A Break in the Silence: Time to Tell a Story

Posted: December 30, 2013 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, design, education, feedback, games, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, resources, storytelling, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, work/life balance, workload 2 CommentsIt has been a while since I last posted here but that is a natural outcome of focusing my efforts elsewhere – at some stage I had to work out what I had time to do and do it. I always tell my students to cut down to what they need to do and, once I realised that the time I was spending on the blog was having one of the most significant impacts on my ability to juggle everything else, I had to eat my own dogfood and cut back on the blog.

Of course, I didn’t do it correctly because instead of cutting back, I completely cut it out. Not quite what I intended but here’s another really useful piece of information: if you decide to change something then clearly work out how you are going to change things to achieve your goal. Which means, ahem, working out what your goals are first.

I’ve done a lot of interesting stuff over the last 6 months, and there are more to come, which means that I do have things to write about but I shall try and write about one a week as a minimum, rather than one per day. This is a pace that I hope to keep up and one that will mean that more of you will read more of what I write, rather than dreading the daily kiloword delivery.

I’ll briefly reflect here on some interesting work and seminars I’ve been looking at on business storytelling – taking a personal story, something authentic, and using it to emphasise a change in business behaviour or to emphasise a characteristic. I recently attended one of the (now defunct) One Thousand and One’s short seminars on engaging people with storytelling. (I’m reading their book “Hooked” at the moment. It’s quite interesting and refers to other interesting concepts as well.) I realise that such ideas, along with many of my notions of design paired with content, will have a number of readers peering at the screen and preparing a retort along the lines of “Storytelling? STORYTELLING??? Whatever happened to facts?”

Why storytelling? Because bald facts sometimes just don’t work. Without context, without a way to integrate information into existing knowledge and, more importantly, without some sort of established informational relationship, many people will ignore facts unless we do more work than just present them.

How many examples do you want: Climate Change, Vaccination, 9/11. All of these have heavily weighted bodies of scientific evidence that states what the answer should be, and yet there is powerful and persistent opposition based, largely, on myth and storytelling.

Education has moved beyond the rationing out of approved knowledge from the knowledge rich to those who have less. The tyrannical informational asymmetry of the single text book, doled out in dribs and drabs through recitation and slow scrawling at the front of the classroom, looks faintly ludicrous when anyone can download most of the resources immediately. And yet, as always, owning the book doesn’t necessarily teach you anything and it is the educator’s role as contextualiser, framer, deliverer, sounding board and value enhancer that survives the death of the drip-feed and the opening of the flood gates of knowledge. To think that storytelling is the delivery of fairytales, and that is all it can be, is to sell such a useful technique short.

To use storytelling educationally, however, we need to be focused on being more than just entertaining or engaging. Borrowing heavily from “Hooked”, we need to have a purpose in telling the story, it needs to be supported by data and it needs to be authentic. In my case, I have often shared stories of my time in working with computer networks, in short bursts, to emphasise why certain parts of computer networking are interesting or essential (purpose), I provide enough information to show this is generally the case (data) and because I’m talking about my own experiences, they ring true (authenticity).

If facts alone could sway humanity, we would have adopted Dewey’s ideas in the 1930s, instead of rediscovering the same truths decade after decade. If only the unembellished truth mattered, then our legal system would look very, very different. Our students are surrounded by talented storytellers and, where appropriate, I think those ranks should include us.

Now, I have to keep to the commitment I made 8 months ago, that I would never turn down the chance to have one of my cats on my lap when they wanted to jump up, and I wish you a very happy new year if I don’t post beforehand.

Let’s not turn “Chalk and Talk” into “Watch and Scratch”

Posted: July 1, 2013 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, higher education, moocs, principles of design, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, tools, universal principles of design 1 CommentWe are now starting to get some real data on what happens when people “take” a MOOC (via Mark’s blog). You’ll note the scare quotes around the word “take”, because I’m not sure that we have really managed to work out what it means to get involved in a course that is offered through the MOOC mechanism. Or, to be more precise, some people think they have but not everyone necessarily agrees with them. I’m going to list some of my major concerns, even in the face of the new clickstream data, and explain why we don’t have a clear view of the true value/approaches for MOOCs yet.

- On-line resources are not on-line courses and people aren’t clear on the importance of an overall educational design and facilitation mechanism. Many people have mused on this in the past. If all the average human needed was a set of resources and no framing or assistive pedagogy then our educational resources would be libraries and there would be no teachers. While there are a number of offerings that are actually courses, applying the results of the MIT 6.002x to what are, for the most part, unstructured on-line libraries of lecture recordings is not appropriate. (I’m not even going to get into the cMOOC/xMOOC distinction at this point.) I suspect that this is just part of the general undervaluing of good educational design that rears its head periodically.

