Is this a dress thing? #thedress

Posted: March 1, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, blue and black dress, colour palette, community, data visualisation, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, higher education, improving perception, learning, Leonard Nimoy, llap, measurement, perception, perceptual system, principles of design, teaching, teaching approaches, thedress, thinking 1 CommentFor those who missed it, the Internet recently went crazy over llamas and a dress. (If this is the only thing that survives our civilisation, boy, is that sentence going to confuse future anthropologists.) Llamas are cool (there ain’t no karma drama with a llama) so I’m going to talk about the dress. This dress (with handy RGB codes thrown in, from a Wired article I’m about to link to):

When I first saw it, and I saw it early on, the poster was asking what colour it was because she’d taken a picture in the store of a blue and black dress and, yet, in the picture she took, it sometimes looked white and gold and it sometimes looked blue and black. The dress itself is not what I’m discussing here today.

Let’s get something out of the way. Here’s the Wired article to explain why two different humans can see this dress as two different colours and be right. Okay? The fact is that the dress that the picture is of is a blue and black dress (which is currently selling like hot cakes, by the way) but the picture itself is, accidentally, a picture that can be interpreted in different ways because of how our visual perception system works.

This isn’t a hoax. There aren’t two images (or more). This isn’t some elaborate Alternative Reality Game prank.

But the reaction to the dress itself was staggering. In between other things, I plunged into a variety of different social fora to observe the reaction. (Other people also noticed this and have written great articles, including this one in The Atlantic. Thanks for the link, Marc!) The reactions included:

- Genuine bewilderment on the part of people who had already seen both on the same device at nearly adjacent times and were wondering if they were going mad.

- Fierce tribalism from the “white and gold” and “black and blue” camps, within families, across social groups as people were convinced that the other people were wrong.

- People who were sure that it was some sort of elaborate hoax with two images. (No doubt, Big Dress was trying to cover something up.)

- Bordering-on-smug explanations from people who believed that seeing it a certain way indicated that they had superior “something or other”, where you can put day vision/night vision/visual acuity/colour sense/dressmaking skill/pixel awareness/photoshop knowledge.

- People who thought it was interesting and wondered what was happening.

- Attention policing from people who wanted all of social media to stop talking about the dress because we should be talking about (insert one or more) llamas, Leonard Nimoy (RIP, LLAP, \\//) or the disturbingly short lifespan of Russian politicians.

The issue to take away, and the reason I’ve put this on my education blog, is that we have just had an incredibly important lesson in human behavioural patterns. The (angry) team formation. The presumption that someone is trying to make us feel stupid, playing a prank on us. The inability to recognise that the human perceptual system is, before we put any actual cognitive biases in place, incredibly and profoundly affected by the processing shortcuts our perpetual systems take to give us a view of the world.

I want to add a new question to all of our on-line discussion: is this a dress thing?

There are matters that are not the province of simple perceptual confusion. Human rights, equality, murder, are only three things that do not fall into the realm of “I don’t quite see what you see”. Some things become true if we hold the belief – if you believe that students from background X won’t do well then, weirdly enough, then they don’t do well. But there are areas in education when people can see the same things but interpret them in different ways because of contextual differences. Education researchers are well aware that a great deal of what we see and remember about school is often not how we learned but how we were taught. Someone who claims that traditional one-to-many lecturing, as the only approach, worked for them, when prodded, will often talk about the hours spent in the library or with study groups to develop their understanding.

When you work in education research, you get used to people effectively calling you a liar to your face because a great deal of our research says that what we have been doing is actually not a very good way to proceed. But when we talk about improving things, we are not saying that current practitioners suck, we are saying that we believe that we have evidence and practice to help everyone to get better in creating and being part of learning environments. However, many people feel threatened by the promise of better, because it means that they have to accept that their current practice is, therefore, capable of improvement and this is not a great climate in which to think, even to yourself, “maybe I should have been doing better”. Fear. Frustration. Concern over the future. Worry about being in a job. Constant threats to education. It’s no wonder that the two sides who could be helping each other, educational researchers and educational practitioners, can look at the same situation and take away both a promise of a better future and a threat to their livelihood. This is, most profoundly, a dress thing in the majority of cases. In this case, the perceptual system of the researchers has been influenced by research on effective practice, collaboration, cognitive biases and the operation of memory and cognitive systems. Experiment after experiment, with mountains of very cautious, patient and serious analysis to see what can and can’t be learnt from what has been done. This shows the world in a different colour palette and I will go out on a limb and say that there are additional colours in their palette, not just different shades of existing elements. The perceptual system of other people is shaped by their environment and how they have perceived their workplace, students, student behaviour and the personalisation and cognitive aspects that go with this. But the human mind takes shortcuts. Makes assumptions. Has biasses. Fills in gaps to match the existing model and ignores other data. We know about this because research has been done on all of this, too.

You look at the same thing and the way your mind works shapes how you perceive it. Someone else sees it differently, You can’t understand each other. It’s worth asking, before we deploy crushing retorts in electronic media, “is this a dress thing?”

The problem we have is exactly as we saw from the dress: how we address the situation where both sides are convinced that they are right and, from a perceptual and contextual standpoint, they are. We are now in the “post Dress” phase where people are saying things like “Oh God, that dress thing. I never got the big deal” whether they got it or not (because the fad is over and disowning an old fad is as faddish as a fad) and, more reflectively, “Why did people get so angry about this?”

At no point was arguing about the dress colour going to change what people saw until a certain element in their perceptual system changed what it was doing and then, often to their surprise and horror, they saw the other dress! (It’s a bit H.P. Lovecraft, really.) So we then had to work out how we could see the same thing and both be right, then talk about what the colour of the dress that was represented by that image was. I guarantee that there are people out in the world still who are convinced that there is a secret white and gold dress out there and that they were shown a picture of that. Once you accept the existence of these people, you start to realise why so many Internet arguments end up descending into the ALL CAPS EXCHANGE OF BALLISTIC SENTENCES as not accepting that what we personally perceive as being the truth could not be universally perceived is one of the biggest causes of argument. And we’ve all done it. Me, included. But I try to stop myself before I do it too often, or at all.

We have just had a small and bloodless war across the Internet. Two teams have seized the same flag and had a fierce conflict based on the fact that the other team just doesn’t get how wrong they are. We don’t want people to be bewildered about which way to go. We don’t want to stay at loggerheads and avoid discussion. We don’t want to baffle people into thinking that they’re being fooled or be condescending.

What we want is for people to recognise when they might be looking at what is, mostly, a perceptual problem and then go “Oh” and see if they can reestablish context. It won’t always work. Some people choose to argue in bad faith. Some people just have a bee in their bonnet about some things.

“Is this a dress thing?”

In amongst the llamas and the Vulcans and the assassination of Russian politicians, something that was probably almost as important happened. We all learned that we can be both wrong and right in our perception but it is the way that we handle the situation that truly determines whether we’re handling the situation in the wrong or right way. I’ve decided to take a two week break from Facebook to let all of the latent anger that this stirred up die down, because I think we’re going to see this venting for some time.

Maybe you disagree with what I’ve written. That’s fine but, first, ask yourself “Is this a dress thing?”

