Time Banking and Plagiarism: Does “Soul Destroying” Have An Ethical Interpretation?

Posted: June 25, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, design, education, educational problem, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, learning, plagiarism, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, time banking, tools, work/life balance, workload 4 CommentsYesterday, I wrote a post on the 40 hour week, to give an industrial basis for the notion of time banking, and I talked about the impact of overwork. One of the things I said was:

The crunch is a common feature in many software production facilities and the ability to work such back-breaking and soul-destroying shifts is often seen as a badge of honour or mark of toughness. (Emphasis mine.)

Back-breaking is me being rather overly emphatic regarding the impact of work, although in manual industries workplace accidents caused by fatigue and overwork can and do break backs – and worse – on a regular basis.

But soul-destroying? Am I just saying that someone will perform their tasks as an automaton or zombie, or am I saying something more about the benefit of full cognitive function – the soul as an amalgam of empathy, conscience, consideration and social factors? Well, the answer is that, when I wrote it, I was talking about mindlessness and the removal of the ability to take joy in work, which is on the zombie scale, but as I’ve reflected on the readings more, I am now convinced that there is an ethical dimension to fatigue-related cognitive impairment that is important to talk about. Basically, the more tired you get, the more likely you are to function on the task itself and this can have some serious professional and ethical considerations. I’ll provide a basis for this throughout the rest of this post.

The paper I was discussing, on why Crunch Mode doesn’t work, listed many examples from industry and one very interesting paper from the military. The paper, which had a broken link in the Crunch mode paper, may be found here and is called “Sleep, Sleep Deprivation, and Human Performance in Continuous Operations” by Colonel Gregory Belenky. Now, for those who don’t know, in 1997 I was a commissioned Captain in the Royal Australian Armoured Corps (Reserve), on detachment to the Training Group to set up and pretty much implement a new form of Officer Training for Army Reserve officers in South Australia. Officer training is a very arduous process and places candidates, the few who make it in, under a lot of stress and does so quite deliberately. We have to have some idea that, if terrible things happen and we have to deploy a human being to a war zone, they have at least some chance of being able to function. I had been briefed on most of the issues discussed in Colonel Belenky’s paper but it was only recently that I read through the whole thing.

And, to me today as an educator (I resigned my commission years ago), there are still some very important lessons, guidelines and warnings for all of us involved in the education sector. So stay with me while I discuss some of Belenky’s terminology and background. The first term I want to introduce is droning: the loss of cognitive ability through lack of useful sleep. As Belenky puts in, in the context of US Army Ranger training:

…the candidates can put one foot in front of another and respond if challenged, but have difficulty grasping their situation or acting on their own initiative.

What was most interesting, and may surprise people who have never served with the military, is that the higher the rank, the less sleep people got – and the higher level the formation, the less sleep people got. A Brigadier in charge of a Brigade is going to, on average, get less sleep than the more junior officers in the Brigade and a lot less sleep than a private soldier in a squad. As an officer, my soldiers were fed before me, rested before me and a large part of my day-to-day concern was making sure that they were kept functioning. This keeps on going up the chain and, as you go further up, things get more complex. Sadly, the people shouldering the most complex cognitive functions with the most impact on the overall battlefield are also the people getting the least fuel for their continued cognitive endeavours. They are the most likely to be droning: going about their work in an uninspired way and not really understanding their situation. So here is more evidence from yet another place: lack of sleep and fatigue lead to bad outcomes.

One of the key issues Belenky talks about is the loss of situational awareness caused by the accumulated sleep debt, fatigue and overwork suffered by military personnel. He gives an example of an Artillery Fire Direction Centre – this is where requests for fire support (big guns firing large shells at locations some distance away) come to and the human plotters take your requests, transform them into instructions that can be given to the gunners and then firing starts. Let me give you a (to me) chilling extract from the report, which the Crunch Mode paper also quoted:

Throughout the 36 hours, their ability to accurately derive range, bearing, elevation, and charge was unimpaired. However, after circa 24 hours they stopped keeping up their situation map and stopped computing their pre-planned targets immediately upon receipt. They lost situational awareness; they lost their grasp of their place in the operation. They no longer knew where they were relative to friendly and enemy units. They no longer knew what they were firing at. Early in the simulation, when we called for simulated fire on a hospital, etc., the team would check the situation map, appreciate the nature of the target, and refuse the request. Later on in the simulation, without a current situation map, they would fire without hesitation regardless of the nature of the target. (All emphasis mine.)

Here, perhaps, is the first inkling of what I realised I meant by soul destroying. Yes, these soldiers are overworked to the point of droning and are now shuffling towards zombiedom. But, worse, they have no real idea of their place in the world and, perhaps most frighteningly, despite knowing that accidents happen when fire missions are requested and having direct experience of rejecting what would have resulted in accidental hospital strikes, these soldiers have moved to a point of function where the only thing that matters is doing the work and calling the task done. This is an ethical aspect because, from their previous actions, it is quite obvious that there was both a professional and ethical dimension to their job as the custodians of this incredibly destructive weaponry – deprive them of enough sleep and they calculate and fire, no longer having the cognitive ability (or perhaps the will) to be ethical in their delivery. (I realise a number of you will have choked on your coffee slightly at the discussion of military ethics but, in the majority of cases, modern military units have a strong ethical code, even to the point of providing a means for soldiers to refuse to obey illegal orders. Most failures of this system in the military can be traced to failures in a unit’s ethical climate or to undetected instability in the soldiers: much as in the rest of the world.)

