How Do We Equate Investment in On-Line Learning Versus Face-to-Face?

Posted: May 21, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: blended learning, design, education, educational problem, higher education, learning, measurement, on-line learning, teaching, teaching approaches, teaching equivalence unit Leave a commentIt’s relatively early/late where I am because my jet lag has hit and I’m not quite sure which zone I’m in. This is probably a little rambly but I hope that there’s at least something to drive some thinking or discussion. No doubt, there is an excellent link that I can’t find, which describes all of this, so please send it to me or drop it into the comments!

One of the things I’m thinking about at the moment is how to quantify an equivalent ‘Teaching Dollar’ that reflects what an institution has to spend to support a student. Now, while this used to be based on investment in a bricks-and-mortar campus, a set number of hours and instructional support, we now have an extra dimension as blended learning spreads – the costs required for on-line and mobile components. We can look at a course in terms of course content, number of units contributing to degree progress, hopefully tie this into a quantification of requisite skill and knowledge components and then get a very rough idea of what we’re spending per “knowledge progress unit” in board dollar terms.

What’s the electronic equivalent of a lecture theatre? If I can run an entire course on-line, for n students, should I get the equivalent dollar support value as if they were on campus, using the expensive bricks-and-mortar facilities? If we spend $x on lecture theatres, what do we have to spend on on-line resources to have the equivalent utility in terms of teaching support? In a flipped classroom, where almost all informational review takes place outside of class and class is reserved for face-to-face activities, we can increase the amount of material because it’s far more efficient for someone to read something than it is for us to chalk-and-talk them through it. Do we measure the time that we spent producing electronic materials in terms of how much classroom time we could have saved or do we just draw a line under it and say “Well, this is what we should have been doing?”

On-line initiatives don’t work unless they have enough support, instructor presence, follow-up and quality materials. There are implicit production costs, distribution issues – it all has to be built on a stable platform. To do this properly takes money and time, even if it’s sound investment that constructs a solid base for future expansion. Physical lecture theatres are, while extremely useful, expensive to build, slow to build and they can only be used by one class at a time. We’re still going to allocate an instructor to a course but, as we frequently discuss, some electronic aspects require a producer as well to allow the lecturer to stay focused on teaching (or facilitating learning) while the producer handles some of the other support aspects. Where does the money for that producer come from? The money you save by making better use of your physical resources or the money you save by being able to avoid building a new lecture theatre at all. If we can quantity an equivalent dollar value, somehow, then we can provide a sound case for the right levels of support for on-line and the investment in mobile and, rather than look like we’re spending more money, we may be able to work out if we’re spending more money or whether it’s just in a different form.

I’m mulling on a multi-axis model that identifies the investment in terms of physical infrastructure, production support and electronic resources. With the spread of PDF slides and lecture recordings, we’re already pushing along the electronic resources line but most of this is low investment in production support (and very few people get money for a slide producer). The physical infrastructure investment and use is high right now but it’s shifting. So what I’m looking to do is get some points in three-space that represent several courses and see if I can define a plane (or surface) that represents equivalence along the axes. I have a nasty suspicion that not all of the axes are even on the same scales – at least one of them feels log-based to me.

If we define a point in the space (x,y,z) as (Physical, Production, Electronic) then, assuming that a value of 10 corresponds to “everything in a lecture theatre” for physical (and the equivalent of total commitment on the other axes), then the “new traditional” lecture of physical lectures with slide support and recordings would be (10,0,2) and a high quality on-line course would be (0,10,10). Below is a very sketchy graph that conveys almost no information on this.

It would be really easy if x+y+z = V, where V was always the same magnitude, but the bounding equation is, on for a maximum value of M in each axis, actually x+y+z <= 3M. Could we even have a concept of negative contribution, to reflect that lack of use of a given facility will have an impact on learning and teaching investment in the rest of our course, or in terms of general awareness?