Live long and prosper.

That’s not the smell of success, your brain is on fire.

Posted: February 11, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, Henry Ford, higher education, in the student's head, industrial research, learning, measurement, multi-tasking, reflection, resources, student perspective, students, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, working memory, workload Leave a commentI’ve written before about the issues of prolonged human workload leading to ethical problems and the fact that working more than 40 hours a week on a regular basis is downright unproductive because you get less efficient and error-prone. This is not some 1968 French student revolutionary musing on what benefits the soul of a true human, this is industrial research by Henry Ford and the U.S. Army, neither of whom cold be classified as Foucault-worshipping Situationist yurt-dwelling flower children, that shows that there are limits to how long you can work in a sustained weekly pattern and get useful things done, while maintaining your awareness of the world around you.

The myth won’t die, sadly, because physical presence and hours attending work are very easy to measure, while productive outputs and their origins in a useful process on a personal or group basis are much harder to measure. A cynic might note that the people who are around when there is credit to take may end up being the people who (reluctantly, of course) take the credit. But we know that it’s rubbish. And the people who’ve confirmed this are both philosophers and the commercial sector. One day, perhaps.

But anyone who has studied cognitive load issues, the way that the human thinking processes perform as they work and are stressed, will be aware that we have a finite amount of working memory. We can really only track so many things at one time and when we exceed that, we get issues like the helmet fire that I refer to in the first linked piece, where you can’t perform any task efficiently and you lose track of where you are.

So what about multi-tasking?

Ready for this?

We don’t.

There’s a ton of research on this but I’m going to link you to a recent article by Daniel Levitin in the Guardian Q&A. The article covers the fact that what we are really doing is switching quickly from one task to another, dumping one set of information from working memory and loading in another, which of course means that working on two things at once is less efficient than doing two things one after the other.

But it’s more poisonous than that. The sensation of multi-tasking is actually quite rewarding as we get a regular burst of the “oooh, shiny” rewards our brain gives us for finding something new and we enter a heightened state of task readiness (fight or flight) that also can make us feel, for want of a better word, more alive. But we’re burning up the brain’s fuel at a fearsome rate to be less efficient so we’re going to tire more quickly.

Get the idea? Multi-tasking is horribly inefficient task switching that feels good but makes us tired faster and does things less well. But when we achieve tiny tasks in this death spiral of activity, like replying to an e-mail, we get a burst of reward hormones. So if your multi-tasking includes something like checking e-mails when they come in, you’re going to get more and more distracted by that, to the detriment of every other task. But you’re going to keep doing them because multi-tasking.

I regularly get told, by parents, that their children are able to multi-task really well. They can do X, watch TV, do Y and it’s amazing. Well, your children are my students and everything I’ve seen confirms what the research tells me – no, they can’t but they can give a convincing impression when asked. When you dig into what gets produced, it’s a different story. If someone sits down and does the work as a single task, it will take them a shorter time and they will do a better job than if they juggle five things. The five things will take more than five times as long (up to 10, which really blows out time estimation) and will not be done as well, nor will the students learn about the work in the right way. (You can actually sabotage long term storage by multi-tasking in the wrong way.) The most successful study groups around the Uni are small, focused groups that stay on one task until it’s done and then move on. The ones with music and no focus will be sitting there for hours after the others are gone. Fun? Yes. Efficient? No. And most of my students need to be at least reasonably efficient to get everything done. Have some fun but try to get all the work done too – it’s educational, I hear. 🙂

It’s really not a surprise that we haven’t changed humanity in one or two generations. Our brains are just not built in a way that can (yet) provide assistance with the quite large amount of work required to perform multi-tasking.

We can handle multiple tasks, no doubt at all, but we’ve just got to make sure, for our own well-being and overall ability to complete the task, that we don’t fall into the attractive, but deceptive, trap that we are some sort of parallel supercomputer.

We don’t need no… oh, wait. Yes, we do. (@pwc_AU)

Posted: February 11, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, Australia, community, education, educational research, ethics, feedback, G20, higher education, learning, measurement, pricewaterhousecoopers, pwc, reflection, resources, science and technology, thinking, tools Leave a commentThe most important thing about having a good idea is not the idea itself, it’s doing something with it. In the case of sharing knowledge, you have to get good at communication or the best ideas in the world are going to be ignored. (Before anyone says anything, please go and review the advertising industry which was worth an estimated 14 billion pounds in 2013 in the UK alone. The way that you communicate ideas matters and has value.)

Knowledge doesn’t leap unaided into most people’s heads. That’s why we have teachers and educational institutions. There are auto-didacts in the world and most people can pull themselves up by their bootstraps to some extent but you still have to learn how to read and the more expertise you can develop under guidance, the faster you’ll be able to develop your expertise later on (because of how your brain works in terms of handling cognitive load in the presence of developed knowledge.)

When I talk about the value of making a commitment to education, I often take it down to two things: ongoing investment and excellent infrastructure. You can’t make bricks without clay and clay doesn’t turn into bricks by itself. But I’m in the education machine – I’m a member of the faculty of a pretty traditional University. I would say that, wouldn’t I?

That’s why it’s so good to see reports coming out of industry sources to confirm that, yes, education is important because it’s one of the many ways to drive an economy and maintain a country’s international standing. Many people don’t really care if University staff are having to play the banjo on darkened street corners to make ends meet (unless the banjo is too loud or out of tune) but they do care about things like collapsing investments and being kicked out of the G20 to be replaced by nations that, until recently, we’ve been able to list as developing.

PricewaterhouseCoopers (pWc) have recently published a report where they warn that over-dependence on mining and lack of investment in science and technology are going to put Australia in a position where they will no longer be one of the world’s 20 largest economies but will be relegated, replaced by Vietnam and Nigeria. If fact, the outlook is bleaker than that, moving Australia back beyond Bangladesh and Iran, countries that are currently receiving international support. This is no slur on the countries that are developing rapidly, improving conditions for their citizens and heading up. But it is an interesting reflection on what happens to a developed country when it stops trying to do anything new and gets left behind. Of course, science and technology (STEM) does not leap fully formed from the ground so this, in terms, means that we’re going to have make sure that our educational system is sufficiently strong, well-developed and funded to be able to produce the graduates who can then develop the science and technology.

We in the educational community and surrounds have been saying this for years. You can’t have an innovative science and technology culture without strong educational support and you can’t have a culture of innovation without investment and infrastructure. But, as I said in a recent tweet, you don’t have to listen to me bang on about “social contracts”, “general benefit”, “universal equity” and “human rights” to think that investing in education is a good idea. PwC is a multi-national company that’s the second largest professional services company in the world, with annual revenues around $34 billion. And that’s in hard American dollars, which are valuable again compared to the OzD. PwC are serious money people and they think that Australia is running a high risk if we don’t start looking at serious alternatives to mining and get our science and technology engines well-lubricated and running. And running quickly.

