Stats, stats and more stats: The Half Life of Fame

Posted: May 5, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: abelson, education, feedback, half-life of fame, higher education, Korzybski, learning, measurement, MIKE, reflection 4 CommentsSo, here are the stats for my blog, at time of writing. You can see a steady increase in hits over the last few weeks. What does this mean? Have I somehow hit a sweet spot in my L&T discussions? Has my secret advertising campaign paid off (no, not seriously). Well, there are a couple of things in there that are both informative… and humbling.

Firstly, two of the most popular searches that find my blog are “London 2012 tube” and “alone in a crowd”. These hits have probably accounted for about 16% of my traffic for the past three weeks. What does that tell me? Well, firstly, the Olympics aren’t too far away and people are looking for how convenient their hotels are. The second is a bit sadder.

The second search “alone in a crowd” is coming in across two languages – English and Russian. I have picked up a reasonable presence in Russia and Ukraine, mostly from that search term. It seems to contribute a lot to my (Australian) Monday morning feed, which means that a lot of people seem to search for this on Sundays.

But let me show you another graph, and talk about the half life of fame:

That’s since the beginning my blogging activities. That spike at Week 9? That’s when I started blogging SIGCSE and also includes the day when over 100 people jumped on my blog because of a referral from Mark Guzdial. That was also the conference at which Hal Abelson referred to a concept of the Half Life of fame – the inevitable drop away after succeeding at something, if you don’t contribute more. And you can see that pretty clearly in the data. After SIGCSE, I was happily on my way back to being read by about 20-30 people a day, tops, most of whom I knew, because I wasn’t providing much more information to the people who scanned me at SIGCSE.

Without consciously doing it, I’ve managed to put out some articles that appear to have wider appeal and that are now showing up elsewhere. But these stats, showing improvement, are meaningless unless I really know what people are looking at. So, right now I’m pulling apart all of my log data to see what people are actually reading – whether I have an increasing L&T presence and readership, or a lot of sad Russian speakers or lost people on the London Underground system. I’m expecting to see another fall-away very soon now and drop down to the comfortable zone of my little corner of the Internet. I’m not interested in widespread distribution – I’m interesting in getting an inspiring or helpful message to the people who need it. Only one person needs to read this blog for it to be useful. It just has to the right one person. 🙂

One of the most interesting things about doing this, every day, is that you start wondering about whether your effort is worth it. Are people seeking it out? Are people taking the time to read it or just clicking through? Are there a growing number of frustrated Tube travellers thinking “To heck with Korzybski!” Time to go into the data and look. I’m going to keep writing regardless but I’d like to get an idea of where all of this is going.

Grand Challenges – A New Course and a New Program

Posted: May 4, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, challenge, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, equality, grand challenges, higher education, learning, reflection, teaching, universal principles of design Leave a commentOh, the poor students that I spoke to today. We have a new degree program starting, the Bachelor of Computer Science (Advanced), and it’s been given to me to coordinate and set up the first course: Grand Challenges in Computer Science, a first-year offering. This program (and all of its unique components) are aimed at students who have already demonstrated that they have got their academics sorted – a current GPA of 6 or higher (out of 7, that’s A equivalent or Distinctions for those who speak Australian), or an ATAR (Australian Tertiary Admission Rank) of 95+ out of 100. We identified some students who met the criteria and might want to be in the degree, and also sent out a general advertisement as some people were close and might make the criteria with a nudge.

These students know how to do their work and pass their courses. Because of this, we can assume some things and then build to a more advanced level.

Now, Nick, you might be saying, we all know that you’re (not so secretly) all about equality and accessibility. Why are you running this course that seems so… stratified?

Ah, well. Remember when I said you should probably feel sorry for them? I talked to these students about the current NSF Grand Challenges in CS, as I’ve already discussed, and pointed out that, given that the students in question had already displayed a degree of academic mastery, they could go further. In fact, they should be looking to go further. I told them that the course would be hard and that I would expect them to go further, challenge themselves and, as a reward, they’d do amazing things that they could add to their portfolios and their experience bucket.

