The Kids are Alright (within statistical error)

Posted: April 21, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: blogging, community, data visualisation, design, education, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, reflection, thinking, tools 3 CommentsYou may have seen this quote, often (apparently inaccurately) attributed to Socrates:

“The children now love luxury; they have bad manners, contempt for authority; they show disrespect for elders and love chatter in place of exercise. Children are now tyrants, not the servants of their households. They no longer rise when elders enter the room. They contradict their parents, chatter before company, gobble up dainties at the table, cross their legs, and tyrannize their teachers.” (roughly 400BC)

Apparently this is either a paraphrase of Aristophanes or misquoted Plato – like all things attributed to Socrates, we have to remember that we don’t have his signature to any of them. However, it doesn’t really matter if Socrates said it because not only did Hesiod say something in 700BC:

“I see no hope for the future of our people if they are dependent on frivolous youth of today, for certainly all youth are reckless beyond words… When I was young, we were taught to be discreet and respectful of elders, but the present youth are exceedingly wise [disrespectful] and impatient of restraint”

And then we have Peter the Hermit in 1274AD:

“The world is passing through troublous times. The young people of today think of nothing but themselves. They have no reverence for parents or old age. They are impatient of all restraint. They talk as if they knew everything, and what passes for wisdom with us is foolishness with them. As for the girls, they are forward, immodest and unladylike in speech, behavior and dress.”

(References via the Wikiquote page of Socrates and a linked discussion page.)

Let me summarise all of this for you:

You dang kids! Get off my lawn.

As you know, I’m a facty-analysis kind of guy so I thought that, if these wise people were correct and every generation is steadily heading towards mental incapacity and moral turpitude, we should be able to model this. (As an aside, I love the word turpitude, it sounds like the state of mind a turtle reaches after drinking mineral spirits.)

So let’s do this, let’s assume that all of these people are right and that the youth are reckless, disrespectful and that this keeps happening. How do we model this?

It’s pretty obvious that the speakers in question are happy to set themselves up as people who are right, so let’s assume that a human being’s moral worth starts at 100% and that all of these people are lucky enough to hold this state. Now, since Hesiod is chronologically the first speaker, let’s assume that he is lucky enough to be actually at 100%. Now, if the kids aren’t alright, then every child born will move us away from this state. If some kids are ok, then they won’t change things. Of course, every so often we must get a good one (or Socrates’ mouthpiece and Peter the Hermit must be aliens) so there should be a case for positive improvement. But we can’t have a human who is better than 100%, work with me here, and we shall assume that at 0% we have the worst person you can think of.

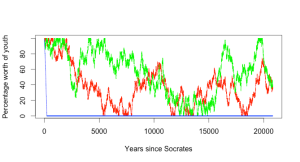

What we are now modelling is a random walk, starting at 100 and then adding some combination of -1, 0 or 1 at some regular interval. Let me cut to the chase and show you what this looks like, when modelled. I’ve assumed, for ease of modelling, that we make the assessment of the children every year and we have at most a 1 percentile point shift in that year, whatever other assumptions I made. I’ve provided three different models, one where the kids are terrible – we choose very year from no change or a negative shift. The next model is that the kids have some hope but sometimes do nothing, and we choose from an improvement, no change or steady moral decline! The final model is one where we either go up or down. Let’s look at a random walk across all three models over the span of years from 700BC to today:

As you can see, if we take the dire predictions of the next generation as true, then it is only a few hundred years before everything collapses. However, as expected, random walks over this range move around and hit a range of values. (Right now, you should look up Gambler’s Ruin to see why random walks are interesting – basically, over an infinite time, you’d expect to hit all of the values in the range from 0 to 100 an infinite number of times. This is why gamblers with small pots of money struggle against casinos with effectively infinite resources. Maths.)

But we know that the ‘everything is terrible’ model doesn’t work because both Socrates and Peter the Hermit consider themselves to be moral and both lived after the likely ‘decline to zero’ point shown in the blue line. But what would happen over longer timeframes? Let’s look at 20,000 and 200,000 years respectively. (These are separately executed random walks so the patterns will be different in each graph.)

What should be apparent, even with this rather pedantic exploration of what was never supposed to be modelled is that, even if we give credence to these particular commentators and we accept that there is some actual change that is measurable and shows an improvement or decline between generations, the negative model doesn’t work. The longer we run this, the more it will look like the noise that it is – and that is assuming that these people were right in the first place.

Personally, I think that the kids of this generation are pretty much the same as the one before, with some different adaptation to technology and societal mores. Would I have wasted time in lectures Facebooking if I had the chance? Well, I wasted it doing everything else so, yes, probably. (Look around your next staff meeting to see how many people are checking their mail. This is a technological shift driven by capability, not a sign of accelerating attention deficit.) Would I have spent tons of times playing games? Would I? I did! They were just board, role-playing and simpler computer games. The kids are alright and you can see that from the graphs – within statistical error.

Every time someone tells me that things are different, but it’s because the students are not of the same calibre as the ones before… well, I look at these quotes over the past 2,500 and I wonder.

And I try to stay off their lawn.

The Limits of Expressiveness: If Compilers Are Smart, Why Are We Doing the Work?