- Replacing lectures with on-line lectures doesn’t magically improve things. The problem with “chalk and talk”, where it is purely one-way with no class interaction, is that we know that it is not an effective way to transfer knowledge. Reading the textbook at someone and forcing them to slowly transcribe it turns your classroom into an inefficient, flesh-based photocopier. Recording yourself standing in front a class doesn’t automatically change things. Yes, your students can time shift you, both to a more convenient time and at a more convenient speed, but what are you adding to the content? How are you involving the student? How can the student benefit from having you there? When we just record lectures and put them up there, then unless they are part of a greater learning design, the student is now sitting in an isolated space, away from other people, watching you talk, and potentially scratching their head while being unable to ask you or anyone else a question. Turning “chalk and talk” into “watch and scratch” is not an improvement. Yes, it scales so that millions of people can now scratch their heads in unison but scaling isn’t everything and, in particular, if we waste time on an activity under the illusion that it will improve things, we’ve gone backwards in terms of quality for effort.

- We have yet to establish the baselines for our measurement. This is really important. An on-line system us capable of being very heavily tracked and it’s not just links. The clickstream measurements in the original report record what people clicked on as they worked with the material. But we can only measure that which is set up for measurement – so it’s quite hard to compare the activity in this course to other activities that don’t use technology. But there are two subordinate problems to this (and I apologise to physicists for the looseness of the following) :

- Heisenberg’s MOOC: At the quantum scale, you can either tell where something is or what it is doing – the act of observation has limits of precision. Borrowing that for the macro scale: measure someone enough and you’ll see how they behave under measurement but the measurements we pick tend to fall into the stage they’ve reached or the actions they’ve taken. It’s very complex to combine quantitative and qualitative measures to be able to map someone’s stage and their comprehension/intentions/trajectory. You don’t have to accept arguments based on the Hawthorne Effect to understand why this does not necessarily tell you much about unobserved people. There are a large number of people taking these courses out of curiosity, some of whom already have appropriate qualifications, with only 27% the type of student that you would expect to see at this level of University. Combine that with a large number of researchers and curious academics who are inspecting each other’s courses, I know of at least 12 people in my own University taking MOOCs of various kinds to see what they’re like, and we have the problem that we are measuring people who are merely coming in to have a look around and are probably not as interested in the actual course. Until we can actually shift MOOC demography to match that of our real students, we are always going to have our measurements affected by these observers. The observers might not mind being heavily monitored and observed, but real students might. Either way, numbers are not the real answer here – they show us what but there is still too much uncertainty in the why and the how.

- Schrödinger’s MOOC: Oh, that poor reductio ad absurdum cat. Does the nature of the observer change the behaviour of the MOOC and force it to resolve one way or another (successful/unsuccessful)? If so, how and when? Does the fact of observation change the course even more than just in enrolments and uncertainty of validity of figures? The clickstream data tells us that the forums are overwhelmingly important to students, with 90% of people who viewed threads without commenting, and only 3% of total students enrolled every actually posted anything in a thread. What was the make-up of that 3% and was it actual students or the over-qualified observers who then provided an environment that 90% of their peers found useful?

- Numbers need context and unasked questions give us no data: As one example, the authors of the study were puzzled that so few people had logged in from China, which surprised them. Anyone who has anything to do with network measurement is going to be aware that China is almost always an outlier in network terms. My blog, for example, has readers from around the world – but not China. It’s also important to remember that any number of Chinese network users will VPN/SSH to hosts outside China to enjoy unrestricted search and network access. There may have been many Chinese people (who didn’t self-identify for obvious reasons) who were using proxies from outside China. The numbers on this particular part of the study do not make sense unless they are correctly contextualised. We also see a lack of context in the reporting on why people were doing the course – the numbers for why people were doing it had to be augmented from comments in the forum that people ‘wanted to see if they could make it through an MIT course’. Why wasn’t that available from the initial questions?

- We don’t know what pass/fail is going to look like in this environment. I can’t base any MOOC plans of my own on how people respond to a MIT-branded course but it is important to note that MIT’s approach was far more than “watch and scratch”, as is reflected by their educational design in providing various forms of materials, discussions forums, homework and labs. But still, 155,000 people signed up for this and only 7,000 received certificates. 2/3 of people who registered then went on to do nothing. I don’t think that we can treat a success rate of less than 5% as a success rate. Even where we say that 2/3 dropped out, this still equates to a pass rate under 14%. Is that good? Is that bad? Taking everything into account from above, my answer is “We don’t know.” If we get 17% next time, is that good or bad? How do we make this better?

- The drivers are often wrong. Several US universities have gone on the record to complain about undermining their colleagues and have refused to take part in MOOC-related activities. The reasons for this vary but the greatest fear is that MOOCs will be used to reduce costs by replacing existing lecturing staff with a far smaller group and using MOOCs to handle the delivery. From a financial argument, MOOCs are astounding – 155,000 people contacted for the cost of a few lecturers. Contrast that with me teaching a course to 100 students. If we look at it from a quality perspective, and dealing with all of the points so far, we have no argument to say that MOOCs are as good as our good teaching – but we do know that they are easily as good as our bad teaching. But from a financial perspective? MOOC is king. That is, however, not how we guarantee educational quality. Of course, when we scale, we can maintain quality by increasing resources but this runs counter to a cost-saving argument so we’re almost automatically being prevented from doing what is required to make the large scale course work by the same cost driver that led to its production in the first place!