The message, once again, is clear. Overwork, fatigue and sleeplessness reduce the ability to perform as you should. Belenky even notes that the ability to benefit from training quite clearly deteriorates as the fatigue levels increase. Work someone hard enough, or let them work themselves hard enough, and not only aren’t they productive, they can’t learn to do anything else.

The notion of situational awareness is important because it’s a measure of your sense of place, in an organisational sense, in a geographical sense, in a relative sense to the people around you and also in a social sense. Get tired enough and you might swear in front of your grandma because your social situational awareness is off. But it’s not just fatigue over time that can do this: overloading someone with enough complex tasks can stress cognitive ability to the point where similar losses of situational awareness can occur.

Helmet fire is a vivid description of what happens when you have too many tasks to do, under highly stressful situations, and you lose your situational awareness. If you are a military pilot flying on instruments alone, especially with low or zero visibility, then you have to follow a set of procedures, while regularly checking the instruments, in order to keep the plane flying correctly. If the number of tasks that you have to carry out gets too high, and you are facing the stress of effectively flying the plane visually blind, then your cognitive load limits will be exceeded and you are now experiencing helmet fire. You are now very unlikely to be making any competent contributions at all at this stage but, worse, you may lose your sense of what you were doing, where you are, what your intentions are, which other aircraft are around you: in other words, you lose situational awareness. At this point, you are now at a greatly increased risk of catastrophic accident.

To summarise, if someone gets tired, stressed or overworked enough, whether acutely or over time, their performance goes downhill, they lose their sense of place and they can’t learn. But what does this have to do with our students?

A while ago I posted thoughts on a triage system for plagiarists – allocating our resources to those students we have the most chance of bringing back to legitimate activity. I identified the three groups as: sloppy (unintentional) plagiarism, deliberate (but desperate and opportunistic) plagiarism and systematic cheating. I think that, from the framework above, we can now see exactly where the majority of my ‘opportunistic’ plagiarists are coming from: sleep-deprived, fatigued and (by their own hands or not) over-worked students losing their sense of place within the course and becoming focused only on the outcome. Here, the sense of place is not just geographical, it is their role in the social and formal contracts that they have entered into with lecturers, other students and their institution. Their place in the agreements for ethical behaviour in terms of doing the work yourself and submitting only that.

If professional soldiers who have received very large amounts of training can forget where there own forces are, sometimes to the tragic extent that they fire upon and destroy them, or become so cognitively impaired that they carry out the mission, and only the mission, with little of their usual professionalism or ethical concern, then it is easy to see how a student can become so task focussed that start to think about only ending the task, by any means, to reduce the cognitive load and to allow themselves to get the sleep that their body desperately needs.

As always, this does not excuse their actions if they resort to plagiarism and cheating – it explains them. It also provides yet more incentive for us to try and find ways to reach our students and help them form systems for planning and time management that brings them closer to the 40 hour ideal, that reduces the all-nighters and the caffeine binges, and that allows them to maintain full cognitive function as ethical, knowledgable and professional skill practitioners.

If we want our students to learn, it appears that (for at least some of them) we first have to help them to marshall their resources more wisely and keep their awareness of exactly where they are, what they are doing and, in a very meaningful sense, who they are.

Time Banking: Aiming for the 40 hour week.

Posted: June 24, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, educational problem, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, MIKE, principles of design, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, time banking, tools, universal principles of design, work/life balance 5 CommentsI was reading an article on metafilter on the perception of future leisure from earlier last century and one of the commenters linked to a great article on “Why Crunch Mode Doesn’t Work: Six Lessons” via the International Game Designers Association. This article was partially in response to the quality of life discussions that ensued after ea_spouse outed the lifestyle (LiveJournal link) caused by her spouse’s ludicrous hours working for Electronic Arts, a game company. One of the key quotes from ea_spouse was this:

Now, it seems, is the “real” crunch, the one that the producers of this title so wisely prepared their team for by running them into the ground ahead of time. The current mandatory hours are 9am to 10pm — seven days a week — with the occasional Saturday evening off for good behavior (at 6:30pm). This averages out to an eighty-five hour work week. Complaints that these once more extended hours combined with the team’s existing fatigue would result in a greater number of mistakes made and an even greater amount of wasted energy were ignored.

This is an incredible workload and, as Evan Robinson notes in the “Crunch Mode” article, this is not only incredible but it’s downright stupid because every serious investigation into the effect of working more than 40 hours a week, for extended periods, and for reducing sleep and accumulating sleep deficit has come to the same conclusion: hours worked after a certain point are not just worthless, they reduce worth from hours already worked.

Robinsons cites studies and practices coming from industrialists as Henry Ford, who reduced shift length to a 40-hour work week in 1926, attracting huge criticism, because 12 years of research had shown that the shorter work week meant more output, not less. These studies have been going on since the 18th century and well into the 60’s at least and they all show the same thing: working eight hours a day, five days a week gives you more productivity because you get fewer mistakes, you get less fatigue accumulation and you have workers that are producing during their optimal production times (first 4-6 hours of work) without sliding into their negatively productive zones.