Posted: January 23, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: 'pataphysics, collaboration, community, curriculum, data visualisation, design, education, educational problem, higher education, principles of design, programming, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools 2 CommentsI am currently on holiday, which is “Nick shorthand” for catching up on my reading, painting and cat time. Recently, my interests in my own discipline have widened and I am precariously close to that terrible state that academics sometimes reach when they suddenly start uttering words like “interdisciplinary” or “big tent approach”. Quite often, around this time, the professoriate will look at each other, nod, and send for the nice people with the butterfly nets. Before they arrive and cart me away, I thought I’d share some of the reading and thinking I’ve been doing lately.

My reading is a little eclectic, right now. Next to Hooky’s account of the band “Joy Division” sits Dennis Wheatley’s “They Used Dark Forces” and next to that are four other books, which are a little more academic. “Reading Machines: Towards an Algorithmic Criticism” by Stephen Ramsay; “Debates in the Digital Humanities” edited by Matthew Gold; “10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); : GOTO 10” by Montfort et al; and “‘Pataphysics: A Useless Guide” by Andrew Hugill. All of these are fascinating books and, right now, I am thinking through all of these in order to place a new glass over some of my assumptions from within my own discipline.

“10 PRINT CHR$…” is an account of a simple line of code from the Commodore 64 Basic language, which draws diagonal mazes on the screen. In exploring this, the authors explore fundamental aspects of computing and, in particular, creative computing and how programs exist in culture. Everything in the line says something about programming back when the C-64 was popular, from the use of line numbers (required because you had to establish an execution order without necessarily being able to arrange elements in one document) to the use of the $ after CHR, which tells both the programmer and the machine that what results from this operation is a string, rather than a number. In many ways, this is a book about my own journey through Computer Science, growing up with BASIC programming and accepting its conventions as the norm, only to have new and strange conventions pop out at me once I started using other programming languages.

Rather than discuss the other books in detail, although I recommend all of them, I wanted to talk about specific aspects of expressiveness and comprehension, as if there is one thing I am thinking after all of this reading, it is “why aren’t we doing this better”? The line “10 PRINT CHR$…” is effectively incomprehensible to the casual reader, yet if I wrote something like this:

do this forever

pick one of “/” or “\” and display it on the screen

then anyone who spoke English (which used to be a larger number than those who could read programming languages but, honestly, today I’m not sure about that) could understand what was going to happen but, not only could they understand, they could create something themselves without having to work out how to make it happen. You can see language like this in languages such as Scratch, which is intended to teach programming by providing an easier bridge between standard language and programming using pre-constructed blocks and far more approachable terms. Why is it so important to create? One of the debates raging in Digital Humanities at the moment, at least according to my reading, is “who is in” and “who is out” – what does it take to make one a digital humanist? While this used to involve “being a programmer”, it is now considered reasonable to “create something”. For anyone who is notionally a programmer, the two are indivisible. Programs are how we create things and programming languages are the form that we use to communicate with the machines, to solve the problems that we need solved.

When we first started writing programs, we instructed the machines in simple arithmetic sequences that matched the bit patterns required to ensure that certain memory locations were processed in a certain way. We then provided human-readable shorthand, assembly language, where mnemonics replaced numbers, to make it easier for humans to write code without error. “20” became “JSR” in 6502 assembly code, for example, yet “JSR” is as impenetrably occulted as “20” unless you learn a language that is not actually a language but a compressed form of acronym. Roll on some more years and we have added pseudo-English over the top: GOSUB in Basic and the use of parentheses to indicate function calls in other languages.

However, all I actually wanted to do was to make the same thing happen again, maybe with some minor changes to what it was working on. Think of a sub-routine (method, procedure or function, if we’re being relaxed in our terminology) and you may as well think of a washing machine. It takes in something and combines it with a determined process, a machine setting, powders and liquids to give you the result you wanted, in this case taking in dirty clothes and giving back clean ones. The execution of a sub-routine is identical to this but can you see the predictable familiarity of the washing machine in JSR FE FF?

If you are familiar with ‘Pataphysics, or even “Ubu Roi” the most well-known of Jarry’s work, you may be aware of the pataphysician’s fascination with the spiral – le Grand Gidouille. The spiral, once drawn, defines not only itself but another spiral in the negative space that it contains. The spiral is also a natural way to think about programming because a very well-used programming language construct, the for loop, often either counts up to a value or counts down. It is not uncommon for this kind of counting loop to allow us to advance from one character to the next in a text of some sort. When we define a loop as a spiral, we clearly state what it is and what it is not – it is not retreading old ground, although it may always spiral out towards infinity.

However, for maximum confusion, the for loop may iterate a fixed number of times but never use the changing value that is driving it – it is no longer a spiral in terms of its effect on its contents. We can even write a for loop that goes around in a circle indefinitely, executing the code within it until it is interrupted. Yet, we use the same keyword for all of these.

In English, the word “get” is incredibly overused. There are very few situations when another verb couldn’t add more meaning, even in terms of shade, to the situation. Using “get” forces us, quite frequently, to do more hard work to achieve comprehension. Using the same words for many different types of loop pushes load back on to us.

