What Do You Mean… “Like”?

Posted: November 16, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: blogging, education, feedback, games, higher education, teaching approaches, thinking, tools 8 CommentsI was alerted to a strange game the other day. Go to Mitt Romney’s Facebook page, note the number of ‘likes’ and then come back later to see if the number had gone up or down. As it turns out, the number of Facebookers who ‘like’ the former Presidential Candidate’s Facebook page is dropping at a noticeable but steady rate. My estimates are, if this drop is maintained and it is linear, it will be about 1666 days until there are zero people liking the page. (Estimates vary, but the current rate of loss is somewhere around 11 likes a minute. You can watch it here in real time.) I mention this not to add to Mr Romney’s woes, because he is already understandably not happy that he lost the election, although you may disagree with the reasoning in the linked article. I mention this because it identifies how nebulous our association is with the term and the concept of ‘like’.

For those who have recently returned from 7 years of bonding with a volleyball in the Pacific, Facebook does not allow you to ‘dislike’ things, it only allows you to comment or hit the ‘like’ button (or hide the comment or post but that’s a separate thought). What does it mean then to not click the ‘like’ button or to comment? Thank you, Facebook, for presenting us with yet another false dichotomy and for giving us such a large example on Mr Romney’s page. Before the election, millions of people liked Mr Romney’s page which, one can only imaging, meant that they were showing him support and saying “Go, Mitt!” Now that, in a completely different way, the message “Go, Mitt” has been communicated, it appears that, at a time when an unsuccessful candidate would need the most support, the followers are leaving. Now, this is important because, as I understand it, to stop liking something you have to take the active step of clicking on something – it doesn’t just expire in a short timeframe. People are actively choosing to remove their liking of Mr Romney’s page.

Why?

Well, there’s a lot of speculation about this, including the notion that some of the initial surge of followers came from buying friends by bringing in other accounts that are used by non-people but this still doesn’t explain where the unlikes are coming from because, after all, a Justin Bieber Slashfic Spambot is nothing if not loyal in its mechanically allocated trust. What is probably happening here is that the social media front ends were being used explicitly as part of a campaign to see Mr Romney elected President and, understandably, the accounts are now seeing much less use and, fickle as the real Internet is, you’re only as good as your last post or as hot as your posting frequency. The staffer or group of staffers that were paid to do this have now lost their jobs and the account is heading towards the account graveyard. (The saddest thing about any competition like this is that someone, somewhere, who has been doing a good job may still lose their job because the public didn’t support their candidate. I try to remember that before I overly celebrate either victory or defeat, although I don’t always succeed.)

What concerns me are the people who liked this Facebook page, legitimately and as real people, and have now turned around and deliked it, because this can easily be seen as a punitive action. It has no real impact on Mr Romney in any sense but it does make him look increasingly unpopular and, really, it achieves absolutely nothing. What does ‘like’ mean in this context? I support you until you fail me? I support you because you might be President and I have some strange mental model that your Secretary of State will be picked randomly from your Facebook followers?

To me, honestly, a lot of this looks like spite. After all, what does it hurt to remain a liker of a dead page? It doesn’t, unless your aim is to send a message. However, I think that Mr Romney probably already knows that he didn’t get elected to the highest office his country can offer – but I’m sure that when he becomes aware of all of the people fleeing his page, it will really neatly reinforce how he could have improved his campaign.

Oh, wait, that’s my point! The vocabulary of like/delike (recall that there is no dislike option) is fundamentally useless because of its confused binary nature. Does no ‘like’ mean ‘dislike’,’meh’,’sort of like’,’maybe in a dark room’ or ‘I missed this’? Does ‘like’ mean ‘yay!’, ‘hugs!’, ‘i want to smell your hair’ or ‘*gritted teeth at your good fortune*’? Or does it just mean ‘like’? We have no idea unless someone comments and, given that we have the easy out of ‘like’, many people won’t comment because they have the deceptively communicative nature of the flawed channel of ‘like’!

Like most Universities, we have a survey that we run on students at the end of courses to find out how they felt about the course, what their experience was. Regrettably, a lot of the time, what you end up measuring was how much a student liked you. It’s on a 7 point Likert scale but, and many students don’t realise this, the middle point is not ‘non-committed to like/dislike’, it counts as ‘not like’. Hence if you get 7/7 from everyone for something and get one 4/7, you no longer have 100% broad agreement regarding that point. Because there is confusion about what this means (and there is a not applicable that is separate to the scale), students who don’t care about anything tend to write down the middle and end up counting as a vote against. Is this fair? Well, is that the question? Let me ask a different one – was it what the student intended? Maybe/maybe not. As it stands, the numbers themselves are not very much use as they tell you what people feel but not what they’re thinking. The comments that also come on the same form are far more informative than the numbers. Much as with Facebook, there is confusion over like/dislike, but the comments are always far more useful in making improvements and finding out what people really think.

I feel (to my own surprise) some empathy for Mr Romney at the moment because there are hundreds, if not thousands, of people a day sending him a message that is utterly and totally confusing, as well as being fundamentally hypocritical. Ok, yes, he might not care to know what every American thought he got wrong, the Internet can be challenging that way, but ‘deliking’ him is not actually achieving anything except covering your tracks.

What did any of these people, who have now left, actually mean by ‘like’?

Being a Hypnoweasel and Why That’s a Bad Idea.

Posted: November 7, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, collaboration, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, games, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, research, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, universal principles of design 2 CommentsI greatly enjoy the television shows and, as it turns out, the writing of Derren Brown. Mr Brown is a successful conjurer, hypnotist and showman who performs stage magic and a range of deceits and experiments, including trying to turn a random member of the public into an assassin or convincing people that they committed a murder.

His combination of trickery, showmanship, claimed psychology/neurolinguistic programming and hypnotism makes for an interesting show – he has been guilty of over claiming in earlier shows and, these days, focusses on the art of misdirection, with a healthy dose of human influence to tell interesting stories. I am reading his book “Tricks of the Mind” at the moment and the simple tricks he discusses are well informed by the anecdotes that accompany them. However, some of his Experiments and discussions of the human aspects of wilful ignorance of probability and statistics are very interesting indeed and I use these as part of my teaching.