- There are a lot of statements but perhaps not enough discussion. These are trying times for higher education and everyone wants an edge, more students, higher rankings, to keep their colleagues and friends in work and, overall, to do the right thing for their students. Senior management, large companies, people worried about money – they’re all talking about MOOCs as if they are an accepted substitute for traditional approaches – at the same time as we are in deep discussion about which of the actual traditional approaches are worthwhile and which new approaches are going to work better. It’s a confusing time as we try to handle large-scale adoption of blended learning techniques at the same time people are trying to push this to the large scale.

I’m worried that I seem to be spending most of my time explaining what MOOCs are to people who are asking me why I’m not using a MOOC. I’m even more worried when I am still yet to see any strong evidence that MOOCs are going to provide anything approaching the educational design and integrity that has been building for the past 30 years. I’m positively terrified when I see corporate providers taking over University delivery before we have established actual measurable quality and performance guidelines for this incredibly important activity. I’m also bothered by statements found at the end of the study, which was given prominence as a pull quote:

[The students] do not follow the norms and rules that have governed university courses for centuries nor do they need to.

I really worry about this because I haven’t yet seen any solid evidence that this is true, yet this is exactly the kind of catchy quote that is going to be used on any number of documents that will come across my desk asking me when I’m going to MOOCify my course, rather than discussing if and why and how we will make a transition to on-line blended learning on the massive scale. The measure of MOOC success is not the number of enrolees, nor is it the number of certificates awarded, nor is it the breadth of people who sign up. MOOCs will be successful once we have worked out how to use this incredibly high potential approach to teaching to deliver education at a suitably high level of quality to as many people as possible, at a reduced or even near-zero cost. The potential is enormous but, right now, so is the risk!

Another semester, more lessons learned (mostly by me).

Posted: June 16, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, plagiarism, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design Leave a commentI’ve just finished the lecturing component for my first year course on programming, algorithms and data structures. As always, the learning has been mutual. I’ve got some longer posts to write on this at some time in the future but the biggest change for this year was dropping the written examination component down and bringing in supervised practical examinations in programming and code reading. This has given us some interesting results that we look forward to going through, once all of the exams are done and the marks are locked down sometime in late July.

Whenever I put in practical examinations, we encounter the strange phenomenon of students who can mysteriously write code in very short periods of time in a practical situation very similar to the practical examination, but suddenly lose the ability to write good code when they are isolated from the Internet, e-Mail and other people’s code repositories. This is, thank goodness, not a large group (seriously, it’s shrinking the more I put prac exams in) but it does illustrate why we do it. If someone has a genuine problem with exam pressure, and it does occur, then of course we set things up so that they have more time and a different environment, as we support all of our students with special circumstances. But to be fair to everyone, and because this can be confronting, we pitch the problems at a level where early achievement is possible and they are also usually simpler versions of the types of programs that have already been set as assignment work. I’m not trying to trip people up, here, I’m trying to develop the understanding that it’s not the marks for their programming assignments that are important, it’s the development of the skills.

I need those people who have not done their own work to realise that it probably didn’t lead to a good level of understanding or the ability to apply the skill as you would in the workforce. However, I need to do so in a way that isn’t unfair, so there’s a lot of careful learning design that goes in, even to the selection of how much each component is worth. The reminder that you should be doing your own work is not high stakes – 5-10% of the final mark at most – and builds up to a larger practical examination component, worth 30%, that comes after a total of nine practical programming assignments and a previous prac exam. This year, I’m happy with the marks design because it takes fairly consistent failure to drop a student to the point where they are no longer eligible for redemption through additional work. The scope for achievement is across knowledge of course materials (on-line quizzes, in-class scratchy card quizzes and the written exam), programming with reference materials (programming assignments over 12 weeks), programming under more restricted conditions (the prac exams) and even group formation and open problem handling (with a team-based report on the use of queues in the real world). To pass, a student needs to do enough in all of these. To excel, they have to have a good broad grasp of theoretical and practical. This is what I’ve been heading towards for this first-year course, a course that I am confident turns out students who are programmers and have enough knowledge of core computer science. Yes, students can (and will) fail – but only if they really don’t do enough in more than one of the target areas and then don’t focus on that to improve their results. I will fail anyone who doesn’t meet the standard but I have no wish to do any more of that than I need to. If people can come up to standard in the time and resource constraints we have, then they should pass. The trick is holding the standard at the right level while you bring up the people – and that takes a lot of help from my colleagues, my mentors and from me constantly learning from my students and being open to changing the learning design until we get it right.