What happens is that when we write our loop, we are required to do the thinking as to how we want this loop to work – although Scratch provides a forever, very few other languages provide anything like that. To loop endlessly in C, we would use while (true) or for (;;), but to tell the difference between a loop that is functioning as a spiral, and one that is merely counting, we have to read the body of the loop to see what is going on. If you aren’t a programmer, does for(;;) give you any inkling at all as to what is going on? Some might think “Aha, but programming is for programmers” and I would respond with “Aha, yes, but becoming a programmer requires a great deal of learning and why don’t we make it simpler?” To which the obvious riposte is “But we have special languages which will do all that!” and I then strike back with “Well, if that is such a good feature, why isn’t it in all languages, given how good modern language compilers are?” (A compiler is a program that turns programming languages into something that computers can execute – English words to byte patterns effectively.)

In thinking about language origins, and what we are capable of with modern compilers, we have to accept that a lot of the heavy lifting in programming is already being done by modern, optimising, compilers. Years ago, the compiler would just turn your instructions into a form that machines could execute – with no improvement. These days, put something daft in (like a loop that does nothing for a million iterations), and the compiler will quietly edit it out. The compiler will worry about optimising your storage of information and, sometimes, even help you to reduce wasted use of memory (no, Java, I’m most definitely not looking at you.)

So why is it that C++ doesn’t have a forever, a do 10 times, or a spiral to 10 equivalent in there? The answer is complex but is, most likely, a combination of standards issues (changing a language standard is relatively difficult and requires a lot of effort), the fact that other languages do already do things like this, the burden of increasing compiler complexity to handle synonyms like this (although this need not be too arduous) and, most likely, the fact that I doubt that many people would see a need for it.

In reading all of these books, and I’ll write more on this shortly, I am becoming increasingly aware that I tolerate a great deal of limitation in my ability to solve problems using programming languages. I put up with having my expressiveness reduced, with taking care of some unnecessary heavy lifting in making things clear to the compiler, and I occasionally even allow the programming language to dictate how I write the words on the page itself – not just syntax and semantics (which are at least understandably, socially and technically) but the use of blank lines, white space and end of lines.

How are we expected to be truly creative if conformity and constraint are the underpinnings of programming? Tomorrow, I shall write on the use of constraint as a means of encouraging creativity and why I feel that what we see in programming is actually limitation, rather than a useful constraint.

Brief Stats Update: Penultimate Word Count Notes

Posted: December 8, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, data visualisation, design, education, educational problem, educational research, higher education, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, work/life balance, workload, writing Leave a commentI occasionally dump the blog and run it through some Python script deliciousness to find out how many words I’ve written. This is no measure of worth or quality, more a metric of my mania. As I noted in October, I was going to hit what I thought was my year target much earlier. Well, yes, it came and it went and, sure enough, I plowed through it. At time of writing, on published posts alone, we’re holding at around 1.2 posts/day, 834 words/post and a smidgen over 340,000 words, which puts me (in word count) just after Ayn Rand’s “The Fountainhead” (311,596) but well behind her opus “Atlas Shrugged” (561,996). In terms of Objectivism? Let’s just say that I won’t be putting any kind of animal into that particular fight at the moment.

Now, of course, I can plug in the numbers and see that this puts my final 2012 word count somewhere in the region of 362,000 words. I must admit, there is a part of me that sees that number and thinks “Well, we could make it an even 365,000 and that’s a neat 1000 words/day” but, of course, that’s dumb for several reasons:

- I have not checked in detail exactly how well my extraction software is grabbing the right bits of the text. There are hyperlinks and embellishments that appear to be taken care of, but we are probably only on the order of 95% accuracy here. Yes, I’ve inspected it and I haven’t noticed anything too bad, but there could be things slipping through. After all of this is over, I am going to drag it all together and analyse it properly but, let me be clear, just because I can give you a word count to 6 significant figures, doesn’t mean that it is accurate to 6 significant figures.

- Should I even be counting those sections of text that are quoted? I do like to put quotes in, sometimes from my own work, and this now means I’m either counting something that I didn’t write or I’m counting something that I did write twice!

- Should I be counting the stats posts themselves as they are, effectively, metacontent? This line item is almost above that again! This way madness lies!

- It was never about the numbers in the first place, it was about thinking about my job, my students, my community and learning and teaching. That goal will have been achieved whether I write one word/day from now on or ten thousand!

But, oh, the temptation to aim for that ridiculous and ultimately deceptive number. How silly but, of course, how human to look at the measurable goal rather than the inner achievement or intrinsic reward that I have gained from the thinking process, the writing, the refining of the text, the assembly of knowledge and the discussion.

Sometime after January the 1st, I will go back and set the record straight. I shall dump the blog and analyse it from here to breakfast time. I will release the data to interested (and apparently slightly odd) people if they wish. But, for now, this is not the meter that I should be watching because it is not measuring the progress that I am making, nor is it a good compass that I should follow.

I Can’t Find My Paperless Office For All The Books

Posted: December 8, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, blogging, book, data visualisation, design, education, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, literature, measurement, principles of design, resources, student perspective, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, writing 2 CommentsI tidied up my office recently and managed to clear out about a couple of boxes full of old paper. Some of these were working drafts of research papers, covered in scrawl (usually red because it shows up more), some were book chapter mark-ups, and some were things like project meeting plans that I could scribble on as people spoke. All of this went into either the secure waste bins (sekrit stuff) or the general recycling because I do try to keep the paper footprint down. However, my question to myself is two-fold:

- Why do I still have an office full of paper when I have a desktop, (two) laptops, an iPad and an iPhone, and I happily take notes and annotate documents on them?

