(Reasonable) Argument, Evidence and (Good) Journalism: Is “Crimson” the Colour of Their Faces?

Posted: September 5, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, education, ethics, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking 2 CommentsI ran across a story on the Harvard Crimson about a surprisingly high level of suspected plagiarism in a course, Government 1310. The story opens up simply enough in the realms of fact, where the professor suspected plagiarism behaviour in 10-20 take home exams, which was against published guidelines, and has now expanded to roughly 125 suspicious final exams. There was a brief discussion of the assessment of the course and the steps taken so far by the faculty.

Then, the article takes a weird turn. Suddenly, we have a student account, an anonymous student who doesn’t wish their name to be associated with the plagiarism, who “suspected that Government 1310 was the course in question”. Hello? Why is this… ahhh. Here’s some more:

Though she said she followed the exam instructions and is not being investigated by the Ad Board, she said she thought the exam format lent itself to improper academic conduct.

“I can understand why it would be very easy to collaborate,” said the student

Oh. Collaborate. Interesting. Next we get the Q Guide rating for the course and this course gets 2.54/5 versus the apparent average of 3.91. Then we get some reviews from the Q Guide that “spoke critically of the course’s organisation and the difficulty of the exam questions”.

Spotting a pattern yet?

Another student said that he/she had joined a group of 15 other students just before the submission date and that they had been up all night trying to understand one of the questions (worth 20%).

I submitted this to my students to read and then asked them how they felt about it. Understandably, by the end of the reading, while my students were still thinking about plagiarism, they were thinking that there may have been some… justification. Then we started pulling the article apart.

When we start to look at the article, it becomes apparent that the facts presented all have a rather definite theme – namely that if cheating has occurred, that it has a justification because of the terrible way the course was taught (low Q Guide rating! 16 students confused!)

Now, I can not see the Q Guide data, because when I go to the page I get this information (and I need a Harvard login to go further):

Q Guide

The Q Guide was an annually published guide that reported the results of each year’s course evaluations. Formerly called the CUE Guide, it was renamed the Q Guide in 2007 because the evaluations now include the GSAS and are no longer run solely by the Committee on Undergraduate Education (CUE). In 2009, in place of The Q Guide, Harvard College integrated Q data with the online course selection tool (at my.harvard.edu), providing a simple and easy way to access and compare course evaluation data while planning your course schedule.

So if the article, regarding an exam run in 2012, is referring to the Q Guide for Gov 1310, then it’s one of two things: using an old name for new data (admittedly, fairly likely) or referring to old data. The question does arise, however, whether the Q Guide rating refers to this offering or a previous offering. I can’t tell you which it is because I don’t know. It’s not publicly available and the article doesn’t tell me. (Although you’ll note that the Q Guide text refers to this year‘s evaluations. There’s a part of me that strongly suspects that this is historical data but, of course, I’m speculating.)

However, the most insidious aspect is the presentation of 16 students who are confused about content in a way that overstates their significance. It’s a blatant example of emotive manipulation and encourages the reader to make a false generalisation. There were 279 students enrolled in Gov 1310. 16 is 5.7%. Would I be surprised in somewhere around 5% of my students weren’t capable of understanding all of the questions or thought that some material wasn’t in the course?

No, of course not. That’s roughly the percentage of my students who sometimes don’t know which Dr Falkner is teaching their class. (Hint: one is male and one is female. Noticeably so in both cases.)

I presented this to my Grand Challenge students as part of our studies of philosophical and logical fallacies, discussing how arguments are made to mislead and misdirect. The terrible shame is that, with a detected rate of plagiarism that is this high, I would usually have a very detailed look at the learning and teaching strategies employed (how often are exams being rewritten, how is information being presented, how is teaching being carried out) because this is an amazingly high level of suspected plagiarism.

Despite the misleading journalism presented in the Crimson, the course and its teachers may have to shoulder some responsibility here. As always, just because someone’s argument is badly made, doesn’t mean that it is actually wrong. It’s just disappointing that such a cheap and emotive argument was raised in a way that further fogs an important issue.

As I said to my students today, one of the most interesting way to try to understand a biassed or miscast argument is to understand who the bias favours – cui bono? (To whom the benefit? I am somewhat terrified, on looking for images for this phrase, that it has been highjacked by extremists and conspiracy theorists. It’s a shame because it’s historically beautiful.)

So why would the Crimson run this? It’s pretty manipulative so, unless this is just bad journalism, cui bono?

Having looked up how disciplinary boards are constituted at Harvard, I found a reference that there are three appointed faculty members and:

There are three students appointed to the board as full voting members. Two of these will be assigned to specific cases on a case-by-case basis and will not be in the same division as the student facing disciplinary action.