Of course, there is always room for improvement, which means that the course goes back up on blocks while I analyse it. Again. Is this the best way to teach this course? Well, of course, what we will do now is to look at results across the course. We’ll track Prac Exam performance across all practicals, across the two different types of quizzes, across the reports and across the final written exam. We’ll go back into detail on the written answers to the code reading question to see if there’s a match for articulation and comprehension. We’ll assess the quality of response to the exam, as well as the final marked outcome, to tie this back to developmental level, if possible. We’ll look at previous results, entry points, pre-University marks…

And then we’ll teach it again!

The Continuum of Ethical Challenge: Why the Devil Isn’t Waiting in the Alleyway and The World is Harder than Bioshock.

Posted: June 15, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, community, curriculum, design, education, educational research, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentThis must be a record for a post title but I hope to keep the post itself shortish. Years ago, when I was still at school, a life counsellor (who was also a pastor) came to talk to us about life choices and ethics. He was talking about the usual teen cocktail: sex, drugs and rebellion.. However, he made an impression on me by talking about his early idea of temptation. Because of the fire and brimstone preaching he’d grown up with, he half expected temptation to take the form of the Devil, beckoning him into an alleyway to take an illicit drag on a cigarette. As he grew up, and grew wiser, he realised that living ethically was really a constant set of choices, interlocking or somewhat dependant, rather than an easy life periodically interrupted by strictly defined challenges that could be overcome with a quick burst of willpower.

I recently started replaying the game Bioshock, which I have previously criticised elsewhere, and was struck by the facile nature of the much-vaunted ethical aspect to game play. For those who haven’t played it, you basically have a choice between slaughtering or saving little girls – apart from that, you have very little agency or ability to change the path you’re on. In fact, rather than provide you with the continual dilemma of whether you should observe, ignore or attack the inhabitants of the game world, you very quickly realise that there are no ‘good’ people in the world (or there are none that you are actually allowed to attack, they are all carefully shielded from you) so you can reduce your ‘choices’ when encountering a figure crouching over a pram to “should I bludgeon her to death, or set her on fire and shoot her in the head”. (It’s ok, if you try anything approaching engagement, she will try and kill you.) In fact, one of the few ‘innocents’ in the game is slaughtered in front of you while you watch impotently. So your ethical engagement is restricted, at very distinctly defined intervals, to either harvesting or rescuing the little girls who have been stolen from orphanages and turned into corpse scavenging monsters. This is as ridiculous as the intermittent Devil in the alleyway, in fact, probably more so!

I completely agree with that counsellor from (goodness) 30 years ago – it would be a nonsense to assume that tests of our ethics can be conveniently compartmentalised to a time when our resolve is strong and can be so easily predicted. The Bioshock model (or models like it, such as Call of Duty 4, where everyone is an enemy or can’t be shot in a way that affects our game beyond a waggled finger and being taken back to a previous save) is flawed because of the limited extent of the impact of the choices you make – in fact, Bioshock is particularly egregious because the ‘outcome’ of your moral choice has no serious game impact except to show you a different movie at the end. Before anyone says “it’s only a game”, I agree, but they were the ones who imposed the notion that this ethical choice made a difference. Games such as Deus Ex gave you very much un-cued opportunities to intervene or not – with changes to the game world depending on what happened. As a result, people playing Deus Ex had far more moral engagement with the game and everyone I’ve spoken to felt as if they were making the choices that led to the outcome: autonomy, mastery and purpose anyone? That was in 2000 – very few games actually see the world as one that you can influence (although some games are now coming up to par on this).

I think about this a lot for my learning design. While my students may recognise ethical choices in the real world, I am always concerned that a learning design that reduces their activities to high stakes hurdle challenges will mimic the situation where we have, effectively, put the Devil in the alleyway and you can switch on your ‘ethical’ brain at this point. I posed a question to my students in their sample exam where I proposed that they had commissioned someone to write their software for an assignment – and them asked to think about the effect that this decision would have on their future self in terms of knowledge development, if we assumed that they would always be better prepared if they did the work themselves. This takes away the focus from the day or so leading up to an individual assignment and starts to encourage continuum thinking, where every action is take as part of a whole life of ethical actions. I’m a great believer that skills only develop with practice and knowledge only stays in your head when you reinforce it, so any opportunity to encourage further development of ethical thinking is to be encouraged!

Why You Won’t Finish This Post

Posted: June 10, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, design, education, educational problem, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, universal principles of design 3 CommentsA friend of mine on Facebook posted a link to a Slate article entitled “You Won’t Finish This Article: Why people online don’t read to the end” and it’s told me everything that I’ve been doing wrong with this blog for about the last 410 hours. Now, this doesn’t even take into account that, by linking to something potentially more interesting on a well-known site, I’ve now buried the bottom of this blog post altogether because a number of you will follow the link and, despite me asking it to appear in a new window, you will never come back to this article. (This has quite obvious implications for the teaching materials we put up, so it’s well worth a look.)