I suspect that I need a lot more thought and a lot more sleep on this. Come back in a few months. 🙂

Matters of Scale

Posted: May 20, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, captain jack harkness, captan jack, education, educational problem, higher education, learning, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches, torchwood, university 20XX, workload Leave a commentI wrote about how important it is to get people properly involved in new learning and teaching approaches – students and staff – based on the the whole condemnation, complaint, compliance and commitment model. But let me be absolutely clear as to why compliance is not enough.

Compliance doesn’t scale.

If you have a lot of people who are just doing what they’re told, but aren’t committed to it, then they’re not going to be willing explorers in the space. They’re not going to create new opportunities. Why? Because they don’t really believe in it, they’ve just reached the rather depressing stage of shuffling along, not complaining, just doing what they’re told. When we don’t explain to people, or we don’t manage to communicate, the importance of what we’re doing, then how can they commit to it?

I’m fortunate to be at a meeting full of people who have done amazing things. I’m really only here as a communicator of some great stuff going on at my Uni and in Australia, I’m a proxy for amazing things. But being around these people is really inspiring. They know why they’re doing it, they’ve heard all of the complaints, fought off the underminers and, in some cases, had to make some very hard calls to drive forward positive agendas for change. (Goodness, such phrases…) But they also know that they need other people to make it happen.

We need commitment, we need passion and we need people to scale up our solutions to the national and international level.

The Higher Educational world is changing – there’s no doubt about that. Some people look at things like Khan Academy and think “Oh no, the death of traditional education.” Most of the discussions I’ve had here, and I agree with this, are more along the lines of “Ok, how can we use this to go further?” Universities are all about knowledge and the development/discovery of more knowledge. If we have people out there with good on-line courses that cover the basics in disciplines, why not use them to allow us to go further? The gap between what I teach my undergraduates and what I do in my research is vast – just about anything I can do to get my students to develop skill and knowledge mastery is a good thing.

Ok, we are going to have to sort out quality issues, maybe certification or credit recording, work out if someone has done certain courses: there’s a lot of organisation to do here if we want to go down this path. But, most importantly, I don’t see this as the death of the University – I see this as an amazing opportunity to go further, do better things, allowing students and staff to get much, much more out of the educational system.

So everyone has learnt to program by the time that they’re 12? FANTASTIC! Now, we can start looking at actual Computer Science and putting trained algorithmicists out there along with extremely well-trained software engineers. We can finally start to really push out the boundaries of education and get people working smarter, sooner.

Are there risks and threats? Of course. But, no matter what happens, the University of the 21st Century is not the University of the previous millennium. Change is coming. Change is here. We may as well try to be as constructive as possible as we try to imagine the shape of the University of tomorrow. We’re not talking about University 2100, we’re talking 20XX, where XX is probably closer than many of us think.

To quote Captain Jack Harkness:

“The 21st century is when everything changes. And we have to be ready.”

Getting Into the Student’s Head: Representing the Student Perspective

Posted: May 16, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, education, higher education, in the student's head, learning, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, universal principles of design Leave a commentI’ve spent a lot of time on the road this year – sometimes talking about my own work, sometimes talking about that of a research group, sometimes talking about national initiatives in ICT and, quite often, trying to talk about how my students are reacting to all of this.

That’s hard because, to do that, I have to have a fairly good idea of how my students see what I’m doing, that they understand why I’m doing what I’m doing and I have to be honest with myself if I can’t get into their heads.

Apart from this kind of writing, I write a lot of fiction and this requires that you can get into someone else’s head so that you can write about their experience , allowing someone else to read about it. This is good practice for trying to understand students because it requires you to take that step back, make your head fit a different brain and be honest about how authentically you’re capturing that other perspective.

Of course, this is going to be hard to do with the ‘average’ student because, by many definitions, I’m not. I am one of the ones who passed their Bachelors, a Masters and then a PhD. Even making it through first year sets me apart from some of my students.