In “The System”, Derren shares his “100% successful horse race prediction system” with a member of the public. He also shows how, by force of will alone, he can flip a coin 10 times and have it come up heads – with no camera trickery. I first saw this on a rather dull plane flight and watched with interest as he did a number of things that, characteristically, showed you exactly what he was doing but cleverly indicated that he was doing something else – or let you believe that he was doing something else. “The System” is a great thing to show students because they have to consider what is and what isn’t possible at each stage and then decide how he did it, or how he could have done it. By combining his own skill at sleight of hand, his rather detailed knowledge of how people work and his excellent preparation, “The System” will leave a number of people wondering about the detail, like all good magic should.

The real reason that I am reading Derren at the moment, as well as watching him carefully, is that I am well aware how easy it is to influence people and, in teaching, I would rather not be using influence and stagecraft to manipulate my students’ memories of a teaching experience, even if I’m doing it unconsciously. Derren is, like all good magicians, very, very good at forcing cards onto people or creating situations where they think that they have carried out an act of their own free will, when really it is nothing of the kind. Derren’s production and writings on creating false memory, where a combination of preparation, language and technique leads to outcomes where participants will swear blind that a certain event occurred when it most certainly did not. This is the flashy cousin of the respectable work on cognition and load thresholds, monkey business illusion anyone?, but I find it a great way to step back critically and ask myself if I have been using any of these techniques in the showman-like manipulation of my students to make them think that knowledge has been transferred when, really, what they have is the memory of a good lecture experience?

This may seem both overly self-critical and not overly humble but I am quite a good showman and I am aware that my presentation can sometimes overcome the content. There is, after all, a great deal of difference between genuinely being able to manipulate time and space to move cards in a deck, and merely giving the illusion that one can. One of these is a miracle and the other is practise. Looking through the good work on cognitive load and transfer between memory systems, I can shape my learning and teaching design so that the content is covered thoroughly, linked properly and staged well. Reading and watching Derren, however, reminds me how much I could undo all of the good work by not thinking about how easy it is for humans to accept a strange personally skewed perspective of what has really happened. I could convince my students that they are learning, when in reality they are confused and need more clarification. The good news is that, looking back, I’m pretty sure that I do prepare and construct in a way that I can build upon something good, which is what I want to do, rather than provide an empty but convincing facade over the top of something that is not all that solid. Watching Derren, however, lets me think about the core difference between an enjoyable and valuable learning experience and misdirection.

There are many ways to fool people and these make for good television but I want my students to be the kind of people who see through such enjoyable games and can quickly apply their properly developed knowledge and understanding of how things really work to determine what is actually happening. There’s an old saying “Set a thief to catch a thief” and, in this case, it takes a convincing showman/hypnotist to clarify the pitfalls possible when you get a little too convincing in your delivery.

Deception is not the basis for good learning and teaching, no matter how noble an educator’s intent.

Gamification: What Happens If All Of The Artefacts Already Exist

Posted: September 4, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, educational problem, feedback, games, higher education, in the student's head, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches, tools Leave a commentI was reading an article today in May/June’s “Information Age”, the magazine of the Australian Computer Society, entitled “Gamification Goes Mainstream”. The article identified the gaming mechanics that could be added to businesses to improve engagement and work quality/productivity by employees. These measures are:

- Points: Users get points for achievements and can spend the points on prizes.

- Levelling: Points get harder to get as the user masters the systems.

- Badges: Badges are awarded and become part of the user’s “trophy page”, accompanying any comments made by the user.

- Leader Boards: Users are ranked by points or achievement.

- Community: Collaborative tools, contests, sharing and forums.

Now, of course, there’s a reason that things exist like in games and that’s because most games are outside of the physical world and, in the absence of the natural laws that normally make things happen and ground us, we rely upon these mechanics to help us to assess our progress through the game and provide us with some reward for our efforts. Now, while I’m a great believer in using whatever is necessary to make work engaging and to make like more enjoyable, I do wonder about the risk of setting up parallel systems that get people to focus on things other than their actual work.

Yes, yes, we all know I have issues with extrinsic motivations but let’s look again at the list of measures above, which would normally be provided in a game to allow us to make sense of the artificial world in which we find ourselves, and think about how they apply already in a workplace.

- Points that can be used to purchase things: I think that we call this money. If I provide a points system for buying company things then I’ve created a second economy that is not actually money.

- Levelling: Oh, wait, now it’s hard to spend the special points that I’ve been given so I’ve not only created a second economy, I’ve started down the road towards hyperinflation by devaluing the currency. (Ok, so the promotional system works here in my industry like that – our ranks are our levels, which isn’t that uncommon.)

- Badges: Plaques for special achievement, awards, post-nominal letters, Fellowships – anything that goes on the business card is effectively a badge.

- Leader Boards: Ok, this is something that we don’t often see in the professional world but, let’s face it, if you’re not on top then you’re not the best. Is that actually motivational or soul-destroying? Of course, if we don’t have it yet, then you do have to wonder why, given every other management trend seems to get a workout occasionally. I should note that I have seen leader boards at my workplace which have been ‘anonymised’ but given that I can see myself I can see where I sit – now not only do I know if am not top, I don’t know who to ask about how to get better, which has been touted as one of the reasons to identify the stars in the first place.

- Community: We do have collaborative tools but they are focussed on helping us achieve our jobs, not on achieving orthogonal goals associated with a gaming system. We also have comment forums, discussion mechanisms such as mailing lists and the like. Contests? No. We don’t have contests. Do we? Oh wait, national competitive grant schemes, local teaching schemes, competitive bidding for opportunities.

Now if people aren’t engaging with the tasks that are expected of them (let’s assume reasonably) then, yes, we should find ways to make things more interesting to encourage participation. However, talking about all of the game mechanics above, it’s obviously going to take more thought than just picking a list of things that we are already doing and providing an alternative system that somehow makes everything really interesting again.

