Let’s not turn “Chalk and Talk” into “Watch and Scratch”

Posted: July 1, 2013 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, higher education, moocs, principles of design, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, tools, universal principles of design 1 CommentWe are now starting to get some real data on what happens when people “take” a MOOC (via Mark’s blog). You’ll note the scare quotes around the word “take”, because I’m not sure that we have really managed to work out what it means to get involved in a course that is offered through the MOOC mechanism. Or, to be more precise, some people think they have but not everyone necessarily agrees with them. I’m going to list some of my major concerns, even in the face of the new clickstream data, and explain why we don’t have a clear view of the true value/approaches for MOOCs yet.

- On-line resources are not on-line courses and people aren’t clear on the importance of an overall educational design and facilitation mechanism. Many people have mused on this in the past. If all the average human needed was a set of resources and no framing or assistive pedagogy then our educational resources would be libraries and there would be no teachers. While there are a number of offerings that are actually courses, applying the results of the MIT 6.002x to what are, for the most part, unstructured on-line libraries of lecture recordings is not appropriate. (I’m not even going to get into the cMOOC/xMOOC distinction at this point.) I suspect that this is just part of the general undervaluing of good educational design that rears its head periodically.

- Replacing lectures with on-line lectures doesn’t magically improve things. The problem with “chalk and talk”, where it is purely one-way with no class interaction, is that we know that it is not an effective way to transfer knowledge. Reading the textbook at someone and forcing them to slowly transcribe it turns your classroom into an inefficient, flesh-based photocopier. Recording yourself standing in front a class doesn’t automatically change things. Yes, your students can time shift you, both to a more convenient time and at a more convenient speed, but what are you adding to the content? How are you involving the student? How can the student benefit from having you there? When we just record lectures and put them up there, then unless they are part of a greater learning design, the student is now sitting in an isolated space, away from other people, watching you talk, and potentially scratching their head while being unable to ask you or anyone else a question. Turning “chalk and talk” into “watch and scratch” is not an improvement. Yes, it scales so that millions of people can now scratch their heads in unison but scaling isn’t everything and, in particular, if we waste time on an activity under the illusion that it will improve things, we’ve gone backwards in terms of quality for effort.

- We have yet to establish the baselines for our measurement. This is really important. An on-line system us capable of being very heavily tracked and it’s not just links. The clickstream measurements in the original report record what people clicked on as they worked with the material. But we can only measure that which is set up for measurement – so it’s quite hard to compare the activity in this course to other activities that don’t use technology. But there are two subordinate problems to this (and I apologise to physicists for the looseness of the following) :

- Heisenberg’s MOOC: At the quantum scale, you can either tell where something is or what it is doing – the act of observation has limits of precision. Borrowing that for the macro scale: measure someone enough and you’ll see how they behave under measurement but the measurements we pick tend to fall into the stage they’ve reached or the actions they’ve taken. It’s very complex to combine quantitative and qualitative measures to be able to map someone’s stage and their comprehension/intentions/trajectory. You don’t have to accept arguments based on the Hawthorne Effect to understand why this does not necessarily tell you much about unobserved people. There are a large number of people taking these courses out of curiosity, some of whom already have appropriate qualifications, with only 27% the type of student that you would expect to see at this level of University. Combine that with a large number of researchers and curious academics who are inspecting each other’s courses, I know of at least 12 people in my own University taking MOOCs of various kinds to see what they’re like, and we have the problem that we are measuring people who are merely coming in to have a look around and are probably not as interested in the actual course. Until we can actually shift MOOC demography to match that of our real students, we are always going to have our measurements affected by these observers. The observers might not mind being heavily monitored and observed, but real students might. Either way, numbers are not the real answer here – they show us what but there is still too much uncertainty in the why and the how.

- Schrödinger’s MOOC: Oh, that poor reductio ad absurdum cat. Does the nature of the observer change the behaviour of the MOOC and force it to resolve one way or another (successful/unsuccessful)? If so, how and when? Does the fact of observation change the course even more than just in enrolments and uncertainty of validity of figures? The clickstream data tells us that the forums are overwhelmingly important to students, with 90% of people who viewed threads without commenting, and only 3% of total students enrolled every actually posted anything in a thread. What was the make-up of that 3% and was it actual students or the over-qualified observers who then provided an environment that 90% of their peers found useful?