Rather than talk about my Uni, which most you wouldn’t know at all, I’ll talk about Stanford. Rough figures indicate that Stanford matriculates about 7000 undergraduates a year. They produce roughly 700 PhD students a year as well. So let’s assume (simplistically and inaccurately) that Stanford has a conversion rate of undergrad to PhD of 1 in 10 (I know, I know, transfers, but let’s ignore that.) (At the same time, 34,000 students apply to Stanford and only 2,400 get admitted – about 7%. We’ve already got some fiendish filtering going on.)

So someone who has graduated with a PhD and goes out to teach is, at most, similar in process and end point to 10% of the people who managed to get all the way through. And that’s the best case.

So whenever those of us who have PhDs and are teaching try to think of the student perspective, thinking of our own is not going to really help us, especially for first year, as it is those students who don’t think like us, who may not see our end point and who may not be at the right point yet, who need us to understand them the most.

Hurdles and Hang-ups: Identifying Those Things That Trip Up a Student

Posted: May 13, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: curriculum, design, education, educational problem, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, learning, measurement, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches 2 CommentsMost of the courses I teach have a number of guidelines in place that allow a student to, with relative ease and fairly early on, identify if they are meeting the requirements of the course. Some of these are based around their running assessment percentages, where a student knows their mark and can use this to estimate how they’re travelling. We use a minimum performance requirement that says that a student must achieve at least 40% in every component (where a component is “the examination” or “the aggregate mark across the whole of their programming assignments”) and 50% overall in order to pass. If a student doesn’t meet this, but would otherwise pass, we can look at targeted remedial (replacement) assessment in order to address the concern.

Bazinga! (With apologies to the Austrian athlete involved, who suffered no more injury than some cuts to his lower lip and jaw.)

One of the things we use is often referred to as a hurdle assessment, an assessment item that is compulsory and must be passed in order to pass the course. One of the good things about hurdle assessments is that you can take something that you consider to be a crucial skill and require a demonstration of adequate performance in that skill – well before the final examination and, often, in a way that is more practically oriented. Because of this we have practical programming exams early on in our course, to resolve the issues of students who can write about programming but can’t actually program yet.

It would be easy to think of these as barriers to progress, but the term hurdle is far more apt in this case, because if you visualise athletic training for the hurdles, you will see a sequence of hurdles leading to a goal. If you fall at one, then you require more training and then can attempt it again. This is another strong component of our guidelines – if we present hurdles, we must offer opportunities for learning and then reassessment.

Of course, this is the goal, role and burden of the educator: not the cheering on of the naturally gifted, but the encouragement, development and picking up of those who fall occasionally.

Picked correctly, hurdles identify a lack of ability or development in a core skill that is an absolute pre-requisite for further achievement. Picked poorly, it encourages misdirected effort, rote learning or eye-rolling by students as they undertake compulsory make-work.

I spend a lot to time trying to frame what is happening in the course so that my students can keep an eye on their own progress. A lot of what affects a student is nothing to do with academic ability and everything to do with their youth, their problems, their lives and their hang-ups. If I can provide some framing that tells them what is important and when it is important for it to be important, then I hope to provide a set of guides against which students can assess their own abilities and prioritise their efforts in order to achieve success.

Students have enough problems these days, with so many of them working or studying part-time or changing degrees or … well… 21st Century, really, without me adding to it by making the course a black box where no feedback or indicators reach them until I stamp a big red F on their paperwork and tell them to come back next year. If they can still afford it.

Once again, XKCD says it all – “Share Your Knowledge With Joy”

Posted: May 11, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: blogging, education, higher education, identity, learning, randall munroe, teaching, teaching approaches, tools, xkcd Leave a commentIn a recent XKCD post, Randall Munroe asks us why we criticise people when they don’t know something, rather than taking it as an opportunity to inform and delight them. After all, what is the actual benefit of belittling someone if they haven’t happened to have been exposed to the same information as you.

