On being the right choice.

Posted: March 29, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, Clarion West, community, education, ethics, first choice, higher education, in the student's head, learning, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, work/life balance Leave a commentI write fiction in my (increasing amounts of) free time and I submit my short stories to a variety of magazines, all of whom have rejected me recently. I also applied to take part in a six-week writing workshop called Clarion West this year, because this year’s instructors were too good not to apply! I also got turned down for Clarion West.

Only one of these actually stung and it was the one where, rather than thinking hey, that story wasn’t right for that venue, I had to accept that my writing hadn’t been up to the level of the 16 very talented writers who did get in. I’m an academic so being rejected from conferences is part of my job (as is being told that I’m wrong and, occasionally, told that I’m right but in a way that makes it sounds like I stumbled over it.)

And there is a difference because one of these is about the story itself and the other is about my writing, although many will recognise that this is a tenuous and artificial separation, probably to keep my self-image up. But this is a setback and I haven’t written much (anything) since the last rejection but that’s ok, I’ll start writing again and I’ll work on it and, maybe, one day I’ll get something published and people will like it and that will be that dealt with.

It always stings, at least a little, to be runner-up or not selected when you had your heart set on something. But it’s interesting how poisonous it can be to you and the people around you when you try and push through a situation where you are not the first choice, yet you end up with the role anyway.

For the next few paragraphs, I’m talking about selecting what to do, assuming that you have the choice and freedom to make that choice. For those who are struggling to stay alive, choice is often not an option. I understand that, so please read on knowing that I’m talking about making the best of the situations where your own choices can be used against you.

There’s a position going at my Uni, it doesn’t matter what, and I was really quite interested in it, although I knew that people were really looking around outside the Uni for someone to fill it. It’s been a while and it hasn’t been filled so, when the opportunity came up, I asked about it and noted my interest.

But then, I got a follow-up e-mail which said that their first priority was still an external candidate and that they were pushing out the application period even further to try and do that.

Now, here’s the thing. This means that they don’t want me to do it and, so you know, that is absolutely fine with me. I know what I can do and I’m very happy with that but I’m not someone with a lot of external Uni experience. (Soldier, winemaker, sysadmin, international man of mystery? Yes. Other Unis? Not a great deal.) So I thanked them for the info, wished them luck and withdrew my interest. I really want them to find someone good, and quickly, but they know what they want and I don’t want to hang around, to be kicked into action when no-one better comes along.

I’m good enough at what I do to be a first choice and I need to remember that. All the time.

It’s really important to realise when you’d be doing a job where you and the person who appoints you know that you are “second-best”. You’re only in the position because they couldn’t find who they wanted. It’s corrosive to the spirit and it can produce a treacherous working relationship if you are the person that was “settled” on. The role was defined for a certain someone – that’s what the person in charge wants and that is what they are going to be thinking the whole time someone is in that role. How can you measure up to the standards of a better person who is never around to make mistakes? How much will that wear you down as a person?

As academics, and for many professional, there are so many things that we can do, that it doesn’t make much sense to take second-hand opportunities, after the A players have chosen not to show up. If you’re doing your job well and you go for something where that’s relevant, you should be someone’s first choice, or you should be in the first sweep. If not, then it’s not something that they actually need you for. You need to save your time and resources for those things where people actually want you – not a warm body that you sort of approximate. You’re not at the top level yet? Then it’s something to aim for but you won’t be able to do the best projects and undertake the best tasks to get you into that position, if you’re always standing in and doing the clean-up work because you’re “always there”.

I love my friends and family because they don’t want a Nick-ish person in their life, they want me. When I’m up, when I’m down, when I’m on, when I’m off – they want me. And that’s the way to bolster a strong self-image and make sure that you understand how important you can be.

If you keep doing stuff where you could be anyone, you won’t have the time to find, pursue or accept those things that really need you and this is going to wear away at you. Years ago, I stopped responding when someone sent out an e-mail that said “Can anyone do this?” because I was always one of the people who responded but this never turned into specific requests to me. Since I stopped doing it, people have to contact me and they value me far more realistically because of it.

I don’t believe I’m on the Clarion West reserve list (no doubt they would have told me), which is great because I wouldn’t go now. If my writing wasn’t good enough then, someone getting sick doesn’t magically make my writing better and, in the back of my head and in the back of the readers’, we’ll all know that I’m not up to standard. And I know enough about cognitive biases to know that it would get in the way of the whole exercise.

Never give up anything out of pique, especially where it’s not your essence that is being evaluated, but feel free to politely say No to things where they’ve made it clear that they don’t really want you but they’re comfortable with settling.

If you’re doing things well, no-one should be settling for you – you should always be in that first choice.

Anything else? It will drive you crazy and wear away your soul. Trust me on this.

Teleportation and the Student: Impossibility As A Lesson Plan

Posted: March 7, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, design, education, higher education, human body, in the student's head, learning, lossy compression, science fiction, Sean WIlliams, Star Trek, students, teaching, teaching approaches, teleportation, teleporters, thinking, tools Leave a comment

Tricking a crew-mate into looking at their shoe during a transport was a common prank in the 23rd Century.

Teleporters, in one form or another, have been around in Science Fiction for a while now. Most people’s introduction was probably via one of the Star Treks (the transporter) which is amusing, as it was a cost-cutting mechanism to make it easy to get from one point in the script to another. Is teleportation actually possible at the human scale? Sadly, the answer is probably not although we can do some cool stuff at the very, very small scale. (You can read about the issues in teleportation here and here, an actual USAF study.) But just because something isn’t possible doesn’t mean that we can’t get some interesting use out of it. I’m going to talk through several ways that I could use teleportation to drive discussion and understanding in a computing course but a lot of this can be used in lots of places. I’ve taken a lot of shortcuts here and used some very high level analogies – but you get the idea.

- Data Transfer

The first thing to realise is that the number of atoms in the human body is huge (one octillion, 1E27, roughly, which is one million million million million million) but the amount of information stored in the human body is much, much larger than that again. If we wanted to get everything, we’re looking at transferring quattuordecillion bits (1E45), and that’s about a million million million times the number of atoms in the body. All of this, however, ignores the state of all the bacteria and associated hosted entities that live in the human body and the fact that the number of neural connections in the brain appears to be larger than we think. There are roughly 9 non-human cells associated with your body (bacteria et al) for every cell.

Put simply, the easiest way to get the information in a human body to move around is to leave it in a human body. But this has always been true of networks! In the early days, it was more efficient to mail a CD than to use the (at the time) slow download speeds of the Internet and home connections. (Actually, it still is easier to give someone a CD because you’ve just transferred 700MB in one second – that’s 5.6 Gb/s and is just faster than any network you are likely to have in your house now.)

Right now, the fastest network in the world clocks in at 255 Tbps and that’s 255,000,000,000,000 bits in a second. (Notice that’s over a fixed physical optical fibre, not through the air, we’ll get to that.) So to send that quattuordecillion bits, it would take (quickly dividing 1E45 by 255E12) oh…

about 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000

years. Um.

- Information Redundancy and Compression

The good news is that we probably don’t have to send all of that information because, apart from anything else, it appears that a large amount of human DNA doesn’t seem to do very much and there’s lot of repeated information. Because we also know that humans have similar chromosomes and things lie that, we can probably compress a lot of this information and send a compressed version of the information.