- Numbers need context and unasked questions give us no data: As one example, the authors of the study were puzzled that so few people had logged in from China, which surprised them. Anyone who has anything to do with network measurement is going to be aware that China is almost always an outlier in network terms. My blog, for example, has readers from around the world – but not China. It’s also important to remember that any number of Chinese network users will VPN/SSH to hosts outside China to enjoy unrestricted search and network access. There may have been many Chinese people (who didn’t self-identify for obvious reasons) who were using proxies from outside China. The numbers on this particular part of the study do not make sense unless they are correctly contextualised. We also see a lack of context in the reporting on why people were doing the course – the numbers for why people were doing it had to be augmented from comments in the forum that people ‘wanted to see if they could make it through an MIT course’. Why wasn’t that available from the initial questions?

- We don’t know what pass/fail is going to look like in this environment. I can’t base any MOOC plans of my own on how people respond to a MIT-branded course but it is important to note that MIT’s approach was far more than “watch and scratch”, as is reflected by their educational design in providing various forms of materials, discussions forums, homework and labs. But still, 155,000 people signed up for this and only 7,000 received certificates. 2/3 of people who registered then went on to do nothing. I don’t think that we can treat a success rate of less than 5% as a success rate. Even where we say that 2/3 dropped out, this still equates to a pass rate under 14%. Is that good? Is that bad? Taking everything into account from above, my answer is “We don’t know.” If we get 17% next time, is that good or bad? How do we make this better?

- The drivers are often wrong. Several US universities have gone on the record to complain about undermining their colleagues and have refused to take part in MOOC-related activities. The reasons for this vary but the greatest fear is that MOOCs will be used to reduce costs by replacing existing lecturing staff with a far smaller group and using MOOCs to handle the delivery. From a financial argument, MOOCs are astounding – 155,000 people contacted for the cost of a few lecturers. Contrast that with me teaching a course to 100 students. If we look at it from a quality perspective, and dealing with all of the points so far, we have no argument to say that MOOCs are as good as our good teaching – but we do know that they are easily as good as our bad teaching. But from a financial perspective? MOOC is king. That is, however, not how we guarantee educational quality. Of course, when we scale, we can maintain quality by increasing resources but this runs counter to a cost-saving argument so we’re almost automatically being prevented from doing what is required to make the large scale course work by the same cost driver that led to its production in the first place!

- There are a lot of statements but perhaps not enough discussion. These are trying times for higher education and everyone wants an edge, more students, higher rankings, to keep their colleagues and friends in work and, overall, to do the right thing for their students. Senior management, large companies, people worried about money – they’re all talking about MOOCs as if they are an accepted substitute for traditional approaches – at the same time as we are in deep discussion about which of the actual traditional approaches are worthwhile and which new approaches are going to work better. It’s a confusing time as we try to handle large-scale adoption of blended learning techniques at the same time people are trying to push this to the large scale.

I’m worried that I seem to be spending most of my time explaining what MOOCs are to people who are asking me why I’m not using a MOOC. I’m even more worried when I am still yet to see any strong evidence that MOOCs are going to provide anything approaching the educational design and integrity that has been building for the past 30 years. I’m positively terrified when I see corporate providers taking over University delivery before we have established actual measurable quality and performance guidelines for this incredibly important activity. I’m also bothered by statements found at the end of the study, which was given prominence as a pull quote:

[The students] do not follow the norms and rules that have governed university courses for centuries nor do they need to.

I really worry about this because I haven’t yet seen any solid evidence that this is true, yet this is exactly the kind of catchy quote that is going to be used on any number of documents that will come across my desk asking me when I’m going to MOOCify my course, rather than discussing if and why and how we will make a transition to on-line blended learning on the massive scale. The measure of MOOC success is not the number of enrolees, nor is it the number of certificates awarded, nor is it the breadth of people who sign up. MOOCs will be successful once we have worked out how to use this incredibly high potential approach to teaching to deliver education at a suitably high level of quality to as many people as possible, at a reduced or even near-zero cost. The potential is enormous but, right now, so is the risk!