I should note that the article does sound a cautionary tone, from one of the participants, who basically says that it’s too soon to see how effective these schemes are and, of course, Kohn is already waggling a finger at setting up a prize/compliance expectation. So perhaps the lesson here is “how can we take what we already have and work out how to make it more interesting” rather than taking the lessons in required constructions of phenomena from a completely artificial environment where we have to define gravity in order to make things fall. Gamification shows promise in certain direction, mainly because there’s a lot of fun implicit in the whole process, but the approaches need to be carefully designed to make sure that we don’t accidentally reinvent the same old wheel.

In A Student’s Head – Mine From 26 Years Ago

Posted: August 11, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, ALTA, blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, games, higher education, in the student's head, principles of design, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentI attended an Australian Council of Deans of ICT Learning and Teaching Academy event run by Elena Sitnikova from the University of South Australia. Elena is one of the (my fellow?) Fellows in ALTA and works in Cyber Security and Forensic Computing. Today’s focus was on discussing the issues in ICT education in Australia, based on the many surveys that have been run, presenting some early work on learning and teaching grants and providing workshops on “Improving learning and teaching practice in ICT Education” and “Developing Teamwork that Works!”. The day was great (with lots of familiar faces presenting a range of interesting topics) and the first workshop was run by Sue Wright, graduate school in Education, University of Melbourne. This, as always, was a highly rewarding event because Sue forced me to go back and think about myself as a student.

This is a very powerful technique and I’m going to outline it here, for those who haven’t done it for a while. Drawing on Bordieu’s ideas on social and cultural capital, Sue asked us to list our non-financial social assets and disadvantages when we first came to University. This included things like:

- Access to resources

- Physical appearance

- Educational background

- Life experiences

- Intellect and orientation to study

- Group membership

- Accent

- Anything else!

When you think about yourself in this way, you suddenly have to think about not only what you had, but what you didn’t have. What helped you stay in class?What meant that you didn’t show up? From a personal perspective, I had good friends and a great tan but I had very little life experience, a very poor study ethic, no real sense of consequences and a very poor support network in an academic sense. It really brought home how lucky I was to have a group of friends that kept me coming to University. Of course, in those pre-on-line days, you had to come to Uni to see your friends, so that was a good reason to keep people on campus – it allowed for you to learn things by bumping into a people, which I like to refer to as “Brownian Communication”.

This exercise made me think about my transition to being a successful student. In my case, it took more than one degree and a great deal more life experience before I was ready to come back and actually succeed. To be honest, if you looked at my base degree, you’d never have thought that I would make it all the way to a PhD and, yet, here I am, on a path where I am making a solid and positive difference.

Sue then reminded people of Hofstede’s work on cultural dimensions – power distance, individualism versus collectivism, and uncertainty avoidance. How do students work – do they need a large ‘respect gap’ between student and teacher? Do they put family before their own study? Do they do anything rather than explore the uncertain? It’s always worth remembering that, where “the other” exists for us, we exist as “the other” reciprocally. While it’s comfortable as white, culturally English and English speaking people to assume that “the other” is transgressing with respect to our ‘dominant’ culture, we may be asking people to do something that is incredibly uncomfortable and goes far beyond learning another language.

One of the workshop participants was born and grew up in Korea and he made the observation that, when he was growing up, the teacher was held at the same level of the King and your father – and you don’t question the King or your father! He also noted that, on occasion, ‘respect’ had to be directed towards teachers that they did not actually respect. He had one bad teacher and, in that class, the students asked no questions and just let the teacher talk. As someone who works within a very small power distance relationship with y students, I have almost never felt disrespected by anything that my students do, unless they are actively trying to be rude and disrespectful. If I have nobody following, or asking questions, then I always start to wonder if I’ve been tuned out and they are listening to the music in their heads. (Or on their iPhones, as it is the 21st Century!)

Australia is a low power distance/high individualism culture with a focus on the short-term in many respects (as evidence by profit and loss quarterly focus and, to be frank, recent political developments). Bringing people from a high PD/high collectivism culture, such as some of those found in South East Asia, will need some sort of management to ensure that we don’t accidentally split the class. It’s not enough to just say “These students do X” because we know that we can, with the right approach, integrate our student body. But it does take work.

As always, working with Sue (you never just listen to Sue, she always gets you working) was a very rewarding and reflective activity. I spent 20 minutes trying to learn enough about a colleague from UniSA, Sang, that I could answer questions about his life. While I was doing this, he was trying to become Nick. What emerged from this was how amazingly similar we actually are – different Unis, different degrees, different focus, one Anglo-origin, one Korean-origin – and it took us quite a while to find things where we were really so different that we could talk about the challenges if we had to take on each other’s lives.

It was great to see most of the Fellows again but, looking around a large room that wasn’t full to the brim, it reminded me that we are often talking to those people who already believe that what we’re doing is the right thing. The people that really needed to be here were the people who weren’t in the room.

I’m still thinking about how we can continue our work to reach out and bring more people into this very, very rewarding community.

Teaching Ethics in a Difficult World: Free Range and Battery Games

Posted: August 9, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, community, education, educational problem, ethics, free range games, games, higher education, in the student's head, principles of design, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, workload 2 Comments(Note, this is not a post about the existing game company, Free Range Games, although their stuff looks cool!)

I enjoy treating ethics or, to be more precise, getting the students to realise the ethical framework that they all live within. I’ve blogged before about this and how easy it is to find examples of unethical behaviour but, as we hear more stories about certain ‘game-related’ industries and the way that they teach testers, it becomes more and more apparent that we are reaching a point where the ethical burden of a piece of software may end up becoming something that we have to consider.

We’re already aware of the use of child labour in some products and people can make a decision not to shop at certain stores or buy certain products – but this requires awareness and tying the act to the brand.

In the areas I live in, it’s very hard to find a non-free range chicken, even in a chicken take-away shop (for various definitions of ‘free range’ but we pretty much do mean ‘neither battery nor force fed’) and eggs are clearly labelled. Does this matter to you? If so, you can make an informed decision. Doesn’t matter to you? Buy the cheapest or the tastiest or whichever other metric you’re using.