The problem is that compression takes time and we have to compress things in the right way. Sadly, human DNA by itself doesn’t compress well as a string of “GATTACAGAGA”, for reasons I won’t go into but you can look here if you like. So we have to try and send a shortcut that means “Use this chromosome here” but then, we have to send a lot of things like “where is this thing and where should it be” so we’re still sending a lot.

There are also two types of compression: lossless (where we want to keep everything) and lossy (where we lose bits and we will lose more on each regeneration). You can work out if it’s worth doing by looking at the smallest number of bits to encode what you’re after. If you’ve ever seen a really bad Internet image with strange lines around the high contrast bits, you’re seeing lossy compression artefacts. You probably don’t want that in your genome. However, the amount of compression you do depends on the size of the thing you’re trying to compress so now you have to work out if the time to transmit everything is still worse than the time taken to compress things and then send the shorter version.

So let’s be generous and say that we can get, through amazing compression tricks, some sort of human pattern to build upon and the like, our transferred data requirement down to the number of atoms in the body – 1E27. That’s only going to take…

124,267

years. Um, again. Let’s assume that we want to be able to do this in at most 60 minutes to do the transfer. Using the fastest network in the world right now, we’re going to have get our data footprint down to 900,000,000,000,000,000 bits. Whew, that’s some serious compression and, even on computers that probably won’t be ready until 2018, it would have taken about 3 million million million years to do the compression. But let’s ignore that. Because now our real problems are starting…

- Signals Ain’t Simple and Networks Ain’t Wires.

In earlier days of the telephone, the movement of the diaphragm in the mouthpiece generated electricity that was sent down the wires, amplified along the way, and then finally used to make movement in the earpiece that you interpreted as sound. Changes in the electric values weren’t limited to strict values of on or off and, when the signal got interfered with, all sorts of weird things happen. Remember analog television and all those shadows, snow and fuzzy images? Digital encoding takes the measurements of the analog world and turns it into a set of 0s and 1s. You send 0s and 1s (binary) and this is turned back into something recognisable (or used appropriately) at the other end. So now we get amazingly clear television until too much of the signal is lost and then we get nothing. But, up until then, progress!

But we don’t send giant long streams across a long set of wires, we send information in small packets that contain some data, some information on where to send it and it goes through an array of active electronic devices that take your message from one place to another. The problem is that those packet headers add overhead, just like trying to mail a book with individual pages in addressed envelopes in the postal service would. It takes time to get something onto the network and it also adds more bits! Argh! More bits! But it can’t get any worse can it?

- Networks Aren’t Perfectly Reliable

If you’ve ever had variable performance on your home WiFi, you’ll understand that transmitting things over the air isn’t 100% reliable. There are two things that we have to thing about in terms of getting stuff through the network: flow control (where we stop our machine from talking to other things too quickly) and congestion control (where we try to manage the limited network resources so that everyone gets a share). We’ve already got all of these packets that should be able to be directed to the right location but, well, things can get mangled in transmission (especially over the air) and sometimes things have to be thrown away because the network is so congested that packets get dropped to try and keep overall network throughput up. (Interference and absorption is possible even if we don’t use wireless technology.)

Oh, no. It’s yet more data to send. And what’s worse is that a loss close to the destination will require you to send all of that information from your end again. Suddenly that Earth-Mars teleporter isn’t looking like such a great idea, is it, what with the 8-16 minute delay every time a cosmic ray interferes with your network transmission in space. And if you’re trying to send from a wireless terminal in a city? Forget it – the WiFi network is so saturated in many built-up areas that your error rates are going to be huge. For a web page, eh, it will take a while. For a Skype call, it will get choppy. For a human information sequence… not good enough.

Could this get any worse?

- The Square Dance of Ordering and Re-ordering

Well, yes. Sometimes things don’t just get lost but they show up at weird times and in weird orders. Now, for some things, like a web page, this doesn’t matter because your computer can wait until it gets all of the information and then show you the page. But, for telephone calls, it does matter because losing a second of call from a minute ago won’t make any sense if it shows up now and you’re trying to keep it real time.

For teleporters there’s a weird problem in that you have to start asking questions like “how much of a human is contained in that packet”? Do you actually want to have the possibility of duplicate messages in the network or have you accidentally created extra humans? Without duplication possibilities, your error recovery rate will plummet, unless you build in a lot more error correction, which adds computation time and, sorry, increases the number of bits to send yet again. This is a core consideration of any distributed system, where we have to think about how many copies of something we need to send to ensure that we get one – or whether we care if we have more than one.

PLEASE LET THERE BE NO MORE!

- Oh, You Wanted Security, Integrity and Authenticity, Did You?

I’m not sure I’d want people reading my genome or mind state as it traversed across the Internet and, while we could pretend that we have a super-secret private network, security through obscurity (hiding our network or data) really doesn’t work. So, sorry to say, we’re going to have to encrypt our data to make sure that no-one else can read it but we also have to carry out integrity tests to make sure that what we sent is what we thought we sent – we don’t want to send a NICK packet and end up with a MICE packet, for simplistic example. And this is going to have to be sent down the same network as before so we’re putting more data bits down that poor beleaguered network.

Oh, and did I mention that encryption will also cost you more computational overhead? Not to mention the question of how we undertake this security because we have a basic requirement to protect all of this biodata in our system forever and eliminate the ability that someone could ever reproduce a copy of the data – because that would produce another person. (Ignore the fact that storing this much data is crazy, anyway, and that the current world networks couldn’t hold it all.)

And who holds the keys to the kingdom anyway? Lenovo recently compromised a whole heap of machines (the Superfish debacle) by putting what’s called a “self-signed root certificate” on their machines to allow an adware partner to insert ads into your viewing. This is the equivalent of selling you a house with a secret door that you don’t know about it that has a four-digit pin lock on it – it’s not secure and because you don’t know about it, you can’t fix it. Every person who worked for the teleporter company would have to be treated as a hostile entity because the value of a secretly tele-cloned person is potentially immense: from the point of view of slavery, organ harvesting, blackmail, stalking and forced labour…

But governments can get in the way, too. For example, the FREAK security flaw is a hangover from 90’s security paranoia that has never been fixed. Will governments demand in-transit inspection of certain travellers or the removal of contraband encoded elements prior to materialisation? How do you patch a hole that might have secretly removed essential proteins from the livers of every consular official of a particular country?

The security protocols and approach required for a teleporter culture could define an entire freshman seminar in maths and CS and you could still never quite have scratched the surface. But we are now wandering into the most complex areas of all.

- Ethics and Philosophy

How do we define what it means to be human? Is it the information associated with our physical state (locations, spin states and energy levels) or do we have to duplicate all of the atoms? If we can produce two different copies of the same person, the dreaded transporter accident, what does this say about the human soul? Which one is real?

How do we deal with lost packets? Are they a person? What state do they have? To whom do they belong? If we transmit to a site that is destroyed just after materialisation, can we then transmit to a safe site to restore the person or is that on shaky ground?

Do we need to develop special programming languages that make it impossible to carry out actions that would violate certain ethical or established protocols? How do we sign off on code for this? How do we test it?

Do we grant full ethical and citizenship rights to people who have been through transporters, when they are very much no longer natural born people? Does country of birth make any sense when you are recreated in the atoms of another place? Can you copy yourself legitimately? How much of yourself has to survive in order for it to claim to be you? If someone is bifurcated and ends up, barely alive, with half in one place and half in another …

There are many excellent Science Fiction works referenced in the early links and many more out there, although people are backing away from it in harder SF because it does appear to be basically impossible. But if a networking student could understand all of the issues that I’ve raised here and discuss solutions in detail, they’d basically have passed my course. And all by discussing an impossible thing.