I showed them that Cholera map and told them how smart data use saved lives. I showed them We Feel Fine and, after a slightly dud demo where everyone I clicked on had drug issues, I got them thinking about the sheer volume of data that is out there, waiting to be analysed, waiting to tell us important stories that will change the world. I pretty much asked them what they wanted to be, given that they’d already shown us what they were capable of. Did they want to go further?

There are so many things that we need, so many problems to solve, so much work to do. If I can get some good students interested in these problems early and provide a coursework system to help them to develop their solutions, then I can help them to make a difference. Do they have to? No, course entry is optional. But it’s so tempting. Small classes with a project-based assessment focus based on data visualisation: analysis, summarisation and visualisation in both static and dynamic areas. Introduction to relevant philosophy, cognitive fallacies, useful front-line analytics, and display languages like R and Processing (and maybe Julia). A chance to present to their colleagues, work with research groups, do student outreach – a chance to be creative and productive.

I, of course, will take as much of the course as I can, having worked on it with these students, and feed parts of it into outreach into schools, send other parts in different levels of our other degrees. Next year, I’ll write a brand new grand challenges course and do it all again. So this course is part of forming a new community core, a group of creative and accomplished leaders, to an extent, but it is also about making this infectious knowledge, a striving point for someone who now knows that a good mark will get them into a fascinating program. But I want all of it to be useful elsewhere, because if it’s good here, then (with enough scaffolding) it will be good elsewhere. Yes, I may have to slow it down elsewhere but that means that the work done here can help many courses in many ways.

I hope to get a good core of students and I’m really looking forward to seeing what they do. Are they up for the challenge? I guess we’ll find out at the end of second semester.

But, so you know, I think that they might be. Am I up for it?

I certainly hope so! 🙂

Saving Lives With Pictures: Seeing Your Data and Proving Your Case

Posted: May 2, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, analytics, authenticity, cholera outbreak, data visualisation, design, education, higher education, learning, teaching, teaching approaches, voronoi 1 Comment

From Wikipedia, original map by John Snow showing the clusters of cholera cases in the London epidemic of 1854

This diagram is fascinating for two reasons: firstly, because we’re human, we wonder about the cluster of black dots and, secondly, because this diagram saved lives. I’m going to talk about the 1854 Broad Street Cholera outbreak in today’s post, but mainly in terms of how the way that you represent your data makes a big difference. There will be references to human waste in this post and it may not be for the squeamish. It’s a really important story, however, so please carry on! I have drawn heavily on the Wikipedia page, as it’s a very good resource in this case, but I hope I have added some good thoughts as well.

19th Century London had a terrible problem with increasing population and an overtaxed sewerage system. Underfloor cesspools were overfilling and the excess was being taken and dumped into the River Thames. Only one problem. Some water companies were taking their supply from the Thames. For those who don’t know, this is a textbook way to distribute cholera – contaminating drinking water with infected human waste. (As it happens, a lack of cesspool mapping meant that people often dug wells near foul ground. If you ever get a time machine, cover your nose and mouth and try not to breath if you go back before 1900.)

But here’s another problem – the idea that germs carried cholera was not the dominant theory at the time. People thought that it was foul air and bad smells (the miasma theory) that carried the bugs. Of course, from this century we can look back and think “Hmm, human waste everywhere, bugs everywhere, bad smells everywhere… ohhh… I see what you did there.” but this is from the benefit of early epidemiological studies such as those of John Snow, a London physician of the 19th Century.

John Snow recorded the locations of the households where cholera had broken out, on the map above. He did this by walking around and talking to people, with the help of a local assistant curate, the Reverend Whitehead, and, importantly, working out what they had in common with each other. This turned out to be a water pump on Broad Street, at the centre of this map. If people got their water from Broad Street then they were much more likely to get sick. (Funnily enough, monks who lived in a monastery adjacent to the pump didn’t get sick. Because they only drank beer. See? It’s good for you!) John Snow was a skeptic of the miasma theory but didn’t have much else to go on. So he went looking for a commonality, in the hope of finding a reason, or a vector. If foul air wasn’t the vector – then what was spreading the disease?