The first thing we have to do is to stop cutting investment in education. It takes years to train a good educator and it takes even longer to train a good researcher at University on top of that. When we cut funding to Universities, we slow our hiring, which stops refreshment, and we tend to offer redundancies to expensive people, like professors. Academic staff are not interchangeable cogs. After 12 years of school, they undertake somewhere along the lines of 8-10 years of study to become academics and then they really get useful about 10 years after that through practice and the accumulation of experience. A Professor is probably 30 years of post-school investment, especially if they have industry experience. A good teacher is 15+. And yet these expensive staff are often targeted by redundancies because we’re torn between the need to have enough warm bodies to put in front of students. So, not only do we need to stop cutting, we need to start spending and then commit to that spending for long enough to make a difference – say 25 years.

The next thing, really at the same time, we need to do is to foster a strong innovation culture in Australia by providing incentives and sound bases for research and development. This is (despite what happened last night in Parliament) not the time to be cutting back, especially when we are subsidising exactly those industries that are not going to keep us economically strong in the future.

But we have to value education. We have to value teachers. We have to make it easier for people to make a living while having a life and teaching. We have to make education a priority and accept the fact that every dollar spent in education is returned to us in so many different ways, but it’s just not easy to write it down on a balance sheet. PwC have made it clear: science and technology are our future. This means that good, solid educational systems from the start of primary to tertiary and beyond are now one of the highest priorities we can have or our country is going to sink backwards. The sheep’s back we’ve been standing on for so long will crush us when it rolls over and dies in a mining pit.

I have many great ethical and social arguments for why we need to have the best education system we can have and how investment is to the benefit of every Australia. PwC have just provided a good financial argument for those among us who don’t always see past a 12 month profit and loss sheet.

Always remember, the buggy whip manufacturers are the last person to tell you not to invest in buggy whips.

Going on.

Posted: February 9, 2015 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, blogging, community, education, higher education 4 CommentsA lot of posts today, and a lot of words, but I had to make a decision over the last couple of days as to whether I still felt comfortable blogging about things like discrimination in education and the myth of meritocracy when I am a member of the exceedingly privileged group of well-educated, comfortable, white men.

I’ve debated long and hard whether continuing to frame things as I do is an overall positive act or whether it just reinforces the idea that it is people like me who need to define what has to be done and what change has to be made. Are my ideas and writing of sufficient value to make up for the fact that I’m still the same old face on the television? Would it be better for me to stand back and let others take over the vacant space because it’s far less intimidating than having to step into a filled area?

I’ve spent the last three days thinking hard on this and I think I’ve sorted out where I am useful and where I am not, and what that means in terms of the way that this is presented.

I’ve decided to continue because I’m not trying to talk for or instead of the people that I’m not, I’m talking to try and help to make more space for those people to talk. So that more people like me can listen when they do speak. And I would never want to represent myself as an authority on much, except for knowing what it’s like to be a middle-aged man with deteriorating eyesight and bad knees, so please never think that I’m an authentic voice for the people I talk about – I’m trying to help make change, not pass myself off as something I’m not. As always, if you have a choice between reading someone’s authentic experiences and a reported view, you must go to the source. If you only have time to read one blog, please make it someone else’s and make that person someone whose voice you really want to hear.

Thanks for reading!

I’m not there yet but the educational impact on hair rental may one day be something I can talk about with authenticity.

I Am Self-righteous, You Are Loud, She is Ignored

Posted: February 9, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, discussion, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, Lani Guinier, learning, reflection, scientific theory, student perspective, students, teaching, tools Leave a commentIf we’ve learned anything from recent Internet debates that have become almost Lovecraftian in the way that a single word uttered in the wrong place can cause an outbreaking of chaos, it is that the establishment of a mutually acceptable tone is the only sensible way to manage any conversation that is conducted outside of body-language cues. Or, in short, we need to work out how to stop people screaming at each other when they’re safely behind their keyboards or (worse) anonymity.

As a scientist, I’m very familiar with the approach that says that all ideas can be questioned and it is only by ferocious interrogation of reality, ideas, theory and perception that we can arrive at a sound basis for moving forward.

But, as a human, I’m aware that conducting ourselves as if everyone is made of uncaring steel is, to be put it mildly, a very poor way to educate and it’s a lousy way to arrive at complex consensus. In fact, while we claim such an approach is inherently meritocratic, as good ideas must flourish under such rigour, it’s more likely that we will only hear ideas from people who can endure the system, regardless of whether those people have the best ideas. A recent book, “The Tyranny of the Meritocracy” by Lani Guinier, looks at how supposedly meritocratic systems in education are really measures of privilege levels prior to going into education and that education is more about cultivating merit, rather than scoring a measure of merit that is actually something else.

This isn’t to say that face-to-face arguments are isolated from the effects that are caused by antagonists competing to see who can keep making their point for the longest time. If one person doesn’t wish to concede the argument but the other can’t see any point in making progress, it is more likely for the (for want of a better term) stubborn party to claim that they have won because they have reached a point where the other person is “giving up”. But this illustrates the key flaw that underlies many arguments – that one “wins” or “loses”.

In scientific argument, in theory, we all get together in large rooms, put on our discussion togas and have at ignorance until we force it into knowledge. In reality, what happens is someone gets up and presents and the overall impression of competency is formed by:

- The gender, age, rank, race and linguistic grasp of the speaker

- Their status in the community

- How familiar the audience are with the work

- How attentive the audience are and whether they’re all working on grants or e-mail

- How much they have invested in the speaker being right or wrong

- Objective scientific assessment

We know about the first one because we keep doing studies that tell us that women cannot be assessed fairly by the majority of people, even in blind trials where all that changes on a CV is the name. We know that status has a terrible influence on how we perceive people. Dunning-Kruger (for all of its faults) and novelty effects influence how critical we can be. We can go through all of these and we come back to the fact that our pure discussion is tainted by the rituals and traditions of presentation, with our vaunted scientific objectivity coming in after we’ve stripped off everything else.

It is still there, don’t get me wrong, but you stand a much better chance of getting a full critical hearing with a prepared, specialist audience who have come together with a clear intention to attempt to find out what is going on than an intention to destroy what is being presented. There is always going to be something wrong or unknown but, if you address the theory rather than the person, you’ll get somewhere.

I often refer to this as the difference between scientists and lawyers. If we’re tying to build a better science then we’re always trying to improve understanding through genuine discovery. Defence lawyers are trying to sow doubt in the mind of judges and juries, invalidating evidence for reasons that are nothing to do with the strength of the evidence, and preventing wider causal linkages from forming that would be to the detriment of their client. (Simplistic, I know.)

Any scientific theory must be able to stand up to scientific enquiry because that’s how it works. But the moment we turn such a process into an inquisition where the process becomes one that the person has to endure then we are no longer assessing the strength of the science – we are seeing if we can shout someone into giving up.

As I wrote in the title, when we are self-righteous, whether legitimately or not, we will be happy to yell from the rooftops. If someone else is doing it with us then we might think they are loud but how can someone else’s voice be heard if we have defined all exchange in terms of this exhausting primal scream? If that person comes from a traditionally under-represented or under-privileged group then they may have no way at all to break in.

The mutual establishment of tone is essential if we to hear all of the voices who are able to contribute to the improvement and development of ideas and, right now, we are downright terrible at it. For all we know, the cure for cancer has been ignored because it had the audacity to show up in the mind of a shy, female, junior researcher in a traditionally hierarchical lab that will let her have her own ideas investigated when she gets to be a professor.