Well, that’s an excellent question. And, if you’re an educator, it’s the essential question.

We know that out students come to us without the information that they need. Because of this, they are regularly going to not know things and, sometimes, that’s going to be frustrating, but that’s what we’d expect.

I’ve run across it a few times myself when I’ve been surprised that people haven’t known basic (and to me common) terms in other languages like French or German. Why should they? I was raised in England, intermittently around French speakers, and have been exposed to European languages in one form or another for 40 years. I studied French at school and have German-speaking friends and colleagues, who I’ve visited. When someone doesn’t know what bon mot, or soupçon means, that’s not actually an indicator of anything, except that they don’t know it yet. Ok, hand up in shame, I have, in the past, been obviously surprised when someone didn’t know something but, over the last few years, I’ve worked really hard to curb it and try to be positive and informative, rather than being a schmuck.

After all, when I was a wine making student, a Microbiology PhD student sneered at me, quite effectively, because I didn’t know how to prepare a certain type of sample. The fact that I had never been shown, it hadn’t been a pre-requisite, and that it was actually his job to show me apparently eluded him on the day. Net result? 10 years later I remember being made to feel small but I still don’t remember how to prepare that sample.

I know what it’s like when someone decides to feel superior through exclusivity, rather than get a kick out of sharing the knowledge. Even if it wasn’t my job, even if knowledge sharing wasn’t something I enjoyed, even if it wasn’t the only ethically defensible choice – I should still be doing the right thing because I know what it’s like to be on the other side.

Thanks again, Randall, for a potted summary, in fun cartoon form, to remind us what it means to not be a schmuck.

Deadlines and Decisions – an Introduction to Time Banking

Posted: May 9, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, higher education, learning, measurement, perry, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, time banking, time management, tools 3 CommentsI’m working on a new project, as part of my educational research, to change the way that students think about deadlines and time estimation. The concept’s called Time Banking and it’s pretty simple. Some schools already give students some ‘slack time’, free extension time that the students manage to allow them to manage their own deadlines. Stanford offers 2 days up front so, at any time in the course, you can claim some extra time and give yourself an extension.

The idea behind Time Banking is that you get extra hours if you hand up your work (to a certain standard) early. These hours can be used later as free extensions for assignment, up to some maximum number of days. This makes deadlines flexible and personalised per student.

Now I know that some of you already have your “Time is Money, Jones!” hats on and may even be waggling a finger. Here’s a picture of what that looks like, if you’re not a-waggling.

“Deadlines are fixed for a reason!”

“We use deadlines to teach professional conduct!”

“This is going to make marking impossible.”

“That’s not the right way to tie a bow tie!”

“It’s the end of civilisation as we know it!” (Sorry, that’s a little hyperbolic)

Of course, some deadlines are fixed. However, looking back over my own activities during the past quarter, I have far more negotiable and mutable deadlines than I do fixed ones. Knowing how to assess my own use of time in the face of a combination of fixed and mutable deadlines is a skill that I refine every year.

If I had up late, telling me to hand up on time or start earlier doesn’t really involve me in the process that’s required: making a decision as to how I’m going to manage all of my commitments over time, rather than panicking when I run into a deadline.

I can’t help thinking that forcing students to treat every assignment deadline as fixed, whether it needs to be or not, doesn’t deal with the student in the way that we try to in every other sphere. It makes them depend upon the deadline from an authority, rather than forcing them to look at their assignment work across a whole semester and plan inside that larger context. How can we produce students who are able to work at the multiplicity or commitment level, sorry, Perry again, if we force them to be authority-dependent dualists in their time management?

Now, before you think I’ve gone mad, there are some guidelines for all of this, as well as the requirement to have a good basis in evidence.

- We must be addressing an existing behavioural problem. (More on this later.)

- Some deadlines are immutable. This includes weekly dependencies, assignments where the solutions are revealed post submission, and ‘end of semester’ close-off dates.