With thanks to Sean Williams, Adelaide author, who has been discussing this a lot as he writes about teleportation from the SF perspective and inspired this post.

Why “#thedress” is the perfect perception tester.

Posted: March 2, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, Avant garde, collaboration, community, Dada, data visualisation, design, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, Kazimir Malevich, learning, Marcel Duchamp, modern art, principles of design, readymades, reflection, resources, Russia, Stalin, student perspective, Suprematism, teaching, thedress, thinking 1 CommentI know, you’re all over the dress. You’ve moved on to (checks Twitter) “#HouseOfCards”, Boris Nemtsov and the new Samsung gadgets. I wanted to touch on some of the things I mentioned in yesterday’s post and why that dress picture was so useful.

The first reason is that issues of conflict caused by different perception are not new. You only have to look at the furore surrounding the introduction of Impressionism, the scandal of the colour palette of the Fauvists, the outrage over Marcel Duchamp’s readymades and Dada in general, to see that art is an area that is constantly generating debate and argument over what is, and what is not, art. One of the biggest changes has been the move away from representative art to abstract art, mainly because we are no longer capable of making the simple objective comparison of “that painting looks like the thing that it’s a painting of.” (Let’s not even start on the ongoing linguistic violence over ending sentences with prepositions.)

Once we move art into the abstract, suddenly we are asking a question beyond “does it look like something?” and move into the realm of “does it remind us of something?”, “does it make us feel something?” and “does it make us think about the original object in a different way?” You don’t have to go all the way to using body fluids and live otters in performance pieces to start running into the refrains so often heard in art galleries: “I don’t get it”, “I could have done that”, “It’s all a con”, “It doesn’t look like anything” and “I don’t like it.”

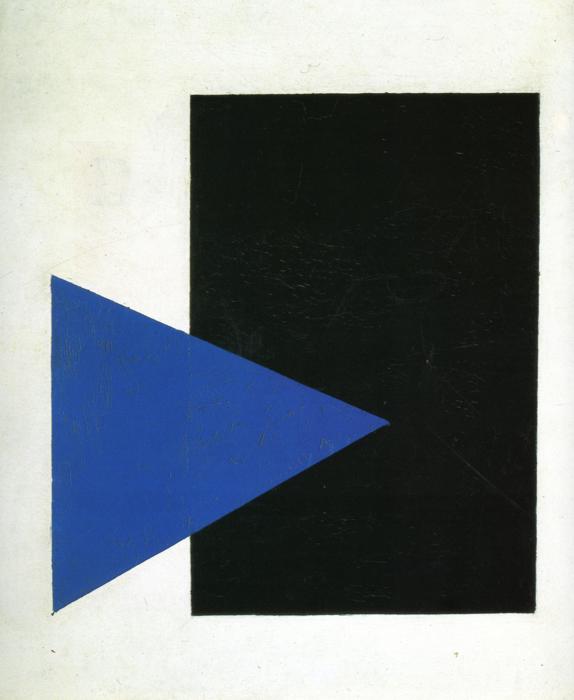

This was a radical departure from art of the time, part of the Suprematism movement that flourished briefly before Stalin suppressed it, heavily and brutally. Art like this was considered subversive, dangerous and a real threat to the morality of the citizenry. Not bad for two simple shapes, is it? And, yet, many people will look at this and use of the above phrases. There is an enormous range of perception on this very simple (yet deeply complicated) piece of art.

The viewer is, of course, completely entitled to their subjective opinion on art but this is, for many cases, a perceptual issue caused by a lack of familiarity with the intentions, practices and goals of abstract art. When we were still painting pictures of houses and rich people, there were many pictures from the 16th to 18th century which contain really badly painted animals. It’s worth going to an historical art museum just to look at all the crap animals. Looking at early European artists trying to capture Australian fauna gives you the same experience – people weren’t painting what they were seeing, they were painting a reasonable approximation of the representation and putting that into the picture. Yet this was accepted and it was accepted because it was a commonly held perception. This also explains offensive (and totally unrealistic) caricatures along racial, gender or religious lines: you accept the stereotype as a reasonable portrayal because of shared perception. (And, no, I’m not putting pictures of that up.)

But, when we talk about art or food, it’s easy to get caught up in things like cultural capital, the assets we have that aren’t money but allow us to be more socially mobile. “Knowing” about art, wine or food has real weight in certain social situations, so the background here matters. Thus, to illustrate that two people can look at the same abstract piece and have one be enraptured while the other wants their money back is not a clean perceptual distinction, free of outside influence. We can’t say “human perception is very a personal business” based on this alone because there are too many arguments to be made about prior knowledge, art appreciation, socioeconomic factors and cultural capital.

But let’s look at another argument starter, the dreaded Monty Hall Problem, where there are three doors, a good prize behind one, and you have to pick a door to try and win a prize. If the host opens a door showing you where the prize isn’t, do you switch or not? (The correctly formulated problem is designed so that switching is the right thing to do but, again, so much argument.) This is, again, a perceptual issue because of how people think about probability and how much weight they invest in their decision making process, how they feel when discussing it and so on. I’ve seen people get into serious arguments about this and this doesn’t even scratch the surface of the incredible abuse Marilyn vos Savant suffered when she had the audacity to post the correct solution to the problem.

This is another great example of what happens when the human perceptual system, environmental factors and facts get jammed together but… it’s also not clean because you can start talking about previous mathematical experience, logical thinking approaches, textual analysis and so on. It’s easy to say that “ah, this isn’t just a human perceptual thing, it’s everything else.”

This is why I love that stupid dress picture. You don’t need to have any prior knowledge of art, cultural capital, mathematical background, history of game shows or whatever. All you need are eyes and relatively functional colour sense of colour. (The dress doesn’t even hit most of the colour blindness issues, interestingly.)

The dress is the clearest example we have that two people can look at the same thing and it’s perception issues that are inbuilt and beyond their control that cause them to have a difference of opinion. We finally have a universal example of how being human is not being sure of the world that we live in and one that we can reproduce anytime we want, without having to carry out any more preparation than “have you seen this dress?”

What we do with it is, as always, the important question now. For me, it’s a reminder to think about issues of perception before I explode with rage across the Internet. Some things will still just be dumb, cruel or evil – the dress won’t heal the world but it does give us a new filter to apply. But it’s simple and clean, and that’s why I think the dress is one of the best things to happen recently to help to bring us together in our discussions so that we can sort out important things and get them done.

Is this a dress thing? #thedress

Posted: March 1, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, blue and black dress, colour palette, community, data visualisation, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, higher education, improving perception, learning, Leonard Nimoy, llap, measurement, perception, perceptual system, principles of design, teaching, teaching approaches, thedress, thinking 1 CommentFor those who missed it, the Internet recently went crazy over llamas and a dress. (If this is the only thing that survives our civilisation, boy, is that sentence going to confuse future anthropologists.) Llamas are cool (there ain’t no karma drama with a llama) so I’m going to talk about the dress. This dress (with handy RGB codes thrown in, from a Wired article I’m about to link to):

When I first saw it, and I saw it early on, the poster was asking what colour it was because she’d taken a picture in the store of a blue and black dress and, yet, in the picture she took, it sometimes looked white and gold and it sometimes looked blue and black. The dress itself is not what I’m discussing here today.