But what about games? You don’t have to look far (ea_spouse and the many other accounts available) to see that the Quality Assurance roles, vital to good games, are seeing a resurgence in the type of labour management that is rapidly approaching the Upton Sinclair Asymptote. Sinclair wrote a famous turn-of-the 20th Century novelisation of the conditions in the meat packing industry, “The Jungle”, that, apart from a rather dour appeal to socialism at the end, is an amazing read. It changed conditions and workers’ rights because it made these invisible people visible. Once again, as well apparently fall in love with the ‘wealth creators’ (an Australian term that is rapidly become synonymous with ‘robber baron’) all over again, we are approaching this despite knowing what the conditions are.

What I mean by this is that it is well known that large numbers of staff in the QA area in games tolerate terrible conditions – no job security, poor working conditions, malicious and incompetent management – and for what? To bring you a game. It’s not as if they are fighting to maintain democracy (or attack democracy, depending on what you consider to be more important) or staying up for days on end trying to bring the zombie infection under control. No, the people who are being forced into sweatboxes, occasionally made to work until they wet themselves, who are unceremoniously fired at ‘celebration’ events, are working to make sure that the people who wrote your game didn’t leave any unexplained holes in the map. Or that, when you hit a troll with an axe, it inflicts damage rather than spontaneously causing the NyanCat video to play on your phone.

This discussion of ethics completely ignores the ethics of computer games that demean or objectify women, glorify violence or any of the ongoing issues. Search for ethics of video games and it is violence and sexism that dominates the results. It’s only when you start searching for “employee abuse video game” that you start to get hits. Here are some quotes from one of them.

It seems as though the developers of L. A. Noire might have been under more pressure themselves than any of the interrogated criminals in their highly praised crime drama. Reports have surfaced about employees being forced to work excruciating hours, in some cases reaching 120 hour weeks and 22 hour days. In addition, a list has been generated of some 130 members of the Australian-based Team Bondi, the creators of L. A. Noire, whose names have been omitted from the game’s own credits.

…

On the subject of the unprecedented scope of the project for Australian developers, McNamara replied, “The expectation is slightly weird here, that you can do this stuff without killing yourself; well, you can’t, whether it’s in London or New York or wherever; you’re competing against the best people in the world at what they do, and you just have to be prepared to do what you have to do to compete against those people. The expectation is slightly different.”

The saddest thing, to me, is that everyone knows this. The same people who complain on my FB feed back how overworked they are and how little they see their family then go out and buy games that have been produced in electronic sweatshops. You didn’t buy L. A. Noire? Rockstar San Diego are on the “overworking staff” list for “Red Dead Redemption” and the “not crediting everyone” for “Manhunt 2”. (That last one might not be so bad!)

Everyone talks about the crunch as if it’s unavoidable. Well, yes , it is, if you intend to work people to the crunch. We’ve seen similar argument for feedlot meat production, battery animals and, let’s not forget, that there have always been “excellent” reasons for slavery in economic and social terms.

This is one of the hardest things to talk about to my students because they’re not dumb. They read, often more widely than I do in these areas. They know that for all my discussions of time management and ethics, if they get a certain kind of job they will work 7 days a week, 10-14 hours a day, in terrible conditions and maybe, just maybe, if they sell their soul enough they can get a full-time job, rather than being laid off indiscriminately. They know that the message coming down from these companies is “maximum profit, minimum spend” and, of course, most of these game companies aren’t profitable so that’s less about being mercenary and more about survival.

But, given that these products are not exactly… essential (forgive me, Deus Ex!), one has to wonder whether terms like ‘survival’ have any place in this discussion. Is it worth nearly killing people, destroying their social lives and so one, to bring a game to market? People often say “Well, they have a choice” and, in some ways, I suppose they do – but in an economic market where any job is better than job, and people can make decisions at 15 that lead to outcomes they didn’t expect at 25, this seems both ungenerous and thoughtless.

Perhaps we need the equivalent of a ‘Free Range/Organic’ movement for games: All programmers and QA people were officially certified to have had at least 8 hours sleep a night, with a minimum break of 50 hours every 6 days and were kept at a maximum density of 2 programmers per 15 square metres, in a temperature and humidity controlled environment that meets recognised comfort standards.

(Yeah, I didn’t include management. I think they’re probably mostly looking after themselves on that one. 🙂 )

Then you can choose. If it matters to you, buy 21st century Labour Force Games – Ethically and sustainably produced. If it doesn’t matter, ignore it and game on.

Good Design: Building In Important Features From the Start

Posted: July 17, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: design, education, educational problem, feedback, games, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, principles of design, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design Leave a commentThe game “Deus Ex” is widely regarded as one of the best computer games that has been made so far. It has won a very large number of “best game” awards and regularly shows up in the top 5 of lists of “amazing games”. Deus Ex was released in 2000, designed and developed by Ion Storm under Warren Spector and Harvey Smith and distributed by Eidos. (I mentioned it before in this post, briefly.) Here is the description of this game from Wikipedia:

Set in a dystopian world during the year 2052, the central plot follows rookie United Nations Anti-Terrorist Coalition agent JC Denton, as he sets out to combat terrorist forces, which have become increasingly prevalent in a world slipping ever further into chaos. As the plot unfolds, Denton becomes entangled in a deep and ancient conspiracy, encountering organizations such as Majestic 12, the Illuminati, and the Hong Kong Triads throughout his journey.

Deus Ex had a cyberpunk theme, a world of shadowy corporations and many corruptions of the human soul, ranging from a generally materialistic culture to body implants producing cyborg entities that no longer had much humanity. While looking a lot like a First-Person Shooter (you see through the character’s eyes and kill things), the game also had a great deal of stealth play (sneaking around trying very hard not to get noticed, shot or both). However, what sets DE apart from most other games it that the choice of how you solved most of the problems was pretty much left up to you. This was no accident. The fact that you could solve 99% of the problems in the game by using different forms of violence, many forms of stealth or a combination of these was down to the way that the game was designed.

