The Bad Experience That Stays With You and the Legendary Bruce Springsteen.

Posted: January 30, 2014 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, awesomesauce, bruce springsteen, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, ethics, experience, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, reflection, springsteen, student perspective, teacher, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, workload 1 CommentI was talking with a friend of mine and we were discussing perceptions of maths and computing (yeah, I’m like this off duty, too) and she felt that she was bad at Maths. I commented that this was often because of some previous experience in school and she nodded and told me this story, which she’s given me permission to share with you now. (My paraphrasing but in her voice)

“When I was five, we got to this point in Math where I didn’t follow what was going on. We got to this section and it just didn’t make any sense to me. The teacher gave us some homework to do and I looked at it and I couldn’t do it but I didn’t want to hand in nothing. So I scrunched it up and put it in the bin. When the teacher asked for it back, I told her that I didn’t have it.

It turns out that the teacher had seen me put it in the bin and so she punished me. And I’ve never thought of myself as good at math since.”

Wow. I’m hard-pressed to think of a better way to give someone a complex about a subject. Ok, yes, my friend did lie to the teacher about not the work and, yes, it would have been better if she’d approached the teacher to ask for help – but given what played out, I’m not really sure how much it would have changed what happened. And, before we get too carried away, she was five.

Now this is all some (but not that many) years ago and a lot of things have changed in teaching, but all of us who stand up and call ourselves educations could do worse than remember Bruce Springsteen’s approach to concerts. Bruce plays a lot of concerts but, at each one, he tries to give his best because a lot of the people in the audience are going to their first and only Springsteen concert. It can be really hard to deal with activities that are disruptive, disobedient and possible deliberately so, but they may be masking fear, uncertainty and a genuine desire for the problem to go away because someone is overwhelmed. Whatever we get paid, that’s really one of the things we get paid to do.

We’re human. We screw up. We get tired. But unless we’re thing about and trying to give that Springsteen moment to every student, then we’re setting ourselves up to be giving a negative example. Somewhere down the line, someone’s going to find their life harder because of that – it may be us in the next week, it may be another teacher next year, but it will always be the student.

Bad experiences hang around for years. It would be great if there were fewer of them. Be awesome. Be Springsteen.

Enemies, Friends and Frenemies: Distance, Categorisation and Fun.

Posted: January 29, 2014 Filed under: Education | Tags: curriculum, data visualisation, design, education, educational problem, games, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools Leave a commentAs Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola wrote in “The Godfather Part II”:

… keep your friends close but your enemies closer.

(I bet you thought that was Sun Tzu, the author of “The Art of War”. So did I but this movie is the first use.)

I was thinking about this the other day and it occurred to me that this is actually a simple modelling problem. Can I build a model which will show the space around me and where I would expect to find friends and enemies? Of course, you might be wondering “why would you do this?” Well, mostly because it’s a little bit silly and it’s a way of thinking that has some fun attached to it. When I ask students to build models of the real world, where they think about how they would represent all of the important aspects of the problem and how they would simulate the important behaviours and actions seen with it, I often give them mathematical or engineering applications. So why not something a little more whimsical?

From looking at the quote, we would assume that there is some distance around us (let’s call it a circle) where we find everyone when they come up to talk to us, friend or foe, and let’s also assume that the elements “close” and “closer” refer to how close we let them get in conversation. (Other interpretations would have us living in a neighbourhood of people who hate us, while we have to drive to a different street to sit down for dinner with people who like us.) So all of our friends and enemies are in this circle, but enemies will be closer. That looks like this:

So now we have a visual model of what is going on and, if we wanted to, we could build a simple program that says something like “if you’re in this zone, then you’re an enemy, but if you’re in that zone then you’re a friend” where we define the zones in terms of nested circular regions. But, as we know, friend always has your back and enemies stab you in the back, so now we need to add something to that “ME” in the middle – a notion of which way I’m facing – and make sure that I can always see my enemies. Let’s make the direction I’m looking an arrow. (If I could draw better, I’d put glasses on the front. If you’re doing this in the classroom, an actual 3D dummy head shows position really well.) That looks like this:

Now our program has to keep track of which way we’re facing and then it checks the zones, on the understanding that either we’re going to arrange things to turn around if an enemy is behind us, or we can somehow get our enemies to move (possibly by asking nicely). This kind of exercise can easily be carried out by students and it raises all sorts of questions. Do I need all of my enemies to be closer than my friends or is it ok if the closest person to me is an enemy? What happens if my enemies are spread out in a triangle around me? Is they won’t move, do I need to keep rotating to keep an eye on them or is it ok if I stand so that they get as much of my back as they can? What is an acceptable solution to this problem? You might be surprised how much variation students will suggest in possible solutions, as they tell you what makes perfect sense to them for this problem.