Why You Won’t Finish This Post

Posted: June 10, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, design, education, educational problem, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, universal principles of design 3 CommentsA friend of mine on Facebook posted a link to a Slate article entitled “You Won’t Finish This Article: Why people online don’t read to the end” and it’s told me everything that I’ve been doing wrong with this blog for about the last 410 hours. Now, this doesn’t even take into account that, by linking to something potentially more interesting on a well-known site, I’ve now buried the bottom of this blog post altogether because a number of you will follow the link and, despite me asking it to appear in a new window, you will never come back to this article. (This has quite obvious implications for the teaching materials we put up, so it’s well worth a look.)

Now, on the off-chance that you did come back (hi!), we have to assume that you didn’t read all of the linked article (if you read any at all) because 28% of you ‘bounced’ immediately and didn’t actually read much at all of that page – you certainly didn’t scroll. Almost none of you read to the bottom. What is, however, amusing is that a number of you will have either Liked or forwarded a link to one or both of these pages – never having stepped through or scrolled once, but because the concept at the start looks cool. Of course, according the Slate analysis, I’ve lost over half my readers by now. Of course, this does assume the Slate layout, where an image breaks things up and forces people to scroll through. So here’s an image that will discourage almost everyone from continuing. However, it is a pretty picture:

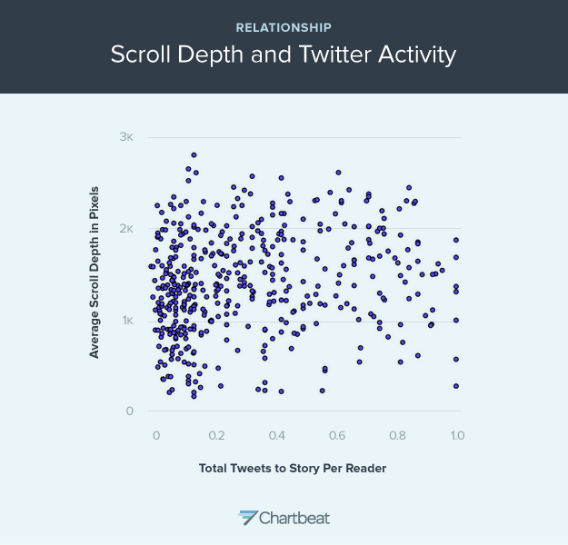

This graph shows the relationship between scroll depth and Tweet (From Slate and courtesy of Chartbeat)

What it says is that there is not an enormously strong correlation between depth of reading and frequency of tweet. So, the amount that a story is read doesn’t really tell you how much people will want to (or actually) share it. Overall, the Slate article makes it fairly clear that unless I manage to make my point in the first paragraph, I have little chance of being read any further – but if I make that first paragraph (or first images) appealing enough, any number of people will like and share it.

Of course, if people read down this far (thanks!) then they will know that I secretly start advocating the most horrible things known to humanity so, when someone finally follows their link and miraculously reads down this far, survives the Slate link out, and doesn’t end up mired in the picture swamp above, they will discover…

Oh, who am I kidding. I’ll just come back and fill this in later.

(Having stolen a time machine, I can now point out that this is yet another illustration of why we need to be thoughtful about what our students are going to do in response to on-line and hyperlinked materials rather than what we would like them to do. Any system that requires a better human, or a human to act in a way that goes against all the evidence we have of their behaviour, requires modification.)

The Kids are Alright (within statistical error)

Posted: April 21, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: blogging, community, data visualisation, design, education, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, reflection, thinking, tools 3 CommentsYou may have seen this quote, often (apparently inaccurately) attributed to Socrates:

“The children now love luxury; they have bad manners, contempt for authority; they show disrespect for elders and love chatter in place of exercise. Children are now tyrants, not the servants of their households. They no longer rise when elders enter the room. They contradict their parents, chatter before company, gobble up dainties at the table, cross their legs, and tyrannize their teachers.” (roughly 400BC)

Apparently this is either a paraphrase of Aristophanes or misquoted Plato – like all things attributed to Socrates, we have to remember that we don’t have his signature to any of them. However, it doesn’t really matter if Socrates said it because not only did Hesiod say something in 700BC:

“I see no hope for the future of our people if they are dependent on frivolous youth of today, for certainly all youth are reckless beyond words… When I was young, we were taught to be discreet and respectful of elders, but the present youth are exceedingly wise [disrespectful] and impatient of restraint”

And then we have Peter the Hermit in 1274AD:

“The world is passing through troublous times. The young people of today think of nothing but themselves. They have no reverence for parents or old age. They are impatient of all restraint. They talk as if they knew everything, and what passes for wisdom with us is foolishness with them. As for the girls, they are forward, immodest and unladylike in speech, behavior and dress.”