- Why am I surrounded by so many books, still?

I don’t think I’ve ever bought as many books as I have bought this year. By default, if I can, I buy them as the electronic and paper form so that I can read them when I travel or when I’m in the office. There are books on graphic design, books on semiotics, books on data visualisation and analysis, and now, somewhat recursively, books on the end of books. My wife found me a book called “This is not the end of the book”, which is a printed conversation between Umberto Eco and Jean-Claude Carrière, curated by Jean-Philippe de Tonnac. I am looking forward to reading it but it has to wait until some of the other books are done. I have just finished Iain M. Banks latest “The Hydrogen Sonata”, am swimming through an unauthorised biography of Led Zeppelin and am still trying to finish off the Derren Brown book that I have been reading on aeroplanes for the past month or so. Sitting behind all this are “Cloud Atlas” and “1Q84”, both of which are officially waiting until I have finished my PhD application portfolio for creative writing. (Yes, dear reader, I’m nervous because they could as easily say ‘No’ as ‘Yes’ but then I will learn how to improve and, if I can’t take that, I shouldn’t be teaching. To thine own dogfood, be as a consumer.)

Why do I still write on paper? Because it feels good. I select pens that feel good to write with, or pencils soft enough to give me a good relationship to the paper. The colour of ink changes as it hits the paper and dries and I am slightly notorious for using inks that do not dry immediately. When I was a winemaker, I used black Bic fine pens, when many other people used wet ink or even fountain pens, because the pen could write on damp paper and, even when you saturated the note, the ink didn’t run. These days, I work in an office and I have the luxury of using a fountain pen to scrawl in red or blue across documents, and I can enjoy the sensation.

Why do I still read on paper? Because it is enjoyable and I have a long relationship with the book, which began from a very early age. The book is also, nontrivially, one of the few information storage devices that can be carried on to a plane without having to be taken from one’s bag or shut down for the periods of take off and landing. I am well aware of the most dangerous points in an aircraft’s cycle and I strongly prefer to be distracted by, if not in-flight entertainment, then a good solid book. But it is also the pleasure of being able to separate the book from the devices that link me into my working world, yet without adding a new data storage management issue. Yes, I could buy a Kindle and not have to check my e-mail, but then I have to buy books from this store and I have to carry that charger or fit it next to my iPad, laptop and phone when travelling. Books, once read, can either be donated to your hosts in another place or can be tossed into the suitcase, making room for yet more books – but of course a device may carry many books. If I have no room in my bag for a book, then I don’t have to worry about the fragility of making space in my carry-on by putting it into the suitcase.

And, where necessary, the book/spider interaction causes more damage to the spider than the contents of the book. My thesis was sufficiently large to stun a small mammal, but you would not believe how hard it was to get ethical approval for that!

The short answer to both questions is that I enjoy using the physical forms although I delight in the practicality, the convenience and the principle of the electronic forms. I am a happy hybridiser who wishes only to enjoy the experience of reading and writing in a way that appeals to me. In a way, the electronic format makes it easier for me to share my physical books. I have a large library of books from when I was younger that, to my knowledge, has books that it is almost impossible to find in print or libraries any more. Yet, I am in that uncomfortable position of being a selfish steward, in that I cannot release some of these books for people to read because I hold the only copy that I know of. As I discover more books in electronic or re-print format (the works of E. Nesbit, Susan Cooper in the children’s collection of my library, for example) then I am free to use the books as they were intended, as books.

What we have now, what is emerging, certainly need not be the end of the book but it will be interesting to look back, in fifty years or so, to find out what we did. If the book has become the analogue watch of information, where it moved from status symbol for its worth, to status symbol for its value, to affectation and, now, to many of my students, an anachronism for those who don’t have good time signal on their phones. I suspect that a watch does not have the sheer enjoyability of the book or the pen on paper, but, if you will excuse me, time will tell.

Data Visualisation: Strong Messages Educate Better

Posted: December 7, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, data visualisation, design, education, higher education, principles of design, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools 1 CommentKnow what this is?

Rather pretty, isn’t it – but it has a definite direction, like someone has throw something from the right and it has hit the ground and scattered.

This image is from the Bomb Sight website, and shows all of the bombs that fell on London (and surrounds) from the 7th of October, 1940, to the 6th of June, 1941. The Bomb Sight team have been working from a variety of data sources to put together a reasonably reliable picture of the recorded bombs on London over that 242 day period. If you zoom in (and it starts zoomed in), you start to see how many sites took 2, 3, 4 or more bombs (10, 11, plus) over that time.

If I were to put together a number of bombs and a number of days and say “X bombs fell in London over Y days”, you could divide X by Y and say “Gosh.” Or I can show you a picture like the one above and tell you that each of those dots represents at least one bomb, possibly as many as 10 or so, and watch your jaw drop.