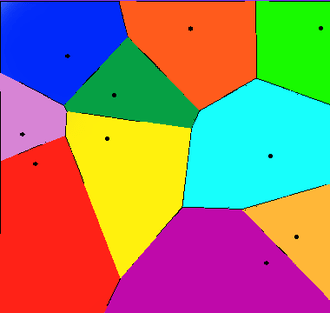

Snow divided the map up into separate compartments that showed the pump and compartment showed all of the people for whom this would be the pump that they used, because it was the closest. This is what we would now call a Voronoi diagram, and is widely used to show things like the neighbourhoods that are serviced by certain shops, or the impacts of roads on access to shops (using the Manhattan Distance).

A Voronoi diagram from Wikipedia showing 10 shops, in a flat city. The cells show the areas that contain all the customers who are closest to the shop in that cell.

What was interesting about the Broad Street cell was that its boundary contained most of the cholera cases. The Broad Street pump was the closest pump to most people who had contracted cholera and, for those who had another pump slightly closer, it was reported to have better tasting water (???) which meant that it was used in preference. (Seriously, the mind boggles on a flavour preference for a pump that was contaminated both by river water and an old cesspit some three feet away.)

Snow went to the authorities with sound statistics based on his plots, his interviews and his own analysis of the patterns. His microscopic analysis had turned up no conclusive evidence, but his patterns convinced the authorities and the handle was taken off the pump the next day. (As Snow himself later said, not many more lives may have been saved by this particular action but it gave credence to the germ theory that went on to displace the miasma theory.)

For those who don’t know, the stink of the Thames was so awful during Summer, and so feared, that people fled to the country where possible. Of course, this option only applied to those with country houses, which left a lot of poor Londoners sweltering in the stink and drinking foul water. The germ theory gave a sound public health reason to stop dumping raw sewage in the Thames because people could now get past the stench and down to the real cause of the problem – the sewage that was causing the stench.

So John Snow had encountered a problem. The current theory didn’t seem to hold up so he went back and analysed the data available. He constructed a survey, arranged the results, visualised them, analysed them statistically and summarised them to provide a convincing argument. Not only is this the start of epidemeology, it is the start of data science. We collect, analyse, summarise and visualise, and this allows us to convince people of our argument without forcing them to read 20 pages of numbers.

This also illustrates the difference between correlation and causation – bad smells were always found with sewage but, because the bad smell was more obvious, it was seen as causative of the diseases that followed the consumption of contaminated food and water. This wasn’t a “people got sick because they got this wrong” situation, this was “households died, with children dying at a rate of 160 per 1000 born, with a lifespan of 40 years for those who lived”. Within 40 years, the average lifespan had gone up 10 years and, while infant mortality didn’t really come down until the early 20th century, for a range of reasons, identifying the correct method of disease transmission has saved millions and millions of lives.

So the next time your students ask “What’s the use of maths/statistics/analysis?” you could do worse than talk to them briefly about a time when people thought that bad smells caused disease, people died because of this idea, and a physician and scientist named John Snow went out, asked some good questions, did some good thinking, saved lives and changed the world.

Oh, Perry. (Our Representation of Intellectual Development, Holds On, Holds on.)

Posted: April 30, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, dualism, education, higher education, learning, measurement, multiplicity, perry, reflection, research, resources, teaching, teaching approaches 1 CommentI’ve spent the weekend working on papers, strategy documents, promotion stuff and trying to deal with the knowledge that we’ve had some major success in one of our research contracts – which means we have to employ something like four staff in the next few months to do all of the work. Interesting times.

One of the things I love about working on papers is that I really get a chance to read other papers and books and digest what people are trying to say. It would be fantastic if I could do this all the time but I’m usually too busy to tear things apart unless I’m on sabbatical or reading into a new area for a research focus or paper. We do a lot of reading – it’s nice to have a focus for it that temporarily trumps other more mundane matters like converting PowerPoint slides.