- The assessment of ‘early and satisfactory’ must be low effort for the teacher. We don’t want to encourage handing up empty assignments a week ahead. We want to encourage meeting a certain standard, preferably automatically assessed, to bring student activity forward.

- We have limits on the amount you can bank or spend, to keep assessment of the submitted materials inside the realm of possibility and, again, to reduce unnecessary load on the staff,

- We don’t tolerate bad behaviour. Cheating or system fiddling immediately removes the system from the scheme.

- We provide up-front hours to give all students a base line of extension.

- We integrate this with our existing ‘system problem’ and ‘medical/compassionate problem’ extension systems.

Now, if students don’t have a problem, there’s nothing to fix. If our existing fixed deadline system encouraged students to start their work at the right time and finish in a timely fashion, then by final year, we wouldn’t need anything like this. However, my data from our web submission system clearly indicates the existence of ‘persistently’ late students and, in fact, rather than getting better, we actually start to see some students getting later in second, third and honours years. So, while this isn’t concrete, we’re not seeing the “Nope, no problem here” behaviour that we’d like. So that’s point 1 dealt with – it looks like we have a problem.

Most of the points are technical issues or components of an economic model, but 6 and 7 address a more important issue: equity. Right now, if your on-line submission systems crash the day before the assignment is due, what happens? Everyone who handed in their work has done the right thing but, because you have to grant a one day extension, they actually prioritised their work too early. Not a huge deal in many ways, because students who get their work in early probably march to a different drum anyway, but it makes a mockery of the whole fixed deadline thing. Either the deadline is fixed or it isn’t – by allowing extension on a broad scale for any reason, you’re admitting that your deadline was arbitrary.

We’re trying to make them think harder than that.

How about, instead, you hand out 24 hours of time in the bank. Now the students who handed up early have 24 hours to spend later on and the students who didn’t get it in before the crash have a fair chance to get their work in on time. Student gets sick, your medical extensions are now just managed as time in the bank, reflecting the fact that knock on effects can be far greater than just getting an extension for a single assignment.

But we don’t go crazy. My current thoughts are that we’d limit the students to only starting to count early about 2 days before the assignment is due, and allow a maximum of 3 days extension (greater for medical or compassionate). This keeps it in our marking boundary and also, assuming that you’ve placed your assignments in the context of the appropriate knowledge delivery, keeps the assignments roughly in the same location as the work – not doing the assignment at the beginning of the term and then forgetting the knowledge.

So, cards on the table, I’m writing a paper on this, identifying exactly what I need to look at in order to demonstrate if this is a problem, the literature that supports my approach, the objections to it and the obstacles. I also have to spec the technical system that would support it and , yes, identify the range of assignments for which it would work. It won’t work for everything/everyone or every course. But I suspect it might work very well for some areas.

Could we allow team banking? Course banking? Social sharing? Community involvement (donation to charity for so many hours in the bank at the end of the course)? What could we do by involving students in the elastic management of their own time?

There’s a lot more but I’d love to hear some thoughts on it. I look forward to the discussion!

Spot the Computer Science Student and Win!

Posted: May 8, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, computer science, computer science student, education, higher education, learning, measurement, resources, stereotype, student, teaching approaches 1 CommentCS Students get a pretty bad rap on that whole “stereotype” thing. Given that I’m an evidence-based researcher, let’s do some tests to find out if we can, in fact, spot the CS student. Here’s a quick game for you. Hidden in this image are 3 Computer Science students.

Which ones are they? (You can click on the image to enlarge it.)

I’ll make it easy for you to reference them – we’ll number the rows from the top (A) to the bottom (H) and the images from left to right as 1 to … well, whatever, because the rows aren’t the same length. So the picture with the cactus is A2, ok? Got it? Go!

Who did you pick? Got the details? Now scroll down.

Of course, if you know me at all, you probably know the answer to this already.