Seen this way, the Blitz becomes closer to those of us who were fortunate enough not to live through that terrible period. We realise any number of things, most of which is that close proximity to a force who wishes you ill is going to result in destruction and devastation of a level that we might not be able to get our heads around, unless we see it.

Seen this way, it’s a very strong message of what actually happened. It has more power. In a world of big numbers and enormous data, it’s important to remember how we can show things so that we tell their stories in the right way. Numbers can be ignored. Pictures tell better stories, as long as we are honest and truthful in the way that we use them.

Game Design and Boredom: Learning From What I Like

Posted: November 25, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, data visualisation, design, education, games, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, zombies 5 CommentsFor those of you poor deluded souls who are long term readers (or long term “receivers of e-mail that you file under the ‘read while anaesthetised’ folder”) you will remember that I talked about producing a zombie game some time ago and was crawling around the house to work out how fast you could travel as a legless zombie. Some of you (well, one of you – thanks, Mark) has even sent me appropriately English pictures to put into my London-based game. Yet, as you can see, there is not yet a game.

What happened?

The first thing I wanted to do was to go through the design process and work out if I could produce a playable game that worked well. Along the way, however, I’ve discovered a lot of about games because I have been thinking in far more detail about games and about why I like to play the games that I enjoy. To quote my previous post:

I play a number of board games but, before you think “Oh no, not Monopoly!”, these are along the lines of the German-style board games, games that place some emphasis on strategy, don’t depend too heavily on luck, may have collaborative elements (or an entirely collaborative theme), tend not to be straight war games and manage to keep all the players in the game until the end.

What I failed to mention, you might notice, is that I expect these games to be fun. As it turns out, the first design for the game actually managed to meet all of the above requirements and, yet, was not fun in any way at all. I realised that I had fallen into a trap that I am often prone to, which is that I was trying to impose a narrative over a set of events that could actually occur in any order or any way.

Ever prepared for a class, with lots of materials for one specific area, and then the class takes a sudden shift in direction (it turns out that the class haven’t assimilated a certain foundation concept) and all of that careful work has to be put away for later? Sometimes it doesn’t matter how much you prepare – life happens and your carefully planned activities get derailed. Even if you don’t get any content surprises, it doesn’t take much to upset the applecart (a fire alarm goes off, for example) and one of the signs of the good educator is the ability to adapt to continue to bring the important points to the learner, no matter what happens. Walking in with a fixed narrative of how the semester is going to roll out is unlikely to meet the requirements of all of your students and if something goes wrong, you’re stuffed (to use the delightful Australian vernacular, which seems oddly appropriate around Thanksgiving).

In my head, while putting my game together, I had thought of a set of exciting stories, rather than a possible set of goals, events and rules that could apply to any combination of players and situations. When people have the opportunity to explore, they become more engaged and they tend to own the experience more. This is what I loved about the game Deus Ex, the illusion of free will, and I felt that I constructed my own narrative in there, despite actually choosing from one of the three that was on offer on carefully hidden rails that you didn’t see until you’d played it through a few times.

Apart from anything else, I had made the game design dull. There is nothing exciting about laying out hexagonal tiles to some algorithm, unless you are getting to pick the strategy, so my ‘random starting map’ was one of the first things to go. London has a number of areas and, by choosing a fixed board layout that increased or decreased based on player numbers, I got enough variation by randomising placement on a fixed map.

I love the game Arkham Horror but I don’t play it very often, despite owning all of the expansions. Why? The set-up and pack-up time take ages. Deck after deck of cards, some hundreds high, some 2-3, have to be placed out onto a steadily shrinking playing area and, on occasion, a player getting a certain reward will stop the game for 5-10 minutes as we desperately search for the appropriate sub-pack and specific card that they have earned. The game company that released Arkham has now released iPhone apps that allow you to monitor cards on your phone but, given that each expansion management app is an additional fee and that I have already paid money for the expansions themselves, this has actually added an additional layer of irritation. The game company recognises that their system is painful but now wish to charge me more money to reduce the problem! I realised that my ‘lay out the hexes’ for the game was boring set-up and a barrier to fun.

The other thing I had to realise is that nobody really cares about realism or, at least, there is only so much realism people need. I had originally allows for players to be soldiers, scientists, police, medical people, spies and administrators. Who really wants to be the player responsible for the budgetary allocation of a large covert government facility? Just because the administrator has narrative value doesn’t mean that the character will be fun to play! Similarly, why the separation between scientists and doctors? All that means is I have the unpleasant situation where the doctors can’t research the cure and the scientists can’t go into the field because they have no bandaging skill. If I’m writing a scenario as a novel or short story, I can control the level of engagement for each character because I’m writing the script. In a randomised series of events, no-one is quite sure who will be needed where and the cardinal rule of a game is that it should be fun. In fact, that final goal of keeping all players in the game until the end should be an explicit statement that all players are useful in the game until the end.

The games I like are varied but the games that I play have several characteristics in common. They do not take a long time to set-up or pack away. They allow every player to matter, up until the end. Whether working together or working against each other, everyone feels useful. There is now so much randomness that you can be destroyed by a bad roll but there is not so much predictability that you can coast after the second round. The games I really like to play are also forgiving. I am playing some strategy games at the moment and, for at least two of them, decisions made in the first two rounds will affect the entire game. I must say that I’m playing them to see if that is my lack of ability or a facet of the game. If it turns out to be the game, I’ll stop playing because I don’t need to have a game berating me for making a mistake 10 rounds previously. It’s not what I call fun.