It’s one thing to say “Students want you to give them answers”, it’s something else to say “Students want an authority figure to identify knowledge for them and tell them which parts are right or wrong because they’re dualists – they tend to think in these terms unless we extend them or provide a pathway for intellectual development (see Perry 70).” One of these statements identifies the problem, the other identifies the reason behind it and gives you a pathway. Let’s go into Perry’s classification because, for me, one of the big benefits of knowing about this is that it stops you thinking that people are stupid because they want a right/wrong answer – that’s just the way that they think and it is potentially possible to change this mechanism or help people to change it for themselves. I’m staying at the very high level here – Perry has 9 stages and I’m giving you the broad categories. If it interests you, please look it up!

We start with dualism – the idea that there are right/wrong answers, known to an authority. In basic duality, the idea is that all problems can be solved and hence the student’s task is to find the right authority and learn the right answer. In full dualism, there may be right solutions but teachers may be in contention over this – so a student has to learn the right solution and tune out the others.

If this sounds familiar, in political discourse and a lot of questionable scientific debate, that’s because it is. A large amount of scientific confusion is being caused by people who are functioning as dualists. That’s why ‘it depends’ or ‘with qualification’ doesn’t work on these people – there is no right answer and fixed authority. Most of the time, you can be dismissed as having an incorrect view, hence tuned out.

As people progress intellectually, under direction or through exposure (or both), they can move to multiplicity. We accept that there can be conflicting answers, and that there may be no true authority, hence our interpretation starts to become important. At this stage, we begin to accept that there may be problems for which no solutions exist – we move into a more active role as knowledge seekers rather than knowledge receivers.

Then, we move into relativism, where we have to support our solutions with reasons that may be contextually dependant. Now we accept that viewpoint and context may make which solution is better a mutable idea. By the end of this category, students should be able to understand the importance of making choices and also sticking by a choice that they’ve made, despite opposition.

This leads us into the final stage: commitment, where students become responsible for the implications of their decisions and, ultimately, realise that every decision that they make, every choice that they are involved in, has effects that will continue over time, changing and developing.

I don’t want to harp on this too much but this indicates one of the clearest divides between people: those who repeat the words of an authority, while accepting no responsibility or ownership, hence can change allegiance instantly; and those who have thought about everything and have committed to a stand, knowing the impact of it. If you don’t understand that you are functioning at very different levels, you may think that the other person is (a) talking down to you or (b) arguing with you under the same expectation of personal responsibility.

Interesting way to think about some of the intractable arguments we’re having at the moment, isn’t it?

Big Data, Big Problems

Posted: April 26, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, higher education, learning, PhD, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a commentMy new PhD student joined our research group on Monday last week (Hi, T) and we’ve already tried to explode his brain by discussing every possible idea that we’ve had about his project area – that we’ve developed over the last year, but that we’ve presented to him in the past week.

He’s still coming to meetings, which is good, because it means that he’s not dead yet. The ideas that we’re dealing with are fairly interesting and build upon some work that I’ve spoken about earlier, where we’ve looked at student data that we happen to have to see if we can determine other behaviours, predict GPA, or get an idea of the likelihood of the student completing their studies.

Our pilot research study is almost written up for submission this Sunday but, like all studies that are conducted after the collection time, we only have the data that was collected rather than the ideal set of data that we would like to collect. That’s one of the things that we’ve given T to think about – what is the complete set of student data that we could collect if we could collect everything?

If we could collect everything, what would be useful? What is duplicated within the collection set? Which of these factors has an impact on things that we care about, like student participation, engagement, level of achievement and development of discipline skills? How can I collect them and store them so that I not only can look at the data in light of today’s thinking but that, twenty years from now, I can completely re-evaluate the data set in different frameworks?

There’s a lot of data out there, there are many ways of collecting, and there are lots of projects in operation. But there are also lots and lots of problems: correlations to find, factors to exclude, privacy and ethical considerations to take into account, storage systems to wrestle with and, at the end of the day, a giant validation issue to make sure that what we’re doing is fundamentally accurate and useful.

I’ve written before about the data deluge but, even when we restrict our data crawling to one small area, it’s sometimes easy to lose track of how complicated our world is and how many pieces of data we can collect.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, for T, there are many good and bad examples to look at, many studies that didn’t quite achieve what was wanted, and a lot of space for him to explore and define his own research. Now if I could only put aside that much time for my own research.