As Robinson notes, the games industry doesn’t seem to have got the memo. The crunch is a common feature in many software production facilities and the ability to work such back-breaking and soul-destroying shifts is often seen as a badge of honour or mark of toughness. The fact that you can get fired for having the audacity to try and work otherwise also helps a great deal in motivating people to adopt the strategy.

Why spend so many hours in the office? Remember when I said that it’s sometimes hard for people to see what I’m doing because, when I’m thinking or planning, I can look like I’m sitting in the office doing nothing? Imagine what it looks like if, two weeks before a big deadline, someone walks into the office at 5:30pm and everyone’s gone home. What does this look like? Because of our conditioning, which I’ll talk about shortly, it looks like we’ve all decided to put our lives before the work – it looks like less than total commitment.

As a manager, if you can tell everyone above you that you have people at their desks 80+ hours a week and will have for the next three months, then you’re saying that “this work is important and we can’t do any more.” The fact that people were probably only useful for the first 6 hours of every day, and even then only for the first couple of months, doesn’t matter because it’s hard to see what someone is doing if all you focus on is the output. Those 80+ hour weeks are probably only now necessary because everyone is so tired, so overworked and so cognitively impaired, that they are taking 4 times as long to achieve anything.

Yes, that’s right. All the evidence says that more than 2 months of overtime and you would have been better off staying at 40 hours/week in terms of measurable output and quality of productivity.

Robinson lists six lessons, which I’ll summarise here because I want to talk about it terms of students and why forward planning for assignments is good practice for better smoothing of time management in the future. Here are the six lessons:

- Productivity varies over the course of the workday, with greatest productivity in the first 4-6 hours. After enough hours, you become unproductive and, eventually, destructive in terms of your output.

- Productivity is hard to quantify for knowledge workers.

- Five day weeks of eight house days maximise long-term output in every industry that has been studied in the past century.

- At 60 hours per week, the loss of productivity caused by working longer hours overwhelms the extra hours worked within a couple of months.

- Continuous work reduces cognitive function 25% for every 24 hours. Multiple consecutive overnighters have a severe cumulative effect.

- Error rates climb with hours worked and especially with loss of sleep.

My students have approximately 40 hours of assigned work a week, consisting of contact time and assignments, but many of them never really think about that. Most plan in other things around their ‘free time’ (they may need to work, they may play in a band, they may be looking after families or they may have an active social life) and they fit the assignment work and other study into the gaps that are left. Immediately, they will be over the 40 hour marker for work. If they have a part-time job, the three months of one of my semesters will, if not managed correctly, give them a lumpy time schedule alternating between some work and far too much work.

Many of my students don’t know how they are spending their time. They switch on the computer, look at the assignment, Skype, browse, try something, compile, walk away, grab a bite, web surf, try something else – wow, three hours of programming! This assignment is really hard! That’s not all of them but it’s enough of them that we spend time on process awareness: working out what you do so you know how to improve it.

Many of my students see sports drinks, energy drinks and caffeine as a licence to not sleep. It doesn’t work long term as most of us know, for exactly the reasons that long term overwork and sleeplessness don’t work. Stimulants can keep you awake but you will still be carrying most if not all of your cognitive impairment.

Finally, and most importantly, enough of my students don’t realise that everything I’ve said up until now means that they are trying to sit my course with half a brain after about the halfway point, if not sooner if they didn’t rest much between semesters.

I’ve talked about the theoretical basis for time banking and the pedagogical basis for time banking: this is the industrial basis for time banking. One day I hope that at least some of my students will be running parts of their industries and that we have taught them enough about sensible time management and work/life balance that, as people in control of a company, they look at real measures of productivity, they look at all of the masses of data supporting sensible ongoing work rates and that they champion and adopt these practices.

As Robinson says towards the end of the article:

Managers decide to crunch because they want to be able to tell their bosses “I did everything I could.” They crunch because they value the butts in the chairs more than the brains creating games. They crunch because they haven’t really thought about the job being done or the people doing it. They crunch because they have learned only the importance of appearing to do their best to instead of really of doing their best. And they crunch because, back when they were programmers or artists or testers or assistant producers or associate producers, that was the way they were taught to get things done. (Emphasis mine.)

If my students can see all of their requirements ahead of time, know what is expected, have been given enough process awareness, and have the will and the skill to undertake the activities, then we can potentially teach them a better way to get things done if we focus on time management in a self-regulated framework, rather than imposed deadlines in a rigid authority-based framework. Of course, I still have a lot of work to to demonstrate that this will work but, from industrial experience, we have yet another very good reason to try.

Time Banking: Foresightedness and Reward

Posted: June 23, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, higher education, learning, teaching, time banking, work/life balance, workload 2 CommentsYou may have noticed that I’ve stopped numbering the time banking posts – you may not have noticed that they were numbered in the first place! The reason is fairly simple and revolves around the fact that the numbers are actually meaningless. It’s not as if I have a huge plan of final sequence of the time banking posts. I do have a general idea but the order can change as one idea or another takes me and I feel that numbering them makes it look as if there is some grand sequence.