When I was at Game Masters at ACMI, Melbourne, over the weekend, I was able to read the front page of a document entitled “Just What IS Deus Ex” by Warren Spector. Now, unfortunately, they had a “no photographs” rule so I don’t have a copy of it (and, for what it’s worth, I also interpreted that to mean “no tiresome hand transcription onto the iPhone in order to make a replica” ) but one of the most obvious and important design features was that they wanted to be able to support player exploration: players’ actions had to have consequences and players needed to be able to make their plans, without feeling constrained by the world. (Fortunately, while not being the actual document, there is an article here where Warren talks about most of the important things. If you’re interested in design, have a look at it after you’ve finished this.) Because of this, a number of the items in the game can be used in a number of quite strange ways and, while it appears that this is a bug, suddenly you’ll run across an element of the game that makes you realise that the game designers knew that this was possible.

For example, in the Triad-run Hong Kong of 2052, there is a very tall tower on one edge of the explorable area. There are grenades (LAMs)in the game that adhere ‘magnetically’ to walls and then explode if armed and someone enters their proximity. However, it is possible to use these grenades to climb up walls, assuming you don’t arm them of course, by sticking them to walls, getting close enough to hop up, placing another grenade above you and then doing the same thing. With patience, you can climb quite high. Sounds like a bug, right? Yeah, well, that’s what I thought until I climbed to the top of the tower in Hong Kong and found a guy, one of the Non-Player Characters, standing on top.

This was a surprise but it shouldn’t have been. I’d already realised that there was always more than one way to do things and, because the game was designed to make it is as easy as possible for me to try many paths to achieve success, the writer had put in early hints designed to discourage a ‘blow everything up’ approach. The skill system makes it relatively easy for you to make your life a lot easier by working with what is already in the environment rather than trying to do it all yourself.

In terms of the grenades, rather than just being pictures on a wall, they became real world objects when placed and were as solid as any other element. This allowed them to be climbed and the designers/programmers recognised this by putting a guy on top of a tower that you had no other way to get to (without invoking cheats). The objects in Deus Ex were designed to be as generally usable as possible. The sword could open crates as well (Ok, well much better) than a crowbar could and reduced the need to carry two things. Many weapons came with multiple ammunition types, allowing you to customise your load out to the kind of game you wanted to play. Other nice features included the fact that there very few situations of ‘spontaneous creation’, where monsters appeared at some point in a scripted scene, which would have enforced a certain approach. If you were crawling in somewhere from completely the wrong side, everything would be there and ready, rather than all spontaneously reappearing when you happened to approach from the ‘triggering’ side.

In short, it felt like a real world. (With the usual caveat regarding it being a real world where you are a killer cyborg in 2052.)

The big advantage of this is that you feel a great deal of freedom in your planning and implementation and, combined with the fact that the game reacts and changes to the decisions that you make, this makes the endings of the game feel very personal – when you finally choose between the three possible endings, you do so feeling like the game is actually going along with the persona that you have set up. This increases the level of engagement, achievement and enjoyment.

One of Mark Guzdial’s recent posts talked about the importance of good design when it comes to constructing instructional materials and I couldn’t agree more. Good design at the start, with a clear idea of what you’re trying to achieve, allows you to build a consistent experience that will allow you and your students to achieve your objectives. Deus Ex is, in my opinion, considered one of the best games of the 21st century because it started from a simple and clear design document that was set out to maximise the degree of influence that the player could feel in the game – everyone who plays Deus Ex takes their own path through it, has their own experience and gets something slightly different out of it.

I’m not saying it’s that easy for educational design as a global issue, but it is a very good reminder of why we should be doing good design at the very beginning of our courses!

Wrath of Kohn: Well, More Thoughts on “Punished by Rewards”

Posted: July 16, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, educational problem, feedback, games, higher education, in the student's head, measurement, principles of design, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, universal principles of design, work/life balance, workload 1 CommentYesterday, I was discussing my reading of Alfie Kohn’s “Punished by Rewards” and I was talking about a student focus to this but today I want to talk about the impact on staff. Let me start by asking you to undertake a quick task. Let’s say you are looking for a new job, what are the top ten things that you want to get from it? Write them down – don’t just think about them, please – and have them with you. I’ll put a picture of Kohn’s book here to stop you looking ahead. 🙂

It’s ok, I’ll wait. Written your list?

How far up the list was “Money”? Now, if you wrote money in the top three, I want you to imagine that this new job will pay you a fair wage for what you’re going to do and you won’t have any money troubles. (Bit of a reach, sometimes, I know but please give it a try.) With that in mind, look at your list again.

Does the word “excellent incentive scheme” or “great bonus package” figure anywhere on that list? If it does, is it in the top half or the bottom half? If Money wasn’t top three, where was it for you?

According to Kohn, very few people actually to make money the top of their list – it tends to be things like ‘type of work’, ‘interesting job’, ‘variety’, ‘challenge’ and stuff like that. So, if that’s the case, why do so many work incentive schemes revolve around giving us money or bonuses as a reward if, for the majority of the population, it’s not the thing that we want? Well, of course, it’s easy. Giving feedback or mentoring is much harder than a $50 gift card, a $2,000 bonus or 500 shares. What’s worse is, because it’s money, it has to be allocated in an artificial scarcity environment or it’s no longer a bonus, it’s an expectation. If you didn’t do this, then the company might go bankrupt.

What if, instead, when you did something really good, you received something that made it easier for you to do all of your work as a recognition of the fact that you’re working a lot? Of course, this would require your manager to have a really good idea of what you were doing and how to improve it, as well as your company being willing to buy you that backlit keyboard with the faux-mink armrest that will let you write reports without even a twinge of arm strain. Some of this, obviously, is part of minimum workplace standards but the idea is that you get something that reflects that your manager understands what you’ve done and is trying to help you to develop further. Carefully selected books, paid trips to useful training, opportunities to further display your skill – all of these are probably going to achieve more of the items on your 10-point list than money will. To quote Kohn, quoting Gruenberg (1980), “The Happy Worker: An Analysis of Educational and Occupational Differences in Determinants of Job Satisfaction”, American Journal of Sociology, 86, pp 267-8:

“Extrinsic rewards become an important determinant of overall job satisfaction only among workers for whom intrinsic rewards are relatively unavailable.”

