The 1-Year Degree – what’s your reaction?

Posted: July 30, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: constructive student pedagogy, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, workload 2 CommentsI’m going to pose a question and I’d be interested in your reaction.

“Is there a structure and delivery mechanism that could produce a competent professional graduate from a degree course such as engineering or computer science, which takes place over a maximum of 12 months including all assessment, without sacrificing quality or content?”

What was your reaction? More importantly, what is the reasoning behind your reaction?

For what it’s worth my answer is “Not with our current structures but, apart from that, maybe.” which is why one of my side projects is an attempt to place an entire degree’s worth of work into a 12-month span as a practice exercise for discussing the second and third year curriculum review that we’re holding later on this year.

Our ‘standard’ estimate for any normal degree program is that a student is expected to have a per-semester load of four courses (at 3 units a course, long story) and each of these courses will require 156 hours from start to finish. (This is based on 10 hours per week, including contact and non-contact, and roughly 36 hours for revision towards examination or the completion of other projects.) Based on this estimate, and setting up an upper barrier of 40 hours/week, for all of the good research-based reasons that I’ve discussed previously, there is no way that I can just pick up the existing courses and drop them into a year. A three-year program has six semesters, with four courses per semester, which gives an hour burden of 24*156 = 3,744. At 40 hours per week, we’d need 93.6 weeks (let’s call that 94), or 1.8 years.

But, hang on, we already have courses that are 6-unit and span two semesters – in fact, we have enormous projects for degree programs like Honours that are worth the equivalent of four courses. Interestingly, rather than having an exam every semester, these have a set of summative and formative assignments embedded to allow the provision of feedback and the demonstration of knowledge and skill acquisition – does this remove the need to have 36 hours for exam study for each semester if we build the assignments correctly?

Let’s assume that it does. Now we have a terminal set of examinations at the end of each year, instead of every semester. Now I have 12 courses at 120 hours each and 12 at 156 hours each. Now we’re down to 3,312 – which is only 1.6 years. Dang. Still not there. But it’s ok, I can see all of you who have just asked “Well, why are you so keen on using examinations if you’re happy with summative assignments testing concepts as you go and then building in the expectation of this knowledge in later modules?” Let’s drop the exam requirement even further to a final set of professional level assessment criteria, carried out at the end of the degree to test high-level concepts and advanced skills. Now, of the 24 courses that a student sits, almost all assessment work has moved into continuous assessment mode, rich in feedback, with summative checkpoints and a final set of examinations as part of the four capstone courses at the end. This gives us 3,024 hours – about 1.45 years.

But this is also ignoring that the first week of many of these courses is required revision after some 6-18 weeks of inactivity as the students go away to summer break or home for various holidays. Let’s assume even further that, with the exception of the first four courses that they do, that we build this continuously so that skills and knowledge are reinforced as micro slides, scattered throughout the work, supported with recordings, podcasts, notes, guides and quick revision exercises in the assessment framework. Now I can slice maybe 5 hours off 20 of the courses (the last 20) – cutting me down by another 100 hours and that’s half a month saved, down to 1.4 years.

Of course, I’m ignoring a lot of issues here. I’m ignoring the time it takes someone to digest information but, having raised that, can you tell me exactly how long it takes a student to learn a new concept? This is a trick question as the answer generally depends upon the question “how are you teaching them?” We know that lectures are one of the worst ways to transfer information, with A/V displays, lectures and listening all having a retention rate less than 40%. If you’re not retaining, your chances of learning something are extremely low. At the same time, somewhere between 30-50% of the time that we’re allocating to those courses we already teach are spent in traditional lectures – at time of writing. We can improve retention (of both knowledge and students) when we use group work (50% and higher for knowledge) or get the students to practice (75%) or, even better, instruct someone else (up to 90%). If we can restructure the ’empty’ or ‘low transfer’ times into other activities that foster collaboration or constructive student pedagogy with a role transfer that allows students to instruct each other, then we can potentially greatly improve our usage of time.

If we use this notion and slice, say, 20 hours from each course because we can get rid of that many contact hours that we were wasting and get the same, if not better, results, we’re down to 2,444 hours, about 1.18 years. And I haven’t even started looking at the notion of concept alignment, where similar concepts are taught across two different concepts and could be put in one place, taught once, consistently and then built upon for the rest of the course. Suddenly, with the same concepts and a potentially improved educational design – we’re looking the 1-year degree in the face.

Now, there will be people who will say “Well, how does the student mature in this time? That’s only one year!” to which my response is “Well, how are you training them for maturity? Where are the developing exercises? The formative assessment based on careful scaffolding in societal development and intellectual advancement?” If the appeal of the three-year degree is that people will be 19-20 when they graduate, and this is seen as a good thing, then we solve this problem for the 1-year degree by waiting two years before they start!

Having said all of this, and believing that a high quality 1-year degree is possible, let me conclude by saying that I think that it is a terrible idea! University is more than a sequence of assessments and examinations, it is a culture, a place for intellectual exploration and the formation of bonds with like-minded friends. It is not a cram school to turn out a slightly shell-shocked engineer who has worked solidly, and without respite, for 52 weeks. However, my aim was never actually to run a course in a year, it was to see how I could restructure a course to be able to more easily modularise it, to break me out of the mental tyranny of a three- or four-year mandate and to focus on learning outcomes, educational design and sound pedagogy. The reason that I am working on this is so that I can produce a sound course structure with which students can engage, regardless of whether they are full-time or not, clearly outlining dependency and requirements. Yes, if we break this up into part-time, we need to add revision modules back in – but if we teach it intensively (or on-line) then those aren’t required. This is a way to give students choice and the freedom to come in at any age, with whatever time they have, but without sacrificing the quality of the underlying program. This is a bootstrap program for a developing nation, a quick entry point for people who had to go to work – this is making up for decades of declining enrolments in key areas.