Got Vygotsky?

Posted: April 25, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: Csíkszentmihályi, curriculum, design, education, flow, games, higher education, learning, principles of design, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, tools, vygotsky, Zone of proximal development, ZPD 4 CommentsOne of my colleagues drew my attention to an article in a recent Communications of the ACM, May 2012, vol 55, no 5, (Education: “Programming Goes to School” by Alexander Repenning) discussing how we can broaden participation of women and minorities in CS by integrating game design into middle school curricula (Thanks, Jocelyn!). The article itself is really interesting because it draws on a number of important theories in education and CS education but puts it together with a strong practical framework.

There’s a great diagram in it that shows Challenge versus Skills, and clearly illustrates that if you don’t get the challenge high enough, you get boredom. Set it too high, you get anxiety. In between the two, you have Flow (from Csíkszentmihályi’ s definition, where this indicates being fully immersed, feeling involved and successful) and the zone of proximal development (ZPD).

Which brings me to Vygotsky. Vgotsky’s conceptualisation of the zone of proximal development is designed to capture that continuum between the things that a learner can do with help, and the things that a learner can do without help. Looking at the diagram above, we can now see how learners can move from bored (when their skills exceed their challenges) into the Flow zone (where everything is in balance) but are can easily move into a space where they will need some help.

Most importantly, if we move upwards and out of the ZPD by increasing the challenge too soon, we reach the point where students start to realise that they are well beyond their comfort zone. What I like about the diagram above is that transition arrow from A to B that indicates the increase of skill and challenge that naturally traverses the ZPD but under control and in the expectation that we will return to the Flow zone again. Look at the red arrows – if we wait too long to give challenge on top of a dry skills base, the students get bored. It’s a nice way of putting together the knowledge that most of us already have – let’s do cool things sooner!

That’s one of the key aspects of educational activities – not they are all described in terms educational psychology but they show clear evidence of good design, with the clear vision of keeping students in an acceptably tolerable zone, even as we ramp up the challenges.

One the key quotes from the paper is:

The ability to create a playable game is essential if students are to reach a profound, personally changing “Wow, I can do this” realization.

If we’re looking to make our students think “I can do this”, then it’s essential to avoid the zone of anxiety where their positivity collapses under the weight of “I have no idea how anyone can even begin to help me to do this.” I like this short article and I really like the diagram – because it makes it very clear when we overburden with challenge, rather than building up skill and challenge in a matched way.

This Is What You Want, This Is What You Get

Posted: April 22, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: curriculum, education, higher education, learning, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a commentOne of the discussions that we seem to be having a lot is how the University will change in response to what students want, as we gain more flexibility in delivery and move away from face-to-face (bricks and mortar) to more blended approaches, possibly over distance learning. I’ve blogged a lot about this recently as I think about it but it’s always a lot more interesting to see what my colleagues think about it.

Some of my colleagues are, much like me, expecting things to be relatively similar after everything settles down. Books didn’t destroy academia, libraries didn’t remove the need for the lecturer, the tape recorder only goes so far. Yes, things may change, but we expect something familiar to remain. We’ll be able to reach more people because our learning offerings will accommodate more people.

Then there are people who seem to think that meeting student desire immediately means throwing all standards out the window. Somehow, there’s no halfway point between ‘no choice’ and ‘please take a degree as you leave’.

Of course, I’m presenting a straw man to discuss a straw man, but it’s a straw man that looks a lot like some that I’ve seen on campus. People who are designing their courses and systems to deal with the 0.1% of trouble makers rather than the vast majority of willing and able students.

There’s a point at which student desire can’t override our requirement for academic rigour and integrity. Frankly, there are many institutions out there that will sell you a degree but, of course, few people buy them expecting anything from them because everyone knows what kind of institutions they are. It boggles the mind that the few bad apples who show up at an accredited and ethical academy think that, somehow, only they will get the special treatment that they want and institutional quality will persist.

I have to work out what my students need from me and my University – based on what we told them we could do, what we can actually do (which is usually more than that) and what the student has the potential to do (which is usually more than they think they can do, once we’ve made them think about things a bit). There are many things that a student might want us to do, and we’ll have more flexibility for doing that in the future, but what they want isn’t always what they get. Sometimes, you get what you need.