There are, Kohn argues, many issues with incentive schemes as reward and one of these is the competitive environment that it fosters. I discussed this yesterday so I’ll move to one of the other, which is focusing on meeting the requirements for reward at the expense of quality and in a way that is as safe as possible. Let me give you an example that I recently encountered outside of work: Playing RockBand or SingStar (music games that score your performance). Watch me and my friends who actually sing playing a singing game: yes, we notice the score, but we don’t care about the score. We interpret, we mess around, we occasionally affect the voices of the Victorian-era female impersonator characters from Little Britain. Then watch other groups of people who are playing the game to make the highest score. They don’t interpret. They don’t harmonise spontaneously. In many cases, they barely even sing and focus on making the minimum tunefully accurate noise possible at exactly the right time, having learned the sequence, to achieve the highest score. The quality of the actual singing is non-existent, because this isn’t singing, it’s score-maximisation. Similarly, risk taking has been completely removed. (As an aside, I have excellent pitch and, to my ears, most people who try to maximise their score sound out of tune because they are within the tolerances that the game accepts, but by choosing not to actually sing, there is no fundamental thread of musicality that runs through their performance. I once saw a professional singer deliver a fantastic version of a song, only to be rated as mediocre by the system,)

On Saturday, my wife and I went to the Melbourne-based Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) to attend the Game Masters gaming exhibition. It was fantastic, big arcade section and tons of great stuff dedicated to gaming. (Including the design document for Deus Ex!) There were lots of games to play, including SingStar (Scored karaoke), RockBand (multi-instrument band playing with feedback and score) and some dancing games. Going past RockBand, Katrina pointed out how little fun the participants appeared to be having and, on looking at it, it was completely true. The three boys in there were messing around with pseudo-musical instruments but, rather than making a loud and joyful noise, they were furrowed of brow and focused on doing precisely the right things at the right times to get positive feedback and a higher score. Now, there are many innovations emerging in this space and it is now possible to explore more and actually take some risks for innovation, but from industry and from life experience, it’s pretty obvious that your perception of what you should be doing and where the reward is going to come from make a huge difference.

If your reward is coming from someone/something else, and they set a bar of some sort, you’re going to focus on reaching that bar. You’re going to minimise the threats to not reaching that bar by playing it safe, colouring inside the lines, trying to please the judge and then, if you don’t get that reward, you’re far more likely to stop carrying out that activity, even if you loved it before. And, boy, if you don’t get that reward, will you feel punished.

I’m not saying Kohn is 100% correct, because frankly I don’t know and I’m not a behaviourist, but a lot of this rings true from my own experience and his use of the studies included in his book, as well as the studies themselves, are very persuasive. I look forward to some discussion on these points!

The Big Picture and the Drug of Easy Understanding: Part II (Eclectic Boogaloo)

Posted: July 10, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, fiero, games, higher education, measurement, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, universal principles of design Leave a commentIn yesterday’s post, I talked about the desire to place work into some sort of grand scheme, referring to movies and films, and illustrating why it’s hard to guarantee consistency from a sketch of your strategy unless you implement everything before you make it available to people. While building upon previous work is very useful, as I’m doing now, if you want to keep later works short by referring back to a shared context established in a previous work, it does make you susceptible to inconsistency if a later work makes you realise that assumptions in a previous work were actually wrong. As I noted in yesterday’s post, I’m actually writing these posts side by side and scheduling them for later, to ensure that I don’t make any more mistakes than I have to, which I can’t easily correct because the work is already displayed.

Strategic approaches to the construction of long term and complex works are essential, but a strategic plan needs to be sufficiently detailed in order to guide the works produced from it. You might get away with an abstract strategy if you produce all of the related works at one time and view them together. But, assuming that works are so long term that they can’t be produced in one sitting, you don’t want to have to seriously revise previous productions or, worse, change the strategy. This is particularly damaging when you are working with students because any significant change to the knowledge construction that you’ve been working with is going to cost you a lot of credibility and risk a high level of disengagement. Students will tolerate an amount of honest mistake, assuming that you are honest and that it is a mistake, but they tend to be very judgmental regarding poor time planning and what they perceive as laziness.

And that, in my opinion, is completely fair because we tend not to allow them poor time planning either. Going into an examination with a misunderstanding of the details of the overlying strategy will result in a non-negotiable fail, not extended understanding from the marking groups who are looking at examination performance. For me, this is an issue of professional ethics in that a consistent and fair delivery of teaching materials will facilitate learning, firstly by keeping the knowledge pathways ‘clean’ but also by establishing a relationship that you are working as hard to be fair to the student as you can, hence their effort is not wasted and you establish a bond of trust.

Now while I would love to say that this means that I have written every lecture completely before starting a new course, this would not be the truth. But this does mean that my strategic planning for new works and knowledge is broken down to a fairly fine grain plan before I start the course running. I wrote a new course last semester and the overall course had been broken up by area, sub-area, learning outcome and was built with all practicals, tutorials and activities clearly indicated. I had also spent a long time identifying the design of the overall course and the focus that we would be taking throughout, down to the structure of every lecture. When it came to writing the lectures themselves, I knew which lectures would contain ‘achievement’ items (the drug aspect where students get a buzz from the “A-ha!” moment), I knew where the pivotal points were and I’d also spent some time working out which skills I could expect in this group, and which skills later courses would expect from them.

We do have a big picture for teaching our students, in that they are part of a particular implementation of a degree that will qualify them in such-and-such a discipline. We can see the discipline syllabi, current learning and teaching practices, our local requirements and the resources that we have to carry all of this out. But this is no longer a strategy and, the more I worked with things, the more I realised that I had produced a tactical (or operational) plan for each week of the lectures – and I had to be diligent about this because one third of my lectures were being given by someone who was a new lecturer. So, on top of all the planning, every lecture had to be self-contained and instructionally annotated so that a new lecturer, with some briefing from me, could carry it out. And it all had to fit together so that structurally, semantically and stylistically, it all looked like one smooth flow.

Had I left the strategic planning to one side, in either not pursuing it or in leaving it too late, or had I not looked at all of the strategic elements that I had to consider, then my operational plan for each week would have been ad hoc or non-existent. Worse, it may have been an unattainable plan; a waste of my time and the students’ efforts. We have far less excuse than George Lucas does for pretending that Star Wars was part of some enormous nine movie vision – although, to be fair, it doesn’t mean that this wasn’t somewhere in his head, but it obviously wasn’t sufficiently well plotted to guarantee a required level of consistency to make us really believe that statement.