Now, on the off-chance that you did come back (hi!), we have to assume that you didn’t read all of the linked article (if you read any at all) because 28% of you ‘bounced’ immediately and didn’t actually read much at all of that page – you certainly didn’t scroll. Almost none of you read to the bottom. What is, however, amusing is that a number of you will have either Liked or forwarded a link to one or both of these pages – never having stepped through or scrolled once, but because the concept at the start looks cool. Of course, according the Slate analysis, I’ve lost over half my readers by now. Of course, this does assume the Slate layout, where an image breaks things up and forces people to scroll through. So here’s an image that will discourage almost everyone from continuing. However, it is a pretty picture:

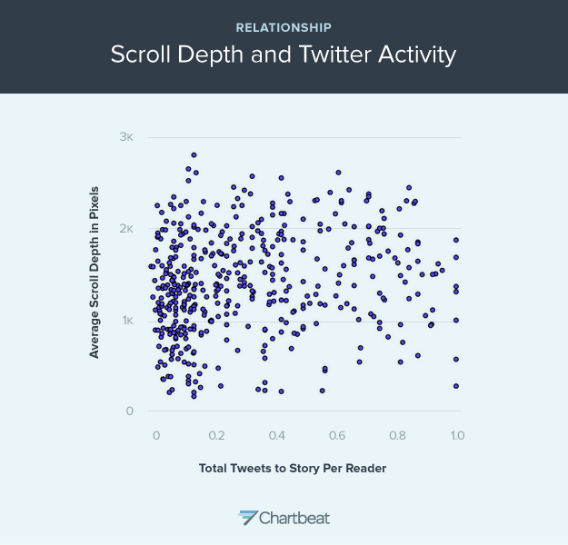

This graph shows the relationship between scroll depth and Tweet (From Slate and courtesy of Chartbeat)

What it says is that there is not an enormously strong correlation between depth of reading and frequency of tweet. So, the amount that a story is read doesn’t really tell you how much people will want to (or actually) share it. Overall, the Slate article makes it fairly clear that unless I manage to make my point in the first paragraph, I have little chance of being read any further – but if I make that first paragraph (or first images) appealing enough, any number of people will like and share it.

Of course, if people read down this far (thanks!) then they will know that I secretly start advocating the most horrible things known to humanity so, when someone finally follows their link and miraculously reads down this far, survives the Slate link out, and doesn’t end up mired in the picture swamp above, they will discover…

Oh, who am I kidding. I’ll just come back and fill this in later.

(Having stolen a time machine, I can now point out that this is yet another illustration of why we need to be thoughtful about what our students are going to do in response to on-line and hyperlinked materials rather than what we would like them to do. Any system that requires a better human, or a human to act in a way that goes against all the evidence we have of their behaviour, requires modification.)

Note to Self

Posted: May 19, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, community, education, educational problem, ethics, higher education, in the student's head, learning, marcus aurelius, meditations, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking 3 CommentsI’ve mentioned the “Meditations” of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius before – I’ve been writing this blog for over 450 hours, I’m not sure there’s anything I haven’t mentioned except my feelings on the season finale of Doctor Who, Series 7. (Eh.) Marcus Aurelius, philosopher, statesman, Roman, and Emperor wrote twelve “books” which were apparently never meant to be published. These are the private musings, notes to self, of a thoughtful man, written stoically and Stoically. When he lectures anyone, he lectures himself. He even poses questions to parts of himself: his soul, most notably.

There is much to admire in the simplicity and purpose of Marcus Aurelius’ thoughts. They are brief, because Emperors are busy people, especially when earning titles such as Germanicus (which usually involves squashing a nation state or two). They are direct, because he is talking to himself and he needs to be honest. He repeats himself for emphasis and to indicate importance, not out of forgetfulness.

Best, he writes for himself, for clarity, for the now and without thinking of a future audience.

There is a great deal to think about in this, because if you have read “Meditations”, you will know that every page contains a gem and some pages have jewels cascading from them. Yet these are the private thoughts of a person recording ways to improve himself and to keep himself in check – while he managed the Roman empire.

When I talk about improvement, I’m always trying to improve myself. When I find fault, I’ve usually found it in myself first. Yet, what a lot of words I write! Perhaps it is time to reinvestigate brevity, directness and a generosity towards the self that translates well into a kindness to strangers who might stumble upon this. The last thing I’d want to do is to stop people finding what zircons there are because the preamble is too demanding or the journey to the point too long.

Once again, I give my thanks to the writings of someone who died 2000 years ago and gave me so much to think about. Vale, Marcus Aurelius.

The Blame Game: Things were done, mistakes were made.

Posted: May 2, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, community, education, ethics, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, work/life balance, workload 5 CommentsNote: This is a re-post of something that I put up on a student discussion forum as part of one of my first-year teaching courses. I write a number of longer posts to the students to discuss some of the things that are not strictly Computer Science but can be good to know. One of my colleagues asked me to put it up in a place where he could refer to it even after the original forum was closed, so here it is.