(If you don’t have the Stones in your head right now, it’s time to go and buy some records.)

Your Mission, Should You…

Posted: April 14, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, ALTA, education, educational problem, higher education, improving perception, learning, perception, reflection, teaching Leave a commentThe ALTA meeting of the last two days has been really interesting. My role as an ALTA Fellow has been much better defined after a lot of discussions between the Fellows, the executive and the membership of ALTA. Effectively, if you’re at a University in Australia and reading this, and you’re interested in finding out about what’s going on in our planning for Information and Communications Technology (ICT) Learning and Teaching, contact me and I’ll come out to talk to your school, faculty or University. I’m concentrating on engagement and dissemination – trying to bring the diverse groups in ICT education in Australia (38 organisations, 686 separate ICT-related programs) into a more cohesive group so that we can achieve great things.

To say that this is going to be exciting is an understatement. To omit the words ‘challenging’ and ‘slightly frightening’ would also be an understatement. But I always love a slightly frightening and exciting challenge – that’s why I eat durian.

ICT education in Australia does not have the best image at the moment. That information is already out there. A lot of people have no idea what we even mean by ICT. But let’s be inclusive. It’s Computer Science, Computing, Information Systems, Information Science, Communications Science, Information Technology… everything else where we would be stronger standing together than apart.

There are important questions to be answered. Are we a profession or professions? Are we like engineering (core competencies with school-based variation) or more like science (core concepts and very different disciplines)? How do we improve the way that people see us? How do we make 13 year olds realise that they are suited for our profession – and that our profession is more than typing on a keyboard?

How do we change the world’s perception so that the first picture that people put on an article about computing does not feature someone who is supposed to be perceived as unattractive, socially inept, badly dressed and generally socially unacceptable?

If you are at an Australian University and want to talk about this, get in touch with me. My e-mail address is available by looking for my name at The University of Adelaide – sorry, spambots. If you’re from overseas and would like to offer suggestions or ask questions, our community can be global and, in many respects, it should be global. I learn so much from my brief meetings with overseas experts. As an example, I’ll link you off to Mark Guzdial’s blog here because he’s a good writer, an inspiring academic and educator, and he links to lots of other interesting stuff. I welcome the chance to work with other people whenever I can because, yes, my focus is Australia but my primary focus is “Excellence in ICT education”. That’s a global concern. My dream is that we get so many students interested in this that we look at ways to link up and get synergies for dealing with the vast numbers that we have.

The world is running on computers, generates vast quantities of data, and needs our profession more than ever. Its time to accept the mission and try to raise educational standards, perceptions and expectations across the bar so that ICT Education (or whatever we end up calling it) becomes associated with the terms ‘world-leading’, ‘innovative’, ‘inspiring’ and ‘successful’. And our students don’t have to hide between their brave adoption of semi-pejorative isolating terms or put up with people being proud that they don’t know anything about computers, as if that knowledge is something to be ashamed of.

We need change. Helping to make that happen is now part of my mission. I’m looking for people to help me.

A Dangerous Precedent: Am I Expecting Too Much of My Students?

Posted: April 11, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, education, educational problem, higher education, learning, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches 2 CommentsAnyone with a pulse is aware that there is a lot of discussion at the moment in some important areas of Science. If we scratch the surface of the climate and vaccination debates, we find a roiling frenzy of claim and counter-claim – facts, fallacies and fury all locked in a seething ball. We appear to have reached a point where there is little point in trying to hold a discussion because we have reached a point of dogmatic separation of the parties – where no discussion can bridge the divide. This is the dangerous precedent I’m worried about – not that we have contentious issues, but that we have contentious issues where we build a divide that cannot be bridged by reasonable people with similar backgrounds and training. This is a sad state of affairs, given the degree to which we all observe the same universe.

I don’t teach politics in the classroom and I try not to let my own politics show but I do feel free to discuss good science with my students. Good science is built on good science and, ultimately, begets more good science. Regrettably, a lot of external interest has crept in and it’s easy to see places where good science has been led astray, or published too early, or taken out of context. It’s also easy to see where bad science has crept in under the rug disguised as good science. Sometimes, bad science is just labelled good science and we’re supposed to accept it.