They’re ALL Computer Science students – well, they’re found in an image search for “I am a Computer Science student” and, while this is not guaranteed, it means that most of these students are in CS. Now, knowing that, go back and look at the ones you thought were music majors, physicists, business students, economics people. Yes, one or two of them probably look more likely than most but – wait for it – they don’t all look the same. Yeah, you know that, and I know that, but we just have to keep plugging away to make sure that everyone ELSE gets that. Heck, the pictures above are showing less pairs of glasses per person than you would expect from the average and there’s not even one light sabre! WON’T SOMEONE THINK OF THE STEREOTYPES???

This is only page 2 of the Image Search and I picked it because I liked the idea of some inanimate objects being labelled as CS students as well. Oh, that’s right, I said that you’d win something. You know never to trust me with statements unless I’m explicit in my use of terminology now. Sounds like a win to me!

(Of course, the guy with red hair is giving the strong impression that he now knows that you were looking at him on the Internet. I don’t know if you wanted that but that’s just how it is.)

Heroes

Posted: May 7, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, alan turing, Arland D Williams, Arland Williams, bruno schulz, education, heroes, higher education, inspiring students, learning, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches, turing, work/life balance 1 CommentI know that I learn best when I’m inspired and engaged, so I regularly look for things around me that I can bring into the classroom that go beyond “program this” or “design that”. Our students are surrounded by the real world and, unfortunately, it’s easy to understand why they might be influenced by things that are less than inspirational. I don’t want to be negative, but there are so many examples of bad behaviour on the national and international stage that, sometimes, you really wonder why you bother.

So, today, I’m going to talk about four people. Regrettably, three of them some of you won’t be able to talk about because of personal convictions, political considerations or the ages of your class, but I hope that most of you will either have learned something new or remembered something important by the time I’m finished. Are these people actually heroes, given the title of my post? Well, one is a professional inspiration to me, one is an artistic inspiration to me (and reminder of the importance of what I’m doing), one is generally inspiring in the area of democracy and dedication, and the other… well, the other, I can barely look at his picture without wondering if I could ever approach the level of selflessness and heroism that he demonstrated. But I’ll talk about him last.

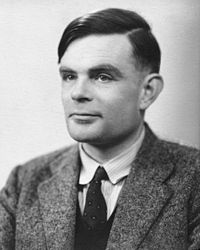

This is Alan Turing, the most likely candidate for the term “Father of Computer Science”. Witty, well-educated, highly intelligent and thoughtful, he was leader in cryptanalysis at Bletchley Park, providing statistical and mathematical genius to breaking codes including the design of the bombe, the machine that attacked Enigma. Importantly, for me as a Computer Scientist, he developed Turing Machines, effectively providing the foundations of studies in the theory of computation. He provided the first detailed design of a computer that used a stored program, very different from the electrical calculators of the day. He defined some of the key terms that we still use in Artificial Intelligence. (There’s so much more but it wouldn’t mean much to you outside the discipline, but he’s well worth looking up.)

Of course, some of you can’t mention Turing to your students, because he was a known homosexual, with a conviction for gross indecency in 1952 after admitting to a consensual homosexual relationship. He had a choice between imprisonment or chemical castration (he chose the latter) and his security clearance was revoked and he was barred from continuing with his security work. He was found dead in 1954, having (most likely) committed suicide.

There is no doubt that the field I am in is the better (or even exists) for Turing having lived and worked in this field. We are poorer for his early loss and, personally, I’m ashamed that persecution based on his sexual orientation may have led to the premature self-administered death of a genius.

Meet Bruno Schulz, author, artist and critic. Schulz wrote some incredible works, contributed murals and was, despite his somewhat hermitic nature, an influential contributor to the arts. Schulz was born and lived, for most of his life, in Drohobych, Galicia. His contributions, although limited by his early death, include the highly influential works “Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass” and “The Street of Crocodiles”. In 1938, he was awarded the Polish Academy’s Golden Laurel award for his works and translations.