This is going on a war footing against the forces of ignorance.

There are many successful “Open” universities that use similar approaches but I wanted to go through the exercise myself, to allow me the greatest level of intellectual freedom while looking at our curriculum review. Now, I feel that I can focus on Knowledge Areas for my specifics and on the program as a whole, freed of the binding assumption that there is an inevitable three-year grind ahead for any student. Perhaps one of the greatest benefits for me is the thought that, for students who can come to us for three years, I can put much, much more into the course if they have the time – and these things, of interest, regarding beauty, of intellectual pursuits, can replace some of the things that we’ve lost over the years in the last two decades of change in University.

Grand Challenges and the New Car Smell

Posted: July 26, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: ALTA, community, curriculum, data visualisation, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, student perspective, teaching approaches Leave a commentIt has been a crazy week so far. In between launching the new course and attending a number of important presentations, our Executive Dean, Professor Peter Dowd, is leaving the role after 8 years and we’re all getting ready for the handover. At time of writing, I’m sitting in an airport lounge in Adelaide Airport waiting for my flight to Melbourne to go and talk about the Learning and Teaching Academy of which I’m a Fellow so, given that my post queue is empty and that I want to keep up my daily posting routine, today’s post may be a little rushed. (As one of my PhD students pointed out, the typos are creeping in anyway, so this shouldn’t be too much of a change. Thanks, T. 🙂 )

The new course that I’ve been talking about, which has a fairly wide scope with high performing students, has occupied five hours this week and it has been both very exciting and a little daunting. The student range is far wider than usual: two end-of-degree students, three start-of-degree students, one second year and one internal exchange student from the University of Denver. As you can guess, in terms of learning design, this requires me to have a far more flexible structure than usual and I go into each activity with the expectation that I’m going to have to be very light on my feet.

I’ve been very pleased by two things in the initial assessment: firstly, that the students have been extremely willing to be engage with the course and work with me and each other to build knowledge, and secondly, that I have the feeling that there is no real ‘top end’ for this kind of program. Usually, when I design something, I have to take into account our general grading policies (which I strongly agree with) that are not based on curve grading and require us to provide sufficient assessment opportunities and types to give students the capability to clearly demonstrate their ability. However, part of my role is pastoral, so that range of opportunities has to be carefully set so that a Pass corresponds to ‘acceptable’ and I don’t set the bar so high that people pursuing a High Distinction (A+) don’t destroy their prospects in other courses or burn out.

I’ve stressed the issues of identity and community in setting up this course, even accidentally referring to the discipline as Community Science in one of my intro slides, and the engagement level of the students gives me the confidence that, as a group, they will be able to develop each other’s knowledge and give them some boosting – on top of everything and anything that I can provide. This means that the ‘top’ level of achievements are probably going to be much higher than before, or at least I hope so. I’ve identified one of my roles for them as “telling them when they’ve done enough”, much as I would for an Honours or graduate student, to allow me to maintain that pastoral role and to stop them from going too far down the rabbit hole.

Yesterday, I introduced them to R (statistical analysis and graphical visualisation) and Processing (a rapid development and very visual programming language) as examples of tools that might be useful for their projects. In fairly short order, they were pushing the boundaries, trying new things and, from what I could see, enjoying themselves as they got into the idea that this was exploration rather than a prescribed tool set. I talked about the time burden of re-doing analysis and why tools that forced you to use the Graphical User Interface (clicking with the mouse to move around and change text) such as Excel had really long re-analysis pathways because you had to reapply a set of mechanical changes that you couldn’t (easily) automate. Both of the tools that I showed them could be set up so that you could update your data and then re-run your analysis, do it again, change something, re-run it, add a new graph, re-run it – and it could all be done very easily without having to re-paste Column C into section D4 and then right clicking to set the format or some such nonsense.

It’s too soon to tell what the students think because there is a very “new car smell” about this course and we always have the infamous, if contested, Hawthorne Effect, where being obviously observed as part of a study tends to improve performance. Of course, in this case, the students aren’t part of an experiment but, given the focus, the preparation and the new nature – we’re in the same territory. (I have, of course, told the students about the Hawthorne Effect in loose terms because the scope of the course is on solving important and difficult problems, not on knee-jerk reactions to changing the colour of the chair cushions. All of the behaviourists in the audience can now shake their heads, slowly.)

Early indications are positive. On Monday I presented an introductory lecture laying everything out and then we had a discussion about the course. I assigned some reading (it looked like 24 pages but was closer to 12) and asked students to come in with a paragraph of notes describing what a Grand Challenge was in their own words, as well as some examples. The next day, less than 24 hours after the lecture, everyone showed up and, when asked to write their description up on the white board, all got up and wrote it down – from their notes. Then they exchanged ideas, developed their answers and I took pictures of them to put up on our forum. Tomorrow, I’ll throw these up and ask the students to keep refining them, tracking their development of their understanding as they work out what they consider to be the area of grand challenges and, I hope, the area that they will start to consider “their” area – the one that they want to solve.

If even one more person devotes themselves to solving an important problem to be work then I’ll be very happy but I’ll be even happier if most of them do, and then go on to teach other people how to do it. Scale is the killer so we need as many dedicated, trained, enthusiastic and clever people as we can – let’s see what we can do about that.

Environmental Impact: Iz Tweetz changing ur txt?

Posted: July 25, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: blogging, education, educational problem, educational research, higher education, learning, measurement, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, tools 5 CommentsPlease, please forgive me for the diabolical title but I have been wondering about the effects of saturation in different communication environments and Twitter seemed like an interesting place to start. For those who don’t know about Twitter, it’s an online micro-blogging social media service. Connect to it via your computer or phone and you can put a message in that is up to 140 characters, where each message is called a tweet. What makes Twitter interesting is the use of hashtags and usernames to allow the grouping of these messages by area by theme (#firstworldproblems, if you’re complaining about the service in Business Class, for example) or to respond to someone (@katyperry – Russell Brand, SRSLY?). Twitter has very significant penetration in the celebrity market and there are often “professional” tweeters for certain organisations.