The Big Picture is a framing that helps certain creative works drag you in and make more money, whereas in other words it is a valid structure that supports and develops consistency within a shared context. Our work as educators fits squarely into the final category. Without a solid plan, we risk making short-sighted decisions that please us or the student with ‘easy’ reward activities or the answers that come to hand at the time.

I’m not saying that certain elements have to be left out of our teaching, or that we have to be rigid in an inflexible structure, but consistency and reliability are two very important aspects of gaining student trust and, if holding it together over six serial instalments is too hard for Stephen King, then trying to achieve this, without some serious and detailed planning, over 36 lectures spanning four months is probably too much for most of us. The Big Picture, for us, is something that I believe we can find and use very effectively to make our teaching even better, effectively reducing our workload throughout the semester because we don’t have to carry out massive revisions or fixes, with a little more investment of time up front.

(Afterthought: I had no idea that Dr Steele has released an album called “Eclectic Boogaloo”. I was riffing on the old “Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo” thing. In my defence, it was the 80s and we all looked like this:

)

The Big Picture and the Drug of Easy Understanding: Part I

Posted: July 9, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, education, educational problem, feedback, fiero, games, Generation Why, higher education, measurement, principles of design, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design Leave a commentThere is a tendency to frame artistic works such as films and books inside a larger frame. It’s hard to find a fantasy novel that isn’t “Book 1 of the Mallomarion Epistemology Cycle” or a certain type of mainstream film that doesn’t relate to a previous film (as II, III or higher) or as a re-interpretation of a film in the face of another canon (the re-re-reboot cycle). There are still independent artistic endeavours within this, certainly, but there is also a strong temptation to assess something’s critical success and then go on to make another version of it, in an attempt to make more money. Some things were always multi-part entities in the planning and early stages (such as the Lord of the Rings books and hence movies), some had multiplicity thrust upon them after unlikely success (yes, Star Wars, I’m looking at you, although you are strangely similar to Hidden Fortress so you aren’t even the start point of the cycle).

From a commercial viewpoint, selling something that only sells itself is nowhere near as interesting as selling something that draws you into a consumption cycle. This does, however, have a nasty habit of affecting the underlying works. You only have to look at the relative length of the Harry Potter books, and the quality of editing contained within, to realise that Rowling reached a point where people stopped cutting her books down – even if that led to chapters of aimless meandering in a tent in later books. Books one to three are, to me, far, far better than the later ones, where commercial influence, the desire to have a blockbuster and the pressure of producing works that would continue to bring in more consumers and potentially transfer better to the screen made some (at least for me) detrimental changes to the work.

This is the lure of the Big Picture – that we can place everything inside a grand plan, a scheme laid out from the beginning, and it will validate everything that has gone before, while including everything that is yet to come. Thus, all answers will be given, our confusion will turn to understanding and we will get that nice warm feeling from wrapping everything up. In many respects, however, the number of things that are actually developed within a frame like this, and remain consistent, is very small. Stephen King experimented with serial writing (short instalments released regularly) for a while, including the original version of “The Green Mile”. He is a very talented and experienced writer and he still found that he had made some errors in already published instalments that he had to either ignore or correct in later instalments. Although he had a clear plan for the work, he introduced errors to public view and he discovered them in later full fleshings of the writing. He makes a note in the book of the Green Mile that one of the most obvious, to him, was having someone scratch their nose with their hand while in a straitjacket. Not having all of the work to look at leaves you open to these kinds of errors, even where you do have a plan, unless you have implemented everything fully before you deploy it.

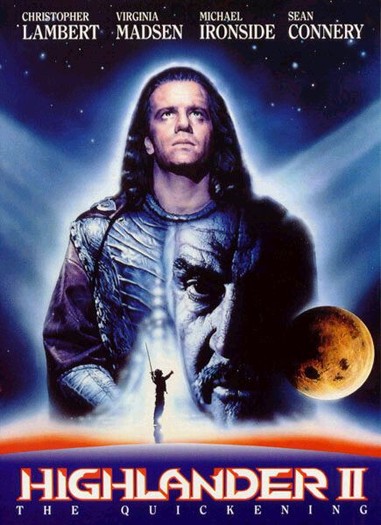

So it’s no surprise that we’re utterly confused by the prequels to Star Wars, because (despite Lucas’ protestations), it is obvious that there was not even a detailed sketch of what would happen. The same can be said of the series “Lost” where any consistency that was able to be salvaged from it was a happy accident, as the writers had no idea what half of the early things actually were – it just seemed cool. And, as far as I’m concerned, there is no movie called Highlander 2.

(I should note that this post is Part 1 of 2, but I am writing both parts side by side, to try and prevent myself from depending in Part 2 upon something that I got wrong in Part 1.)

To take this into an educational space, it is tempting to try and construct learning from a sequence of high-reward moments of understanding. Our students are both delighted and delightful when they “get” something – it’s a joy to behold and one of the great rewards of the teacher. But, much like watching TED talks every day won’t turn you into a genius, it is the total construction of the learning experience that provides something that is consistent throughout and does not have to endure any unexpected reversals or contradictions later on. We don’t have a commercial focus here to hook the students. Instead, we want to keep them going throughout the necessary, but occasionally less exciting, foundation work that will build them up to the point where they are ready to go, in Martin Gardner’s words, “A-ha!”

My problem arises if I teach something that, when I develop a later part of the course, turns out to not provide a complete basis, reinterprets the work in a way that doesn’t support a later point or places an emphasis upon the wrong aspect. Perhaps we are just making the students look at the wrong thing, only to realise later that had we looked at the details, rather than our overall plan, we would have noticed this error. But, now, it is too late and the wrong message is out there.

This is one of the problems of gamification, as I’ve referred to previously, in that we focus on the drug of understanding as a fiero (fierce joy) moment to the exclusion of the actual education experience that the game and reward elements should be reinforcing. This is one of the problems of stating that something is within a structure when it isn’t: any coincidence of aims or correlation of activities is a happy accident, serendipity rather than strategy.