When we do this kind of thing with real problems, we are trying to specify the problem to a degree that we remove all of the unasked questions that would otherwise make the problem ambiguous. Of course, even the best specification can stumble if you introduce new information. Some of you will have heard of the term ‘frenemy’, which apparently:

can refer to either an enemy pretending to be a friend or someone who really is a friend but is also a rival (from Wikipedia and around since 1953, amazingly!)

What happens if frenemies come into the mix? Well, in either case, we probably want to treat them like an enemy. If they’re an enemy pretending to be a friend, and we know this, then we don’t turn our back on them and, even in academia, it’s never all that wise to turn your back on a rival, either. (Duelling citations at dawn can be messy.) In terms of our simple model, we can deal with extending the model because we clearly understand what the important aspects are of this very simple situation. It would get trickier if frenemies weren’t clearly enemies and we would have to add more rules to our model to deal with this new group.

This can be played out with students of a variety of ages, across a variety of curricula, with materials as simple as a board, a marker and some checkers. Yet this is a powerful way to explain models, specification and improvement, without having to write a single line of actual computer code or talk about mathematics or bridges! I hope you found it useful.

Three Stories: #3 Taking Time for Cats

Posted: January 12, 2014 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, community, education, educational problem, higher education, in the student's head, learning, reflection, storytelling, student perspective, students, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentThere are a number of draft posts sitting on this blog. Posts, which for one reason or another, I’ve either never finished, because the inspiration ran out, or I’ve never published, because I decided not to share them. Most of them were written when I was trying to make sense of being too busy, while at the same time I was taking on more work and feeling bad about not being able to commit properly to everything. I probably won’t ever share many of these posts but I still want to talk about some of the themes.

So, let me tell you a story about cats.

One of the things about cats is that they can be mercurial, creatures of fancy and rapid mood changes. You can spend all day trying to get a cat to sit on your lap and, once you’ve given up and sat back down, 5 minutes later you find a cat on your lap. That’s just the way of cats.

When I was very busy last year, and the year before, I started to see feedback comments from my students that said things like “Nick is great but I feel interrupting him” or I’d try and squeeze them into the 5 minutes I had between other things. Now, students are not cats, but they do have times when they feel they need to come and see you and, sometimes, when that time passes, the opportunity is lost. This isn’t just students, of course, this is people. That’s just the way of people, too. No matter how much you want them to be well organised, predictable and well behaved, sometimes they’re just big, bipedal, mostly hairless cats.

One day, I decided that the best way to make my change my frantic behaviour was to set a small goal, to make me take the time I needed for the surprising opportunities that occurred in a day.

I decided that every time I was walking around the house, even if I was walking out to go to work and thought I was in a hurry, if one of the cats came up to me, I would pay attention to it: scratch it, maybe pick it up, talk to it, and basically interact with the cat.

Over time, of course, what this meant was that I saw more of my cats and I spent more time with them (cats are mercurial but predictable about some things). The funny thing was that the 5 minutes or so I spent doing this made no measurable difference to my day. And making more time for students at work started to have the same effect. Students were happier to drop in to see if I could spend some time with them and were better about making appointments for longer things.

Now, if someone comes to my office and I’m not actually about to rush out, I can spend that small amount of time with them, possibly longer. When I thought I was too busy to see people, I was. When I thought I had time to spend with people, I could.

Yes, this means that I have to be a little more efficient and know when I need to set aside time and do things in a different way, but the rewards are enormous.

I only realised the true benefit of this recently. I flew home from a work trip to Melbourne to discover that my wife and one of our cats, Quincy, were at the Animal Emergency Hospital, because Quincy couldn’t use his back legs. There was a lot of uncertainty about what was wrong and what could be done and, at one point, he stopped eating entirely and it was… not good there for a while.

The one thing that made it even vaguely less awful in that difficult time was that I had absolutely no regrets about the time that we’d spent together over the past 6 months. Every time Quincy had come up to say ‘hello’, I’d stopped to take some time with him. We’d lounged on the couch. He’d napped with me on lazy Sunday afternoons. We had a good bond and, even when the vets were doing things to him, he trusted us and that counted for a lot.

Quincy is now almost 100% and is even more of a softie than before, because we all got even closer while we were looking after him. By spending (probably at most) another five minutes a day, I was able to be happier about some of the more important things in my life and still get my “real” work done.