There isn’t. That’s why they all tend to have subtitles after them so that they can be identified and classified in a cognitive sequence. So, why am I telling you this? I’m telling you this so that you don’t expect “Time Banking 13” to be something special, or (please, no) “Time Banking 100” to herald the apocalypse.

The Druids invented time banking but could never find a sufficiently good Oracle to make it work. The Greeks had the Oracle but not the bank. This is why the Romans conquered everywhere. True story!

If I’m going to require students to self-regulate then, whether through operant or phenomenological mechanisms, the outcomes that they receive are going to have to be shaped to guide the student towards a self-regulating model. In simple terms, they should never feel that they have wasted their time, that they are under-appreciated or that they have been stupid to follow a certain path.

In particular, if we’re looking at time management, then we have to ensure that time spent in advance is never considered to be wasted time. What does that mean to me as a teacher, if I set an assignment in advance and students put work towards it – I can’t change the assignment arbitrarily. This is one of the core design considerations for time banking: if deadlines are seen as arbitrary (and extending them in case of power failures or class-wide lack of submission can show how arbitrary they are) then we allow the students to make movement around the original deadlines, in a way that gives them control without giving us too much extra work. If I want my students to commit to planning ahead and doing work before the due date then some heavy requirements fall on me:

- I have to provide the assignment work ahead of schedule and, preferably, for the entire course at the start of the semester.

- The assignments stay the same throughout that time. No last minute changes or substitutions.

- The oracle is tied to the assignment and is equally reliable.

This requires a great deal of forward planning and testing but, more importantly, it requires a commitment from me. If I am asking my students to commit, I have to commit my time and planning and attention to detail to my students. It’s that simple. Nobody likes to feel like a schmuck. Like they invested time under false pretences. That they had worked on what they thought was a commitment but it turned out that someone just hadn’t really thought things through.

Wasting time and effort discourages people. It makes people disengage. It makes them less trustful of you as an educator. It makes them less likely to trust you in the future. It reduces their desire to participate. This is the antithesis of what I’m after with increasing self-regulation and motivation to achieve this, which I label under the banner of my ‘time banking’ project.

But, of course, it’s not as if we’re not already labouring under this commitment to our students, at least implicitly. If we don’t follow the three requirements above then, at some stage, students will waste effort and, believe me, they’re going to question what they’re doing, why they’re bothering, and some of them will drop out, drift away and be lost to us forever. Never thinking that you’ve wasted your time, never feeling like a schmuck, seeing your ideas realised, achieving goals: that’s how we reward students, that’s what can motivate students and that’s how we can move the on to higher levels of function and achievement.

Speaking of measurement

Posted: June 19, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: blogging, education, measurement, MIKE, reflection, thinking, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentIn a delightfully serendipitous alignment of the planets, today marks my 200th post and my 10,000th view. Given that posting something new every day, which strives if not succeeds at being useful and interesting, is sometimes a very demanding commitment, the knowledge that people are reading does help me to keep it going. However, it’s the comments, both here and on FB, that show that people can sometimes actually make use of what I’m talking about that is the real motivator for me.

via http://10000.brisseaux.com/ (This looked smaller in preview but I really liked its solidity so didn’t want to scale it)

Thank you, everyone, for your continued reading and support, and to everyone else out there blogging who is showing me how it can be done better (and there are a lot of people who are doing it much better than I am).

Have a great day, wherever you are!

Personal Reflection on Time Management: Why I Am a Bad Role Model.

Posted: June 15, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, education, higher education, measurement, mythical man month, reflection, resources, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, workload 2 CommentsDo any of you remember that scene from “Pretty Woman”, when Richard Gere’s character Edward asks his ex-girlfriend Susan if she had spent more time talking to his secretary than to him? Her reply was, simply, “she was one of my bridesmaids”. Any time in a relationship of any kind that you don’t meet the needs of the people in the relationship, it’s going to cause problems. (Not all problems have to end with you scaling a ladder to patch up your relationship with Julia Roberts but there will be problems.) Now, before anyone is wondering (or my friends are worried), my marriage is still great, I’m talking about my professional relationship with my students.

While I’ve been critical of myself and my teaching this semester, where I’ve done a good job but not necessarily excelled across the board, I haven’t identified one of the greatest problems that has crept in – no-one in their right mind should be emulating what I laughingly refer to as my work ethic, time commitment or current pursuit of success. Right now, I am not a good role model for students. While I am still ethical, professional, knowledgable and I’m apparently doing a good job, I cannot present myself as a role model to my students because I am losing the time that I need to seize new opportunities, and to allow for the unrushed catch-up time with other people that is vital to doing a job such as mine and doing it well. At the moment, any student who comes to see me does so knowing that I will have 15-30 minutes, tops, and that I will then have to rush off, elsewhere, to go and do something else. It doesn’t matter when they come to see me – if I’m in at 7:30am it’s because the day is starting at 8. If I’m still there at 7pm at night it’s because I have to be in order to meet requirements for that day or the next. Let me give you an example from my lectures.

My Student Experience of Learning and Teaching results have come in and there have been a lot of warm and rewarding comments from my students, among a pleasing overall rating. But one of my students hit the nail on the head. “[Nick] always seems to have a lot to say and constantly looks at his watch. (I assume that it’s to keep within time constraints) the problem is that he feels like he’s rushing.”