There is a lot more to say about Twitter but what I want to focus on is the maximum number of characters available – 140. This limit was set for compatibility with SMS messages and, unsurprisingly, a lot of abbreviations used in Twitter have come in from the SMS community. I have been restricting myself to ~1,000 words in recent posts (+/-10%, if I’m being honest) and, with the average word length of approximately 5 for English then, by adding spaces and punctuation to take this to 6, you’d expect my posts to be somewhere in the region of 6,000 characters. Anyone who’s been reading this for a while will know that I love long words and technical terms so there’s a possibility that it’s up beyond this. So one of my posts, as the largest Tweets, would take up about 43 tweets. How long would that take the average Twitterer?

Here’s an interesting site that lists some statistics, from 2009 – things will have changed but it’s a pretty thorough snapshot. Firstly, the more followers you have the more you tweet (cause and effect not stated!) but even then, 85% of users update less than once per day, with only 1% updating more than 10 times per day. With the vast majority of users having less than 100 followers (people who are subscribed to read all of your tweets), this makes two tweets per day the dominant activity. But that was back in 2009 and Twitter has grown considerably since then. This article updates things a little, but not in the same depth, and gives us two interesting facts. Firstly, that Twitter has grown amazingly since 2009. Secondly, that event reporting now takes place on Twitter – it has become a news and event dissemination point. This is happening to the extent that a Twitter reported earthquake can expand outwards in the same or slightly less time than the actual earthquake itself. This has become a bit of a joke, where people will tweet about what is happening to them rather than react to the event.

From Twitter’s own blog, March, 2011, we can also see this amazing growth – more people are using Twitter and more messages are being sent. I found another site listing some interesting statistics for Twitter: 225,000,000 users, most tweets are 40 characters long, 40% if users don’t tweet but just read and the average user still has around 100 followers (115 actually). If the previous behaviour patterns hold, we are still seeing an average of two tweets for the majority user who actually posts. But a very large number of people are actually reading Twitter far more than they ever post.

To summarise, millions of people around the world are exposed to hundreds of messages that are 4o characters long and this may be one of their leading sources of information and exposure to text throughout the day. To put this in context, it would take 150 tweets to convey one of my average posts at the 40 character limit and this is a completely different way of reading information because, assuming that the ‘average’ sentence is about 15-20 words, very few of these tweets are going to be ‘full’ sentences. Context is, of course, essential and a stream of short messages, even below sentence length, can be completely comprehensible. Perhaps even sentence fragments? Or three words. Two words? One? (With apologies to Hofstadter!) So there’s little mileage in arguing that tweeting is going to change our semantic framework, although a large amount of what moves through any form of blogging, micro or other, is going to always have its worth judged by external agents who don’t take part in that particular activity and find it wanting. (I blog, you type, he/she babbles.)

But is this shortening of phrase, and our immersion in a shorter sentence structure, actually having an impact on the way that we write or read? Basically, it’s very hard to tell because this is such a recent phenomenon. Early social media sites, including the BBs and the multi-user shared environments, did not value brevity as much as they valued contribution and, to a large extent, demonstration of knowledge. There was no mobile phone interaction or SMS link so the text limit of Twitter wasn’t required. LiveJournal was, if anything, the antithesis of brevity as the journalling activity was rarely that brief and, sometimes, incredibly long. Facebook enforces some limits but provides notes so that longer messages can be formed but, of course, the longer the message, the longer the time it takes to write.

Twitter is an encourager of immediacy, of thought into broadcast, but this particular messaging mode, the ability to globally yell “I like ice cream and I’m eating ice cream” as one is eating ice cream is so new that any impact on overall language usage is going to be hard to pin down. As it happens, it does appear that our sentences are getting shorter and that we are simplifying the language but, as this poster notes, the length of the sentence has shrunk over time but the average word length has only slightly shortened, and all of this was happening well before Twitter and SMS came along. If anything, perhaps this indicates that the popularity of SMS and Twitter reflects the direction of language, rather than that language is adapting to SMS and Twitter. (Based on the trend, the Presidential address of 2300 is going to be something along the lines of “I am good. The country is good. Thank you.”)

I haven’t had the time that I wanted to go through this in detail, and I certainly welcome more up-to-date links and corrections, but I much prefer the idea that our technologies are chosen and succeed based on our existing drives tastes, rather than the assumption that our technologies are ‘dumbing us down’ or ‘reducing our language use’ and, in effect, driving us. I guess you may say I’m a dreamer.

(But I’m not the only one!)

The Early-Career Teacher

Posted: July 24, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, herdsa, higher education, learning, principles of design, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentRecently, I mentioned the Australian Research Council (ARC) grant scheme, which recognises that people who have had their PhDs for less than five years are regarded as early-career researchers (ECRs). ECRs have a separate grant scheme (now, they used to have a different way of being dealt with in the grant application scheme) that recognises the fact that their track records, the number of publications and activity relative to opportunity, is going to be less than that of more seasoned individuals.

What is interesting about this is that someone who has just finished their PhD will have spent (at least) three years, more like four, doing research and, we hope, competent research under guidance for the last two of those years. So, having spent a couple of years doing research, we then accept that it can take up to five years for people to be recognised as being at the same level.

But, for the most part, there is no corresponding recognition of the early-career teacher, which is puzzling given that there is no requirement to meet any teaching standards or take part in any teaching activities at all before you are put out in front of a class. You do no (or are not required to do any) teaching during your PhD in Australia, yet we offer support and recognition of early status for the task that you HAVE been doing – and don’t have a way to recognise the need to build up your teaching.