Fortunately, none of my students are very sick at the moment, but I am pretty confident that I talk to them when they need to (most of the time, there’s still room for improvement) and that they will let me know if things are going badly – with any luck at a point when I can help.

Your time is rarely your own but at least some of it is. Spending it wisely is sometimes not the same thing as spending it carefully. You never actually know when you won’t get the chance again to spend it on something that you value.

Three Stories: #1 What I Learned from Failure

Posted: December 31, 2013 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, blogging, education, educational problem, higher education, in the student's head, learning, reflection, storytelling, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentIt’s considered bad form to start ‘business stories’ with “Once upon a time” but there’s a strong edge of bard to my nature and it’s the end of a long year. (Let’s be generous.) So, are you sitting comfortably? (Ok, I’ll spare you ‘Once…’)

Many years ago, I went to university, after a relatively undistinguished career at school. I got into a course that was not my first preference but, rather than wonder why I had not set the world on fire academically, I assumed that it was because I hadn’t really tried. The companion to this sentiment is that I could achieve whatever I wanted academically, as long as I really wanted it and actually tried. This concept, that I could achieve anything academic I wanted if I tried, got a fairly good workout over the next few years, despite evidence that I was heading in a downward spiral academically. What I became good at was barely avoiding failure, rather than excelling, and while this is a skill, it’s a dangerous line to try and walk. If you’re genuinely aiming to excel, which includes taking the requisite planning steps and time commitment you need, and you fall short then you will probably still do quite well and pass. If you are focused lower down, then missing that bar means failure.

What I didn’t realise at the time was that I was almost doomed to fail when I tried to set my own interpretation of what constituted the right level of effort and participation. If you are a student who has a good knowledge of the whole course then you will have a pretty good idea of how you have answered questions in exams, what is required for assignments and, if you wanted to, you could choose to answer part of a question and have some idea of how many marks are involved. If you don’t know the material in detail, then your perception of your own performance is going to be heavily filtered by your own lack of knowledge. (A reminder of a previous post on this for those who are new here or are vague post-Christmas.)

After some years out in the workforce, and coming back to do postgraduate study, I finally learned something from what should have been quite clear to me, if it hadn’t been hidden by two things: my firm conviction that I could change things immediately if I wished to, and my completely incorrect assumption that my own performance in a subject could be assessed by someone with my level of knowledge!

I became a good student because I finally worked out three key things (with a lot of help and support from my teachers and my friends);

- There is no “lower threshold” of knowledge that allows you to predict if you’re going to pass. If you have enough grasp of the course to know how much you need to do to pass, then you probably know enough to do much better than that! (Terry Pratchett covers this beautifully in a book called “Moving Pictures“, where a student has to know the course better than the teachers to maintain a very specific grade over the years.)

- Telling yourself that you “could have done better” is almost completely useless unless you decide to do better and put a plan in place to achieve that. This excuse gets you off the hook but, unless it’s teamed with remedial action, it’s just an excuse.

- Setting yourself up for failure is just as effective as setting yourself up for success, but it can be far subtler and comprised of many small actions that you don’t take, rather than a few actions that you do take.

Knowing what is going wrong (or thinking you do) doesn’t change anything unless you actively try to change it. It’s a simple truth that, I hope, is a useful and interesting story.

Skill Games versus Money Games: Disguising One Game As Another

Posted: July 5, 2013 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, games, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, plagiarism, principles of design, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design Leave a commentI recently ran across a very interesting article on Gamasutra on the top tips for turning a Free To Play (F2P) game into a Paying game by taking advantage of the way that humans think and act. F2P games are quite common but, obviously, it costs money to make a game so there has to be some sort of associated revenue stream. In some cases, the F2P is a Lite version of the pay version, so after being hooked you go and buy the real thing. Sometimes there is an associated advertising stream, where you viewing the ads earns the producer enough money to cover costs. However, these simple approaches pale into insignificance when compared with the top tips in the link.

Ramin identifies two games for this discussion: games of skill, where it is your ability to make sound decisions that determines the outcome, and money games, where your success is determined by the amount of money you can spend. Games of chance aren’t covered here but, given that we’re talking about motivation and agency, we’re depending upon one specific blindspot (the inability of humans to deal sensibly with probability) rather than the range of issues identified in the article.