Ouch. That’s far too true and, while only one student noted it, you bet every other student was watching me use my watch to check my time progress through a busy, informative but ultimately time constrained lecture and at least some of them thought “Hmm, I have a question but I don’t want to bother him.”

It’s my job to be bothered! It’s my job to answer questions! Right now, it’s pretty obvious that students are getting the vibe that I’m a good lecturer, I care about them, I’m working well to give them the right knowledge and they love the course that I built… but… they don’t want to bother me because I’m too busy. Because I look too busy.

Every student who comes to see does so in the one of the windows that I have in my day, often between meetings, my meetings back up on each other with monotonous regularity and, looking at my calendar for last, week, the total amount of time that was uncommitted prior to the week starting was…

75 minutes.

Including the fact that Tuesday started at 7:30am and went until 6:15pm.

Please believe me when I say that I’m not boasting – I’m not proud of this, I think it’s the sign of poor scheduling and workaholism. This should be read as what it is, a sign that I have let my responsibilities pile up in a way that means that I am running the risk of becoming a stereotypically “grumpy old Professor”, who is too busy to see students.

So when you read all of this stuff about Time Banking and think “Well, I guess I can see some of his point – for assignments…” I’m trying to work out how I can take the primary goal of time banking – to make people think about their time commitments in a way that allows them to approximate a manageable uniformity of effort across time to achieve good results – and to work out how I can think about my own time in the same way. How do I adjust my boundaries in time and renegotiate while providing my own oracle and incentives for change? If I can crack that, then solving the student problem should have been made much easier.

How do I become the kind of person that I would want my students to be? Right now, it requires me to think about my commitments and my time, to treat my time as a scarce and precious commodity, but in a way that allows me to do all of the things I need to do in my job and all of the things that I love to do in my job, yet still have the time to sit around, grab a slow coffee, make a lunch booking with someone with less than a month’s notice and to get my breathing room back.

I have one of the best jobs in the world but the way I’m doing it is probably unsustainable and it’s not really in the spirit of the job that I want to do. It’s more than just me, too. I need to be seen to be approachable and to do that I have to actually be approachable, which means finding a way that makes me worthy of being a good overall role model again.

Learning from other people – Academic Summer Camp (except in winter???)

Posted: June 3, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: data visualisation, education, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, R, reflection, resources, summer camp, text analysis, tools, universal principles of design, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentI’ve just signed up for the Digital Humanities Winter Institute course on “Large-scale text analysis with R”. K read about it on ProfHacker and passed it on to me thinking I’d be interested. Of course, I was, but it goes well beyond learning R itself. R is a statistically focused programming package that is available for free for most platforms. It’s the statistical (and free, did I mention that?) cousin to the mathematically inclined Matlab.

I’ve spoken about R before and I’ve done a bit of work in it but, and here’s why I’m going, I’ve done all of it from within a heavily quantitative Computer Science framework. What excites me about this course is that I will be working with people from a completely different spectrum and with a set of text analyses with which I’m not very familiar at all. Let me post the text of the course here (from this website) [my bold]:

Large-Scale Text Analysis with R

Instructor: Matt Jockers, Assistant Professor of Digital Humanities, Department of English, University of Nebraska, LincolnText collections such as the HathiTrust Digital Library and Google Books have provided scholars in many fields with convenient access to their materials in digital form, but text analysis at the scale of millions or billions of words still requires the use of tools and methods that may initially seem complex or esoteric to researchers in the humanities. Large-Scale Text Analysis with R will provide a practical introduction to a range of text analysis tools and methods. The course will include units on data extraction, stylistic analysis, authorship attribution, genre detection, gender detection, unsupervised clustering, supervised classification, topic modeling, and sentiment analysis. The main computing environment for the course will be R, “the open source programming language and software environment for statistical computing and graphics.” While no programming experience is required, students should have basic computer skills and be familiar with their computer’s file system and comfortable with the command line. The course will cover best practices in data gathering and preparation, as well as addressing some of the theoretical questions that arise when employing a quantitative methodology for the study of literature. Participants will be given a “sample corpus” to use in class exercises, but some class time will be available for independent work and participants are encouraged to bring their own text corpora and research questions so they may apply their newly learned skills to projects of their own.

There are two things I like about this: firstly that I will be exposed to such a different type and approach to analysis that is going to be immediately useful in the corpus analyses that we’re planning to carry out on our own corpora, but, secondly, because I will have an intensive dedicated block of time in which to pursue it. January is often a time to take leave (as it’s Summer in Australia) – instead, I’ll be rugged up in the Maryland chill, sitting with like-minded people and indulging myself in data analysis and learning, learning, learning, to bring knowledge home for my own students and my research group.

So, this is my Summer Camp. My time to really indulge myself in my coding and just hack away at analyses and see what happens.

I’ve also signed up to a group who are going to work on the “Million Syllabi Project Hack-a-thon“, where “we explore new ways of using the million syllabi dataset gathered by Dan Cohen’s Syllabus Finder Tool” (from the web site). 10 years worth of syllabi to explore, at a time when my school is looking for ways to be able to teach into more areas, to meet more needs, to create a clear and attractive identity for our discipline? A community of hackers looking at ways of recomposing, reinterpreting and understanding what is in this corpus?