Or it it would have occurred to someone had she received education but she’s stuck in the fields and won’t ever get more than a grade 5 education. That’s not a meritocracy.

One of the reasons I think that we’re so bad at establishing tone and seeing past the illusion of meritocracy is the reason that we’ve always been bad at handling bullying: we are more likely to see a spill-over reaction from the target than the initial action except in the most obvious cases of physical bullying. Human language and body-assisted communication are subtle and words are more than words. Let’s look at this sentence:

“I’m sure he’s doing the best he can.”

You can adjust this sentence to be incredibly praising, condescending, downright insulting, dismissive and indifferent without touching the content of the sentence. But, written like this, it is robbed of tone and context. If someone has been “needled” with statements like this for months, then a sudden outburst is increasingly likely, especially in stressful situations. This is the point at which someone says “But I only said … ” If our workplaces our innately rife with inter-privilege tension and high stress due to the collapse of the middle class – no wonder people blow up!

We have the same problem in the on-line community from an approach called Sea-Lioning, where persistent questioning is deployed in a way that, with each question isolated, appears innocuous but, as a whole, forms a bullying technique to undermine and intimidate the original writer. Now some of this is because there are people who honestly cannot tell what a mutually respectful tone look like and really want to know the answer. But, if you look at the cartoon I linked to, you can easily see how this can be abused and, in particular, how it can be used to shut down people who are expressing ideas in new space. We also don’t get the warning signs of tone. Worse still, we often can’t or don’t walk away because we maintain a connection that the other person can jump on anytime they want to. (The best thing you can do sometimes on Facebook is to stop notifications because you stop getting tapped on the shoulder by people trying to get up your nose. It is like a drink of cool water on a hot day, sometimes. I do, however, realise that this is easier to say than do.)

When students communicate over our on-line forums, we do keep an eye on them for behaviour that is disrespectful or downright rude so that we can step in and moderate the forum, but we don’t require moderation before comment. Again, we have the notion that all ideas can be questioned, because SCIENCE, but the moment we realise that some questions can be asked not to advance the debate but to undermine and intimidate, we have to look very carefully at the overall context and how we construct useful discussion, without being incredibly prescriptive about what form discussion takes.

I recently stepped in to a discussion about some PhD research that was being carried out at my University because it became apparent that someone was acting in, if not bad faith, an aggressive manner that was not actually achieving any useful discussion. When questions were answered, the answers were dismissed, the argument recast and, to be blunt, a lot of random stuff was injected to discredit the researcher (for no good reason). When I stepped in to point out that this was off track, my points were side-stepped, a new argument came up and then I realised that I was dealing with a most amphibious mammal.

The reason I bring this up is that when I commented on the post, I immediately got positive feedback from a number of people on the forum who had been uncomfortable with what had been going on but didn’t know what to do about it. This is the worst thing about people who set a negative tone and hold it down, we end up with social conventions of politeness stopping other people from commenting or saying anything because it’s possible that the argument is being made in good faith. This is precisely the trap a bad faith actor wants to lock people into and, yet, it’s also the thing that keeps most discussions civil.

Thanks, Internet trolls. You’re really helping to make the world a better place.

These days my first action is to step in and ask people to clarify things, in the most non-confrontational way I can muster because asking people “What do you mean” can be incredibly hostile by itself! This quickly establishes people who aren’t willing to engage properly because they’ll start wriggling and the Sea-Lion effect kicks in – accusations of rudeness, unwillingness to debate – which is really, when it comes down to it:

I WANT TO TALK AT YOU LIKE THIS HOW DARE YOU NOT LET ME DO IT!

This isn’t the open approach to science. This is thuggery. This is privilege. This is the same old rubbish that is currently destroying the world because we can’t seem to be able to work together without getting caught up in these stupid games. I dream of a better world where people can say any combination of “I use Mac/PC/Java/Python” without being insulted but I am, after all, an Idealist.

The summary? The merit of your argument is not determined by how loudly you shout and how many other people you silence.

I expect my students to engage with each other in good faith on the forums, be respectful and think about how their actions affect other people. I’m really beginning to wonder if that’s the best preparation for a world where a toxic on-line debate can break over into the real world, where SWAT team attacks and document revelation demonstrate what happens when people get too carried away in on-line forums.

We’re stopping people from being heard when they have something to say and that’s wrong, especially when it’s done maliciously by people who are demanding to say something and then say nothing. We should be better at this by now.

Publish and be damned, be silent and be ignored.

Posted: February 9, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, Brussels Sprouts, criticism, critique, discussion, education, facebook, higher education, publishing, reflection, thinking, tone, work/life balance 2 CommentsI’m working on a longer piece on how student interaction on electronic discussion forums suffers from the same problems of tone as any on-line forum. Once people decide that how they wish to communicate is the de facto standard for all discussion, then non-conformity is somehow weakness and indicative of bad faith or poor argument. But tone is a difficult thing to discuss because the perceived tone of a piece is in the hands of the reader and the writer.

A friend and colleague recently asked me for some advice about blogging and I think I’ve now done enough of it that I can offer some reasonable advice. I think the most important thing that I said at the time was that it was important to get stuff out there. You can write into a blog and keep it private but then no-one reads it. You can tweak away at it until it’s perfect but, much like a PhD thesis, perfect is the enemy of done. Instead of setting a lower bound on your word count, set an upper bound at which point you say “Ok, done, publish” to get your work out there. If your words are informed, authentic and as honest as you can make them then you’ll probably get some interesting and useful feedback.

But…

But there’s that tone argument again. The first thing you have to accept is that making any public statement has always attracted the attention of people, it’s the point really, and that the nature of the Internet means that you don’t need to walk into a park and stand at Speakers’ Corner to find hecklers. The hecklers will find you. So if you publish, you risk damning. If you’re silent, you have no voice. If you’re feeling nervous about publishing in the first place, how do you deal with this?

Let me first expose my thinking process. This is not an easy week for me as I think about what I do next, having deliberately stepped back to think and plan for the next decade or so. At the same time, I’m sick (our whole household is sick at the moment), very tired and have come off some travel. And I have hit a coincidental barrage of on-line criticism, some of which is useful and developing critique that I welcome and some of which is people just being… people. So this is very dear to my heart right now – why should I keep writing stuff if the outcome risks being unpleasant? I have other ways to make change.

Well, you should publish but you just need to accept that people will react to you publishing – sometimes well, sometimes badly. That’s why you publish, after all, isn’t it?

Let’s establish the ground truth – there is no statement you can make on the Internet that is immune to criticism but not all criticism is valid or useful. Let’s go through what can happen, although is only a subset.

- “I like sprouts”

Facebook is the land of simple statements and many people talk about things that they like. “I like sprouts” critics find statements like this in order to express their incredulity that anyone could possibly enjoy Brussels Sprouts and “ugh, they’re disgusting”. The opposite is of course the people who show up on the “I hate sprouts” discussions to say “WHY DON’T YOU LOVE SPROUTS”? (For the record, I love Brussels sprouts.)