(References via the Wikiquote page of Socrates and a linked discussion page.)

Let me summarise all of this for you:

You dang kids! Get off my lawn.

As you know, I’m a facty-analysis kind of guy so I thought that, if these wise people were correct and every generation is steadily heading towards mental incapacity and moral turpitude, we should be able to model this. (As an aside, I love the word turpitude, it sounds like the state of mind a turtle reaches after drinking mineral spirits.)

So let’s do this, let’s assume that all of these people are right and that the youth are reckless, disrespectful and that this keeps happening. How do we model this?

It’s pretty obvious that the speakers in question are happy to set themselves up as people who are right, so let’s assume that a human being’s moral worth starts at 100% and that all of these people are lucky enough to hold this state. Now, since Hesiod is chronologically the first speaker, let’s assume that he is lucky enough to be actually at 100%. Now, if the kids aren’t alright, then every child born will move us away from this state. If some kids are ok, then they won’t change things. Of course, every so often we must get a good one (or Socrates’ mouthpiece and Peter the Hermit must be aliens) so there should be a case for positive improvement. But we can’t have a human who is better than 100%, work with me here, and we shall assume that at 0% we have the worst person you can think of.

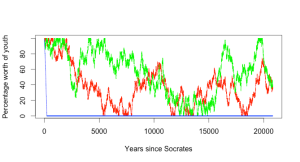

What we are now modelling is a random walk, starting at 100 and then adding some combination of -1, 0 or 1 at some regular interval. Let me cut to the chase and show you what this looks like, when modelled. I’ve assumed, for ease of modelling, that we make the assessment of the children every year and we have at most a 1 percentile point shift in that year, whatever other assumptions I made. I’ve provided three different models, one where the kids are terrible – we choose very year from no change or a negative shift. The next model is that the kids have some hope but sometimes do nothing, and we choose from an improvement, no change or steady moral decline! The final model is one where we either go up or down. Let’s look at a random walk across all three models over the span of years from 700BC to today:

As you can see, if we take the dire predictions of the next generation as true, then it is only a few hundred years before everything collapses. However, as expected, random walks over this range move around and hit a range of values. (Right now, you should look up Gambler’s Ruin to see why random walks are interesting – basically, over an infinite time, you’d expect to hit all of the values in the range from 0 to 100 an infinite number of times. This is why gamblers with small pots of money struggle against casinos with effectively infinite resources. Maths.)

But we know that the ‘everything is terrible’ model doesn’t work because both Socrates and Peter the Hermit consider themselves to be moral and both lived after the likely ‘decline to zero’ point shown in the blue line. But what would happen over longer timeframes? Let’s look at 20,000 and 200,000 years respectively. (These are separately executed random walks so the patterns will be different in each graph.)

What should be apparent, even with this rather pedantic exploration of what was never supposed to be modelled is that, even if we give credence to these particular commentators and we accept that there is some actual change that is measurable and shows an improvement or decline between generations, the negative model doesn’t work. The longer we run this, the more it will look like the noise that it is – and that is assuming that these people were right in the first place.

Personally, I think that the kids of this generation are pretty much the same as the one before, with some different adaptation to technology and societal mores. Would I have wasted time in lectures Facebooking if I had the chance? Well, I wasted it doing everything else so, yes, probably. (Look around your next staff meeting to see how many people are checking their mail. This is a technological shift driven by capability, not a sign of accelerating attention deficit.) Would I have spent tons of times playing games? Would I? I did! They were just board, role-playing and simpler computer games. The kids are alright and you can see that from the graphs – within statistical error.

Every time someone tells me that things are different, but it’s because the students are not of the same calibre as the ones before… well, I look at these quotes over the past 2,500 and I wonder.

And I try to stay off their lawn.

Tell us we’re dreaming.

Posted: April 21, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, education, Generation Why, higher education, reflection, resources, thinking, work/life balance, workload 2 CommentsI recently read an opinion piece in the Australian national newspaper, the conveniently named “The Australian”, on funding school reform. The piece, entitled “School Reform must be funded” and sub-titled “But maybe we need fewer academics thinking up ways to spend our taxes”, written by Cassandra Wilkinson, identified that the coming cuts to higher education because of the apparent impossibility of paying for school reforms in any other way. No-one, sensible, is arguing that the school cuts can come out of thin air, I make explicit reference to realities such as this in my previous post, but it does appear that Cassandra is attempting to place the blame squarely on the shoulders of the academics, for this sorry state of affairs (“the growing influence of the university sector on early childhood and school education is partly responsible for the now necessary cuts to higher education.”, from the article).