I hope to have some more time to work on this over the summer but, as a design exercise, it has been really rewarding for me to think about. I understand myself more and I understand games more – and this means that I am enjoying the games that I do play more as well!

Ebb and Flow – Monitoring Systems Without Intrusion

Posted: November 23, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: collaboration, community, curriculum, data visualisation, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, MIKE, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, SWEDE, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools Leave a commentI’ve been wishing a lot of people “Happy Thanksgiving” today because, despite being frightfully Antipodean, I have a lot of friends and family who are Thanksgiving observers in the US. However, I would know that something was up in the US anyway because I am missing about 40% of my standard viewers on my blog. Today is an honorary Sunday – hooray, sleep-ins all round! More seriously, this illustrates one of the most interesting things about measurement, which is measuring long enough to be able to determine when something out of the ordinary occurs. As I’ve already discussed, I can tell when I’ve been linked to a higher profile blog because my read count surges. I also can tell when I haven’t been using attractive pictures because the count drops by about 30%.

A fruit bat, in recovery, about to drink its special fruit smoothie. (Yes, this is shameless manipulation.)

This is because I know what the day-to-day operation of the blog looks like and I can spot anomalies. When I was a network admin, I could often tell when something was going wrong on the network just because of the way that certain network operations started to feel, and often well before these problems reached the level where they would trigger any sort of alarm. It’s the same for people who’ve lived by the same patch of sea for thirty years. They’ll look at what appears to be a flat sea on a calm day and tell you not to go out – because they can read a number of things from the system and those things mean ‘danger’.

One of the reasons that the network example is useful is because any time you send data through the network to see what happens, you’re actually using the network to do it. So network probes will actually consume network bandwidth and this may either mask or exacerbate your problems, depending on how unlucky you are. However, using the network for day-today operations, and sensing that something is off, then gives you a reason to run those probes or to check the counters on your networking gear to find out exactly why the hair on the back of your neck is going up.

I observe the behaviour of my students a lot and I try to gain as much information as I can from what they already give me. That’s one of the reasons that I’m so interested in assignment submissions, because students are going to submit assignments anyway and any extra information I can get from this is a giant bonus! I am running a follow-up Piazza activity on our remote campus and I’m fascinated to be able to watch the developing activity because it tells me who is participating and how they are participating. For those who haven’t heard about Piazza, it’s like a Wiki but instead of the Wiki model of “edit first, then argue into shape”, Piazza encourages a “discuss first and write after consensus” model. I put up the Piazza assignment for the class, with a mid-December deadline, and I’ve already had tens of registered discussions, some of which are leading to edits. Of course, not all groups are active yet and, come Monday, I’ll send out a reminder e-mail and chat to them privately. Instead of sending a blanket mail to everyone saying “HAVE YOU STARTED PIAZZA”, I can refine my contact based on passive observation.

The other thing about Piazza is that, once all of the assignment is over, I can still see all of their discussions, because that’s where I’ve told them to have the discussion! As a result, we can code their answers and track the development of their answers, classifying them in terms of their group role, their level of function and so on. For an open-ended team-based problem, this allows me a great deal of insight into how much understanding my students have of the area and allows me to fine-tune my teaching. Being me, I’m really looking for ways to improve self-regulation mechanisms, as well as uncovering any new threshold concepts, but this nonintrusive monitoring has more advantages than this. I can measure participation by briefly looking at my mailbox to see how many mail messages are foldered under a particular group’s ID, from anywhere, or I can go to Piazza and see it unfolding there. I can step in where I have to, but only when I have to, to get things back on track but I don’t have to prove or deconstruct a team-formed artefact to see what is going on.

In terms of ebb and flow, the Piazza groups are still unpredictable because I don’t have enough data to be able to tell you what the working pattern is for a successful group. I can tell you that no activity is undesirable but, even early on, I could tell you some interesting things about the people who post the most! (There are some upcoming publications that will deal with things along these lines and I will post more on these later.) We’ve been lucky enough to secure some Summer students and I’m hoping that at least some of their work will involve looking at dependencies in communication and ebb and flow across these systems.

As you may have guessed, I like simple. I like the idea of a single dashboard that has a green light (healthy course), an orange light (sick course) and a red light (time to go back to playing guitar on the street corner) although I know it will never be that easy. However, anything that brings me closer to that is doing me a huge favour, because the less time I have to spend actively probing in the course, the less of my students’ time I take up with probes and the less of my own time I spend not knowing what is going on!

Oh well, the good news is that I think that there are only three more papers to write before the Mayan Apocalypse occurs and at least one of them will be on this. I’ll see if I can sneak in a picture of a fruit bat. 🙂

The Hips Don’t Lie – Assuming That By Hips You Mean Numbers

Posted: November 12, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, blogging, community, data visualisation, education, ethics, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, measurement, MIKE, nate silver, principles of design, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design Leave a commentFor those who missed it, the United States went to the polls to elect a new President. Some people were surprised by the outcome.