I am currently writing a series of stories that were inspired, in part, by the “Sanatorium” with its dreamlike qualities, stories interweaving with unreliable narration and innate and unexpected metamorphoses. Schulz is a fascinating counterpoint to Borges for me, woven with the immersion in Jewish culture I would expect from Singer, but with a different tone that comes from through, even in the English translations I have to read.

We have no more works from Schulz, not even the fragments of the book he was working on at the time of his death “The Messiah”. Why was Schulz killed? After the German invasion of the Soviet Union in the Second World War, Drohobych was occupied and, for a time, Schulz (who was Jewish) was protected by a Gestapo officer who admired his artistic work. Unfortunately, another Gestapo officer, a rival of the first, decided to kill this “personal Jew” and shot Schulz on the way home. You will excuse me for being confusing by referring to neither officer by name.

This person you may have heard of. Fang Lizhi died very recently, a Chinese Astrophysicist who lived in exile for over 22 years, after a life spent trying to pursue science despite being politically persona non grata and, for many years, not being able to publish under his own name. He survived hard labour during his re-education by the worker class during the cultural revolution but continued to fight against what he saw as severe obstacles to the pursuit of his scientific aims, including proscriptive ideological opposition to some of the key ideas required to be a successful astrophysicist or cosmologist.

In 1989, he was highly instrumental in the movement that occupied Tiananmen Square, despite not being directly involved in the protest and, once those protests had been dealt with, he decided that, with his wife, his safety was no longer ensured and he sought refuge at the US Embassy. He remained in the embassy for over a year, while diplomatic negotiations continued. Eventually he was allowed to leave and had an international career in his discipline, as well as speaking regularly on human rights and social responsibility. Of all the people on this list, Professor Fang died of old age, at 76, having managed to escape from the situation in which he found himself.

We talk a lot about academic freedom, or the entitlement to academic freedom, but we often forget that there is a harsh and heavy price imposed for it, depending upon the laws and the governments in which we find ourselves. That is a hard and heavy lesson.

Some of you will not be able to talk about Alan Turing, because he was gay. Some of you may have difficulty discussing Bruno Schulz, because of the involvement of Nazis or because he was a Jew. Some of you have may have stopped reading the moment you saw the picture of Fang Lizhi, because you didn’t want to get into trouble. Please keep reading.

So let me give you the story of the first man on this page. Let me tell you about a man who was a bank investigator. Recently divorced, with a youngest child of 17. I want to tell you about him because his story is the simplest and the most complex. He has no giant academic backstory, no grand contribution to literature, no oppression to fight. He just choose to be good.

In 1982, Arland D. Williams, Jr, was a passenger on board a plane from Washington DC to Florida, Air Florida Flight 90, that took off in freezing weather, iced up, failed to gain altitude and slammed into the 14th Street Bridge across the Potomac. The crash killed four motorists and the plane slid forward, down into the Potomac, with the tail breaking off as it did so. There were 79 people on board. Only 6 made it up and onto the tail, which was still floating.

When the rescue helicopter got there, they started recovering people from the tail section, dropping rescue ropes. Williams caught the rescue ropes multiple times and, instead of using them for himself, he handed them to the other passengers.

Life vests were dropped. Rescue balls. He handed them on.

The helicopter, overloaded and struggling with the conditions, got every other survivor back to shore, sometimes having to pick up the weak survivors multiple times. But Williams made sure that everyone else got helped before he did.

Sadly, tragically, by the time the helicopter came back for him, the tail section had shifted and sank, taking him with it. As it happened, Williams had made so little fuss about himself during his actions that his identity had to be determined after the fact.

It would be easy, and cynical, to describe human beings in terms of animals, given some of the awful things we do. Taking away a man’s livelihood (maybe even killing him) because of who he’s in love with? Killing someone because you have an argument with someone else? Persecuting someone for trying to pursue science or democracy?