It is the professionalisation of teaching, and the intervention of education academics to convince governments that early educational investment, potentially at the expense of the family unit’s role in child rearing, that has convinced governments that money must be spent here – therefore, it is our fault that our argument is leading to money coming out of our pockets. I cannot think of a more amazing piece of victim blaming, recently, but then again I generally don’t read the opinion section of The Australian!

Now, you may immediately say “You must be quoting her out of context”, here is another extract from this rather short opinion piece:

“In addition to the public costs being generated by education academics, we have public health academics driving an expensive “preventative health” agenda that includes mental health checks for kids and public advertising about the calorie content of pizza; safety academics driving up the cost of road building and tripling the price of trampolines, which now come with fencing and crash mats; and sustainability academics driving up the cost of housing.”

Not only are people concerned about education driving up the cost of education but we have increased all other prices through our short-sighted adherence to preventative health, safety and sustainability! I keep thinking that Wilkinson, who has some quiet excellent social project credentials if I have researched the correct Cassandra Wilkinson, must be making a satirical comment here but, either my humour is failing (entirely possible), she has been edited (entirely possible) or she is completely serious and we in higher education have brought doom upon our heads by dint of doing our job. The piece finishes with:

“It may well be that the real efficiency savings will derive from a university sector employing slightly fewer academics to dream up new ways for governments to spend taxpayers money.”

and whether this is intended to be satire or not, this statement does raise my hackles.

Right now, most of the academics I know are trying to dream up ways to meet our obligations to our students in terms of a high-quality, useful and valuable education under existing restrictions. The only tax spending we’re trying to do is on the things that we can barely afford to do on the monies we get. I’m assuming that Cassandra is being satirical but is just not very good at it – or is assuming the role of her namesake, in that no-one will actually take her seriously, which is a shame as the approach that she seems to be supporting is not just saying that the only place this money can come from is higher ed, but that we should shut up because of how much we’re costing decent, family-centered Australians. If only I had that many column inches in a large-scale distribution paper to put my case that, maybe, people should stop talking about what they think we’re doing, or their fuzzy memories of old Uni days and bad movies, and come down and see what we’re doing now. Shadow me for a month. Bring running shoes. But, hey, maybe I’m just lazy, soft and dreamy. How would I know?

The rich dream of luxuries, the poor dream of staples. We are dreaming of having enough to do our jobs adequately and these are not the dreams of rich people.

Maybe I’m just too tired right now to see her humour in all of this. I seriously hope that I’ve just got the wrong end of the stick, because if this is what the social progressives are saying, then we may as well close up shop now.

A Brief Aside On Blogging

Posted: March 24, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, blogging, community, education, higher education, reflection Leave a commentI ran into someone last night was a reader of my blog (Hi, Maria) and, as always, it was slightly strange to run into someone who had been reading my rantings for over a year before finally meeting me in the flesh. Although I always get very self-conscious when it happens, the real benefit is the reminder that it is not just spam bots and ad robots that are reading my feed – there are real readers out there beyond the small group who are commenting (and thank you for your comments!).

As you can see, I was reminded to start blogging again after a long silence and the occasional post. Now I am writing – two posts in one day!. Interesting – it seems that appreciation of worth provides motivation…

Who would have thought it?

Grace.

Posted: January 29, 2013 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, education, educational problem, higher education, in the student's head, measurement, principles of design, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, work/life balance 1 CommentA friend sent me a link to this excellent piece on the importance of grace, in terms of your own appreciation of yourself and in your role as a teacher. Thank you, A! Here is the link:

The Lesson of Grace in Teaching

“…to hear from my own professor, whom I really love and admire, at a time when I felt ashamed of my intelligence and thus unworthy of his friendship, that I wasn’t just a student in a seat, not just a letter grade or a number on my transcript, but a valuable person who he wants to know on a personal level, was perhaps the most incredible moment of my college career.”

Doo de doo dooooo, doo de doo doo dooooo.