Some people were not, including the new King of Quants, Nate Silver. Silver studied economics at the University of Chicago but really came to prominence in his predictions of baseball outcomes, based on his analysis of the associated statistics and sabermetrics. He correctly predicted, back in 2008, what would happen between Obama and Clinton, and he predicted, to the state, what the outcome would be in this year’s election, even in the notoriously fickle swing states. Silver’s approach isn’t secret. He looks at all of the polls and then generates a weighted average of them (very, very simplified) in order to value certain polls over others. You rerun some of the models, change some parameters, look at it all again and work out what the most likely scenario is. Nate’s been publishing this regularly on his FiveThirtyEight blog (that’s the number of electors in the electoral college, by the way, and I had to look that up because I am not an American) which is now a feature of the New York Times.

So, throughout the entire election, as journalists and the official voices have been ranting and railing, predicting victory for this candidate or that candidate, Nate’s been looking at the polls, adjusting his model and publishing his predictions. Understandably, when someone is predicting a Democratic victory, the opposing party is going to jump up and down a bit and accusing Nate of some pretty serious bias and poll fixing. However, unless young Mr Silver has powers beyond those of mortal men, fixing all 538 electors in order to ensure an exact match to his predictions does seem to be taking fixing to a new level – and, of course, we’re joking because Nate Silver was right. Why was he right? Because he worked out a correct mathematical model and method that took into account how accurate each poll was likely to be in predicting the final voter behaviour and that reliable, scientific and analytic approach allowed him to make a pretty conclusive set of predictions.

There are notorious examples of what happens when you listen to the wrong set of polls, or poll in the wrong areas, or carry out a phone poll at a time when (a) only rich people have phones or (b) only older people have landlines. Any information you get from such biased polls has to be taken with a grain of salt and weighted to reduce a skewing impact, but you have to be smart in how you weight things. Plain averaging most definitely does not work because this assumes equal sized populations or that (mysteriously) each poll should be treated as having equal weight. Here’s the other thing, though, ignoring the numbers is not going to help you if those same numbers are going to count against you.

Example: You’re a student and you do a mock exam. You get 30% because you didn’t study. You assume that the main exam will be really different. You go along. It’s not. In fact, it’s the same exam. You get 35%. You ignored the feedback that you should have used to predict what your final numbers were going to be. The big difference here is that a student can change their destiny through their own efforts. Changing the mind of the American people from June to November (Nate published his first predictions in June) is going to be nearly impossible so you’re left with one option, apparently, and that’s to pretend that it’s not happening.

I can pretend that my car isn’t running out of gas but, if the gauge is even vaguely accurate, somewhere along the way the car is going to stop. Ignoring Nate’s indications of what the final result would be was only ever going to work if his model was absolutely terrible but, of course, it was based on the polling data and the people being polled were voters. Assuming that there was any accuracy to the polls, then it’s the combination of the polls that was very clever and that’s all down to careful thought and good modelling. There is no doubt that a vast amount of work has gone into producing such a good model because you have to carefully work out how much each vote is worth in which context. Someone in a blue-skewed poll votes blue? Not as important as an increasing number of blue voters in a red-skewed polling area. One hundred people polled in a group to be weighted differently from three thousand people in another – and the absence of certain outliers possibly just down to having too small a sample population. Then, just to make it more difficult, you have to work out how these voting patterns are going to turn into electoral college votes. Now you have one vote that doesn’t mean the difference between having Idaho and not having Idaho, you have a vote that means the difference between “Hail to the Chief” and “Former Presidential Candidate and Your Host Tonight”.

Nate Silver’s work has brought a very important issue to light. The numbers, when you are thorough, don’t lie. He didn’t create the President’s re-election, he merely told everyone that, according to the American people, this was what was going to happen. What is astounding to me, and really shouldn’t be, is how many commentators and politicians seemed to take Silver’s predictions personally, as if he was trying to change reality by lying about the numbers. Well, someone was trying to change public perception of reality by talking about numbers, but I don’t think it was Nate Silver.

This is, fundamentally, a victory for science, thinking and solid statistics. Nate put up his predictions in a public space and said “Well, let’s see” and, with a small margin for error in terms of the final percentages, he got it right. That’s how science is supposed to work. Look at stuff, work out what’s going on, make predictions, see if you’re right, modify model as required and repeat until you have worked out how it really works. There is no shortage of Monday morning quarterbacks who can tell you in great detail why something happened a certain way when the game is over. Thanks, Nate, for giving me something to show my students to say “This is what it looks like when you get data science right.”

Remind me, however, never to bet against you at a sporting event!

369 (+2)

Posted: November 3, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, data visualisation, design, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches 1 CommentThe post before my previous post was my 369th post. I only saw because I’m in manual posting mode at the moment and it’s funny how my brain immediately started to pull the number apart. It’s the first three powers of 3, of course, 3, 6, 9, but it’s also 123 x 3 (and I almost always notice 1,2,3). It’s divisible by 9 (because the digits add up to 9), which means it’s also divisible by 3 (which give us 123 as I said earlier). So it’s non-prime (no surprises there). Some people will trigger on the 36x part because of the 365/366 number of days in the year.