The Irish Central Bank recently released a 10 Euro coin with a quote from James Joyce on it. Regrettably, they got the quote wrong by inserting a ‘that’ which was not in the original quote. While this is hardly newsworthy usually, I want to draw your attention to the way that the bank handled this error.

According to the bank, the coin was “an artistic representation of the author and text and not intended as a literal representation”. In fact, “the text on the Joyce coin does not correspond to the precise text as it appears in Ulysses” and “the error is regretted”.

The error is regretted? By whom? This is a delightful example of the passive voice, frequently used because people wish to avoid associating the problem with themselves. Before this coin hit the mint, people could see the graphic design and the mistake would have been there. Was the error with the original brief, the designer, the people who should have been proofing? (The actual ‘apology’ is even worse as it says “While the error is regretted” and then goes on to try and weasel out.)

Look, the blame game is seductive because people love to allocate blame and, frankly, blame assignation is not very productive because it doesn’t fix the existing problem and, worse, it rarely fixes the future problem. However, the error (in this case) did not leap into the printing presses at the mint due to run-away nanotechnology – in this case, the producing organisation (the bank) should have said “Argh, sorry. We made a mistake.” and then gone on with the offers of refunds – but more importantly, having accepted that it was their error, they would have the mental gears engaged to make changes to stop it happening again. Right now, the bank is trying to wriggle out of a mistake, which might fool people inside the bank into thinking that this is how you deal with errors – through “after the fact” passive apology, rather than taking responsibility and doing some proper proof-reading!

Years ago, I worked with a guy whose motto was “Don’t tell me that you knew it wasn’t going to work. Tell me when you think that and tell me how we’re going to fix it.” Don’t just play the blame and “I told you so” game, be active and try to fix things!

But let’s bring this closer to home. Running late for a lecture? What happened? Was the traffic really bad – or did you not allow enough time to get there, having expected really good traffic? “The traffic was awful” is a great excuse occasionally but all the time? “I didn’t allow enough time for the traffic.” What does this mean? Allow more time! Be active! Take control (if you can). If you’re on a dire bus route, then you may have to think about other ways to deal with it – perhaps you just can’t allow enough time for the awful traffic. In that case, what do you need to do in order to get the lecture content? What do you need to let the lecturer know so that we can help you?

See the difference? If “the traffic is awful” then we have no solutions because a million cars and the Adelaide City traffic computers are beyond your control. If “I have a problem with time” then it is easier to start thinking about ways to fix this that involve you.

When you think to yourself “the assignment wasn’t completed on time”, who was actually responsible for that? Note, I’m not talking about assigning blame – I’m talking about taking responsibility. If you didn’t finish the assignment on time because you didn’t start early enough, then you have started the mental processes that lead to a potential conclusion of “Oh, I should start working on things a bit earlier.” Were you sick? Should you have organised a med cert or spoken to the lecturer?

Responsibility doesn’t have to be a burden but it does give you a reason to exercise your agency, your capacity to act and to make change in the world. If all of your problems are in the passive voice, then “assignments are handed in late”, “the money ran out”, “mistakes were made” rather than “I didn’t start early enough or put enough time in or I was horribly ill and thought I could just push through”, “I spent all of my money too quickly.” and “I made a mistake”.

Obviously, a false declaration of responsibility, where you have no intention of changing, is just as bad as weasel words in the passive voice. Saying “I made a mistake” achieves nothing unless you try and change what you’re doing to stop it happening again.

When you feel that you are responsible for something, you are more likely to devote time and effort to it. The way that you describe the things in your life can help to remind you of what you are responsible for and where you can take charge and try to bring about a positive change. Language is powerful – it can really help to focus the mind on what you need to do to get the best out of everything. Use it!

(Edit: This is now in the comments but after the original post, I linked to an article on one set of steps students could use to write a real apology. You can find it here. Thanks for the nudge, Liz!)

Tell us we’re dreaming.

Posted: April 21, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, education, Generation Why, higher education, reflection, resources, thinking, work/life balance, workload 2 CommentsI recently read an opinion piece in the Australian national newspaper, the conveniently named “The Australian”, on funding school reform. The piece, entitled “School Reform must be funded” and sub-titled “But maybe we need fewer academics thinking up ways to spend our taxes”, written by Cassandra Wilkinson, identified that the coming cuts to higher education because of the apparent impossibility of paying for school reforms in any other way. No-one, sensible, is arguing that the school cuts can come out of thin air, I make explicit reference to realities such as this in my previous post, but it does appear that Cassandra is attempting to place the blame squarely on the shoulders of the academics, for this sorry state of affairs (“the growing influence of the university sector on early childhood and school education is partly responsible for the now necessary cuts to higher education.”, from the article).