We discussed ideas along these lines at a high-level meeting that I attended this morning and I brought up the early-career teacher (and mentoring program to support it) because someone had brought up a similar idea for researchers. Mentoring is very important, it was one of the big HERDSA messages and almost everywhere I go stresses this, and it’s no surprise that it’s proposed as a means to improve research but, given the realities of the modern Australian University where more of our budget comes from teaching than research, it is indicative of the inherent focus on research that I need to propose teaching-specific mentoring in reaction to research-specific mentoring, rather than vice versa.

However, there are successful general mentoring schemes where senior staff are paired with more junior staff to give them help with everything that they need and I quite like this because it stresses the nexus of teaching and research, which is supposed to be one of our focuses, and it also reduces the possibility of confusion and contradiction. But let’s return to the teaching focus.

The impact of an early-career teacher program would be quite interesting because, much as you might not encourage a very raw PhD to leap in with a grant application before there was enough supporting track record, you might have to restrict the teaching activities of ECTs until they had demonstrated their ability, taken certain courses or passed some form of peer assessment. That, in any form, is quite confronting and not what most people expect when they take up a junior lectureship. It is, however, a practical way to ensure that we stress the value of teaching by placing basic requirements on the ability to demonstrate skill within that area! In some areas, as well as practical skill, we need to develop scholarship in learning and teaching as well – can we do this in the first years of the ECT with a course of educational psychology, discipline educational techniques and practica to ensure that our lecturers have the fundamental theoretical basis that we would expect from a school teacher?

Are we dancing around the point and, extending the heresy, require something much closer to the Diploma of Education to certify academics as teachers, moving the ECR and the ECT together to give us an Early Career Academic (ECA), someone who spends their first three years being mentored in research and teaching? Even ending up with (some sort of) teaching qualification at the end? (With the increasing focus on quality frameworks and external assessment, I keep waiting for one of our regulatory bodies to slip in a ‘must have a Dip Ed/Cert Ed or equivalent’ clause sometime in the next decade.)

To say that this would require a major restructure in our expectations would be a major understatement, so I suspect that this is a move too far. But I don’t think it’s too much to put limits on the ways that we expose our new staff to difficult or challenging teaching situations, when they have little training and less experience. This would have an impact on a lot of teaching techniques and accepted practices across the world. We don’t make heavy use of Teaching Assistants (TAs) at my Uni but, if we did, a requirement to reduce their load and exposure would immediately push more load back onto someone else. At a time when salary budgets are tight and people are already heavily loaded, this is just not an acceptable solution – so let’s look at this another way.

The way that we can at least start this, without breaking the bank, is to emphasise the importance of teaching and take it as seriously as we take our research: supporting and developing scholarship, providing mentoring and extending that mentoring until we’re sure that the new educators are adapting to their role. These mentors can then give feedback, in conjunction with the staff members, as to what the new staff are ready to take on. Of course, this requires us to carefully determine who should be mentored, and who should be the mentor, and that is a political minefield as it may not be your most senior staff that you want training your teachers.

I am a fairly simple man in many ways. I have a belief that the educational role that we play is not just staff-to-student, but staff-to-staff and student-to-student. Educating our new staff in the ways of education is something that we have to do, as part of our job. There is also a requirement for equal recognition and support across our two core roles: learning and teaching, and research. I’m seeing a lot of positive signs in this direction so I’m taking some heart that there are good things on the nearish horizon. Certainly, today’s meeting met my suggestions, which I don’t think were as novel as I had hoped they would be, with nobody’s skull popping out of their mouth. I take that as a positive sign.

The Fisher King: Achievement as Journey, rather than Objective

Posted: July 11, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, learning, principles of design, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches 1 Comment(There are spoilers for the 1991 movie “The Fisher King” contained within, so proceed forewarned.)

It is sometimes hard for students to understand why undertaking a particular piece of work, in a certain way and at a certain time, is so important to us. For us, as educators, knowledge is developed and constructed through awareness, practice, understanding and application, as well as the further aspects of higher-level intellectual development. When we teach something, doing the assigned homework or assignment is an important reinforcing step. We can regard these assignments in two ways: formative (where we provide feedback and use it to guide improvement) and summative (where we measure the degree to which the students have achieved the standard required, compared to some benchmarks that are important to the course). Summative activities tend to be at the end of instructional units and formative tend to be throughout, for the obvious reasons, but, more pertinently to the discussion at hand, summative activities are often seen as “high-stakes”, where formative are seen as “low”.

The problem with a high-stakes activity is that we can inadvertently encourage behaviour, such as copying, plagiarism or cheating, because students feel so much pressure to achieve and they don’t feel that there is sufficient possibility of redemption in the face of not achieving the required standard. (And, yes, from a previous post, some people start out with the intention to cheat but I shall ignore them for all of the reasons that I have previously stated.)

Ultimately, all of our assignments contribute to the development of knowledge – or they should. The formative ones, as we know, should be placed to encourage the exchange of views between student and teacher, allowing us to guide and shape in an ongoing way, where the summative ones allow us to draw a line and say “Knowledge attained, now we can move on.” Realistically, however, despite the presence of so many summative assessments during and at the end of each course, the journey through University is just that – a journey – and I sometimes present it in this light to those students who have difficulty understanding the “why” of the assignments. I try never to resort to “because I say so”, as this really exchanges no knowledge, but I’m too honest to tell that I’m not at least tempted to say this sometimes!

One of my favourite movies is the 1991 Terry Gilliam film “The Fisher King“, with Robin Williams, Jeff Bridges, Mercedes Ruehl and Amanda Plummer. This is loosely based on legend of The Fisher King, from the often contradictory and complicated stories that have arisen around the Holy Grail over the last few hundred years, and I don’t have the time to go into detail on that one here! But the core is quite simple. One man, through a thoughtless and cruel act, causes a chain of events that leads to the almost total destruction of another’s world. Meeting each other, when both are sorely wounded by their troubles, they embark upon a journey that offers redemption to the first and healing to the second. (This is perhaps the most vague way to tell a fantastic story. I strongly recommend this movie!)