Let’s get something out of the way. Here’s the Wired article to explain why two different humans can see this dress as two different colours and be right. Okay? The fact is that the dress that the picture is of is a blue and black dress (which is currently selling like hot cakes, by the way) but the picture itself is, accidentally, a picture that can be interpreted in different ways because of how our visual perception system works.

This isn’t a hoax. There aren’t two images (or more). This isn’t some elaborate Alternative Reality Game prank.

But the reaction to the dress itself was staggering. In between other things, I plunged into a variety of different social fora to observe the reaction. (Other people also noticed this and have written great articles, including this one in The Atlantic. Thanks for the link, Marc!) The reactions included:

- Genuine bewilderment on the part of people who had already seen both on the same device at nearly adjacent times and were wondering if they were going mad.

- Fierce tribalism from the “white and gold” and “black and blue” camps, within families, across social groups as people were convinced that the other people were wrong.

- People who were sure that it was some sort of elaborate hoax with two images. (No doubt, Big Dress was trying to cover something up.)

- Bordering-on-smug explanations from people who believed that seeing it a certain way indicated that they had superior “something or other”, where you can put day vision/night vision/visual acuity/colour sense/dressmaking skill/pixel awareness/photoshop knowledge.

- People who thought it was interesting and wondered what was happening.

- Attention policing from people who wanted all of social media to stop talking about the dress because we should be talking about (insert one or more) llamas, Leonard Nimoy (RIP, LLAP, \\//) or the disturbingly short lifespan of Russian politicians.

The issue to take away, and the reason I’ve put this on my education blog, is that we have just had an incredibly important lesson in human behavioural patterns. The (angry) team formation. The presumption that someone is trying to make us feel stupid, playing a prank on us. The inability to recognise that the human perceptual system is, before we put any actual cognitive biases in place, incredibly and profoundly affected by the processing shortcuts our perpetual systems take to give us a view of the world.

I want to add a new question to all of our on-line discussion: is this a dress thing?

There are matters that are not the province of simple perceptual confusion. Human rights, equality, murder, are only three things that do not fall into the realm of “I don’t quite see what you see”. Some things become true if we hold the belief – if you believe that students from background X won’t do well then, weirdly enough, then they don’t do well. But there are areas in education when people can see the same things but interpret them in different ways because of contextual differences. Education researchers are well aware that a great deal of what we see and remember about school is often not how we learned but how we were taught. Someone who claims that traditional one-to-many lecturing, as the only approach, worked for them, when prodded, will often talk about the hours spent in the library or with study groups to develop their understanding.

When you work in education research, you get used to people effectively calling you a liar to your face because a great deal of our research says that what we have been doing is actually not a very good way to proceed. But when we talk about improving things, we are not saying that current practitioners suck, we are saying that we believe that we have evidence and practice to help everyone to get better in creating and being part of learning environments. However, many people feel threatened by the promise of better, because it means that they have to accept that their current practice is, therefore, capable of improvement and this is not a great climate in which to think, even to yourself, “maybe I should have been doing better”. Fear. Frustration. Concern over the future. Worry about being in a job. Constant threats to education. It’s no wonder that the two sides who could be helping each other, educational researchers and educational practitioners, can look at the same situation and take away both a promise of a better future and a threat to their livelihood. This is, most profoundly, a dress thing in the majority of cases. In this case, the perceptual system of the researchers has been influenced by research on effective practice, collaboration, cognitive biases and the operation of memory and cognitive systems. Experiment after experiment, with mountains of very cautious, patient and serious analysis to see what can and can’t be learnt from what has been done. This shows the world in a different colour palette and I will go out on a limb and say that there are additional colours in their palette, not just different shades of existing elements. The perceptual system of other people is shaped by their environment and how they have perceived their workplace, students, student behaviour and the personalisation and cognitive aspects that go with this. But the human mind takes shortcuts. Makes assumptions. Has biasses. Fills in gaps to match the existing model and ignores other data. We know about this because research has been done on all of this, too.

You look at the same thing and the way your mind works shapes how you perceive it. Someone else sees it differently, You can’t understand each other. It’s worth asking, before we deploy crushing retorts in electronic media, “is this a dress thing?”

The problem we have is exactly as we saw from the dress: how we address the situation where both sides are convinced that they are right and, from a perceptual and contextual standpoint, they are. We are now in the “post Dress” phase where people are saying things like “Oh God, that dress thing. I never got the big deal” whether they got it or not (because the fad is over and disowning an old fad is as faddish as a fad) and, more reflectively, “Why did people get so angry about this?”

At no point was arguing about the dress colour going to change what people saw until a certain element in their perceptual system changed what it was doing and then, often to their surprise and horror, they saw the other dress! (It’s a bit H.P. Lovecraft, really.) So we then had to work out how we could see the same thing and both be right, then talk about what the colour of the dress that was represented by that image was. I guarantee that there are people out in the world still who are convinced that there is a secret white and gold dress out there and that they were shown a picture of that. Once you accept the existence of these people, you start to realise why so many Internet arguments end up descending into the ALL CAPS EXCHANGE OF BALLISTIC SENTENCES as not accepting that what we personally perceive as being the truth could not be universally perceived is one of the biggest causes of argument. And we’ve all done it. Me, included. But I try to stop myself before I do it too often, or at all.

We have just had a small and bloodless war across the Internet. Two teams have seized the same flag and had a fierce conflict based on the fact that the other team just doesn’t get how wrong they are. We don’t want people to be bewildered about which way to go. We don’t want to stay at loggerheads and avoid discussion. We don’t want to baffle people into thinking that they’re being fooled or be condescending.

What we want is for people to recognise when they might be looking at what is, mostly, a perceptual problem and then go “Oh” and see if they can reestablish context. It won’t always work. Some people choose to argue in bad faith. Some people just have a bee in their bonnet about some things.

“Is this a dress thing?”

In amongst the llamas and the Vulcans and the assassination of Russian politicians, something that was probably almost as important happened. We all learned that we can be both wrong and right in our perception but it is the way that we handle the situation that truly determines whether we’re handling the situation in the wrong or right way. I’ve decided to take a two week break from Facebook to let all of the latent anger that this stirred up die down, because I think we’re going to see this venting for some time.

Maybe you disagree with what I’ve written. That’s fine but, first, ask yourself “Is this a dress thing?”

Live long and prosper.

That’s not the smell of success, your brain is on fire.

Posted: February 11, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, Henry Ford, higher education, in the student's head, industrial research, learning, measurement, multi-tasking, reflection, resources, student perspective, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, working memory, workload Leave a commentI’ve written before about the issues of prolonged human workload leading to ethical problems and the fact that working more than 40 hours a week on a regular basis is downright unproductive because you get less efficient and error-prone. This is not some 1968 French student revolutionary musing on what benefits the soul of a true human, this is industrial research by Henry Ford and the U.S. Army, neither of whom cold be classified as Foucault-worshipping Situationist yurt-dwelling flower children, that shows that there are limits to how long you can work in a sustained weekly pattern and get useful things done, while maintaining your awareness of the world around you.