It is the professionalisation of teaching, and the intervention of education academics to convince governments that early educational investment, potentially at the expense of the family unit’s role in child rearing, that has convinced governments that money must be spent here – therefore, it is our fault that our argument is leading to money coming out of our pockets. I cannot think of a more amazing piece of victim blaming, recently, but then again I generally don’t read the opinion section of The Australian!

Now, you may immediately say “You must be quoting her out of context”, here is another extract from this rather short opinion piece:

“In addition to the public costs being generated by education academics, we have public health academics driving an expensive “preventative health” agenda that includes mental health checks for kids and public advertising about the calorie content of pizza; safety academics driving up the cost of road building and tripling the price of trampolines, which now come with fencing and crash mats; and sustainability academics driving up the cost of housing.”

Not only are people concerned about education driving up the cost of education but we have increased all other prices through our short-sighted adherence to preventative health, safety and sustainability! I keep thinking that Wilkinson, who has some quiet excellent social project credentials if I have researched the correct Cassandra Wilkinson, must be making a satirical comment here but, either my humour is failing (entirely possible), she has been edited (entirely possible) or she is completely serious and we in higher education have brought doom upon our heads by dint of doing our job. The piece finishes with:

“It may well be that the real efficiency savings will derive from a university sector employing slightly fewer academics to dream up new ways for governments to spend taxpayers money.”

and whether this is intended to be satire or not, this statement does raise my hackles.

Right now, most of the academics I know are trying to dream up ways to meet our obligations to our students in terms of a high-quality, useful and valuable education under existing restrictions. The only tax spending we’re trying to do is on the things that we can barely afford to do on the monies we get. I’m assuming that Cassandra is being satirical but is just not very good at it – or is assuming the role of her namesake, in that no-one will actually take her seriously, which is a shame as the approach that she seems to be supporting is not just saying that the only place this money can come from is higher ed, but that we should shut up because of how much we’re costing decent, family-centered Australians. If only I had that many column inches in a large-scale distribution paper to put my case that, maybe, people should stop talking about what they think we’re doing, or their fuzzy memories of old Uni days and bad movies, and come down and see what we’re doing now. Shadow me for a month. Bring running shoes. But, hey, maybe I’m just lazy, soft and dreamy. How would I know?

The rich dream of luxuries, the poor dream of staples. We are dreaming of having enough to do our jobs adequately and these are not the dreams of rich people.

Maybe I’m just too tired right now to see her humour in all of this. I seriously hope that I’ve just got the wrong end of the stick, because if this is what the social progressives are saying, then we may as well close up shop now.

SIGCSE 2013: Special Session on Designing and Supporting Collaborative Learning Activities

Posted: March 31, 2013 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, reflection, resources, sigcse, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design Leave a commentKatrina and I delivered a special session on collaborative learning activities, focused on undergraduates because that’s our area of expertise. You can read the outline document here. We worked together on the underlying classroom activities and have both implemented these techniques but, in this session, Katrina did most of the presenting and I presented the collaborative assessment task examples, with some facilitation.

The trick here is, of course, to find examples that are both effective as teaching tools and are effective as examples. The approach I chose to take was to remind everyone in the room of what the most important aspects were to making this work with students and I did this by deliberately starting with a bad example. This can be a difficult road to walk because, when presenting a bad example, you need to convince everyone that your choice was deliberate and that you actually didn’t just stuff things up.

My approach was fairly simple. Break people into groups, based on where they were currently sitting, and then I immediately went into the question, which had been tailored for the crowd and for my purposes:

“I want you to talk about the 10 things that you’re going to do in the next 5 years to make progress in your career and improve your job performance.”

And why not? Everyone in the room was interested in education and, most likely, had a job at a time when it’s highly competitive and hard to find or retain work – so everyone has probably thought about this. It’s a fair question for this crowd.

Well, it would be, if it wasn’t so anxiety inducing. Katrina and I both observed a sea of frozen faces as we asked a question that put a large number of participants on the spot. And the reason I did this was to remind everyone that anxiety impairs genuine participation and willingness to engage. There were a large number of frozen grins with darting eyes, some nervous mumbles and a whole lot of purposeless noise, with the few people who were actually primed to answer that question starting to lead off.

I then stopped the discussion immediately. “What was wrong with that?” I asked the group.

Well, where do we start? Firstly, it’s an individual activity, not a collaborative activity – there’s no incentive or requirement for discussion, groupwork or anything like that. Secondly, while we might expect people to be able to answer this, it is a highly charged and personal areas, and you may not feel comfortable discussing your five year plan with people that you don’t know. Thirdly, some people know that they should be able to answer this (or at least some supervisors will expect that they can) but they have no real answer and their anxiety will not only limit their participation but it will probably stop them from listening at all while they sweat their turn. Finally, there is no point to this activity – why are we doing this? What are we producing? What is the end point?

My approach to collaborative activity is pretty simple and you can read any amount of Perry, Dickinson, Hamer et al (and now us as well) to look at relevant areas and Contributing Student Pedagogy, where students have a reason to collaborate and we manage their developmental maturity and their roles in the activity to get them really engaged. Everyone can have difficulties with authority and recognising whether someone is making enough contribution to a discussion to be worth their time – this is not limited to students. People, therefore, have to believe that the group they are in is of some benefit to them.

