies going on a rampage and covering up for each other, fighting the police when the police are actually acting reasonably and public vandalism because of a desire to act up. The mateship myth hides a lot of racism, especially towards our indigenous community, and we can probably salvage a notion of community and collaboration from mateship, while losing some of the ugly and dumb things.

Horatio Alger myths would give hope, except for the bleak reality that many people face which is that it is three giant pieces of boloney that people get hit about the head with. If you’re not succeeding, then Horatio Alger reasoning lets us call you lazy or stupid or just not taking the opportunities. You’re not trying to pull yourself up by your bootstraps hard enough. Worse still, trying to meet up to this, sometimes impossible, guideline leads us into John Henryism. John Henry was a steel driver, who hammered and chiseled the rock through the mountains to build tunnels for the railroad. One day the boss brought in a steam driven hammer and John Henry bet that he could beat it, to show that he and his crew should not be replaced. After a mammoth battle between man and machine, John Henry won, only to die with the hammer in his hand.

Let me recap: John Henry died – and the boss still got a full day’s work that was equal to two steam-hammers. (One of my objections to “It’s a Wonderful Life” is that the rich man gets away with stealing the money – that’s not a fairy tale, it’s a nightmare!) John Henryism occurs when people work so hard to lift themselves up by their bootstraps that they nearly (or do) kill themselves. Men in their 50s with incredibly high blood pressure, ulcers and arthritis know what I’m talking about here. The mantra of the John Henryist is:

“When things don’t go the way that I want them to, that just makes me work even harder.”

There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with this when your goal is actually achievable and you apply this maxim in moderation. At its extreme, and for those people who have people standing on their boot caps, this is a recipe to achieve a great deal for whoever is benefiting from your labour.

And then dying.

As John Henry observes in the ballad (Springsteen version), “I’ll hammer my fool self to death”, and the ballad of John Henry is actually a cautionary tale to set your pace carefully because if you’re going to swing a hammer all day, every day, then you have to do it at a pace that won’t kill you. This is the natural constraint on Horatio Alger and balances all of the issues with merit and access to opportunity: don’t kill your “fool self” striving for something that you can’t achieve. It’s a shame, however, that the stories line up like this because there’s a lot of hopelessness sitting in that junction.

Dealing with students always makes me think very carefully about the stories I tell and the stories I live. Over the next few days, I hope to put together some thoughts on a 21st century myth form that inspires without demanding this level of sacrifice, and that encourages without forcing people into despair if existing obstacles block them – and it’s beyond their current control to shift. However, on that last point, what I’d really like to come up with is a story that encourages people to talk about obstacles and then work together to lift them out of the way. I do like a challenge, after all. 🙂

Vitamin Ed: Can It Be Extracted?

Posted: December 22, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, vygotsky, workload Leave a commentThere are a couple of ways to enjoy a healthy, balanced diet. The first is to actually eat a healthy, balanced diet made up from fresh produce across the range of sources, which requires you to prepare and cook foods, often changing how you eat depending on the season to maximise the benefit. The second is to eat whatever you dang well like and then use an array of supplements, vitamins, treatments and snake oil to try and beat your diet of monster burgers and gorilla dogs into something that will not kill you in 20 years. If you’ve ever bothered to look on the side of those supplements, vitamins, minerals or whatever, that most people have in their ‘medicine’ cabinets, you might see statements like “does not substitute for a balanced diet” or nice disclaimers like that. There is, of course, a reason for that. While we can be fairly certain about a range of deficiency disorders in humans, and we can prevent these problems with selective replacement, many other conditions are not as clear cut – if you eat a range of produce which contains the things that we know we need, you’re probably getting a slew of things that we also need but don’t make themselves as prominent.

In terms of our diet, while the debate rages about precisely which diet humans should be eating, we can have a fairly good stab at a sound basis from a dietician’s perspective built out of actual food. Recreating that from raw sugars, protein, vitamin and mineral supplements is technically possible but (a) much harder to manage and (b) nowhere near as satisfying as eating the real food, in most cases. Let’s nor forget that very few of us in the western world are so distant from our food that we regard it purely as fuel, with no regard for its presentation, flavour or appeal. In fact, most of us could muster a grimace for the thought of someone telling us to eat something because it was good for us or for some real or imagined medical benefit. In terms of human nutrition, we have the known components that we have to eat (sugars, proteins, fats…) and we can identify specific vitamins and minerals that we need to balance to enjoy good health, yet there is not shortage of additional supplements that we also take out of concern for our health that may have little or no demonstrated benefit, yet still we take them.

There’s been a lot of work done in trying to establish an evidence base for medical supplements and far more of the supplements fail than pass this test. Willow bark, an old remedy for pain relief, has been found to have a reliable effect because it has a chemical basis for working – evidence demonstrated that and now we have aspirin. Homeopathic memory water? There’s no reliable evidence for this working. Does this mean it won’t work? Well, here we get into the placebo effect and this is where things get really complicated because we now have the notion that we have a set of replacements that will work for our diet or health because they contain useful chemicals, and a set of solutions that work because we believe in them.

When we look at education, where it’s successful, we see a lot of techniques being mixed in together in a ‘natural’ diet of knowledge construction and learning. Face-to-face and teamwork, sitting side-by-side with formative and summative assessment, as part of discussions or ongoing dialogues, whether physical or on-line. Exactly which parts of these constitute the “balanced” educational diet? We already know that a lecture, by itself, is not a complete educational experience, in the same way that a stand-alone multiple-choice question test will not make you a scholar. There is a great deal of work being done to establish an evidence basis for exactly which bits work but, as MIT said in the OCW release, these components do not make up a course. In dietary terms, it might be raw fuel but is it a desirable meal? Not yet, most likely.

Now let’s get into the placebo side of the equation, where students may react positively to something just because it’s a change, not because it’s necessarily a good change. We can control for these effects, if we’re cautious, and we can do it with full knowledge of the students but I’m very wary of any dependency upon the placebo effect, especially when it’s prefaced with “and the students loved it”. Sorry, students, but I don’t only (or even predominantly) care if you loved it, I care if you performed significantly better, attended more, engaged more, retaining the information for longer, could achieve more, and all of these things can only be measured when we take the trouble to establish base lines, construct experiments, measure things, analyse with care and then think about the outcomes.

My major concern about the whole MOOC discussion is not whether MOOCs are good or bad, it’s more to do with:

- What does everyone mean when they say MOOC? (Because there’s variation in what people identify as the components)

- Are we building a balanced diet or are we constructing a sustenance program with carefully balanced supplements that might miss something we don’t yet value?

- Have we extracted the essential Vitamin Ed from the ‘real’ experience?

- Can we synthesise Vitamin Ed outside of the ‘real’ educational experience?

I’ve been searching for a terminological separation that allows me to separate ‘real’/’conventional’ learning experiences from ‘virtual’/’new generation’/’MOOC’ experiences and none of those distinctions are satisfying – one says “Restaurant meal” and the other says “Army ration pack” to me, emphasising the separation. Worse, my fear is that a lot of people don’t regard MOOC as ever really having Vitamin Ed inside, as the MIT President clearly believed back in 2001.

I suspect that my search for Vitamin Ed starts from a flawed basis, because it assumes a single silver bullet if we take a literal meaning of the term, so let me me spread the concept out a bit to label Vitamin Ed as the essential educational components that define a good learning and teaching experience. Calling it Vitamin Ed gives me a flag to wave and an analogue to use, to explain why we should be seeking a balanced diet for all of our students, rather than a banquet for one and dog food for the other.