I dont want to rehash the entire article but the key points that I want to discuss are the notion of manipulating difficulty and fun pain. A game of skill is effectively fun until it becomes too hard. If you want people to keep playing then you have to juggle the difficulty enough to make it challenging but not so hard that you stop playing. Even where you pay for a game up front, a single payment to play, you still want to get enough value out of it – too easy and you finish too quickly and feel that you’ve wasted your money; too hard and you give up in disgust, again convinced that you’ve wasted your money. Ultimately, in a pure game of skill, difficulty manipulation must be carefully considered. As the difficulty ramps up, the player is made uncomfortable, the delightful term fun pain is applied here, and resolving the difficulty removes this.

Or, you can just pay to make the problem go away. Suddenly your game of skill has two possible modes of resolution: play through increasing difficulty, at some level of discomfort or personal inconvenience, or, when things get hard enough, pump in a deceptively small amount of money to remove the obstacle. The secret of the P2P game that becomes successfully monetised is that it was always about the money in the first place and the initial rounds of the game were just enough to get you engaged to a point where you now have to pay in order to go further.

You can probably see where I’m going with this. While it would be trite to describe education as a game of skill, it is most definitely the most apt of the different games on offer. Progress in your studies should be a reflection of invested time in study, application and the time spent in developing ideas: not based on being ‘lucky’, so the random game isn’t a choice. The entire notion of public education is founded on the principle that educational opportunities are open to all. So why do some parts of this ‘game’ feel like we’ve snuck in some covert monetisation?

I’m not talking about fees, here, because that’s holding the place of the fee you pay to buy a game in the first place. You all pay the same fee and you then get the same opportunities – in theory, what comes out is based on what the student then puts in as the only variable.

But what about textbooks? Unless the fee we charge automatically, and unavoidably, includes the cost of the textbook, we have now broken the game into two pieces: the entry fee and an ‘upgrade’. What about photocopying costs? Field trips? A laptop computer? An iPad? Home internet? Bus fare?

It would be disingenuous to place all of this at the feet of public education – it’s not actually the fault of Universities that financial disparity exists in the world. It is, however, food for thought about those things that we could put into our courses that are useful to our students and provide a paid alternative to allow improvement and progress in our courses. If someone with the textbook is better off than someone without the textbook, because we don’t provide a valid free alternative, then we have provided two-tiered difficulty. This is not the fun pain of playing a game, we are now talking about genuine student stress, a two-speed system and a very high risk that stressed students will disengage and leave.

From my earlier discussions on plagiarism, we can easily tie in Ramin’s notion of the driver of reward removal, where players have made so much progress that, on facing defeat, they will pay a fee to reduce the impact of failure; or, in some cases, to remove it completely. As Ramin notes:

“This technique alone is effective enough to make consumers of any developmental level spend.”

It’s not just lost time people are trying to get back, it’s the things that have been achieved in that time. Combine that with, in our case, the future employability and perception of that piece of paper, and we have a very strong behavioural driver. A number of the tricks Ramin describes don’t work as well on mature and aware thinkers but this one is pretty reliable. If it’s enough to make people pay money, regardless of their development level, then there are lots of good design decisions we can make from this – lower risk assessment, more checkpointing, steady progress towards achievement. We know lots of good ways to avoid this, if we consider it to be a problem and want to take the time to design around it.

This is one of the greatest lessons I’ve learned about studying behaviour, even as a rank amateur. Observing what people do and trying to build systems that will work despite that makes a lot more sense than building a system that works to some ideal and trying to jam people into it. The linked article shows us how people are making really big piles of money by knowing how people work. It’s worth looking at to make sure that we aren’t, accidentally, manipulating students in the same way.

The defining question.

Posted: July 2, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, community, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, workload Leave a commentThere has been a lot going on for me recently. A lot of thinking, a lot of work and an amount of getting involved in things because my students trust me and will come to me to ask questions, which sometimes puts me in the uncomfortable position of having to juggle my accommodation for the different approaches of my colleagues and my own beliefs, as well as acting in everyone’s best interests. I’m not going to go into details but I think that I can summarise my position on everything, as an educator, by phrasing it in one question.

Is this course of action to the student’s benefit?

I mean, that’s it, isn’t it? If the job is educating students and developing the citizens of tomorrow, then everything that we do should be to the benefit of the student and/or future graduate. But it’s never simple, is it, because the utilitarian calculus to derive benefit quickly becomes complicated when we consider the effect of institutional reputation or perception on the future benefit to the student. But maybe that’s over thinking things (gasp, I hear regular readers cry). I’m not sure I know how to guide student behaviour to raise my University’s ranking in various measures – but I do know how to guide student behaviour to reduce the number of silly or thoughtless things they do, to enhance their learning and to help them engage. Maybe the simple question is the best? Will the actions I take today improve my students’ knowledge or enhance their capacity to learn? Have I avoided wasting their time doing something that we do because we have always done it, rather than giving them something to do because it is what we should be doing? Am I always considering the benefit to the largest group of students, while considering the needs of the individual?