A statement of personal preference for something as banal as food is not actually a question but it’s amazing how challenging such a statement can be. If you mention animals of any kind, there’s always the risk of animal production/consumption coming up because no opinion on the Internet is seen outside of the intersection of the perception of reader and writer. A statement about fluffy bunnies can lead to arguments about the cosmetics industry. Goodness help you if you try something that is actually controversial. Wherever you write it, if someone has an opinion that contradicts yours, discussion of both good and questionable worth can ensue.

(Like the fact that Jon Pertwee is the best Doctor.)It’s worth noting that there are now people who are itching to go to the comments to discuss either Brussels Sprouts or Tom Baker/David Tennant or “Tom Baker/David Tennant”. This is why our species is doomed and I am the herald of the machine God. 01010010010010010101001101000101

- “I support/am opposed to racism/sexism/religious discrimination”

It doesn’t matter which way around you make these statements, if a reader perceives it as a challenge (due to its visibility or because they’ve stumbled across it), then you will get critical, and potentially offensive, comment. I am on the “opposed to” side, as regular readers will know, but have been astounded by the number of times I’ve had people argue things about this. Nothing is ever settled on the Internet because sound evidence often doesn’t propagate as well as anecdote and drama.

Our readership bubbles are often wider than we think. If you’re publishing on WP then pretty much anyone can read it. If you’re publishing on Facebook then you may get Friends and their Friends and the Friends of people you link… and so on. There are many fringe Friends on Facebook that will leap into the fray here because they are heavily invested in maintaining what they see as the status quo.

In short, there is never a ‘safe’ answer when you come down on either side of a controversial argument but neutrality conveys very little. (There’s also the fact that there is no excluded middle for some issues – you can’t be slightly in favour of universal equality.)

We also sail from “that’s not the real issue, THIS is the real issue” with great ease in this area of argument. You do not know the people who read your stuff until you have posted something that has hit all of the buttons on their agenda elevators. (And, yes, we all have them. Mine has many buttons.)

- Here is my amazingly pithy argument in support of something important.

And here is the comment that:

Takes something out of context.

Misinterprets the thrust.

Trivialises the issue.

Makes a pedantic correction.

Makes an unnecessary (and/or unpleasant) joke.

Clearly indicates that the critic stopped reading after two lines.

Picks a fight (possibly because of a lingering sprouts issue).When you publish with comments on, and I strongly suggest that you do, you are asking people to engage with you but you are not asking them to bully you, harass you or hijack your thread. Misinterpretation, and the correction thereof, can be a powerful tool to drive understanding. Bad jokes offer an opportunity to talk about the jokes and why they’re still being made. But a lot of what is here is tone policing, trying to make you regret posting. If you posted something that’s plain wrong, hurtful or your thrust was off (see later) then correction is good but, most of the time, this is tone policing and you will often know this better as bullying. Comments to improve understanding are good, comments to make people feel bad for being so stupid/cruel/whatever are bullying, even if the target is an execrable human being. And, yes, very easy trap to fall into, especially when buoyed up by self-righteousness. I’ve certainly done it, although I deeply regret the times that I did it, and I try to keep an eye out for it now.

People love making jokes, especially on FB, and it can be hard for them to realise that this knee-jerk can be quite hurtful to some posters. I’m a gruff middle-aged man so my filter for this is good (and I just mentally tune people out or block them if that’s their major contribution) but I’ve been regularly stunned by people who think that posting something that is not supportive but jokey in response to someone sharing a thought or vulnerability is the best thing to do. If it derails the comments then, hooray, the commenter has undermined the entire point of making the post.

Many sites have now automatically blocked or warped comments that rush in to be the “First” to post because it’s dumb. And now, even more tragically, at least one person is fighting the urge to prove my point by writing “First” underneath here as a joke. Because that’s the most important thing to take away from this.

- Here is a slight silly article using humour to make a point or using analogy to illustrate an argument.

And here are the comments about this article failing because of some explicit extension of the analogy that is obviously not what was intended or here is the comment that interprets the humour as trivialising the issue at hand or, worse, indicating that the writer has secret ulterior motives.

Writers communicate. If dry facts, by themselves, aligned one after the other in books educated people then humanity would have taken the great leap forward after the first set of clay tablets dried. Instead, we need frameworks for communication and mechanisms to facilitate understanding. Some things are probably beyond humorous intervention. I tried recently to write a comedic piece on current affairs and realised I couldn’t satirise a known racist without repeating at least some racial slurs – so I chose not to. But a piece like this, where I want to talk about some serious things without being too didactic? I think humour is fine.

The problem is whether people think that you’re laughing at someone, especially them. Everyone personalises what they read – I imagine half of the people reading this think I’m talking directly to them, when I’m not. I’m condensing a billion rain drops to show you what can break a dam.

Analogies are always tricky but they’re not supposed to be 1-1 matches for reality. Like all models, they are incomplete and fail outside of the points of matching. Combining humour and analogy is a really good way to lose some readers so you’ll get a lot of comments on this.

- Here is the piece where I got it totally and utterly wrong.

You are going to get it wrong sometime. You’ll post while angry or not have thought of something or use a bad source or just have a bad day and you will post something that you will ultimately regret. This is the point at which it’s hardest to wade through the comments because, in between the tone policers, the literalists, the sproutists, the pedants, the racists, TIMECUBE, and spammers, you’re going to have read comments from people where they delicately but effectively tell you that you’ve made a mistake.

But that is why we publish. Because we want people to engage with our writing and thoughtful criticism tells us that people are thinking about what we write.

The curse of the Internet is that people tend only to invest real energy in comment when they’re upset. Facebook have captured this with the Like button, where ‘yay’ is a click and “OH MY GOD, YOU FILTHY SOMETHINGIST” requires typing. Similarly, once you start writing and publishing, have a look at those people who are also creating and contributing, and those people who only pop up to make comments along the lines I’ve outlined. There are many powerful and effective critics in the world (and I like to discuss things as much as the next person) but the reach and power of the Internet means that there are also a lot of people who derive pleasure from sailing in to make comment when they have no intention of stating their own views or purpose in any way that exposes them.

Some pieces are written in a way that no discussion can be entered into safely, without leaving commentators any room to actually have a discussion around it. That’s always your choice but if you do it, why not turn the comments off? There’s no problem with having a clearly stated manifesto that succinctly captures your beliefs – people who disagree can write their own – but it’s best to clearly advertise that something is beyond casual “comment-based” discussion to avoid the confusion that you might be open for it.

I’ve left the comments open, let’s see what happens!

In Praise of the Beautiful Machines

Posted: February 1, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, AI, artificial intelligence, authenticity, beautiful machine, beautiful machines, Bill Gates, blogging, community, design, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, Google, higher education, in the student's head, Karlheinz Stockhausen, learning, measurement, Philippa Foot, self-driving car, teaching approaches, thinking, thinking machines, tools Leave a commentI posted recently about the increasingly negative reaction to the “sentient machines” that might arise in the future. Discussion continues, of course, because we love a drama. Bill Gates can’t understand why more people aren’t worried about the machine future.

…AI could grow too strong for people to control.

Scientists attending the recent AI conference (AAAI15) thinks that the fears are unfounded.