The final aspect of the movie is Jack’s quest to retrieve a simple cup that Parry has identified as the Holy Grail, and that Parry has been seeking since his descent into madness. After a beating that leaves Parry comatose in hospital, Jack dons Parry’s anachronistic garb and breaks into the house of a famous architect to retrieve the simple cup. When there, he also manages to save the architect’s life, redeeming himself through both his desire to challenge his own boundaries to seek the cup for Parry and by counter-balancing his previous cruelty with an act of life-saving kindness. The cup is, of course, still a cup but it is the journey that has brought Jack back to humanity and, as he hands the simple cup to Parry who lies unseeing in a hospital bed, it is the journey that transforms the cup into the grail for long enough that Parry wakes up.

We are all on a journey, one that we set out on when we were born and one that will finish when we breathe our last, but I think our reactions to the high-stakes events in our lives are so often a reflection of those who taught us, seen through the lens of our own personality. That’s why I like to talk to students about the requirements for the constant challenges, the quests, the moments that are high-stakes, in the context of their wider journey – in the quest for knowledge, rather than the meeting of requirements for a degree.

Are you just after the piece of paper for your degree? Need the credits? Then cheating is, in some ways of thinking, a completely valid option if you can rationalise it.

Are you on a journey to develop knowledge? Need to understand everything? Then cheating is no longer an option.

Knowledge is transforming. There is no doubt about this. We learn something new and it changes the world, or us, or both! When we learn something well enough, we can create new knowledge or share our knowledge with new people. There is no doubt that the journey transforms the mundane around us into something magical, occasionally something mystical, but it is important to see it as a journey that will help us to build our achievements, rather than a set of objectives that we tick off to achieve something that is used as a placeholder for the achievement.

As I always say to my students, “If you have the knowledge, then you’re really likely to pass the course and do well. If you just try and study for the exam, then you’re not guaranteed to have the knowledge.” Formative or summative, if you regard everything we’re doing as steps to increase your knowledge, and we construct our teaching in order to do that, the low stakes and the high stakes have similar benefit, even if one isn’t so much constructed for direct feedback. If we also make sure that we are not dismissive in our systems and can even offer redemption in cases of genuine need, then our high stakes become less frightening and there is no Red Knight stalking our moments of peace and happiness, forcing us into dark and isolated pathways.

HERDSA 2012: President’s address at the closing

Posted: July 7, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, herdsa, higher education, identity, leadership, learning, measurement, reflection, thinking, university of western australia, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentThe President of HERDSA, Winthrop Professor Shelda Debowski, spoke to all of us after the final general session at the end of the conference. (As an aside, a Winthrop Professor, at the University of Western Australia, is equivalent to a full Professor (Level E) across the rest of Australia. You can read about it here on page 16 if you’re interested. For those outside Australia, the rest of the paper explains how our system of titles fits into the global usage schemes.) Anyway, back to W/Prof Debowski’s talk!

Last year, one of the big upheavals facing the community was a change at Government level from the Australian Learning and Teaching Council to the Office of Learning and Teaching, with associated changes in staffing and, from what I’m told, that rippled through the entire conference. This year, W/Prof Debowski started by referring to the change that the academic world faces every day – the casualisation of academics, disinterest in development, the highly competitive world in which we know work where waiting for the cream to rise would be easier if someone wasn’t shaking the container vigorously the whole time (my analogy). The word is changing, she said, but she asked us “is it changing for the better?”

“What is the custodial role of Higher Education?”

We have an increasing focus on performance and assigned criteria, if you don’t match these criteria then you’re in trouble and, as I’ve mentioned before, research focus usually towers over teaching prowess. There is not much evidence of a nuanced approach. The President asked us what we were doing to support people as they move towards being better academics? We are more and more frenetic regarding joining the dots in our career, but that gives us less time for reflection, learning, creativity, collegiality and connectivity. And we need all of these to be effective.

We’re, in her words, so busy trying to stay alive that we’ve lost sight of being academics with a strong sense of purpose, mission and a vision for the future. We need support – more fertile spaces and creative communities. We need recognition and acknowledgement.

One of the largest emerging foci, which has obviously resonated with me a great deal, is the question of academic identity. Who am I? What am I? Why am I doing this? What is my purpose? What is the function of Higher Education and what is my purpose within that environment? It’s hard to see the long term perspective here so it’s understandable that so many people think along the short term rails. But we need a narrative that encapsulates the mission and the purpose to which we are aspiring.

This requires a strategic approach – and most academics don’t understand the real rules of the game, by choice sometimes, and this prevents them from being strategic. You don’t stay in the right Higher Ed focus unless you are aware of what’s going on, what the news sources are, who you need to be listening to and, sometimes, what the basic questions are. Being ignorant of the Bradley Review of Australian Higher Education won’t be an impenetrable shield against the outcomes of people reacting to this report or government changes in the face of the report. You don’t have to be overly politicised but it’s naïve to think that you don’t have to understand your context. You need to have a sense of your place and the functions of your society. This is a fundamental understanding of cause and effect, being able to weigh up the possible consequences of your actions.

The President then referred to the Intelligent Careers work of Arthur et al (1995) and Jones and DeFilippi (1996) in taking the correct decisions for a better career. You need to know: why, how, who, what, where and when. You need to know when to go for grants as the best use of your time, which is not before you have all of the right publications and support, rather than blindly following a directive that “Everyone without 2 ARC DPs must submit a new grant every year to get the practice.”

(On a personal note, I submitted an ARC Discovery Project Application far too early and the feedback was so unpleasantly hostile, even unprofessionally so, that I nearly quit 18 months after my PhD to go and do something else. This point resonated with me quite deeply.)