Every time I see a system that has a fixed measure of success, people optimise for it. If it’s maximum profit, people maximise profit. If it’s minimum space, people cut their space. Guidelines help a lot in working out which course of action to take: when faced with a choice between A and B, choose the option that maximises your objective. This even works without a strong vision of the future, which is good because I’m not sure we have a clear enough view of the long path to graduation to really be specific about this. There is always a risk that people will get the assessment of benefit wrong, which can lead to soft marking or lax standards, but I’m not a believer that post hoc harshness is the solution to inherited laxity from another system (especially where that may be a perception that’s not grounded in reality). Looking at all of my actions in terms of a real benefit, to the student, to their community, to our equality standards, to our society – that shines a bright light on what we do so we can clearly see what we’re doing and, if it requires change, illuminates the path to change.

Let’s not turn “Chalk and Talk” into “Watch and Scratch”

Posted: July 1, 2013 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, higher education, moocs, principles of design, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, tools, universal principles of design 1 CommentWe are now starting to get some real data on what happens when people “take” a MOOC (via Mark’s blog). You’ll note the scare quotes around the word “take”, because I’m not sure that we have really managed to work out what it means to get involved in a course that is offered through the MOOC mechanism. Or, to be more precise, some people think they have but not everyone necessarily agrees with them. I’m going to list some of my major concerns, even in the face of the new clickstream data, and explain why we don’t have a clear view of the true value/approaches for MOOCs yet.

- On-line resources are not on-line courses and people aren’t clear on the importance of an overall educational design and facilitation mechanism. Many people have mused on this in the past. If all the average human needed was a set of resources and no framing or assistive pedagogy then our educational resources would be libraries and there would be no teachers. While there are a number of offerings that are actually courses, applying the results of the MIT 6.002x to what are, for the most part, unstructured on-line libraries of lecture recordings is not appropriate. (I’m not even going to get into the cMOOC/xMOOC distinction at this point.) I suspect that this is just part of the general undervaluing of good educational design that rears its head periodically.

- Replacing lectures with on-line lectures doesn’t magically improve things. The problem with “chalk and talk”, where it is purely one-way with no class interaction, is that we know that it is not an effective way to transfer knowledge. Reading the textbook at someone and forcing them to slowly transcribe it turns your classroom into an inefficient, flesh-based photocopier. Recording yourself standing in front a class doesn’t automatically change things. Yes, your students can time shift you, both to a more convenient time and at a more convenient speed, but what are you adding to the content? How are you involving the student? How can the student benefit from having you there? When we just record lectures and put them up there, then unless they are part of a greater learning design, the student is now sitting in an isolated space, away from other people, watching you talk, and potentially scratching their head while being unable to ask you or anyone else a question. Turning “chalk and talk” into “watch and scratch” is not an improvement. Yes, it scales so that millions of people can now scratch their heads in unison but scaling isn’t everything and, in particular, if we waste time on an activity under the illusion that it will improve things, we’ve gone backwards in terms of quality for effort.

- We have yet to establish the baselines for our measurement. This is really important. An on-line system us capable of being very heavily tracked and it’s not just links. The clickstream measurements in the original report record what people clicked on as they worked with the material. But we can only measure that which is set up for measurement – so it’s quite hard to compare the activity in this course to other activities that don’t use technology. But there are two subordinate problems to this (and I apologise to physicists for the looseness of the following) :

- Heisenberg’s MOOC: At the quantum scale, you can either tell where something is or what it is doing – the act of observation has limits of precision. Borrowing that for the macro scale: measure someone enough and you’ll see how they behave under measurement but the measurements we pick tend to fall into the stage they’ve reached or the actions they’ve taken. It’s very complex to combine quantitative and qualitative measures to be able to map someone’s stage and their comprehension/intentions/trajectory. You don’t have to accept arguments based on the Hawthorne Effect to understand why this does not necessarily tell you much about unobserved people. There are a large number of people taking these courses out of curiosity, some of whom already have appropriate qualifications, with only 27% the type of student that you would expect to see at this level of University. Combine that with a large number of researchers and curious academics who are inspecting each other’s courses, I know of at least 12 people in my own University taking MOOCs of various kinds to see what they’re like, and we have the problem that we are measuring people who are merely coming in to have a look around and are probably not as interested in the actual course. Until we can actually shift MOOC demography to match that of our real students, we are always going to have our measurements affected by these observers. The observers might not mind being heavily monitored and observed, but real students might. Either way, numbers are not the real answer here – they show us what but there is still too much uncertainty in the why and the how.