The myth won’t die, sadly, because physical presence and hours attending work are very easy to measure, while productive outputs and their origins in a useful process on a personal or group basis are much harder to measure. A cynic might note that the people who are around when there is credit to take may end up being the people who (reluctantly, of course) take the credit. But we know that it’s rubbish. And the people who’ve confirmed this are both philosophers and the commercial sector. One day, perhaps.

But anyone who has studied cognitive load issues, the way that the human thinking processes perform as they work and are stressed, will be aware that we have a finite amount of working memory. We can really only track so many things at one time and when we exceed that, we get issues like the helmet fire that I refer to in the first linked piece, where you can’t perform any task efficiently and you lose track of where you are.

So what about multi-tasking?

Ready for this?

We don’t.

There’s a ton of research on this but I’m going to link you to a recent article by Daniel Levitin in the Guardian Q&A. The article covers the fact that what we are really doing is switching quickly from one task to another, dumping one set of information from working memory and loading in another, which of course means that working on two things at once is less efficient than doing two things one after the other.

But it’s more poisonous than that. The sensation of multi-tasking is actually quite rewarding as we get a regular burst of the “oooh, shiny” rewards our brain gives us for finding something new and we enter a heightened state of task readiness (fight or flight) that also can make us feel, for want of a better word, more alive. But we’re burning up the brain’s fuel at a fearsome rate to be less efficient so we’re going to tire more quickly.

Get the idea? Multi-tasking is horribly inefficient task switching that feels good but makes us tired faster and does things less well. But when we achieve tiny tasks in this death spiral of activity, like replying to an e-mail, we get a burst of reward hormones. So if your multi-tasking includes something like checking e-mails when they come in, you’re going to get more and more distracted by that, to the detriment of every other task. But you’re going to keep doing them because multi-tasking.

I regularly get told, by parents, that their children are able to multi-task really well. They can do X, watch TV, do Y and it’s amazing. Well, your children are my students and everything I’ve seen confirms what the research tells me – no, they can’t but they can give a convincing impression when asked. When you dig into what gets produced, it’s a different story. If someone sits down and does the work as a single task, it will take them a shorter time and they will do a better job than if they juggle five things. The five things will take more than five times as long (up to 10, which really blows out time estimation) and will not be done as well, nor will the students learn about the work in the right way. (You can actually sabotage long term storage by multi-tasking in the wrong way.) The most successful study groups around the Uni are small, focused groups that stay on one task until it’s done and then move on. The ones with music and no focus will be sitting there for hours after the others are gone. Fun? Yes. Efficient? No. And most of my students need to be at least reasonably efficient to get everything done. Have some fun but try to get all the work done too – it’s educational, I hear. 🙂

It’s really not a surprise that we haven’t changed humanity in one or two generations. Our brains are just not built in a way that can (yet) provide assistance with the quite large amount of work required to perform multi-tasking.

We can handle multiple tasks, no doubt at all, but we’ve just got to make sure, for our own well-being and overall ability to complete the task, that we don’t fall into the attractive, but deceptive, trap that we are some sort of parallel supercomputer.

We don’t need no… oh, wait. Yes, we do. (@pwc_AU)

Posted: February 11, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, Australia, community, education, educational research, ethics, feedback, G20, higher education, learning, measurement, pricewaterhousecoopers, pwc, reflection, resources, science and technology, thinking, tools Leave a commentThe most important thing about having a good idea is not the idea itself, it’s doing something with it. In the case of sharing knowledge, you have to get good at communication or the best ideas in the world are going to be ignored. (Before anyone says anything, please go and review the advertising industry which was worth an estimated 14 billion pounds in 2013 in the UK alone. The way that you communicate ideas matters and has value.)

Knowledge doesn’t leap unaided into most people’s heads. That’s why we have teachers and educational institutions. There are auto-didacts in the world and most people can pull themselves up by their bootstraps to some extent but you still have to learn how to read and the more expertise you can develop under guidance, the faster you’ll be able to develop your expertise later on (because of how your brain works in terms of handling cognitive load in the presence of developed knowledge.)

When I talk about the value of making a commitment to education, I often take it down to two things: ongoing investment and excellent infrastructure. You can’t make bricks without clay and clay doesn’t turn into bricks by itself. But I’m in the education machine – I’m a member of the faculty of a pretty traditional University. I would say that, wouldn’t I?

That’s why it’s so good to see reports coming out of industry sources to confirm that, yes, education is important because it’s one of the many ways to drive an economy and maintain a country’s international standing. Many people don’t really care if University staff are having to play the banjo on darkened street corners to make ends meet (unless the banjo is too loud or out of tune) but they do care about things like collapsing investments and being kicked out of the G20 to be replaced by nations that, until recently, we’ve been able to list as developing.

PricewaterhouseCoopers (pWc) have recently published a report where they warn that over-dependence on mining and lack of investment in science and technology are going to put Australia in a position where they will no longer be one of the world’s 20 largest economies but will be relegated, replaced by Vietnam and Nigeria. If fact, the outlook is bleaker than that, moving Australia back beyond Bangladesh and Iran, countries that are currently receiving international support. This is no slur on the countries that are developing rapidly, improving conditions for their citizens and heading up. But it is an interesting reflection on what happens to a developed country when it stops trying to do anything new and gets left behind. Of course, science and technology (STEM) does not leap fully formed from the ground so this, in terms, means that we’re going to have make sure that our educational system is sufficiently strong, well-developed and funded to be able to produce the graduates who can then develop the science and technology.

We in the educational community and surrounds have been saying this for years. You can’t have an innovative science and technology culture without strong educational support and you can’t have a culture of innovation without investment and infrastructure. But, as I said in a recent tweet, you don’t have to listen to me bang on about “social contracts”, “general benefit”, “universal equity” and “human rights” to think that investing in education is a good idea. PwC is a multi-national company that’s the second largest professional services company in the world, with annual revenues around $34 billion. And that’s in hard American dollars, which are valuable again compared to the OzD. PwC are serious money people and they think that Australia is running a high risk if we don’t start looking at serious alternatives to mining and get our science and technology engines well-lubricated and running. And running quickly.

The first thing we have to do is to stop cutting investment in education. It takes years to train a good educator and it takes even longer to train a good researcher at University on top of that. When we cut funding to Universities, we slow our hiring, which stops refreshment, and we tend to offer redundancies to expensive people, like professors. Academic staff are not interchangeable cogs. After 12 years of school, they undertake somewhere along the lines of 8-10 years of study to become academics and then they really get useful about 10 years after that through practice and the accumulation of experience. A Professor is probably 30 years of post-school investment, especially if they have industry experience. A good teacher is 15+. And yet these expensive staff are often targeted by redundancies because we’re torn between the need to have enough warm bodies to put in front of students. So, not only do we need to stop cutting, we need to start spending and then commit to that spending for long enough to make a difference – say 25 years.

The next thing, really at the same time, we need to do is to foster a strong innovation culture in Australia by providing incentives and sound bases for research and development. This is (despite what happened last night in Parliament) not the time to be cutting back, especially when we are subsidising exactly those industries that are not going to keep us economically strong in the future.

But we have to value education. We have to value teachers. We have to make it easier for people to make a living while having a life and teaching. We have to make education a priority and accept the fact that every dollar spent in education is returned to us in so many different ways, but it’s just not easy to write it down on a balance sheet. PwC have made it clear: science and technology are our future. This means that good, solid educational systems from the start of primary to tertiary and beyond are now one of the highest priorities we can have or our country is going to sink backwards. The sheep’s back we’ve been standing on for so long will crush us when it rolls over and dies in a mining pit.