How can I not go? I hope to see some of you there! I’ll be the one who sounds Australian and shivers a lot.

Rush, Rush: Baby, Please Plan To Submit Your Work Earlier Than The Last Minute

Posted: May 29, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, context, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, higher education, measurement, MIKE, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, work/life balance, workload 4 CommentsSorry, Paula Abdul, but I had to steal a song lyric from you.

AND MANGLE IT!

This is the one of the first pictures that comes up when you search for ‘angry Paula Abdul”. Sorry, Lamar.

I’ve been marking the first “process awareness” written report from my first-year students. A one-page PDF that shows their reflections on their timeliness and assignment performance to date and how they think that they can improve it or maintain it. There have been lots of interesting results from this. From about 100 students, I’ve seen many reports along the lines of “I planned, I assigned time, SO WHY DIDN’T I FOLLOW THE PLAN?” or “Wow, I never realised how much I needed a design until I was stuck in the middle of a four-deep connection of dynamic arrays.”

This is great – understanding why you are succeeding or failing allows you to keep doing the things that work, and change the things that don’t. Before this first-year curriculum restructure, and this course, software development process awareness could avoid our students until late second- or third-year. Not any more. You got run over by the infamous Library prac? You know, you should have written a design first. And now my students have all come to this realisation as well. Two of my favourite quotes so far are:

“[Programming in C++] isn’t hard but it’s tricky.”

and

“It’s not until you have a full design [that you can] see the real scope of the project.”

But you know I’m all about measurement so, after I’d marked everything, I went back and looked at the scores, and the running averages. Now here’s the thing. The assignment was marked out of 10. Up until 2 hours before the due date, the overall average was about 8.3. For the last two hours, the average dropped to 7.2. The people commenting in the last two hours were making loose statements about handing up late, and not prioritising properly, but giving me enough that I could give them some marks. (It’s not worth a lot of marks but I do give marks for style and reflection, to encourage the activity.) The average mark is about 8/10 usually. So, having analysed this, I gave the students some general feedback, in addition to the personalised feedback I put on every assignment, and then told them about that divide.

The fact that the people before the last minute had the marks above the average, and that the people at the last minute had the marks below.

One of the great things about a reflection assignment like this is that I know that people are thinking about the specific problem because I’ve asked them to think about it and rewarded them with marks to do so. So when I give them feedback in this context and say “Look – planned hand-in gets better marks on average than last-minute panic” there is a chance that this will get incorporated into the analysis and development of a better process, especially if I give firm guidelines on how to do this in general and personalised feedback. Contextualisation, scaffolding… all that good stuff.

There are, as always, no guarantees, but moving this awareness and learning point forward is something I’ve been working on for some time. In the next 10 days, the students have to write a follow-up report, detailing how they used the lessons they learnt, and the strategies that they discussed, to achieve better or more consistent results for the next three practicals. Having given them guidance and framing, I now get to see what they managed to apply. There’s a bit of a marking burden with this one, especially as the follow-up report is 4-5 pages long, but it’s worth it in terms of the exposure I get to the raw student thinking process.

Apart from anything else, let me point out that by assigning 2/10 for style, I appear to get reports at a level of quality where I rarely have to take marks away and they are almost all clear and easy to read, as well as spell-checked and grammatically correct. This is all good preparation and, I hope, a good foundation for their studies ahead.

What Did You Learn From Higher Education?

Posted: May 27, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, curriculum, education, educational problem, feedback, higher education, reflection, work/life balance 1 CommentToday has been games day at my house. We’ve played some Arkham Horror and Lords of Waterdeep, one collaborative and one highly competitive board game, and it has been a lot of fun. It’s been the standard group of Australians around the table. Eight people, six with PhDs, and two currently studying for them. (That is, of course, not a serious comment on standard. A lot of my friends, including my wife, are University trained and have post-graduate qualifications.)

I was wondering what to talk about today and, at breakfast this morning, my wife suggested that I ask our guests what they got from going to University – what they learnt? (We gave them lunch and dinner so it wasn’t too much of an imposition. 🙂 )

My wife’s answer to the question was that she learnt to keep going, keep putting effort into her work to get something good out of a course. My answer was that I learnt that it was never over, even at the end of a degree – that you could always do something new, something different, change career. (Yes, we’re similar but not quite the same.)

When I asked my friends, I got a variety of responses, because we’d been playing games for over 8 hours and we’d had wine with dinner. One said that he was still learning, but that he thought it was more about the process than the output. One said that she learnt how to drink and keep up with men (I suspect this wasn’t her most serious answer). Another said that, although it sounded cynical, he thought it was often better to be convincing than right. One, who I work with closely, said that truly horrific educators cannot spoil kids if the kids are really keen. One said that he learnt programming.

The last answer got laughs from around the table, as did many of the answers – as did the question. There are always going to be a range of answers to a question like this: a person’s reaction to this question, especially when I told them was going to publish it, is generally going to be framed self-consciously. However, all of them are using the skills that they learnt in Higher Education and all of them at least started PhD studies, even if they hadn’t completed them yet. There is no doubt, in this group, that the University if a useful thing, even if particular instances are not fantastic exemplars of that.