- Schrödinger’s MOOC: Oh, that poor reductio ad absurdum cat. Does the nature of the observer change the behaviour of the MOOC and force it to resolve one way or another (successful/unsuccessful)? If so, how and when? Does the fact of observation change the course even more than just in enrolments and uncertainty of validity of figures? The clickstream data tells us that the forums are overwhelmingly important to students, with 90% of people who viewed threads without commenting, and only 3% of total students enrolled every actually posted anything in a thread. What was the make-up of that 3% and was it actual students or the over-qualified observers who then provided an environment that 90% of their peers found useful?

- Numbers need context and unasked questions give us no data: As one example, the authors of the study were puzzled that so few people had logged in from China, which surprised them. Anyone who has anything to do with network measurement is going to be aware that China is almost always an outlier in network terms. My blog, for example, has readers from around the world – but not China. It’s also important to remember that any number of Chinese network users will VPN/SSH to hosts outside China to enjoy unrestricted search and network access. There may have been many Chinese people (who didn’t self-identify for obvious reasons) who were using proxies from outside China. The numbers on this particular part of the study do not make sense unless they are correctly contextualised. We also see a lack of context in the reporting on why people were doing the course – the numbers for why people were doing it had to be augmented from comments in the forum that people ‘wanted to see if they could make it through an MIT course’. Why wasn’t that available from the initial questions?

- We don’t know what pass/fail is going to look like in this environment. I can’t base any MOOC plans of my own on how people respond to a MIT-branded course but it is important to note that MIT’s approach was far more than “watch and scratch”, as is reflected by their educational design in providing various forms of materials, discussions forums, homework and labs. But still, 155,000 people signed up for this and only 7,000 received certificates. 2/3 of people who registered then went on to do nothing. I don’t think that we can treat a success rate of less than 5% as a success rate. Even where we say that 2/3 dropped out, this still equates to a pass rate under 14%. Is that good? Is that bad? Taking everything into account from above, my answer is “We don’t know.” If we get 17% next time, is that good or bad? How do we make this better?

- The drivers are often wrong. Several US universities have gone on the record to complain about undermining their colleagues and have refused to take part in MOOC-related activities. The reasons for this vary but the greatest fear is that MOOCs will be used to reduce costs by replacing existing lecturing staff with a far smaller group and using MOOCs to handle the delivery. From a financial argument, MOOCs are astounding – 155,000 people contacted for the cost of a few lecturers. Contrast that with me teaching a course to 100 students. If we look at it from a quality perspective, and dealing with all of the points so far, we have no argument to say that MOOCs are as good as our good teaching – but we do know that they are easily as good as our bad teaching. But from a financial perspective? MOOC is king. That is, however, not how we guarantee educational quality. Of course, when we scale, we can maintain quality by increasing resources but this runs counter to a cost-saving argument so we’re almost automatically being prevented from doing what is required to make the large scale course work by the same cost driver that led to its production in the first place!

- There are a lot of statements but perhaps not enough discussion. These are trying times for higher education and everyone wants an edge, more students, higher rankings, to keep their colleagues and friends in work and, overall, to do the right thing for their students. Senior management, large companies, people worried about money – they’re all talking about MOOCs as if they are an accepted substitute for traditional approaches – at the same time as we are in deep discussion about which of the actual traditional approaches are worthwhile and which new approaches are going to work better. It’s a confusing time as we try to handle large-scale adoption of blended learning techniques at the same time people are trying to push this to the large scale.

I’m worried that I seem to be spending most of my time explaining what MOOCs are to people who are asking me why I’m not using a MOOC. I’m even more worried when I am still yet to see any strong evidence that MOOCs are going to provide anything approaching the educational design and integrity that has been building for the past 30 years. I’m positively terrified when I see corporate providers taking over University delivery before we have established actual measurable quality and performance guidelines for this incredibly important activity. I’m also bothered by statements found at the end of the study, which was given prominence as a pull quote:

[The students] do not follow the norms and rules that have governed university courses for centuries nor do they need to.