That’s pretty much where I stop on this, and no doubt there will be much more in the comments from more mathematical folk than I, but numbers almost always pop out at me. Like some people (certainly not all) in the fields of Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics, numbers and facts fascinate me. However, I know many fine Computer Scientists who do not notice these things at all – and this is one of those great examples where the stereotypes fall down. Our discipline, like all the others, has mathematical people, some of whom are also artists, musicians, poets, jugglers, juggalos, but it also has people who are not as mathematical. This is one of the problems when we try to establish who might be good at what we do or who might enjoy it. We try to come up with a simple identification scheme that we can apply – the risk being, of course, that if we get it wrong we risk excluding more people than we include.

So many students tell me that they can’t do computing/programming because they’re no good at maths. Point 1, you’re probably better at maths than you think, but Point 2, you don’t have to be good at maths to program unless you’re doing some serious formal and proof work, algorithmic efficiencies or mathematical scientific programming. You can get by on a reasonable understanding of the basics, and yes, I do mean algebra here but very, very low level, and focus as you need to. Yes, certain things will make more sense if your mind is trained in a certain way, but this comes with training and practice.

It’s too easy to put people in a box when they like or remember numbers, and forget that half the population (at one stage) could bellow out 8675309 if they were singing along to the radio. Or recite their own phone number from the house they lived in when they were 10, for that matter. We’re all good for about 7 digit numbers, and a few of these slots, although the introduction of smart phones has reduced the number of numbers we have to remember.

So in this 369(+2)th post, let me speak to everyone out there who ever thought that the door to programming was closed because they couldn’t get through math, or really didn’t enjoy it. Programming is all about solving problems, only some of which are mathematical. Do you like solving problems? Did you successfully dress yourself today?

Did you, at any stage in the past month, run across an unfamiliar door handle and find yourself able to open it, based on applying previous principles, to the extent that you successfully traversed the door? Congratulations, human, you have the requisite skills to solve problems. Programming can give you a set of tools to apply that skill to bigger problems, for your own enjoyment or to the benefit of more people.

Road to Intensive Teaching: Post 1

Posted: November 2, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, collaboration, community, curriculum, data visualisation, design, education, educational problem, educational research, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, networking, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools Leave a commentI’m back on the road for intensive teaching mode again and, as always, the challenge lies in delivering 16 hours of content in a way that will stick and that will allow the students to develop and apply their understanding of the core knowledge. Make no mistake, these are keen students who have committed to being here, but it’s both warm and humid where I am and, after a long weekend of working, we’re all going to be a bit punch-drunk by Sunday.

That’s why there is going to be a heap of collaborative working, questioning, voting, discussion. That’s why there are going to be collaborative discussions of connecting machines and security. Computer Networking is a strange beast at the best of times because it’s often presented as a set of competing models and protocols, with very few actual axioms beyond “never early adopt anything because of a vendor promise” and “the only way to merge two standards is by developing another standard. Now you have three standards.”

There is a lot of serious Computer Science lurking in networking. Algorithmic efficiency is regularly considered in things like routing convergence and the nature of distributed routing protocols. Proofs of correctness abound (or at least are known about) in a variety of protocols that , every day, keep the Internet humming despite all of the dumb things that humans do. It’s good that it keeps going because the Internet is important. You, as a connected being, are probably smarter than you, disconnected. A great reach for your connectivity is almost always a good thing. (Nyancat and hate groups notwithstanding. Libraries have always contained strange and unpleasant things.)

“If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants” (Newton, quoting Bernard of Chartres) – the Internet brings the giants to you at a speed and a range that dwarfs anything we have achieved previously in terms of knowledge sharing. It’s not just about the connections, of course, because we are also interested in how we connect, to whom we connect and who can read what we’re sharing.

There’s a vast amount of effort going into making the networks more secure and, before you think “Great, encrypted cat pictures”, let me reassure you that every single thing that comes out of your computer could, right now, be secretly and invisibly rerouted to a malicious third party and you would never, ever know unless you were keeping a really close eye (including historical records) on your connection latency. I have colleagues who are striving to make sure that we have security protocols that will make it harder for any country to accidentally divert all of the world’s traffic through itself. That will stop one typing error on a line somewhere from bringing down the US network.

“The network” is amazing. It’s empowering. It is changing the way that people think and live, mostly for the better in my opinion. It is harder to ignore the rest of the world or the people who are not like you, when you can see them, talk to them and hear their stories all day, every day. The Internet is a small but exploding universe of the products of people and, increasingly, the products of the products of people.

Computer Networking is really, really important for us in the 21st Century. Regrettably, the basics can be a bit dull, which is why I’m looking to restructure this course to look at interesting problems, which drives the need for comprehensive solutions. In the classroom, we talk about protocols and can experiment with them, but even when we have full labs to practise this, we don’t see the cosmos above, we see the reality below.

Nobody is interested in the compaction issues of mud until they need to build a bridge or a road. That’s actually very sensible because we can’t know everything – even Sherlock Holmes had his blind spots because he had to focus on what he considered to be important. If I give the students good reasons, a grand framing, a grand challenge if you will, then all of the clicking, prodding, thinking and protocol examination suddenly has a purpose. If I get it really right, then I’ll have difficulty getting them out of the classroom on Sunday afternoon.

Fingers crossed!

(Who am I kidding? My fingers have an in-built crossover!)