W/Prof Debowski emphasised the importance of mentorship and encouraged us all to put more effort into mentoring or seeking mentorship. Mentorship was “a mirror to see yourself as others see you, a microscope to allow you to look at small details, a telescope/horoscope to let you look ahead to see the lay of the land in the future”. If you were a more senior person, that on finding someone languishing, you should be moving to mentor them. (Aside: I am very much in the ‘ready to be mentored’ category rather than the ‘ready to mentor’ so I just nodded at more senior looking people.)

It is difficult to understate the importance of collaboration and connections. Lots of people aren’t ready or confident and this is an international problem, not just an Australian one. Networking looks threatening and hard, people may need sponsorship to get in and build more sophisticated skills. Engagement is a way to link research and teaching with community, as well as your colleagues. There are also accompanying institutional responsibilities here, with the scope for a lot of social engineering at the institutional level. This requires the institutions to ensure that their focuses will allow people to thrive: if they’re fixated on research, learning and teaching specialists will look bad. We need a consistent, fair, strategic and forward-looking framework for recognising excellence. W/Prof Debowski, who is from University of Western Australia, noted that “collegiality” had been added to performance reviews at her institution – so your research and educational excellence was weighed against your ability to work with others. However, we do it, there’s not much argument that we need to change culture and leadership and that all of us, our leaders included, are feeling the pinch.

The President argued that Academic Practice is at the core of a network that is built out of Scholarship, Research, Leadership and Measures of Learning and Teaching, but we also need leaders of University development to understand how we build things and can support development, as well as an Holistic Environment for Learning and Teaching.

The President finished with a discussion of HERDSA’s roles: Fellowships, branches, the conferences, the journal, the news, a weekly mailing list, occasional guides and publications, new scholar support and OLT funded projects. Of course, this all ties back to community, the theme of the conference, but from my previous posts, the issue of identity is looming large for everyone in learning and teaching at the tertiary level.

Who are we? Why do we do what we do? What is our environment?

It was a good way to make us think about the challenges that we faced as we left the space where everyone was committed to thinking about L&T and making change where possible, going back to the world where support was not as guaranteed, colleagues would not necessarily be as open or as ready for change, and even starting a discussion that didn’t use the shibboleths of the research-focused community could result in low levels of attention and, ultimately, no action.

The President’s talk made us think about the challenges but, also, by focusing on strategy and mentorship, making us realise that we could plan for better, build for the future and that we were very much not alone.

HERDSA 2012: Final general talk – that tricky relationship, University/School

Posted: July 6, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, blogging, community, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, herdsa, higher education, identity, in the student's head, learning, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentWhen working in Higher Education, you fairly quickly discover that there is not actually a genuine continuum between the school level and the University level. School curricula are set, with some input from the higher ed sector, mostly by school and government, but they have little-to-no voice at the Higher Education level. We listen to our peers across the water and around our country, adopting ACM and IEEE curricula suggestions, but while we have an awareness of what the different sectors are doing (in terms of local school and University) it’s certainly not a strong, bi-directional relationship.

That’s where the Australian government reforms of 2009, designed to greatly improve participation in University, get interesting. We’ve been told to increase participation from lower SES groups who hadn’t previously considered Higher Education. We, that is ‘we the university’, have been told this. Ok. Great. Now some people will (flippantly) start ranting about how we’ll have to drop quality standards to do this – an argument that I feel is both incorrect and somewhat unpleasant in its tone. Given that we haven’t gone out of our way to try and form a continuum before, well some people have but with limited success, we can certainly address some of the problem by identifying higher education as a destination to students who may not have been aware that it was even an option for them.

This is where the work of Dr Karma Pearce comes in, won “Building community, educational attainment and university aspirations through University-School mentoring partnerships”. Dr Pearce’s research was based on developing student aspirations from traditionally disadvantaged regions in South Australia. The aim was to look at the benefits of a University/High School mentoring program conducted in a University setting, targeting final year secondary school students from the low SES schools in the area.

We are all aware of the problems that disadvantaged schools face and the vicious circularity of some of these problems. Take Chemistry. To teach chemistry properly, you need teachers and lab resources, including consumables. It’s not like a computer lab that can be run on oldish equipment in a room somewhere – chemistry labs have big technical and safety requirements, and old chemicals either don’t work or get consumed in reactions. If your lab is bad, your numbers drop because the teaching suffers. If the numbers drop below a certain level for schools in South Australia – the class gets cancelled. Now you have a Chem teacher and no students. Therefore, repurposed teacher or, shortly, no teacher. (Of course, this assumes that you can even get a chemistry teacher.)

The University of South Australia had recently build new chemistry labs in another campus, leaving their old labs (which are relatively near to several traditionally disadvantaged areas) free. To the researcher’s and University’s credit (I’m serious, kudos!) they realised that they could use these labs to support 29 secondary school students from schools that had no chem labs. The school students participated in weekly lecture, tutorial and practical chemistry classes at Mawson Lakes campus, with the remaining theory conducted in their own schools. There were two High School teachers based in two of the schools, with a practical demonstrator based at Mawson Lakes. To add the mentoring aspect, four final year undergraduate students were chosen to be group mentors. The mentors required a minimum of credit (B) level studies for three chemistry courses. The mentor breakdown, not deliberately selected, was three women and one man, with two from private (fee-paying) schools and two from regional state schools. Mentors had transport provided, a polo shirt with logo, were paid for their time and received a significant amount of mentor training as well as a weekly meeting with a University coordinator.

The mentors assisted throughout the 26 week program and, apart from helping with chemistry, shared their experiences of University as they worked with the students. Of the 20 secondary students who completed the program (10 F, 10 M), they indicated in surveys that they thought they now understand what Uni life was going to be like but, more importantly to me, that they thought it was achievable for them. From that group, 35% of them had family who had been to University, but all of the secondary participants who made it to the end of the program had enrolled to go to Uni by the end of their Year 12 studies.