I really worry about this because I haven’t yet seen any solid evidence that this is true, yet this is exactly the kind of catchy quote that is going to be used on any number of documents that will come across my desk asking me when I’m going to MOOCify my course, rather than discussing if and why and how we will make a transition to on-line blended learning on the massive scale. The measure of MOOC success is not the number of enrolees, nor is it the number of certificates awarded, nor is it the breadth of people who sign up. MOOCs will be successful once we have worked out how to use this incredibly high potential approach to teaching to deliver education at a suitably high level of quality to as many people as possible, at a reduced or even near-zero cost. The potential is enormous but, right now, so is the risk!

Another semester, more lessons learned (mostly by me).

Posted: June 16, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, plagiarism, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design Leave a commentI’ve just finished the lecturing component for my first year course on programming, algorithms and data structures. As always, the learning has been mutual. I’ve got some longer posts to write on this at some time in the future but the biggest change for this year was dropping the written examination component down and bringing in supervised practical examinations in programming and code reading. This has given us some interesting results that we look forward to going through, once all of the exams are done and the marks are locked down sometime in late July.

Whenever I put in practical examinations, we encounter the strange phenomenon of students who can mysteriously write code in very short periods of time in a practical situation very similar to the practical examination, but suddenly lose the ability to write good code when they are isolated from the Internet, e-Mail and other people’s code repositories. This is, thank goodness, not a large group (seriously, it’s shrinking the more I put prac exams in) but it does illustrate why we do it. If someone has a genuine problem with exam pressure, and it does occur, then of course we set things up so that they have more time and a different environment, as we support all of our students with special circumstances. But to be fair to everyone, and because this can be confronting, we pitch the problems at a level where early achievement is possible and they are also usually simpler versions of the types of programs that have already been set as assignment work. I’m not trying to trip people up, here, I’m trying to develop the understanding that it’s not the marks for their programming assignments that are important, it’s the development of the skills.

I need those people who have not done their own work to realise that it probably didn’t lead to a good level of understanding or the ability to apply the skill as you would in the workforce. However, I need to do so in a way that isn’t unfair, so there’s a lot of careful learning design that goes in, even to the selection of how much each component is worth. The reminder that you should be doing your own work is not high stakes – 5-10% of the final mark at most – and builds up to a larger practical examination component, worth 30%, that comes after a total of nine practical programming assignments and a previous prac exam. This year, I’m happy with the marks design because it takes fairly consistent failure to drop a student to the point where they are no longer eligible for redemption through additional work. The scope for achievement is across knowledge of course materials (on-line quizzes, in-class scratchy card quizzes and the written exam), programming with reference materials (programming assignments over 12 weeks), programming under more restricted conditions (the prac exams) and even group formation and open problem handling (with a team-based report on the use of queues in the real world). To pass, a student needs to do enough in all of these. To excel, they have to have a good broad grasp of theoretical and practical. This is what I’ve been heading towards for this first-year course, a course that I am confident turns out students who are programmers and have enough knowledge of core computer science. Yes, students can (and will) fail – but only if they really don’t do enough in more than one of the target areas and then don’t focus on that to improve their results. I will fail anyone who doesn’t meet the standard but I have no wish to do any more of that than I need to. If people can come up to standard in the time and resource constraints we have, then they should pass. The trick is holding the standard at the right level while you bring up the people – and that takes a lot of help from my colleagues, my mentors and from me constantly learning from my students and being open to changing the learning design until we get it right.

Of course, there is always room for improvement, which means that the course goes back up on blocks while I analyse it. Again. Is this the best way to teach this course? Well, of course, what we will do now is to look at results across the course. We’ll track Prac Exam performance across all practicals, across the two different types of quizzes, across the reports and across the final written exam. We’ll go back into detail on the written answers to the code reading question to see if there’s a match for articulation and comprehension. We’ll assess the quality of response to the exam, as well as the final marked outcome, to tie this back to developmental level, if possible. We’ll look at previous results, entry points, pre-University marks…

And then we’ll teach it again!

Why You Won’t Finish This Post

Posted: June 10, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, design, education, educational problem, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, universal principles of design 3 CommentsA friend of mine on Facebook posted a link to a Slate article entitled “You Won’t Finish This Article: Why people online don’t read to the end” and it’s told me everything that I’ve been doing wrong with this blog for about the last 410 hours. Now, this doesn’t even take into account that, by linking to something potentially more interesting on a well-known site, I’ve now buried the bottom of this blog post altogether because a number of you will follow the link and, despite me asking it to appear in a new window, you will never come back to this article. (This has quite obvious implications for the teaching materials we put up, so it’s well worth a look.)