But it’s an interesting question. What did you learn from your foray into higher ed, if you’ve done it. What do you think of when you think of higher education? If you’re going there, what are you expecting to learn? If you’ve never had any direct exposure, what do you think that people learn when they’re there?

Heroes

Posted: May 7, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, alan turing, Arland D Williams, Arland Williams, bruno schulz, education, heroes, higher education, inspiring students, learning, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches, turing, work/life balance 1 CommentI know that I learn best when I’m inspired and engaged, so I regularly look for things around me that I can bring into the classroom that go beyond “program this” or “design that”. Our students are surrounded by the real world and, unfortunately, it’s easy to understand why they might be influenced by things that are less than inspirational. I don’t want to be negative, but there are so many examples of bad behaviour on the national and international stage that, sometimes, you really wonder why you bother.

So, today, I’m going to talk about four people. Regrettably, three of them some of you won’t be able to talk about because of personal convictions, political considerations or the ages of your class, but I hope that most of you will either have learned something new or remembered something important by the time I’m finished. Are these people actually heroes, given the title of my post? Well, one is a professional inspiration to me, one is an artistic inspiration to me (and reminder of the importance of what I’m doing), one is generally inspiring in the area of democracy and dedication, and the other… well, the other, I can barely look at his picture without wondering if I could ever approach the level of selflessness and heroism that he demonstrated. But I’ll talk about him last.

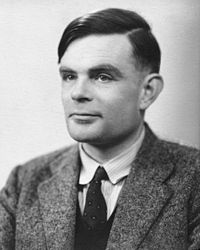

This is Alan Turing, the most likely candidate for the term “Father of Computer Science”. Witty, well-educated, highly intelligent and thoughtful, he was leader in cryptanalysis at Bletchley Park, providing statistical and mathematical genius to breaking codes including the design of the bombe, the machine that attacked Enigma. Importantly, for me as a Computer Scientist, he developed Turing Machines, effectively providing the foundations of studies in the theory of computation. He provided the first detailed design of a computer that used a stored program, very different from the electrical calculators of the day. He defined some of the key terms that we still use in Artificial Intelligence. (There’s so much more but it wouldn’t mean much to you outside the discipline, but he’s well worth looking up.)

Of course, some of you can’t mention Turing to your students, because he was a known homosexual, with a conviction for gross indecency in 1952 after admitting to a consensual homosexual relationship. He had a choice between imprisonment or chemical castration (he chose the latter) and his security clearance was revoked and he was barred from continuing with his security work. He was found dead in 1954, having (most likely) committed suicide.

There is no doubt that the field I am in is the better (or even exists) for Turing having lived and worked in this field. We are poorer for his early loss and, personally, I’m ashamed that persecution based on his sexual orientation may have led to the premature self-administered death of a genius.

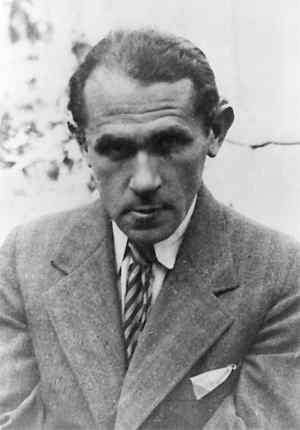

Meet Bruno Schulz, author, artist and critic. Schulz wrote some incredible works, contributed murals and was, despite his somewhat hermitic nature, an influential contributor to the arts. Schulz was born and lived, for most of his life, in Drohobych, Galicia. His contributions, although limited by his early death, include the highly influential works “Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass” and “The Street of Crocodiles”. In 1938, he was awarded the Polish Academy’s Golden Laurel award for his works and translations.

I am currently writing a series of stories that were inspired, in part, by the “Sanatorium” with its dreamlike qualities, stories interweaving with unreliable narration and innate and unexpected metamorphoses. Schulz is a fascinating counterpoint to Borges for me, woven with the immersion in Jewish culture I would expect from Singer, but with a different tone that comes from through, even in the English translations I have to read.

We have no more works from Schulz, not even the fragments of the book he was working on at the time of his death “The Messiah”. Why was Schulz killed? After the German invasion of the Soviet Union in the Second World War, Drohobych was occupied and, for a time, Schulz (who was Jewish) was protected by a Gestapo officer who admired his artistic work. Unfortunately, another Gestapo officer, a rival of the first, decided to kill this “personal Jew” and shot Schulz on the way home. You will excuse me for being confusing by referring to neither officer by name.

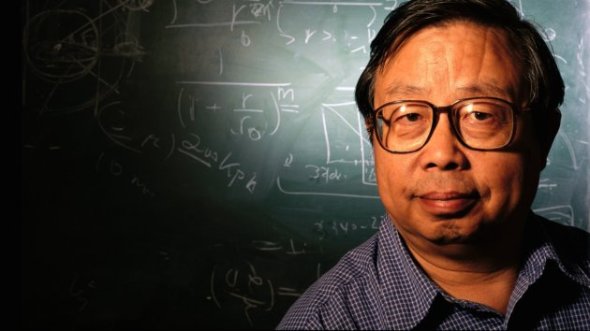

This person you may have heard of. Fang Lizhi died very recently, a Chinese Astrophysicist who lived in exile for over 22 years, after a life spent trying to pursue science despite being politically persona non grata and, for many years, not being able to publish under his own name. He survived hard labour during his re-education by the worker class during the cultural revolution but continued to fight against what he saw as severe obstacles to the pursuit of his scientific aims, including proscriptive ideological opposition to some of the key ideas required to be a successful astrophysicist or cosmologist.