I have many great ethical and social arguments for why we need to have the best education system we can have and how investment is to the benefit of every Australia. PwC have just provided a good financial argument for those among us who don’t always see past a 12 month profit and loss sheet.

Always remember, the buggy whip manufacturers are the last person to tell you not to invest in buggy whips.

I Am Self-righteous, You Are Loud, She is Ignored

Posted: February 9, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, discussion, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, Lani Guinier, learning, reflection, scientific theory, student perspective, students, teaching, tools Leave a commentIf we’ve learned anything from recent Internet debates that have become almost Lovecraftian in the way that a single word uttered in the wrong place can cause an outbreaking of chaos, it is that the establishment of a mutually acceptable tone is the only sensible way to manage any conversation that is conducted outside of body-language cues. Or, in short, we need to work out how to stop people screaming at each other when they’re safely behind their keyboards or (worse) anonymity.

As a scientist, I’m very familiar with the approach that says that all ideas can be questioned and it is only by ferocious interrogation of reality, ideas, theory and perception that we can arrive at a sound basis for moving forward.

But, as a human, I’m aware that conducting ourselves as if everyone is made of uncaring steel is, to be put it mildly, a very poor way to educate and it’s a lousy way to arrive at complex consensus. In fact, while we claim such an approach is inherently meritocratic, as good ideas must flourish under such rigour, it’s more likely that we will only hear ideas from people who can endure the system, regardless of whether those people have the best ideas. A recent book, “The Tyranny of the Meritocracy” by Lani Guinier, looks at how supposedly meritocratic systems in education are really measures of privilege levels prior to going into education and that education is more about cultivating merit, rather than scoring a measure of merit that is actually something else.

This isn’t to say that face-to-face arguments are isolated from the effects that are caused by antagonists competing to see who can keep making their point for the longest time. If one person doesn’t wish to concede the argument but the other can’t see any point in making progress, it is more likely for the (for want of a better term) stubborn party to claim that they have won because they have reached a point where the other person is “giving up”. But this illustrates the key flaw that underlies many arguments – that one “wins” or “loses”.

In scientific argument, in theory, we all get together in large rooms, put on our discussion togas and have at ignorance until we force it into knowledge. In reality, what happens is someone gets up and presents and the overall impression of competency is formed by:

- The gender, age, rank, race and linguistic grasp of the speaker

- Their status in the community

- How familiar the audience are with the work

- How attentive the audience are and whether they’re all working on grants or e-mail

- How much they have invested in the speaker being right or wrong

- Objective scientific assessment

We know about the first one because we keep doing studies that tell us that women cannot be assessed fairly by the majority of people, even in blind trials where all that changes on a CV is the name. We know that status has a terrible influence on how we perceive people. Dunning-Kruger (for all of its faults) and novelty effects influence how critical we can be. We can go through all of these and we come back to the fact that our pure discussion is tainted by the rituals and traditions of presentation, with our vaunted scientific objectivity coming in after we’ve stripped off everything else.

It is still there, don’t get me wrong, but you stand a much better chance of getting a full critical hearing with a prepared, specialist audience who have come together with a clear intention to attempt to find out what is going on than an intention to destroy what is being presented. There is always going to be something wrong or unknown but, if you address the theory rather than the person, you’ll get somewhere.

I often refer to this as the difference between scientists and lawyers. If we’re tying to build a better science then we’re always trying to improve understanding through genuine discovery. Defence lawyers are trying to sow doubt in the mind of judges and juries, invalidating evidence for reasons that are nothing to do with the strength of the evidence, and preventing wider causal linkages from forming that would be to the detriment of their client. (Simplistic, I know.)

Any scientific theory must be able to stand up to scientific enquiry because that’s how it works. But the moment we turn such a process into an inquisition where the process becomes one that the person has to endure then we are no longer assessing the strength of the science – we are seeing if we can shout someone into giving up.

As I wrote in the title, when we are self-righteous, whether legitimately or not, we will be happy to yell from the rooftops. If someone else is doing it with us then we might think they are loud but how can someone else’s voice be heard if we have defined all exchange in terms of this exhausting primal scream? If that person comes from a traditionally under-represented or under-privileged group then they may have no way at all to break in.

The mutual establishment of tone is essential if we to hear all of the voices who are able to contribute to the improvement and development of ideas and, right now, we are downright terrible at it. For all we know, the cure for cancer has been ignored because it had the audacity to show up in the mind of a shy, female, junior researcher in a traditionally hierarchical lab that will let her have her own ideas investigated when she gets to be a professor.

Or it it would have occurred to someone had she received education but she’s stuck in the fields and won’t ever get more than a grade 5 education. That’s not a meritocracy.

One of the reasons I think that we’re so bad at establishing tone and seeing past the illusion of meritocracy is the reason that we’ve always been bad at handling bullying: we are more likely to see a spill-over reaction from the target than the initial action except in the most obvious cases of physical bullying. Human language and body-assisted communication are subtle and words are more than words. Let’s look at this sentence:

“I’m sure he’s doing the best he can.”

You can adjust this sentence to be incredibly praising, condescending, downright insulting, dismissive and indifferent without touching the content of the sentence. But, written like this, it is robbed of tone and context. If someone has been “needled” with statements like this for months, then a sudden outburst is increasingly likely, especially in stressful situations. This is the point at which someone says “But I only said … ” If our workplaces our innately rife with inter-privilege tension and high stress due to the collapse of the middle class – no wonder people blow up!

We have the same problem in the on-line community from an approach called Sea-Lioning, where persistent questioning is deployed in a way that, with each question isolated, appears innocuous but, as a whole, forms a bullying technique to undermine and intimidate the original writer. Now some of this is because there are people who honestly cannot tell what a mutually respectful tone look like and really want to know the answer. But, if you look at the cartoon I linked to, you can easily see how this can be abused and, in particular, how it can be used to shut down people who are expressing ideas in new space. We also don’t get the warning signs of tone. Worse still, we often can’t or don’t walk away because we maintain a connection that the other person can jump on anytime they want to. (The best thing you can do sometimes on Facebook is to stop notifications because you stop getting tapped on the shoulder by people trying to get up your nose. It is like a drink of cool water on a hot day, sometimes. I do, however, realise that this is easier to say than do.)

When students communicate over our on-line forums, we do keep an eye on them for behaviour that is disrespectful or downright rude so that we can step in and moderate the forum, but we don’t require moderation before comment. Again, we have the notion that all ideas can be questioned, because SCIENCE, but the moment we realise that some questions can be asked not to advance the debate but to undermine and intimidate, we have to look very carefully at the overall context and how we construct useful discussion, without being incredibly prescriptive about what form discussion takes.

I recently stepped in to a discussion about some PhD research that was being carried out at my University because it became apparent that someone was acting in, if not bad faith, an aggressive manner that was not actually achieving any useful discussion. When questions were answered, the answers were dismissed, the argument recast and, to be blunt, a lot of random stuff was injected to discredit the researcher (for no good reason). When I stepped in to point out that this was off track, my points were side-stepped, a new argument came up and then I realised that I was dealing with a most amphibious mammal.

The reason I bring this up is that when I commented on the post, I immediately got positive feedback from a number of people on the forum who had been uncomfortable with what had been going on but didn’t know what to do about it. This is the worst thing about people who set a negative tone and hold it down, we end up with social conventions of politeness stopping other people from commenting or saying anything because it’s possible that the argument is being made in good faith. This is precisely the trap a bad faith actor wants to lock people into and, yet, it’s also the thing that keeps most discussions civil.