Now, on the off-chance that you did come back (hi!), we have to assume that you didn’t read all of the linked article (if you read any at all) because 28% of you ‘bounced’ immediately and didn’t actually read much at all of that page – you certainly didn’t scroll. Almost none of you read to the bottom. What is, however, amusing is that a number of you will have either Liked or forwarded a link to one or both of these pages – never having stepped through or scrolled once, but because the concept at the start looks cool. Of course, according the Slate analysis, I’ve lost over half my readers by now. Of course, this does assume the Slate layout, where an image breaks things up and forces people to scroll through. So here’s an image that will discourage almost everyone from continuing. However, it is a pretty picture:

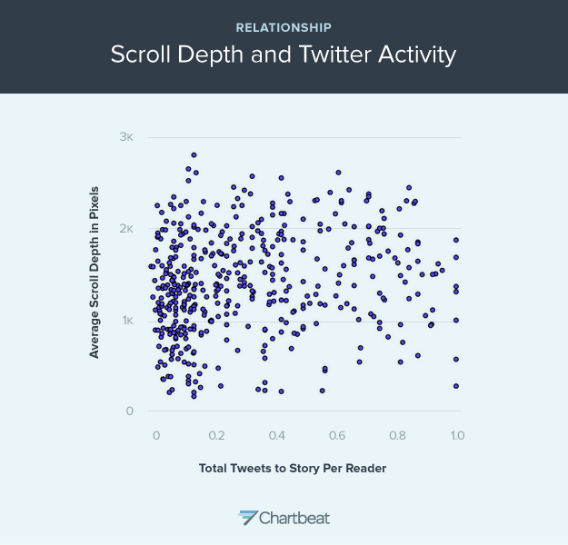

This graph shows the relationship between scroll depth and Tweet (From Slate and courtesy of Chartbeat)

What it says is that there is not an enormously strong correlation between depth of reading and frequency of tweet. So, the amount that a story is read doesn’t really tell you how much people will want to (or actually) share it. Overall, the Slate article makes it fairly clear that unless I manage to make my point in the first paragraph, I have little chance of being read any further – but if I make that first paragraph (or first images) appealing enough, any number of people will like and share it.

Of course, if people read down this far (thanks!) then they will know that I secretly start advocating the most horrible things known to humanity so, when someone finally follows their link and miraculously reads down this far, survives the Slate link out, and doesn’t end up mired in the picture swamp above, they will discover…

Oh, who am I kidding. I’ll just come back and fill this in later.

(Having stolen a time machine, I can now point out that this is yet another illustration of why we need to be thoughtful about what our students are going to do in response to on-line and hyperlinked materials rather than what we would like them to do. Any system that requires a better human, or a human to act in a way that goes against all the evidence we have of their behaviour, requires modification.)

Note to Self

Posted: May 19, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, community, education, educational problem, ethics, higher education, in the student's head, learning, marcus aurelius, meditations, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking 3 CommentsI’ve mentioned the “Meditations” of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius before – I’ve been writing this blog for over 450 hours, I’m not sure there’s anything I haven’t mentioned except my feelings on the season finale of Doctor Who, Series 7. (Eh.) Marcus Aurelius, philosopher, statesman, Roman, and Emperor wrote twelve “books” which were apparently never meant to be published. These are the private musings, notes to self, of a thoughtful man, written stoically and Stoically. When he lectures anyone, he lectures himself. He even poses questions to parts of himself: his soul, most notably.

There is much to admire in the simplicity and purpose of Marcus Aurelius’ thoughts. They are brief, because Emperors are busy people, especially when earning titles such as Germanicus (which usually involves squashing a nation state or two). They are direct, because he is talking to himself and he needs to be honest. He repeats himself for emphasis and to indicate importance, not out of forgetfulness.

Best, he writes for himself, for clarity, for the now and without thinking of a future audience.

There is a great deal to think about in this, because if you have read “Meditations”, you will know that every page contains a gem and some pages have jewels cascading from them. Yet these are the private thoughts of a person recording ways to improve himself and to keep himself in check – while he managed the Roman empire.

When I talk about improvement, I’m always trying to improve myself. When I find fault, I’ve usually found it in myself first. Yet, what a lot of words I write! Perhaps it is time to reinvestigate brevity, directness and a generosity towards the self that translates well into a kindness to strangers who might stumble upon this. The last thing I’d want to do is to stop people finding what zircons there are because the preamble is too demanding or the journey to the point too long.

Once again, I give my thanks to the writings of someone who died 2000 years ago and gave me so much to think about. Vale, Marcus Aurelius.