In 1989, he was highly instrumental in the movement that occupied Tiananmen Square, despite not being directly involved in the protest and, once those protests had been dealt with, he decided that, with his wife, his safety was no longer ensured and he sought refuge at the US Embassy. He remained in the embassy for over a year, while diplomatic negotiations continued. Eventually he was allowed to leave and had an international career in his discipline, as well as speaking regularly on human rights and social responsibility. Of all the people on this list, Professor Fang died of old age, at 76, having managed to escape from the situation in which he found himself.

We talk a lot about academic freedom, or the entitlement to academic freedom, but we often forget that there is a harsh and heavy price imposed for it, depending upon the laws and the governments in which we find ourselves. That is a hard and heavy lesson.

Some of you will not be able to talk about Alan Turing, because he was gay. Some of you may have difficulty discussing Bruno Schulz, because of the involvement of Nazis or because he was a Jew. Some of you have may have stopped reading the moment you saw the picture of Fang Lizhi, because you didn’t want to get into trouble. Please keep reading.

So let me give you the story of the first man on this page. Let me tell you about a man who was a bank investigator. Recently divorced, with a youngest child of 17. I want to tell you about him because his story is the simplest and the most complex. He has no giant academic backstory, no grand contribution to literature, no oppression to fight. He just choose to be good.

In 1982, Arland D. Williams, Jr, was a passenger on board a plane from Washington DC to Florida, Air Florida Flight 90, that took off in freezing weather, iced up, failed to gain altitude and slammed into the 14th Street Bridge across the Potomac. The crash killed four motorists and the plane slid forward, down into the Potomac, with the tail breaking off as it did so. There were 79 people on board. Only 6 made it up and onto the tail, which was still floating.

When the rescue helicopter got there, they started recovering people from the tail section, dropping rescue ropes. Williams caught the rescue ropes multiple times and, instead of using them for himself, he handed them to the other passengers.

Life vests were dropped. Rescue balls. He handed them on.

The helicopter, overloaded and struggling with the conditions, got every other survivor back to shore, sometimes having to pick up the weak survivors multiple times. But Williams made sure that everyone else got helped before he did.

Sadly, tragically, by the time the helicopter came back for him, the tail section had shifted and sank, taking him with it. As it happened, Williams had made so little fuss about himself during his actions that his identity had to be determined after the fact.

It would be easy, and cynical, to describe human beings in terms of animals, given some of the awful things we do. Taking away a man’s livelihood (maybe even killing him) because of who he’s in love with? Killing someone because you have an argument with someone else? Persecuting someone for trying to pursue science or democracy?

Yet their stories survive, and we learn. Slowly, sometimes, but we learn.

It would be easy to assume that everyone, when desperate enough, would scrabble like rats to survive. (Except, of course, that not even rats do that. We just tell ourselves they do because we can’t sometimes recognise that this is just a paltry excuse for human evil.)

Here is your counter example – Arland Williams. Here is your existential proof that revokes the “WE ARE ALL LIKE THIS” Myth. There are so many more. Go back to the top of the page and look at that ordinary, middle-aged man. Look at someone who looked down at the freezing water around him and decided to do something great, something amazing, something heroic.

Making Time, Taking Time: 70, 10, 10, 10

Posted: March 29, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, higher education, measurement, mythical man month, principles of design, teaching approaches, work/life balance Leave a commentI just finished reading Katrina’s post on students who are scared to interrupt us because we look so busy and it made a lot of sense. It’s certainly something I’ve struggled with and anyone who has come into my office in the past few months has seen that I am really trying to give everyone as much time as possible – but I’m obviously balancing a lot of things.

I’ve been toying with some new models for setting up my time for the day and something I’m finding that works is 70/10/10/10 time. I can lose up to 70% of my day with pre-scheduled appointments, lectures, tutes, meetings and things like that, but the remaining 30% is broken down like this:

- 10% time reserved for the unforeseen – things like the opportunity to put a proposal in to attend an important meeting in California, that lobbed onto my desk yesterday and needed about 3 hours of work to get to fruition – completed by this Friday. I seem to get things like this every day!

- 10% time reserved for me to do things like go to the bathroom, eat lunch and enjoy a coffee. I need time to get from point A to point B – and sitting the whole day hungry, thirsty or … anything else will not produce my best work.

- 10% time, reserved in my head and on my calendar, for students who drop in to ask questions or who send me e-mail with questions (or post them on the forum). I should be making time. Yes, I have drop-in times normally but my students have a range of timetables and, after all, I am here to help. If I’m genuinely busy and out of time then I may have to use this time as well, but setting aside this time will help me to think about my students.

I look at the blog as an example. Every day, I put aside 20-30 minutes to write a post and, every day, I think of things that help me, or look for things to share, or go and do some research on CS Ed, or write up something interesting. (Some days I manage all of this!) Putting time aside for something gives you the mental ability to think “Yes, this is important and I should do this.”

Thanks, Katrina!