So we stepped back. I asked everyone to introduce themselves, where they came from and give a fact about their current home that people might not know. Simple task, everyone can do it and the purpose was to tell your group something interesting about your home – clear purpose, as well. This activity launched immediately and was going so well that, when I tried to move it on because the sound levels were dropping (generally a good sign that we’re reaching a transition), some groups asked if they could keep going as they weren’t quite finished. (Monitoring groups spread over a large space can be tricky but, where the activity is working, people will happily let you know when they need more time.) I was able to completely stop the first activity and nobody wanted me to continue. The second one, where people felt that they could participate and wanted to say something, needed to keep going.

Having now put some faces to names, we then moved to a simple exercise of sharing an interesting teaching approach that you’d tried recently or seen at the conference and it’s important to note the different comfort levels we can accommodate with this – we are sharing knowledge but we give participants the opportunity to share something of themselves or something that interest them, without the burden of ownership. Everyone had already discovered that everyone in the group had some areas of knowledge, albeit small, that taught them something new. We had started to build a group where participants valued each other’s contribution.

I carried out some roaming facilitation where I said very little, unless it was needed. I sat down with some groups, said ‘hi’ and then just sat back while they talked. I occasionally gave some nodded or attentive feedback to people who looked like they wanted to speak and this often cued them into the discussion. Facilitation doesn’t have to be intrusive and I’m a much bigger fan of inclusiveness, where everyone gets a turn but we do it through non-verbal encouragement (where that’s possible, different techniques are required in a mixed-ability group) to stay out of the main corridor of communication and reduce confrontation. However, by setting up the requirement that everyone share and by providing a task that everyone could participate in, my need to prod was greatly reduced and the groups mostly ran themselves, with the roles shifting around as different people made different points.

We covered a lot of the underlying theory in the talk itself, to discuss why people have difficulty accepting other views, to clarify why role management is a critical part of giving people a reason to get involved and something to do in the conversation. The notion that a valid discursive role is that of the supporter, to reinforce ideas from the proposer, allows someone to develop their confidence and critically assess the idea, without the burden of having to provide a complex criticism straight away.

At the end, I asked for a show of hands. Who had met someone knew? Everyone. Who had found out something they didn’t know about other places? Everyone. Who had learned about a new teaching technique that they hadn’t known before. Everyone.

My one regret is that we didn’t do this sooner because the conversation was obviously continuing for some groups and our session was, sadly, on the last day. I don’t pretend to be the best at this but I can assure you that any capability I have in this kind of activity comes from understanding the theory, putting it into practice, trying it, trying it again, and reflecting on what did and didn’t work.

I sometimes come out of a lecture or a collaborative activity and I’m really not happy. It didn’t gel or I didn’t quite get the group going as I wanted it to – but this is where you have to be gentle on yourself because, if you’re planning to succeed and reflecting on the problems, then steady improvement is completely possible and you can get more comfortable with passing your room control over to the groups, while you move to the facilitation role. The more you do it, the more you realise that training your students in role fluidity also assists them in understanding when you have to be in control of the room. I regularly pass control back and forward and it took me a long time to really feel that I wasn’t losing my grip. It’s a practice thing.

It was a lot of fun to give the session and we spent some time crafting the ‘bad example’, but let me summarise what the good activities should really look like. They must be collaborative, inclusive, achievable and obviously beneficial. Like all good guidelines there are times and places where you would change this set of characteristics, but you have to know your group well to know what challenges they can tolerate. If your students are more mature, then you push out into open-ended tasks which are far harder to make progress in – but this would be completely inappropriate for first years. Even in later years, being able to make some progress is more likely to keep the group going than a brick wall that stops you at step 1. But, let’s face it, your students need to know that working in that group is not only not to their detriment, but it’s beneficial. And the more you do this, the better their groupwork and collaboration will get – and that’s a big overall positive for the graduates of the future.

To everyone who attended the session, thank you for the generosity and enthusiasm of your participation and I’m catching up on my business cards in the next weeks. If I promised you an e-mail, it will be coming shortly.

A Brief Aside On Blogging

Posted: March 24, 2013 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, blogging, community, education, higher education, reflection Leave a commentI ran into someone last night was a reader of my blog (Hi, Maria) and, as always, it was slightly strange to run into someone who had been reading my rantings for over a year before finally meeting me in the flesh. Although I always get very self-conscious when it happens, the real benefit is the reminder that it is not just spam bots and ad robots that are reading my feed – there are real readers out there beyond the small group who are commenting (and thank you for your comments!).

As you can see, I was reminded to start blogging again after a long silence and the occasional post. Now I am writing – two posts in one day!. Interesting – it seems that appreciation of worth provides motivation…

Who would have thought it?