Yet their stories survive, and we learn. Slowly, sometimes, but we learn.

It would be easy to assume that everyone, when desperate enough, would scrabble like rats to survive. (Except, of course, that not even rats do that. We just tell ourselves they do because we can’t sometimes recognise that this is just a paltry excuse for human evil.)

Here is your counter example – Arland Williams. Here is your existential proof that revokes the “WE ARE ALL LIKE THIS” Myth. There are so many more. Go back to the top of the page and look at that ordinary, middle-aged man. Look at someone who looked down at the freezing water around him and decided to do something great, something amazing, something heroic.

100 Killer Words (Pleas Reed Allowed)

Posted: May 6, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, blogging, education, higher education, identity, ivory tower, killer words, learning, lighthouse, reflection, teaching Leave a commentWriting over 100,000 words in a year has an impact on a lot of things. It affects the way that you think about whatever it is that you’re writing on. It affects the way that you manage your time, because you have to put aside 30-60 minutes a day. It affects the way that you think about your contact with the world because, when you have a daily deadline, you have to find something interesting every single day.

I have always read a lot. I read quickly and I enjoy it a great deal. But, until recently, apart from technical writing, my reading wasn’t important enough to keep track of. I surfed some pages over there? Oh, that’s nice. But now? Now, if I read something and there’s a germ of an idea, I have to keep track of it because I will need that to put together a post, most often late at night or on weekends. My gadgets and browsers are full of half-ideas, links, open pages, sketches. It changes you, writing and thinking this much in such a short time.

Let me, briefly, tell you how I’ve changed this year. I don’t know what to call this year because it’s most certainly not “The Year of Living Dangerously” or “The Year My Voice Broke” and it’s most certainly not “The Year of Living Biblically”. But let’s leave that for the moment. Let me tell you how I’ve changed.

- I have never used my brain so much, for such an extended period. My day is now full of stories and influences, connections and images, thinking, analysing, preparing and presenting. This is changing me as a person – giving me depth, making me more able to discuss issues, drawing out a lot of the frustration and anger I’ve wrestled with for years.

- I now try to construct working solutions from what I have, rather than excise non-working components. If reading and thinking this much about education has taught me anything, it’s that there is no perfect system and there are no perfect people. Saying that your system would work if only people were better is not achieving anything. You have to build with what you’ve got. People are building amazing systems from ordinary people, inspiration and not much else. No matter how you draw up your standards, setting a perfection bar, which is very different from a quality bar, will just lead to failure, frustration and negativity.

- I can see the possibility of improvement. People, governments, companies, systems – they often disappoint me. I have had the luxury of reading across the world and writing a small fraction of it. For every cruel, vicious, and stupid person, there are so many more other people out there. I have long wondered whether our world will outlast me by much. Am I sure that it will? No. Am I more optimistic that it will? Yes.

But it’s not all beer and skittles. I also work far too much. Along the way, my workaholism has been severely re-engaged. I worked a full (long) week last week and yet, here I am, 5 hours work on Saturday and somewhere along the lines of 8-10 hours on Sunday. That’s not a good change and I have to work out how I can keep all the positive aspects – because the positives are magnificent – without getting drawn down into the maelstrom.

I would like to describe this year as “The Year of Living” because, in many ways, I’ve never felt so alive, so aware, so informed and so capable of changing things in a constructive way. But, until I nail the overwork thing, it doesn’t get that title.

For now, because I’ve written 100,000 words or, 100 kiloWords, I’m going to call it “The Year of Killer Words” and hope that, homophones aside, that there’s some truth to that – that some of my words have brought light into the shadows and killed some monsters. Rather idealistically, that’s how I think of the job that we do – we bring light into dark places. Yes, a University can look like an ivory tower sometimes, and sometimes it is, but lighthouses look much the same – it’s the intention and the function that makes one an elitist nightmare and gives the other its worth and nobility.

That image, up the top? That’s what I think we’re doing when we do it right.