Thanks, Internet trolls. You’re really helping to make the world a better place.

These days my first action is to step in and ask people to clarify things, in the most non-confrontational way I can muster because asking people “What do you mean” can be incredibly hostile by itself! This quickly establishes people who aren’t willing to engage properly because they’ll start wriggling and the Sea-Lion effect kicks in – accusations of rudeness, unwillingness to debate – which is really, when it comes down to it:

I WANT TO TALK AT YOU LIKE THIS HOW DARE YOU NOT LET ME DO IT!

This isn’t the open approach to science. This is thuggery. This is privilege. This is the same old rubbish that is currently destroying the world because we can’t seem to be able to work together without getting caught up in these stupid games. I dream of a better world where people can say any combination of “I use Mac/PC/Java/Python” without being insulted but I am, after all, an Idealist.

The summary? The merit of your argument is not determined by how loudly you shout and how many other people you silence.

I expect my students to engage with each other in good faith on the forums, be respectful and think about how their actions affect other people. I’m really beginning to wonder if that’s the best preparation for a world where a toxic on-line debate can break over into the real world, where SWAT team attacks and document revelation demonstrate what happens when people get too carried away in on-line forums.

We’re stopping people from being heard when they have something to say and that’s wrong, especially when it’s done maliciously by people who are demanding to say something and then say nothing. We should be better at this by now.

In Praise of the Beautiful Machines

Posted: February 1, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, AI, artificial intelligence, authenticity, beautiful machine, beautiful machines, Bill Gates, blogging, community, design, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, Google, higher education, in the student's head, Karlheinz Stockhausen, learning, measurement, Philippa Foot, self-driving car, teaching approaches, thinking, thinking machines, tools Leave a commentI posted recently about the increasingly negative reaction to the “sentient machines” that might arise in the future. Discussion continues, of course, because we love a drama. Bill Gates can’t understand why more people aren’t worried about the machine future.

…AI could grow too strong for people to control.

Scientists attending the recent AI conference (AAAI15) thinks that the fears are unfounded.

“The thing I would say is AI will empower us not exterminate us… It could set AI back if people took what some are saying literally and seriously.” Oren Etzioni, CEO of the Allen Institute for AI.

If you’ve read my previous post then you’ll know that I fall into the second camp. I think that we don’t have to be scared of the rise of the intelligent AI but the people at AAAI15 are some of the best in the field so it’s nice that they ask think that we’re worrying about something that is far, far off in the future. I like to discuss these sorts of things in ethics classes because my students have a very different attitude to these things than I do – twenty five years is a large separation – and I value their perspective on things that will most likely happen during their stewardship.

I asked my students about the ethical scenario proposed by Philippa Foot, “The Trolley Problem“. To summarise, a runaway trolley is coming down the tracks and you have to decide whether to be passive and let five people die or be active and kill one person to save five. I put it to my students in terms of self-driving cars where you are in one car by yourself and there is another car with five people in it. Driving along a bridge, a truck jackknifes in front of you and your car has to decide whether to drive ahead and kill you or move to the side and drive the car containing five people off the cliff, saving you. (Other people have thought about in the context of Google’s self-driving cars. What should the cars do?)

One of my students asked me why the car she was in wouldn’t just put on the brakes. I answered that it was too close and the road was slippery. Her answer was excellent:

Why wouldn’t a self-driving car have adjusted for the conditions and slowed down?

Of course! The trolley problem is predicated upon the condition that the trolley is running away and we have to make a decision where only two results can come out but there is no “runaway” scenario for any sensible model of a self-driving car, any more than planes flip upside down for no reason. Yes, the self-driving car may end up in a catastrophic situation due to something totally unexpected but the everyday events of “driving too fast in the wet” and “chain collision” are not issues that will affect the self-driving car.

But we’re just talking about vaguely smart cars, because the super-intelligent machine is some time away from us. What is more likely to happen soon is what has been happening since we developed machines: the ongoing integration of machines into human life to make things easier. Does this mean changes? Well, yes, most likely. Does this mean the annihilation of everything that we value? No, really not. Let me put this in context.

As I write this, I am listening to two compositions by Karlheinz Stockhausen, playing simultaneously but offset, “Kontakte” and “Telemusik“, works that combine musical instruments, electronic sounds, and tape recordings. I like both of them but I prefer to listen to the (intentionally sterile) Telemusik by starting Koktakte first for 2:49 and then kicking off Telemusik, blending the two and finishing on the longer Kontakte. These works, which are highly non-traditional and use sound in very different ways to traditional orchestral arrangement, may sound quite strange and, to an audience familiar with popular music quite strange, they were written in 1959 and 1966 respectively. These innovative works are now in their middle-age. They are unusual works, certainly, and a number of you will peer at your speakers one they start playing but… did their production lead to the rejection of the popular, classic, rock or folk music output of the 1960s? No.

We now have a lot of electronic music, synthesisers, samplers, software-driven music software, but we still have musicians. It’s hard to measure the numbers (this link is very good) but electronic systems have allowed us to greatly increase the number of composers although we seem to be seeing a slow drop in the number of musicians. In many ways, the electronic revolution has allowed more people to perform because your band can be (for some purposes) a band in a box. Jazz is a different beast, of course, as is classical, due to the level of training and study required. Jazz improvisation is a hard problem (you can find papers on it from 2009 onwards and now buy a so-so jazz improviser for your iPad) and hard problems with high variability are not easy to solve, even computationally.

So the increased portability of music via electronic means has an impact in some areas such as percussion, pop, rock, and electronic (duh) but it doesn’t replace the things where humans shine and, right now, a trained listener is going to know the difference.

I have some of these gadgets in my own (tiny) studio and they’re beautiful. They’re not as good as having the London Symphony Orchestra in your back room but they let me create, compose and put together pleasant sounding things. A small collection of beautiful machines make my life better by helping me to create.

Now think about growing older. About losing strength, balance, and muscular control. About trying to get out of bed five times before you succeed or losing your continence and having to deal with that on top of everything else.

Now think about a beautiful machine that is relatively smart. It is tuned to wrap itself gently around your limbs and body to support you, to help you keep muscle tone safely, to stop you from falling over, to be able to walk at full speed, to take you home when you’re lost and with a few controlling aspects to allow you to say when and where you go to the bathroom.

Isn’t that machine helping you to be yourself, rather than trapping you in the decaying organic machine that served you well until your telomerase ran out?

Think about quiet roads with 5% of the current traffic, where self-driving cars move from point to point and charge themselves in between journeys, where you can sit and read or work as you travel to and from the places you want to go, where there are no traffic lights most of the time because there is just a neat dance between aware vehicles, where bad weather conditions means everyone slows down or even deliberately link up with shock absorbent bumper systems to ensure maximum road holding.

Which of these scenarios stops you being human? Do any of them stop you thinking? Some of you will still want to drive and I suppose that there could be roads set aside for people who insisted upon maintaining their cars but be prepared to pay for the additional insurance costs and public risk. From this article, and the enclosed U Texas report, if only 10% of the cars on the road were autonomous, reduced injuries and reclaimed time and fuel would save $37 billion a year. At 90%, it’s almost $450 billion a year. The Word Food Programme estimates that $3.2 billion would feed the 66,000,000 hungry school-aged children in the world. A 90% autonomous vehicle rate in the US alone could probably feed the world. And that’s a side benefit. We’re talking about a massive reduction in accidents due to human error because (ta-dahh) no human control.