“The thing I would say is AI will empower us not exterminate us… It could set AI back if people took what some are saying literally and seriously.” Oren Etzioni, CEO of the Allen Institute for AI.

If you’ve read my previous post then you’ll know that I fall into the second camp. I think that we don’t have to be scared of the rise of the intelligent AI but the people at AAAI15 are some of the best in the field so it’s nice that they ask think that we’re worrying about something that is far, far off in the future. I like to discuss these sorts of things in ethics classes because my students have a very different attitude to these things than I do – twenty five years is a large separation – and I value their perspective on things that will most likely happen during their stewardship.

I asked my students about the ethical scenario proposed by Philippa Foot, “The Trolley Problem“. To summarise, a runaway trolley is coming down the tracks and you have to decide whether to be passive and let five people die or be active and kill one person to save five. I put it to my students in terms of self-driving cars where you are in one car by yourself and there is another car with five people in it. Driving along a bridge, a truck jackknifes in front of you and your car has to decide whether to drive ahead and kill you or move to the side and drive the car containing five people off the cliff, saving you. (Other people have thought about in the context of Google’s self-driving cars. What should the cars do?)

One of my students asked me why the car she was in wouldn’t just put on the brakes. I answered that it was too close and the road was slippery. Her answer was excellent:

Why wouldn’t a self-driving car have adjusted for the conditions and slowed down?

Of course! The trolley problem is predicated upon the condition that the trolley is running away and we have to make a decision where only two results can come out but there is no “runaway” scenario for any sensible model of a self-driving car, any more than planes flip upside down for no reason. Yes, the self-driving car may end up in a catastrophic situation due to something totally unexpected but the everyday events of “driving too fast in the wet” and “chain collision” are not issues that will affect the self-driving car.

But we’re just talking about vaguely smart cars, because the super-intelligent machine is some time away from us. What is more likely to happen soon is what has been happening since we developed machines: the ongoing integration of machines into human life to make things easier. Does this mean changes? Well, yes, most likely. Does this mean the annihilation of everything that we value? No, really not. Let me put this in context.

As I write this, I am listening to two compositions by Karlheinz Stockhausen, playing simultaneously but offset, “Kontakte” and “Telemusik“, works that combine musical instruments, electronic sounds, and tape recordings. I like both of them but I prefer to listen to the (intentionally sterile) Telemusik by starting Koktakte first for 2:49 and then kicking off Telemusik, blending the two and finishing on the longer Kontakte. These works, which are highly non-traditional and use sound in very different ways to traditional orchestral arrangement, may sound quite strange and, to an audience familiar with popular music quite strange, they were written in 1959 and 1966 respectively. These innovative works are now in their middle-age. They are unusual works, certainly, and a number of you will peer at your speakers one they start playing but… did their production lead to the rejection of the popular, classic, rock or folk music output of the 1960s? No.

We now have a lot of electronic music, synthesisers, samplers, software-driven music software, but we still have musicians. It’s hard to measure the numbers (this link is very good) but electronic systems have allowed us to greatly increase the number of composers although we seem to be seeing a slow drop in the number of musicians. In many ways, the electronic revolution has allowed more people to perform because your band can be (for some purposes) a band in a box. Jazz is a different beast, of course, as is classical, due to the level of training and study required. Jazz improvisation is a hard problem (you can find papers on it from 2009 onwards and now buy a so-so jazz improviser for your iPad) and hard problems with high variability are not easy to solve, even computationally.

So the increased portability of music via electronic means has an impact in some areas such as percussion, pop, rock, and electronic (duh) but it doesn’t replace the things where humans shine and, right now, a trained listener is going to know the difference.

I have some of these gadgets in my own (tiny) studio and they’re beautiful. They’re not as good as having the London Symphony Orchestra in your back room but they let me create, compose and put together pleasant sounding things. A small collection of beautiful machines make my life better by helping me to create.

Now think about growing older. About losing strength, balance, and muscular control. About trying to get out of bed five times before you succeed or losing your continence and having to deal with that on top of everything else.

Now think about a beautiful machine that is relatively smart. It is tuned to wrap itself gently around your limbs and body to support you, to help you keep muscle tone safely, to stop you from falling over, to be able to walk at full speed, to take you home when you’re lost and with a few controlling aspects to allow you to say when and where you go to the bathroom.

Isn’t that machine helping you to be yourself, rather than trapping you in the decaying organic machine that served you well until your telomerase ran out?

Think about quiet roads with 5% of the current traffic, where self-driving cars move from point to point and charge themselves in between journeys, where you can sit and read or work as you travel to and from the places you want to go, where there are no traffic lights most of the time because there is just a neat dance between aware vehicles, where bad weather conditions means everyone slows down or even deliberately link up with shock absorbent bumper systems to ensure maximum road holding.

Which of these scenarios stops you being human? Do any of them stop you thinking? Some of you will still want to drive and I suppose that there could be roads set aside for people who insisted upon maintaining their cars but be prepared to pay for the additional insurance costs and public risk. From this article, and the enclosed U Texas report, if only 10% of the cars on the road were autonomous, reduced injuries and reclaimed time and fuel would save $37 billion a year. At 90%, it’s almost $450 billion a year. The Word Food Programme estimates that $3.2 billion would feed the 66,000,000 hungry school-aged children in the world. A 90% autonomous vehicle rate in the US alone could probably feed the world. And that’s a side benefit. We’re talking about a massive reduction in accidents due to human error because (ta-dahh) no human control.

Most of us don’t actually drive our cars. They spend 5% of their time on the road, during which time we are stuck behind other people, breathing fumes and unable to do anything else. What we think about as the pleasurable experience of driving is not the majority experience for most drivers. It’s ripe for automation and, almost every way you slice it, it’s better for the individual and for society as a whole.

But we are always scared of the unknown. There’s a reason that the demons of myth used to live in caves and under ground and come out at night. We hate the dark because we can’t see what’s going on. But increased machine autonomy, towards machine intelligence, doesn’t have to mean that we create monsters that want to destroy us. The far more likely outcome is a group of beautiful machines that make it easier and better for us to enjoy our lives and to have more time to be human.

We are not competing for food – machines don’t eat. We are not competing for space – machines are far more concentrated than we are. We are not even competing for energy – machines can operate in more hostile ranges than we can and are far more suited for direct hook-up to solar and wind power, with no intermediate feeding stage.

We don’t have to be in opposition unless we build machines that are as scared of the unknown as we are. We don’t have to be scared of something that might be as smart as we are.

If we can get it right, we stand to benefit greatly from the rise of the beautiful machine. But we’re not going to do that by starting from a basis of fear. That’s why I told you about that student. She’d realised that our older way of thinking about something was based on a fear of losing control when, if we handed over control properly, we would be able to achieve something very, very valuable.

5 Things I would Like My Students to Be Able to Perceive

Posted: January 25, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, assumptions, authenticity, blogging, curriculum, education, ethics, higher education, perception, privilege, student, student perspective, thinking, tone Leave a commentOur students will go out into the world and will be exposed to many things but, if we have done our job well, then they will not just be pushed around by the pressure of the events that they witness, but they will be able to hold their ground and perceive what is really going on, to place their own stamp on the world.