In discussion, a couple of points did emerge, especially regarding the very high teacher/student ratio, but overall the message from the research is pretty positive. Without having to change anything at the actual University level, a group of students, who didn’t come from a “university positive” environment and who were at some of the most disadvantaged schools in the state, now thought that University was somewhere that they could go – their aspirations now included University. What a fantastic result!

One side note, at the end, that I found a little depressing was that some students had opted to go to another University, not UniSA, and at least one gave the reason that they had been lured there by the free iPad that was being issued if you enrolled in a Bachelor of Science. Now, in the spirit of full honesty, that’s my University that they’re talking about and I know enough about the amazing work done by Bob Hill, Simon Pyke and Mike Seyfang (as well as a cast of hundreds) to completely rebuild the course to a new consistent standard, with a focus on electronic (and free) textbooks, to know that the iPad is the icing on the cake (so to speak). But, to a student from a disadvantaged school, one where a student going into medicine (and being the first one in the 50 year history of the school) is Page 3 news in the main state newspaper, an iPad is a part of a completely different world. If this student is away at a camp with students from more privileged background, this device is not about electronic delivery or lightening the text book burden or interactive science displays and instant communication – it’s about fitting in.

I found this overall talk very interesting, because it gave an excellent example of how we can lead educationally by sharing our resources while sharing the difficulties of the high school/University transition, but it also made me think about how students see the things that we do to improve their education. Where I see a lab full of new computers, do students see a sign of stability and affluence that convinces them that we’ll look after them or do they see “ho hum” because they’re only 21″ screens and not the i7 processor?

Once again, when I look at things from my view, what do my students see?

HERDSA 2012: Connecting with VET

Posted: July 6, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: blogging, community, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, Generation Why, herdsa, higher education, learning, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentAs part of the final session I attended in the general conference, I attended a talk by A/Prof Anne Langworthy and Dr Susan Johns who co-presented a talk on “Why is it important for Higher Education to connect with the VET sector?” As a point of clarification, VET stands for Vocational Education and Training, as I’ve previously mentioned, and is generally concerned with trade qualifications, with some students going on to diplomas and advanced diplomas that may be recognised as some or all of a first-year University course equivalent. If a student starts in a trade and then goes to a certain point, we can then easily accept them into an articulation program.

The Tasmanian context, a small state that is still relatively highly ruralised, provides a challenging backdrop to this work, as less than 18% of school leavers who could go on to University actually do go on to University. Combine this with the highest lower socio-economic status (SES) population by percentage in Australia, and many Tasmanians can be considered to be disadvantaged by both access to and participation in University level studies. Family influence plays a strong part here – many families have no-one in their immediate view who has been to University at all, although VET is slightly more visible.

Among the sobering statistics presented, where that out of a 12 year schooling system, where Year 12 is the most usual pre-requisite to University entry, as a state, the percentage of people 15 years or older who had year 10 schooling or less was 54%. Over half the adult population had not completed secondary schooling, the usual stepping stone to higher education.

The core drivers for this research were the following:

- VET pathways are more visible and accessible to low SES/rural students because the entry requirements aren’t necessarily as high and someone in their family might be able to extol the benefits.

- There are very low levels of people articulating from VET to Higher Ed – so, few people are going on to the diploma.

- There is an overall decline in VET and HE participation.

- Even where skills shortages are identified, students aren’t studying in the areas of regional need.

- UTAS is partnering with the Tasmanian VET provider Tasmanian Polytechnic and Skills Institute.

An interesting component of this background data is that, while completion rates are dropping for the VET skills, individual module completion rates are still higher than the courses in which the modules sit. In other words, people are likely to finish a module that is of use to them, or an employer, but don’t necessarily see the need of completing the whole course. However, across the board, the real problem is that VET, so often a pathway to higher ed for people who didn’t quite finish skill, is dropping in percentage terms as a pathway to Uni. There has been a steady decline in VET to HE articulation in Tasmania across the last 6 years.

The researchers opted for an evidence based approach to examine those students who had succeeded in articulating from VET to HE, investigating their perceptions and then mapping existing pathways to discover what could be learned. The profile of VET and HE students from the SES/rural areas in Tas are pretty similar although the VET students who did articulate into Uni were less likely to seek pathways that rewarded them with specific credits and were more likely to seek general admission. Given that these targeted articulations, with credit transfer, are supposed to reflect student desire and reward it, or encourage participation in a specific discipline, it appears that these pathways aren’t working as well as they could.

So what are the motivators for those students who do go from VET to Uni? Career and vocational aspirations, increased confidence from doing VET, building on their practical VET basis, the quality and enthusiasm of their VET teachers, the need to bridge over an existing educational hurdle and satisfaction with their progress to date. While participation in VET generally increased a student’s positive attitude to study, the decision to (or not to) articulate often came down to money, time, perceived lack of industry connection and even more transitional assistance.

It’s quite obvious that our students, and industry, can become fixated with the notion of industrial utility – job readiness – and this may be to the detriment to Universities if we are perceived as ivory towers. More Higher Ed participation is excellent for breaking the poverty cycle, developing social inclusion and the VET to Higher Ed nexus offers great benefits in terms of good student outcomes, such as progression and retention, but it’s obvious that people coming from a practice-based area, especially in terms of competency training, are going to need bridging and some understanding to adapt to the University teaching model. Or, of course, our model has to change. (Don’t think I was going to sneak that one past you.)

The authors concluded that bridging was essential. articulation and credit transfer arrangement should be reviewed and that better articulation agreements should be offered in areas of national and regional priority. The cost of going to University, which may appear very small to students who are happy to defer payment, can be an impediment to lower SES participants because, on average, people in these groups can be highly debt averse. The relocation costs and support costs of moving away from a rural community to an urban centre for education is also significant. It’s easy sometimes to forget about how much it costs to live in a city, especially when you deprive someone of their traditional support models.