Most of us don’t actually drive our cars. They spend 5% of their time on the road, during which time we are stuck behind other people, breathing fumes and unable to do anything else. What we think about as the pleasurable experience of driving is not the majority experience for most drivers. It’s ripe for automation and, almost every way you slice it, it’s better for the individual and for society as a whole.

But we are always scared of the unknown. There’s a reason that the demons of myth used to live in caves and under ground and come out at night. We hate the dark because we can’t see what’s going on. But increased machine autonomy, towards machine intelligence, doesn’t have to mean that we create monsters that want to destroy us. The far more likely outcome is a group of beautiful machines that make it easier and better for us to enjoy our lives and to have more time to be human.

We are not competing for food – machines don’t eat. We are not competing for space – machines are far more concentrated than we are. We are not even competing for energy – machines can operate in more hostile ranges than we can and are far more suited for direct hook-up to solar and wind power, with no intermediate feeding stage.

We don’t have to be in opposition unless we build machines that are as scared of the unknown as we are. We don’t have to be scared of something that might be as smart as we are.

If we can get it right, we stand to benefit greatly from the rise of the beautiful machine. But we’re not going to do that by starting from a basis of fear. That’s why I told you about that student. She’d realised that our older way of thinking about something was based on a fear of losing control when, if we handed over control properly, we would be able to achieve something very, very valuable.

A Meditation on the Cultivation of Education

Posted: January 2, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: agriculture, authenticity, community, cultivation, education, educational problem, gourd, higher education, learning, pumpkin, teaching, thinking Leave a comment“In our reasonings concerning matter of fact, there are all imaginable degrees of assurance, from the highest certainty to the lowest species of moral evidence. A wise man, therefore, proportions his belief to the evidence.”

David Hume, Section 10, Of Miracles, Part 1, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, 1758.

Why haven’t we “fixed” education yet? Does it actually need to be fixed in the first place? In a recent post, I discussed five things that we needed to assume were true, to avoid the self-fulfilling and negative outcomes should we assume that they were false. One of these was that fixing things was something we should be doing and the evidence does appear to support me on that. I wouldn’t call myself a wise man, although I’m definitely learning as I grow older, but my belief in this matter is proportional to the evidence available to me. And that evidence is both vast and convincing; change is required.

One of the biggest problems it that many attempts have been made and are being made on a daily basis to “fix” education and, yet, we seem to have many horror stories of these not working. Or, maybe something good was done, but it “won’t work here”. There are some places that regularly maintain high standards of education and this recent post in the Washington Post Answer Sheet Blog talked about how Finland does it. They don’t test teacher effectiveness as their main measure of achievement, they conduct a highly structured and limited entry program for teachers, requiring a masters level degree to teach above the most junior levels of school. By training teachers well and knowing what path people must take to become teachers, we can greatly raise the probability of getting good teachers at the end of the process. Teachers can then work together in schools to achieve good outcomes. That is, there is an excellent teaching environment, and the school plus the educational system plus the teachers can then help to overcome the often amazingly dominant factors of socioeconomic status, family and peer influence.

Finland has looked across the problem of education and carefully thought out how they can develop everything that is needed for success in order to be able to cultivate a successful educational environment for their staff and students. They develop an educational culture that is evidence-based and highly informed – no wonder they’re doing well.

If we look at the human traditions of agricultural cultivation, it’s easy to see why any piecemeal approach to education is almost doomed to fail because we cannot put in enough positives at one point to overcome negatives at another. About 11-12,000 years ago, humans started taking note of crops and living in a more fixed manner, cultivating crops around them. At this stage, humans were opportunistically taking advantage of crops that were already growing, in places that could sustain them. As our communities grew, we needed to start growing more specific crops to accommodate our growing needs and selection (starting with the mighty gourd, I believe) of more desirable variants of a crop lead to the domesticated varieties we enjoy today.

But plants need what they have always needed: enough sunlight, enough food, enough water, enough fertilisation/pollination. Successful agriculture depends upon the ability to determine what is required from the evidence and provide this. Once we started setting up old crops in new places, we race across new problems. If a plant has not succeeded somewhere naturally, then it is either because it didn’t reach there or it has already failed there. Working out which crop will work where is a vital element of agriculture because the amount of effort required to make something grow where it wouldn’t normally grow is immense. (Australia’s history of monstrous over-irrigation to support citrus crops and rice is a dark reminder of what happens when hubris overrides evidence.)

After 12,000 years, we pretty much know what’s required (pretty much) and we can even support diverse environments such as aquaculture, hydroponics, organic culture and so on. Monoculture agriculture is not just a bad idea at the system level but our dependency on monocultural food varieties (hello, Cavendish Banana) is also a very bad idea. When everything we depend upon has the same weakness, we are not in a very safe position. The demand for food is immense and we must be systematic and efficient in our food production, while still (in many parts of the world) striving to be ethical and sustainable so that feeding people now will not starve other people, now or in the future, nor be any more cruel than it needs to be to sustain human life. (I leave further ethical discussion of human vs animal life to Professor Peter Singer.)

Everything we have domesticated now was a weed or wild animal once: a weed is just a wild plant that grows and isn’t cultivated. Before we leap to any conclusions about what is and what isn’t valuable, it’s important to remember how much more quickly we can domesticate crops these days but, also, that we’re building on 12,000 years of previous work. And it’s solid work. It’s highly informative work. You can’t make complex systems work by prodding one bit and hoping.

Now, strangely, when we look at educational systems, we can’t seem to transfer the cultivation metaphor effectively – or, at least, many in power can’t. A good teaching environment has enough resources (food and water), the right resources (enough potassium and not too much acid, for example), has good staff (illumination taking the place of sunlight to provide energy) and we have space for innovation and development. If we want the best yield, then we apply this to all of our crops: if we want an educated populace, we must make this available to all citizens. If we put any one these in place, due to limited resources or pilot project mentality, then it is hardly going to be surprising if the project fails. How can great teachers do anything with a terminally under-resourced classroom? What point is there in putting computers into every classroom if there is no-one who is trained to teach with them, if students don’t all have the same experience at home (and hence we enhance the digital divide) or if we are heavily constrained in what we can teach so it is the same old boring stuff but just on new machines?

Yes, some plants will survive in a constrained environment and some can even live on the air but, much like students, this is most definitely not all plants and you have to have enough knowledge to know how to wisely use your resources. Until we accept that fixing the educational system requires us to really work on cultivating the entire environment, we risk continuing to focus on the wrong things. Repeating the same ineffective actions and expecting a new and amazing positive outcome is the very definition of madness. Teachers by themselves are only part of the educational system. Teachers in a good system will do more and go further. Adding respect in the community, resources from the state and an equality of opportunity and application is vital if we are to actually get things working.

I realise students aren’t plants and I’m not encouraging anyone to start weeding, by any stretch of the imagination, but it takes a lot of work to get a complicated environmental system working efficiently and I’m still confused as to why this seems to be such a hard thing for some people to get their heads around. It shouldn’t take us another 12,000 years to get this right – we already know what we really have to do, it just seems really hard for some people to believe it.

5 Things: Necessary Assumptions of Truth