Posted: January 1, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, education, higher education, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, universal principles of design, vonnegut, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentSome of you will recognise the title of this post as the opening ‘music’ of the Europe song, “The Final Countdown”. I wasn’t sure what to call this post because it was the final component of a year long cycle that begin with some sketchy diagrams and a sketchier plan and has seen several different types of development over time. It is not, however, the final post on this blog as I intend to keep blogging but, from this post forwards, I will no longer require myself to provide at least one new post for every day.

This is, perhaps, just as well, because I am already looking over 2013 and realising that my ‘free project’ space is now completely occupied until July. Despite my intentions to travel less, I am in the US twice before the middle of March and have several domestic trips planned as well. And this is a reminder of everything that I’ve been trying to come to terms with in writing this blog and talking about my students, myself, and our community: I can talk about things and deal with them rationally in my head, but that doesn’t mean that I always act on them.

In retrospect, it has been a successful year and I have been able to produce more positive change in 2012 then probably in the sum of my working contributions up until that point. However, I am not in as good a shape as I was at the start of the year, for a variety of reasons, so when I say that my ‘free project’ space is full, I mean that I have fewer additional things to do but I am deliberately allocating less of my personal time to do them. In 2013, family and friends come first, then my projects, then my required work. Why? Because I will always find a way to do the work that I’m supposed to do, but if I start with that I can use all of my time to do that, whereas if I invert it, I have to be more efficient and I’m pretty confident that I can still get it done. After all, next year I’ll have at least an extra hour or two a day from not blogging.

Let’s not forget that this blogging project has consumed somewhere in the region of 350-400 hours of my time over the year, and that’s probably an underestimate. 400 hours is ten working weeks or just under 17 days of contiguous hours. Was my blog any better for being daily? Probably not. Could I be far more flexible and agile with my time if I removed the daily posting requirement? Of course – and so, away it goes. (So it goes, Mr Vonnegut.) The value to me of this activity has been immense – it has changed the way that I think about things and I have a far greater basis of knowledge from which I can discuss important aspects of learning and teaching. I have also discovered how little I know about some things but at least I know that they exist now! The value to other people is more debatable but given that I know that at least some people have found use in it, then it’s non-zero and I can live with that. Recalling Kurt Vonnegut again, and his book “Timequake”, I always saw this blog as a place where people could think “Oh, me too!” as I stumble my way through complicated ideas and try to comprehend the developed notions of clever people.

“Many people need desperately to receive this message: ‘I feel and think much as you do, care about many of the things you care about, although most people do not care about them. You are not alone.'” (Vonnegut, Timequake, 1997)

I never really thought much about the quality of this blog, but I was always concerned about the qualities of it. I wanted it to be inclusive, reliable, honest, humble, knowledgable, useful and welcoming. Looking back, I achieved some of that some of the time and, at other times, well, I’m a human. Some days I was angrier than others but I like to think it was about important things. Sexism makes me angry. Racism makes me angry. The corruption of science for political ends makes me angry. Deliberate ignorance makes me angry. Inequity and elitism make me angry. I hope, however, the anger was a fuel for something better, burning to lift something up that carried a message that wasn’t just pure anger. If, at any stage, all I did was combine oxygen and kerosene on the launch pad and burn the rocket, then I apologise, because I always wanted to be more useful than that.

This is not the end of the blog, but it’s the end of one cycle. It’s like a long day at the beach. You leap out of bed as the sun is coming up, grab some fruit and run down to the water, still warm from the late summer currents and the hot wind that blows across it, diving in to swim out and look back at the sand as it lights up. Maybe you grab your fishing rod and spend an hour or two watching the float bob along the surface, more concerned with talking to your friend or drinking a beer than actually catching a fish, because it’s just such a nice day to be with people. Lunch is sandy sandwiches, eaten between laughs in the gusty breeze that lifts up the beach and tries to jam a big handful of grains into every bite, so you juggle it and the tomato slides out, landing on your lap. That’s ok, because all you have to do is to dive back into the water and you’re clean again. The afternoon is beach cricket, squinting even through sunglasses as some enthusiastic adult hits the ball for a massive 6 that requires everyone to search for it for about 15 minutes, then it’s some cold water and ice creams. Heading back that night, and it’s a long day in an Australian summer, you’re exhausted, you’re spent. You couldn’t swim another stroke, eat another chip or run for another ball if you tried. You’ll eat something for dinner and everyone will mumble about staying up but the day is over and, in an hour or so, everyone will be asleep. You might try and stay up because there’s so much to do but the new day starts tomorrow. Or, worst case, next summer. It’s not the end of the beach. It’s just the end of one day.