Of course, that connection to industry is one where students can feel closer when they undertake VET and Universities can earn some disrespect, fairly or not, for being seen to be ivory towers, too far away from industry. If you have no-one in your family who has been to Uni, there’s no advocate for the utility of ‘wasting’ three years of your life not earning money in order to get a better job or future. However, this is yet another driver for good industry partnerships and meaningful relationships between industry, VET and Higher Education.

It’s great to see so much work being down in both understanding and then acting to fix some of the more persistent problems with those people who may never even see a University, unless we’re dynamic and thoughtful in our outreach programs. On a personal note, while Tasmania has the lowest VET to HE conversion, I noticed that South Australia (my home state) has the second lowest and a similar decline. Time, I think, to take some of the lessons learned and apply them in our back yard!

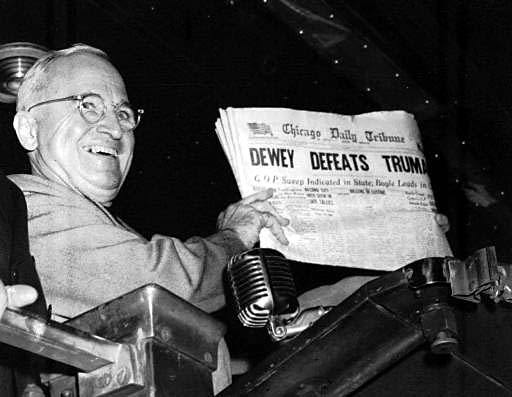

Dewey Defeats Truman – again!

Posted: June 30, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: dewey defeats truman, education, higher education, internet is forever, learning, measurement, new media, reflection, teaching approaches, the internet is forever, thinking Leave a commentThe US Presidential race in 1948 was apparently decided when the Chicago Tribune decided to publish their now infamous headline “Dewey Defeats Truman” (Wikipedia link). As it happened, Truman had defeated Dewey in an upset victory. The rather embarrassing mistake was a combination of an early press deadline, early polls and depending upon someone who had been reliable in their predictions previously. What was worse was that the early editions had predicted a significant reversed result, with a sweeping victory for Dewey. Even as other results came in indicating that this wasn’t so, the paper stuck to the headline, while watering down the story.

Ultimately, roughly 150,000 papers were printed that were, effectively, utter and total nonsense.

Because he’s a President, I doubt that Truman actually used the phrase “neener, neener”. (Associated Press, photo by Byron Rollins, via Wikipedia)

This is a famous story in media reporting and, in many ways, it gives us a pretty simple lesson: Don’t Run The Story Until You Have the Facts. Which brings me to the reporting on the US Supreme Court regarding the constitutionality of the controversial health care bill.

Students have to understand how knowledge is constructed, if they are to assist in their own development, and the construction of what is accepted to be fact is strongly influenced by the media, both traditional and new. We’ve moved to a highly dynamic form of media that can have a direct influence on events as they unfold. Forty years ago, you’d read about an earthquake that killed hundreds. Today, dynamic reporting of earthquakes on social media save lives because people can actually get out of the way or get help to people faster.

I’m a great fan of watching new media reporting, because the way that it is reported is so fluid and dynamic. An earthquake happens somewhere and the twitter reporting of it shows up as a corresponding twitter quake. People then react and spread the news, editing starts to happen and, boom, you have an emergent news feed built by hundreds of thousands of people. However, traditional media, which has a higher level of information access and paid staff to support, does not necessarily work the same way. Trad media builds stories on facts, produces them, has time to edit, commits them to press or air and has a well-paid set of information providers and presenters to make it all happen. (Yes, I know there are degrees in here and there are ‘Indy’ trad media groups, but I think you get my point.)

It was very interesting, therefore, to see a number of trad news sources get the decision on the health care bill completely and utterly wrong. When the court’s decision was being read out, an event that I watched through many eyes as I was monitoring feed and reaction to feed, CNN threw up a headline, before the decision had been announced saying that the bill had been defeated.

And FOX news reported the same thing.

Only one problem. It wasn’t true.

As this fact became apparent, first of all, the main stories changed, then the feeds published from the main stories changed and then, because nobody had printed a paper yet, some of the more egregious errors disappeared from web sites and feeds – never to be seen again.

Oh wait, the Internet is Forever, so those ‘disappeared’ feeds had already been copied, pictured and cached.

Now, because of the way that the presenting Justice was actually speaking, you could be forgiven for thinking that he was about to say that the bill had been defeated. Except for the fact that there were no actual print deadlines in play here – what tripped up CNN and FOX appears to have been their desire to report a certain type of story first. In the case of FOX, had the bill been defeated, it’s not hard to imagine them actually ringing up President Obama to say “neener, neener”. (FOX news is not the President, so is not held to the same standards of decorum.)

The final comment on this story, and which should tell you volumes about traditional news gathering mechanisms in the 21st century, is that there was an error in a twitter/blog feed reporting on the decision which made an erroneous claim about the tax liability of citizens who wished to opt out of the program. So, just to be clear, we’re talking about a non-fact-checked social media side feed and there’s a mistake in it. Which then a very large number of traditional news sources presented as fact, because it appears that a large amount of their expensive resource gathering and fact checking amounts to “Get Brad and Janet to check out what’s happening on Twitter”. They they all had to fix and edit (AGAIN) once they discovered that they had effectively reported an error made by someone sitting in the room, typing onto a social media feed, as if it had gone through any kind of informational hygiene process.

Here are my final thoughts. As an experiment, for about a week, read Fark, Metafilter and The Register. Then see how many days it is before the same stories show up on your television, radio and print news. See how much change the stories have gone through, if any. Then look for stories that go the other way around. You may find it interesting when you work out which sources you trust as authorities, especially those that appear more trustworthy because they are traditional.

(Note: Apologies for the delay in posting. As part of my new work routine, I rearranged some time and I realised that posting 6 hours late wouldn’t hurt anyone.)