In tomorrow’s post, I’ll discuss some more aspects of this and the implications that I believe it has for all of us as educators.

Time Banking III: Cheating and Meta-Cheating

Posted: June 13, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, blogging, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, ethics, games, higher education, in the student's head, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking Leave a commentOne of the problems with setting up any new marking system is that, especially when you’re trying to do something a bit out of the ordinary, you have to make sure that you don’t produce a system that can be gamed or manipulated to let people get an unfair advantage. (Students are very resourceful when it comes to this – anyone who has received a mysteriously corrupted Word document of precisely the right length and with enough relevant strings to look convincing, on more than one occasion from the same student and they then are able to hand up a working one the next Monday, knows exactly what I’m talking about.)

As part of my design, I have to be clear to the students what I do and don’t consider to be reasonable behaviour (returning to Dickinson and McIntyre, I need to be clear in my origination and leadership role). Let me illustrate this with an anecdote from decades ago.

In the early 90s, I helped to write and run a number of Multi User Dungeons (MUDs) – the text-based fore-runners of the Massively Multiplayer On-line Role Playing Games, such as World of Warcraft. The games had very little graphical complexity and we spent most of our time writing the code that drove things like hitting orcs with swords or allowing people to cast spells. Because of the many interactions between the software components in the code, it was possible for unexpected things to happen – not just bugs where code stopped working but strange ‘features’ where things kept working but in an odd way. I knew a guy, let’s call him K, who was a long-term player of MUDs. If the MUD was any good, he’d not only played it, he’d effectively beaten it. He knew every trick, every lurk, the best way to attack a monster but, more interestingly, he had a nose for spotting errors in the code and taking advantage of them. One time, in a game we were writing, we spotted K walking around with something like 20-30 ’empty’ water bottles on him. (As game writers, wizards, we could examine any object in the game, which included seeing what players were carrying.)

This was weird. Players had a limited amount of stuff that they could carry, and K should have had no reason to carry those bottles. When we examined him, we discovered that we’d made an error in the code so that, when you drank from a bottle and emptied it, the bottle ended up weighing LESS THAN NOTHING. (It was a text game and our testing wasn’t always fantastic – I learnt!) So K was carrying around the in-game equivalent of helium balloons that allowed him to carry a lot more than he usually would.

Of course, once we detected it, we fixed the code and K stopped carrying so many empty bottles. (Although, I have no doubt that he personally checked each and every container we put into the game from that point on to see if could get it to happen again.) Did we punish him? No. We knew that K would need some ‘flexibility’ in his exploration of the game, knowing that he would press hard against the rubber sheet to see how much he could bend reality, but also knowing that he would spot problems that would take us weeks or months of time to find on our own. We took him into our new and vulnerable game knowing that if he tried to actually break or crash the game, or share the things he’d learned, we’d close off his access. And he knew that too.

Had I placed a limit in play that said “Cheating detected = Immediate Booting from the game”, K would have left immediately. I suspect he would have taken umbrage at the term ‘cheating’, as he generally saw it as “this is the way the world works – it’s not my fault that your world behaves strangely”. (Let’s not get into this debate right now, we’re not in the educational plagiarism/cheating space right now.)

We gave K some exploration space, more than many people would feel comfortable with, but we maintained some hard pragmatic limits to keep things working and we maintained the authority required to exercise these limits. In return, K helped us although, of course, he played for the fun of the game and, I suspect, the joy of discovering crazy bugs. However, overall, this approach saved us effort and load, and allowed us to focus on other things with our limited resources. Of course, to make this work required careful orientation and monitoring on our behalf. Nothing, after all, comes for free.

If I’d asked K to fill out forms describing the bugs he’d found, he’d never have done it. If I’d had to write detailed test documents for him, I wouldn’t have had time to do anything else. But it also illustrates something that I have to be very cautious of, which I’ve embodied as the ‘no cheating/gaming’ guideline for Time Banking. One of the problems with students at early development stages is that they can assume that their approach is right, or even assert that their approach is the correct one, when it is not aligned with our goals or intentions at all. Therefore, we have to be clear on the goals and open about our intentions. Given that the goal of Time Banking is to develop mature approach to time management, using the team approach I’ve already discussed, I need to be very clear in the guidance I give to students.

However, I also need to be realistic. There is a possibility that, especially on the first run, I introduce a feature in either the design or the supporting system that allows students to do something that they shouldn’t. So here’s my plan for dealing with this:

- There is a clear no-cheating policy. Get caught doing anything that tries to subvert the system or get you more hours in any other way than submitting your own work early and it’s treated as a cheating incident and you’re removed from the time bank.

- Reporting a significant fault in the system, that you have either deduced, or observed, is worth 24 hours of time to the first person who reports it. (Significant needs definition but it’s more than typos.)

I need the stick. Some of my students need to know that the stick is there, even if the stick is never needed, but I really can’t stand the stick. I have always preferred the carrot. Find me a problem and you get an automatic one-day extension, good for any assignment in the bank. Heck, I could even see my way clear to making this ‘liftable’ hours – 24 hours you can hand on to a friend if you want. If part of your team thinking extends to other people and, instead of a gifted student handing out their assignment, they hand out some hours, I have no problem with that. (Mr Pragmatism, of course, places a limit on the number of unearned hours you can do this with, from the recipient’s, not the donor’s perspective. If I want behaviour to change, then people have to act to change themselves.)

My design needs to keep the load down, the rewards up but, most importantly, the rewards have to move the students towards the same goals as the primary activity or I will cause off-task optimisation and I really don’t want to do that.

I’m working on a discussion document to go out to people who think this is a great idea, a terrible idea, the worst idea ever, something that they’d like to do, so that I can bring all of the thoughts back together and, as a group of people dedicated to education, come up with something that might be useful – OR, and it’s a big or, come up with the dragon slaying notion that kills time banking stone dead and provides the sound theoretical and evidence-based support as to why we must and always should use deadlines. I’m prepared for one, the other, both or neither to be true, along with degrees along the axis.