Firstly, of course, I want to thank my wife who has helped me to find the time I needed to actually do this and who has provided a very patient ear when I am moaning about that most first world of problems: what is my blog theme for today. The blog has been a part of our lives every day for 1-2 hours for an entire year and that requires everyone in the household to put in the effort – so, my most sincere gratitude to the amazing Dr K. There’s way I could have done any of this without you.

For everyone who is not my wife, thank you for reading and being part of what has been a fascinating journey. Thank you for all of your comments, your patience, your kindness and your willingness to listen. I hope that you have a very happy and prosperous New Year. Remember what Vonnegut said; that people need to know, sometimes, that they are not alone.

I’ll see you tomorrow.

WordPress Still Don’t Quite Get It

Posted: December 31, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, blogging, education, higher education, thinking, tools Leave a commentSome time ago, I logged a report to WordPress that one of their ‘incentive’ messages for completing and posting a blog post was a highly dismissive Capote quote about Kerouac’s writing of “On the Road” – “That’s not writing, that’s typing”. I felt that this was not the kind of thing that you said to someone as an incentive and, nicely, the people who handled my comment appeared to agree and I haven’t seen it since.

Today they sent me their “Your Year in Review” link which gave me a prettied-up, but not overly informative, set of aggregated statistics for 2012. This one stuck out:

“In 2012, there were 438 new posts, not bad for the first year!”

Not bad? I posted every 20 hours on average across the year and that’s not bad???

I know what they’re trying to say but, seriously, their automated encouragement software needs some work. Of course, the scary question is: what does WordPress consider to be good in terms of posting count? Every 10 hours? Every 5 hours?

Seriously, WordPress people, please start thinking about the throwaway language that you are using to pretend that you know what we’re doing. We are all happily using your site – don’t let bad scripting and automated pseudo-encouragement undo all of the cool things that we can do here!

Thanks for the exam – now I can’t help you.

Posted: December 31, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, tools, universal principles of design, vygotsky, workload 1 CommentI have just finished marking a pile of examinations from a course that I co-taught recently. I haven’t finalised the marks but, overall, I’m not unhappy with the majority of the results. Interestingly, and not overly surprisingly, one of the best answered sections of the exam was based on a challenging essay question I set as an assignment. The question spans many aspects of the course and requires the student to think about their answer and link the knowledge – which most did very well. As I said, not a surprise but a good reinforcement that you don’t have to drill students in what to say in the exam, but covering the requisite knowledge and practising the right skills is often helpful.

However, I don’t much like marking exams and it doesn’t come down to the time involved, the generally dull nature of the task or the repetitive strain injury from wielding a red pen in anger, it comes down to the fact that, most of the time, I am marking the student’s work at a time when I can no longer help him or her. Like most exams at my Uni, this was the terminal examination for the course, worth a substantial amount of the final marks, and was taken some weeks after teaching finished. So what this means is that any areas I identify for a given student cannot now be corrected, unless the student chooses to read my notes in the exam paper or come to see me. (Given that this campus is international, that’s trickier but not impossible thanks to the Wonders of Skypenology.) It took me a long time to work out exactly why I didn’t like marking, but when I did, the answer was obvious.

I was frustrated that I couldn’t actually do my job at one of the most important points: when lack of comprehension is clearly identified. If I ask someone a question in the classroom, on-line or wherever, and they give me an answer that’s not quite right, or right off base, then we can talk about it and I can correct the misunderstanding. My job, after all, is not actually passing or failing students – it’s about knowledge, the conveyance, construction and quality management thereof. My frustration during exam marking increases with every incomplete or incorrect answer I read, which illustrates that there is a section of the course that someone didn’t get. I get up in the morning with the clear intention of being helpful towards students and, when it really matters, all I can do is mark up bits of paper in red ink.

Quickly, Jones! Construct a valid knowledge framework! You’re in a group environment! Vygotsky, man, Vygotsky!