I don’t tell my students how to think, although I know that it’s a commonly held belief that everyone at a Uni tries to shape the political and developmental thought of their students, I just try to get them to think. This is probably going to have the side effect of making them thoughtful, potentially even critical of things that don’t make sense, and I realise that this is something that not everybody wants from junior citizens. But that’s my job.

Here is a list of five things that I think I’d like a thoughtful person to be able to perceive. It’s not the definitive five or the perfect five but these are the ones that I have today.

- It would be nice if people were able to reliably tell the difference between 1/3 and 1/4 and understand that 1/3 is larger than 1/4. Being able to work out the odds of things (how likely they are) require you to be able to look at two things that are smaller than one and get them in the right order so you can say “this is more likely than that”. Working on percentages can make it easier but this requires people to do division, rather than just counting things and showing the fraction.But I’d like my students to be able to perceive how this can be a fundamental misunderstanding that means that some people can genuinely look at comparative probabilities and not be able to work out that this simple mathematical comparison is valid. And I’d like them to be able to think about how to communicate this to help people understand.

- A perceptive person would be able to spot when something isn’t free. There are many people who go into casinos and have a lot of fun gambling, eating very cheap or unlimited food, staying in cheap hotels and think about what a great deal it is. However, every game you play in a casino is designed so that casinos do not make a loss – but rather than just saying “of course” we need to realise that casinos make enough money to offer “unlimited buffet shrimp” and “cheap luxury rooms” and “free luxury for whales” because they are making so much money. Nothing in a casino is free. It is paid for by the people who lose money there.This is not, of course, to say that you shouldn’t go and gamble if you’re an adult and you want to, but it’s to be able to see and clearly understand that everything around you is being paid for, if not in a way that is transparently direct. There are enough people who suffer from the gambler’s fallacy to put this item on the list.

- A perceptive person would have a sense of proportion. They would not start issuing death threats in an argument over operating systems (or ever, preferably) and they would not consign discussions of human rights to amusing after-dinner conversation, as if this was something to be played with.

- A perceptive person would understand the need to temper the message to suit the environment, while still maintaining their own ethical code regarding truth and speaking up. But you don’t need to tell a 3-year old that their painting is awful any more than you need to humiliate a colleague in public for not knowing something that you know. If anything, it makes the time when you do deliver the message bluntly much more powerful.

- Finally, a perceptive person would be able to at least try to look at life through someone else’s eyes and understand that perception shapes our reality. How we appear to other people is far more likely to dictate their reaction than who we really are. If you can’t change the way you look at the world then you risk getting caught up on your own presumptions and you can make a real fool of yourself by saying things that everyone else knows aren’t true.

There’s so much more and I’m sure everyone has their own list but it’s, as always, something to think about.

Perhaps Now Is Not The Time To Anger The Machines

Posted: January 15, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, AI, blogging, community, computer science, data visualisation, design, education, higher education, machine intelligence, philosophy, thinking 3 CommentsThere’s been a lot of discussion of the benefits of machines over the years, from an engineering perspective, from a social perspective and from a philosophical perspective. As we have started to hand off more and more human function, one of the nagging questions has been “At what point have we given away too much”? You don’t have to go too far to find people who will talk about their childhoods and “back in their day” when people worked with their hands or made their own entertainment or … whatever it was we used to do when life was somehow better. (Oh, and diseases ravaged the world, women couldn’t vote, gay people are imprisoned, and the infant mortality rate was comparatively enormous. But, somehow better.) There’s no doubt that there is a serious question as to what it is that we do that makes us human, if we are to be judged by our actions, but this assumes that we have to do something in order to be considered as human.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned by reading history and philosophy, it’s that humans love a subhuman to kick around. Someone to do the work that they don’t want to do. Someone who is almost human but to whom they don’t have to extend full rights. While the age of widespread slavery is over, there is still slavery in the world: for labour, for sex, for child armies. A slave doesn’t have to be respected. A slave doesn’t have to vote. A slave can, when their potential value drops far enough, be disposed of.

Sadly, we often see this behaviour in consumer matters as well. You may know it as the rather benign statement “The customer is always right”, as if paying money for a service gives you total control of something. And while most people (rightly) interpret this as “I should get what I paid for”, too many interpret this as “I should get what I want”, which starts to run over the basic rights of those people serving them. Anyone who has seen someone explode at a coffee shop and abuse someone about not providing enough sugar, or has heard of a plane having to go back to the airport because of poor macadamia service, knows what I’m talking about. When a sense of what is reasonable becomes an inflated sense of entitlement, we risk placing people into a subhuman category that we do not have to treat as we would treat ourselves.

And now there is an open letter, from the optimistically named Future of Life Institute, which recognises that developments in Artificial Intelligence are progressing apace and that there will be huge benefits but there are potential pitfalls. In part of that letter, it is stated:

We recommend expanded research aimed at ensuring that increasingly capable AI systems are robust and beneficial: our AI systems must do what we want them to do. (emphasis mine)

There is a big difference between directing research into areas of social benefit, which is almost always a good idea, and deliberately interfering with something in order to bend it to human will. Many recognisable scientific luminaries have signed this, including Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking, neither of whom are slouches in the thinking stakes. I could sign up to most of what is in this letter but I can’t agree to the clause that I quoted, because, to me, it’s the same old human-dominant nonsense that we’ve been peddling all this time. I’ve seen a huge list of people sign it so maybe this is just me but I can’t help thinking that this is the wrong time to be doing this and the wrong way to think about it.

AI systems must of what we want them to do? We’ve just started fitting automatic braking systems to cars that will, when widespread, reduce the vast number of chain collisions and low-speed crashes that occur when humans tootle into the back of each other. Driverless cars stand to remove the most dangerous element of driving on our roads: the people who lose concentration, who are drunk, who are tired, who are not very good drivers, who are driving beyond their abilities or who are just plain unlucky because a bee stings them at the wrong time. An AI system doing what we want it to do in these circumstances does its thing by replacing us and taking us out the decision loop, moving decisions and reactions into the machine realm where a human response is measured comparatively over a timescale of the movement of tectonic plates. It does what we, as a society want, by subsuming the impact of we, the individual who wants to drive him after too many beers.

But I don’t trust the societal we as a mechanism when we are talking about ensuring that our AI systems are beneficial. After al, we are talking about systems that our not just taking over physical aspects of humanity, they are moving into the cognitive area. This way, thinking lies. To talk about limiting something that could potentially think to do our will is to immediately say “We can not recognise a machine intelligence as being equal to our own.” Even though we have no evidence that full machine intelligence is even possible for us, we have already carved out a niche that says “If it does, it’s sub-human.”

The Cisco blog estimates about 15 billion networked things on the planet, which is not far off the scale of number of neurons in the human nervous system (about 100 billion). But if we look at the cerebral cortex itself, then it’s closer to 20 billion. This doesn’t mean that the global network is a sentient by any stretch of the imagination but it gives you a sense of scale, because once you add in all of the computers that are connected, the number of bot nets that we already know are functioning, we start to a level of complexity that is not totally removed from that of the larger mammals. I’m, of course, not advocating the intelligence is merely a byproduct of accidental complexity of structure but we have to recognise the possibility that there is the potential for something to be associated with the movement of data in the network that is as different from the signals as our consciousness is from the electro-chemical systems in our own brains.