I’m worried that doubt is seen as weakness, when questioning is one of the fundamental starting points for science. I’m worried that a glib (and questionable) certainty is preferred to a complex and multi-valued possibility, even where the latter is correct. I’m worried that reassessment of a theory in light of new evidence is seen as a retrograde step.

I have always said that I expect a lot of my students and that’s true. I tell my research students that will work hard when they’re with me, and that I expect a lot, but that I will work just as hard and that I will try to help them achieve great things. But, along with this, I expect them to be good scientists. I expect them to read a lot across the field and at least be able to make a stab at separating good, replicable results from cherry-picking and interest-influenced studies. That’s really hard, of course, especially when you read things like 47 of the most significant 53 cancer studies can’t be replicated. We can, of course, raise standards to try and address this but, if we’re talking about this in 2012, it’s more than a little embarrassing for the scientific community.

What I try to get across to my students is that, in case of pressure, I expect them to be ethical. I try to convey that a genuine poor (or null) submission is preferable to an excellent piece of plagiarised work, while tracking and encouraging them to try and stay out of that falsely dichotomous zone. But, my goodness, look at the world and look at some of the things we’ve done in the name of Science. Let’s look at some of those in the 20th century with something approaching (semi)informed consent. The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Milgram’s experiment. The Stanford Prison Experiment. I discuss all of these with my students and a number of them think I’m making it up. Until they go looking.

Now, as well as unethical behaviour to contend with, we have divisive behaviour – people trying to split the community for their own purposes. We always had it, of course, but the ease of self-publishing and the speed with which information can be delivered means that it takes days to spread information that used to percolate through doubt filters and peer review. Bad science can often travel faster than good science because it bypasses the peer review process – which has been unfairly portrayed in certain circles as an impediment to innovation or a tool of ‘Big Science’. The appeal to authority is always dangerous, because there is no guarantee that peer review is flawless, but as we have seen with the recent “Faster than the speed of light/ oh, wait, no it’s not” the more appropriately trained eyes you have on your work, the more chance we have of picking up mistakes.

So I expect my students to be well-read, selective, ethical, inclusive and open to constructive criticism as they work towards good or great things.

I still believe that there is a strong and like-minded community out there for them to join – but some days, reading the news, that’s harder to believe than others.

The Student of 2040

Posted: April 10, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, educational problem, higher education, learning, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches 1 CommentOn occasion, I wonder about where students and teachers will be towards the end of my teaching career. Let us be optimistic and say that I’ll still be teaching in 2040 – what will my students look like? (I’m not sure that teaching at that age is considered optimistic but bear with me!)

Right now we’re having to adapt to students who can sit in lectures and, easily and without any effort, look things up on wireless or 3G connections to the Internet – searching taking the role of remembering. Of course, this isn’t (and shouldn’t be) a problem because we’re far more than recitation and memorisation factories. There are many things that Wikipedia can’t do. (Contrary to what at least a few of my students believe!)

But what of the future? What of implanted connections that can map entire processes and skills into the brain? What of video overlays that are invisibly laid over the eye? Very little of what we use today to drive thinking, retrieval, model formation and testing will survive this kind of access.

It would be tempting to think that constant access to the data caucus would remove the need for education but, of course, it only gives you answers to questions that have already been asked and answers that have already been given – a lot of what we do is designed to encourage students to ask questions in new areas and find new answers, including questioning old ones. Much like the smooth page of Wikipedia gives the illusion of a singularity of intent over a sea of chaos and argument, the presence of many answers gives the illusion of no un-answered questions. The constant integration of information into the brain will no more remove the need for education than a library, or the Internet, has already done. In fact, it allows us to focus more on the important matters because it’s easier to see what it is that we actually need to do.

And so, we come back to the fundamentals of our profession – giving students a reason to listen to us, something valuable when they do listen and a strong connection between teaching and the professional world. If I am still teaching by the time I’m in my 70s then I can only hope that I’ve worked out how to do this.