A student who, despite my sweeping, and seeping, liquid red ink of doom, manages to get a 50 Passing grade will not do the course again – yet this mark pretty clearly indicates that roughly half of the comprehension or participation required was not carried out to the required standard. Miraculously, it doesn’t matter which half of the course the student ‘gets’, they are still deemed to have attained the knowledge. (An interesting point to ponder, especially when you consider that my colleagues in Medicine define a Pass at a much higher level and in far more complicated ways than a numerical 50%, to my eternal peace of mind when I visit a doctor!) Yet their exam will still probably have caused me at least some gnashing of teeth because of points missed, pointless misstatement of the question text, obscure song lyrics, apologies for lack of preparation and the occasional actual fact that has peregrinated from the place where it could have attained marks to a place where it will be left out in the desert to die, bereft of the life-giving context that would save it from such an awful fate.

Should we move the exams earlier and then use this to guide the focus areas for assessment in order to determine the most improvement and develop knowledge in the areas in most need? Should we abandon exams entirely and move to a continuous-assessment competency based system, where there are skills and knowledge that must be demonstrated correctly and are practised until this is achieved? We are suffering, as so many people have observed before, from overloading the requirement to grade and classify our students into neatly discretised performance boxes onto a system that ultimately seeks to identify whether these students have achieved the knowledge levels necessary to be deemed to have achieved the course objectives. Should we separate competency and performance completely? I have sketchy ideas as to how this might work but none that survive under the blow-torches of GPA requirements and resource constraints.

Obviously, continuous assessment (practicals, reports, quizzes and so on) throughout the semester provide a very valuable way to identify problems but this requires good, and thorough, course design and an awareness that this is your intent. Are we premature in treating the exam as a closing-off line on the course? Do we work on that the same way that we do any assignment? You get feedback, a mark and then more work to follow-up? If we threw resourcing to the wind, could we have a 1-2 week intensive pre-semester program that specifically addressed those issues that students failed to grasp on their first pass? Congratulations, you got 80%, but that means that there’s 20% of the course that we need to clarify? (Those who got 100% I’ll pay to come back and tutor, because I like to keep cohorts together and I doubt I’ll need to do that very often.)

There are no easy answers here and shooting down these situations is very much in the fish/barrel plane, I realise, but it is a very deeply felt form of frustration that I am seeing the most work that any student is likely to put in but I cannot now fix the problems that I see. All I can do is mark it in red ink with an annotation that the vast majority will never see (unless they receive the grade of 44, 49, 64, 74 or 84, which are all threshold-1 markers for us).

Ah well, I hope to have more time in 2013 so maybe I can mull on this some more and come up with something that is better but still workable.

Thinking about teaching spaces: if you’re a lecturer, shouldn’t you be lecturing?

Posted: December 30, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design, vygotsky Leave a commentI was reading a comment on a philosophical post the other day and someone wrote this rather snarky line:

He’s is a philosopher in the same way that (celebrity historian) is a historian – he’s somehow got the job description and uses it to repeat the prejudices of his paymasters, flattering them into thinking that what they believe isn’t, somehow, ludicrous. (Grangousier, Metafilter article 123174)

Rather harsh words in many respects and it’s my alteration of the (celebrity historian)’s name, not his, as I feel that his comments are mildy unfair. However, the point is interesting, as a reflection upon the importance of job title in our society, especially when it comes to the weighted authority of your words. From January the 1st, I will be a senior lecturer at an Australian University and that is perceived differently where I am. If I am in the US, I reinterpret this title into their system, namely as a tenured Associate Professor, because that’s the equivalent of what I am – the term ‘lecturer’ doesn’t clearly translate without causing problems, not even dealing with the fact that more lecturers in Australia have PhDs, where many lecturers in the US do not. But this post isn’t about how people necessarily see our job descriptions, it’s very much about how we use them.

In many respects, the title ‘lecturer’ is rather confusing because it appears, like builder, nurse or pilot, to contain the verb of one’s practice. One of the big changes in education has been the steady acceptance of constructivism, where the learners have an active role in the construction of knowledge and we are facilitating learning, in many ways, to a greater extent than we are teaching. This does not mean that teachers shouldn’t teach, because this is far more generic than the binding of lecturers to lecturing, but it does challenge the mental image that pops up when we think about teaching.

If I asked you to visualise a classroom situation, what would you think of? What facilities are there? Where are the students? Where is the teacher? What resources are around the room, on the desks, on the walls? How big is it?

Take a minute to do just this and make some brief notes as to what was in there. Then come back here.

It’s okay, I’ll still be here!