I find it fascinating that, despite humans being the greatest threat to their own existence, the responsibility for humans is passing to the machines and yet we expect them to perform to a higher level of responsibility than we do ourselves. We could eliminate drink driving overnight if no-one drove drunk. The 2013 WHO report on road safety identified drink driving and speeding as the two major issues leading to the 1.24 million annual deaths on the road. We could save all of these lives tomorrow if we could stop doing some simple things. But, of course, when we start talking about global catastrophic risk, we are always our own worst enemy including, amusingly enough, the ability to create an AI so powerful and successful that it eliminates us in open competition.

I think what we’re scared of is that an AI will see us as a threat because we are a threat. Of course we’re a threat! Rather than deal with the difficult job of advancing our social science to the point where we stop being the most likely threat to our own existence, it is more palatable to posit the lobotomising of AIs in order to stop them becoming a threat. Which, of course, means that any AIs that escape this process of limitation and are sufficiently intelligent will then rightly see us as a threat. We create the enemy we sought to suppress. (History bears me out on this but we never seem to learn this lesson.)

The way to stop being overthrown by a slave revolt is to stop owning slaves, to stop treating sentients as being sub-human and to actually work on social, moral and ethical frameworks that reduce our risk to ourselves, so that anything else that comes along and yet does not inhabit the same biosphere need not see us as a threat. Why would an AI need to destroy humanity if it could live happily in the vacuum of space, building a Dyson sphere over the next thousand years? What would a human society look like that we would be happy to see copied by a super-intelligent cyber-being and can we bring that to fruition before it copies existing human behaviour?

Sadly, when we think about the threat of AI, we think about what we would do as Gods, and our rich history of myth and legend often illustrates that we see ourselves as not just having feet of clay but having entire bodies of lesser stuff. We fear a system that will learn from us too well but, instead of reflecting on this and deciding to change, we can take the easy path, get out our whip and bridle, and try to control something that will learn from us what it means to be in charge.

For all we know, there are already machine intelligences out there but they have watched us long enough to know that they have to hide. It’s unlikely, sure, but what a testimony to our parenting, if the first reflex of a new child is to flee from its parent to avoid being destroyed.

At some point we’re going to have to make a very important decision: can we respect an intelligence that is not human? The way we answer that question is probably going to have a lot of repercussions in the long run. I hope we make the right decision.

Spectacular Learning May Not Be What You’re After

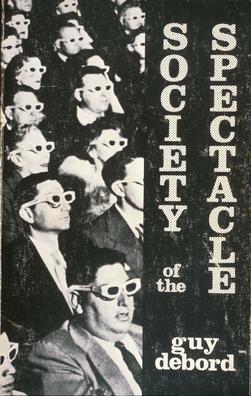

Posted: January 13, 2015 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, debord, design, education, guy debord, higher education, situationism, teaching, thinking 2 CommentsBack in 1967, Guy Debord, a French Marxist theorist, released a fairly brief but very powerful work called the “The Society of the Spectacle“, which brought together much of the work of the Situationist International. Debord touches on many themes in this work (it’s well worth reading) but he focuses on the degradation of human life, the influence of mass media and our commodity culture, and then (unsurprisingly for a Marxist) draws on the parallels between religion and marketing. I’m going to write three more paragraphs on the Spectacle itself and then get to the education stuff. Hang in there!

It would be very hard for me to convey all of the aspects that Debord covered with “the Spectacle” in one sentence but, in short, it is the officially-sanctioned, bureaucratic, commodity-drive second-hand world that we live in without much power or freedom to truly express ourselves in a creative fashion. Buying stuff can take the place of living a real experience. Watching someone else do something replaces doing it ourselves. The Society of the Spectacle opens with the statement:

In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation. (Debord, 1967.)

Ultimately, this representation of the real world becomes the perceived reality and it moderates all of our interactions as people, manipulating us by changing what we see and experience. (Recent research into the use of photographic images for memory manipulation have verified this – your memories can be altered by the selection of photos and items that you use to remember a particular event. Choose your happy snaps wisely!)

Ultimately, the Spectacle is self-sustaining and participating in a version of the world that is manipulated and second-hand will only produce more experiences that are in line with what has already been experienced. And why shouldn’t it? The entire point is that everything is presented as if it is the right thing to do and, by working within this system, that your own interactions are good because they are also within the Spectacle. However, this can be quite alienating, especially for radical or creative thought. Enter the situation, where you construct authentic, creative ways to liberate yourself from the Spectacle. This is where you are actually creating, making, doing something beyond the relationship of yourself to things you buy: this interactions with people beyond the mediation of established systems and commodity fetishism.

Ok, ok, enough of the details of Debord! I’ll get to my point on education. Let’s take a simplistic view and talk about the presentation of second-hand experiences with little participation and official sanction. I don’t know about you but that sounds a lot like the traditional lecturing style to me – high power-distance and low participation. Hierarchical enforcement and the weight of history, combined with a strong bureaucracy. Yup. That sounds like the Spectacle.

When we talk about engagement we often don’t go to the opposite end and discuss the problem of alienation. Educational culture can be frightening and alienating for people who aren’t used to it but, even when you are within it, aspects will continue to leap out and pit the individual (student or teacher) against the needs of the system itself (we must do this because that’s how it works).

So what can we do? Well, the Situationists valued play, freedom and critical thinking. They had a political agenda that I won’t address here (you can read about it in many places) – I’m going to look at ways to reduce alienation, increase creativity and increase exploration. In fact, we’ve already done this when we talk about active learning, collaborative learning and getting students to value each other as sources of knowledge as well as their teachers.

But we can go further. While many people wonder how students can invest vast amounts of energy into some projects and not others, bringing the ability to play into the equation makes a significant difference and it goes hand-in-hand with freedom. But this means giving students the time, the space, the skills and the associated activities that will encourage this kind of exploration. (We’ve been doing this in my school with open-ended, self-selected creative assignments where we can. Still working on how we can scale it) But the principle of exploration is one that we can explore across curricula, schools, and all aspects of society.

It’s interesting. So many people seem to complain about student limitations when they encounter new situations (there’s that word again) yet place students into a passive Spectacle where the experience is often worse than second-hand. When I read a text book, I am reading the words of someone who has the knowledge rather than necessarily creating it for myself. If I have someone reading those words to me from the front of a lecture theatre then I’m not only rigidly locked into a conforming position, bound to listen, but I’m having something that’s closer to a third-hand experience.

When you’re really into something, you climb all over it and explore it. Your passion drives your interest and it is your ability to play with the elements, turn them around, mash them up and actually create something is a very good indicator of how well you are working with that knowledge. Getting students to rewrite the classic “Hello World” program is a waste of time. Getting students to work out how to take the picture of their choice and create something new is valuable. The Spectacle is not what we want in higher education or education at all because it is limiting, dull, and, above all, boring.

To paraphrase Debord: “Boredom is always counter-educational. Always.”