In this case, the Crimson’s story suddenly looks a lot… darker. If, by publishing this article, they reach the right students and convince them the action of the suspected plagiarists may have been overly influenced by academics who are not performing their duties – then we risk suddenly having a deadlocked board and a deleterious effect on what should have been an untainted process.

The Crimson has further distinguished itself with a follow-up article regarding the uncertainty students are feeling because of the process.

“It’s unfair to leave that uncertainty, given that we’re starting lives,” said the alumnus, who was granted anonymity by The Crimson because he said he feared repercussions from Harvard for discussing the case.

Oh, Harvard, you giant monster, unfairly delaying your decision on a plagiarism case because the lecturers were so very, very bad that students had to cheat. And, what’s worse, you are so evil that students are scared of you – they “fear the repercussions”!

Thank you, Crimson, for providing so much rich fodder for my discussion on how the words “logical argument”, “evidence” and “good journalism” can be so hard to fit into the same sentence.

Let’s Transform Education! (MOOC Hijinks Hilarity! Jinkies!)

Posted: September 1, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, design, education, educational problem, ethics, grand challenge, higher education, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design, work/life balance, workload 4 CommentsI had one of those discussions yesterday that every one in Higher Education educational research comes to dread: a discussion with someone who basically doesn’t believe the educational research and, within varying degrees of politeness, comes close to ignoring or denigrating everything that you’re trying to do. Yesterday’s high point was the use of the term “Mr Chips” to describe the (from the speaker’s perspective) incredibly low possibility of actually widening our entrance criteria and turning out “quality” graduates – his point was that more students would automatically mean much larger (70%) failure rates. My counter (and original point) is that since there is such a low correlation between school marks and University GPA (roughly 40-45% and it’s very noisy) that successful learning and teaching strategies could deal with an influx of supposedly ‘lower quality’ students, because the quality metric that we’re using (terminal high school grade or equivalent) is not a reliable indicator of performance. My fundamental belief is that good education is transformative. We start with the students that schools give us but good, well-constructed, education can, in the vast majority of cases, successfully educate students and transform them into functioning, self-regulating graduates. We have, as a community, carried out a lot of research that says that this works, provided that we are happy to accept that we (academics) are not by any stretch of the imagination the target demographic or majority experience in our classes, and that, please, let’s look at new teaching methods and approaches that actually work in developing the knowledge and characteristics that we’re after.

The “Mr Chips” thing is a reference to a rather sentimental account of the transformative influence of a school master, the eponymous Chips, and, by inference, using it in a discussion of the transformative power of education does cast the perception of my comments on equality of access, linked with educational design and learning systems as transformative technologies, as being seen as both naïve and (in a more personal reading) makes me uncomfortably aware that some people might think I’m talking about myself as being the key catalyst of some sort. One of the nice things about being an academic is that you can have a discussion like this and not actually come to blows over it – we think and argue for a living, after all. But I find this dismissive and rude. If we’re not trying to educate people and transform them, then what the hell are we doing? Advocating inclusion and transformation shouldn’t be seen as grandstanding – it should be seen as our job. I don’t want to be the keystone, I want systems that work and survive individuals, but that individuals can work within to improve and develop – we know this is possible and it’s happening in a lot of places. There are, however, pockets of resistance: people who are using the same old approaches out of laziness, ignorance and a refusal to update for what appear to be philosophical reasons but have no evidence to support them.

Frankly, I’m getting a little irritated by people doubting the value of the volumes of educational research. If I was dealing with people who’d read the papers, I’d be happier, but I’m often dealing with people who won’t read the papers because they just don’t believe that there’s a need to change or they refuse to accept what is in there because of a perceived difficulty in making it work. (A colleague demanded a copy of one of our papers showing the impact of our new approaches on retention – I haven’t heard from him since he got it. This probably means that he’s chosen to ignore it and is going to pretend that he never asked.) Over coffee this morning, musing on this, it occurred to me that at the same time that we’re not getting the greatest amount of respect and love in the educational research community, we’re also worried about the trend towards MOOCs. Many of our concerns about MOOCs are founded in the lack of evidence that they are educationally effective. And I saw a confluence.

All of the educational researchers who are not able to sway people inside their institutions – let’s just ignore them and surge into the MOOCs. We can still teach inside our own places, of course, and since MOOCs are free there’s no commercial conflict – but let’s take all of the research and practice and build a brave new world out in MOOC space that is the best of what we know. We can even choose to connect our in-house teaching into that system if we want. (Yes, we still have the face-to-face issue for those without a bricks-and-mortar campus, but how far could we go to make things better in terms of what MOOCs can offer?) We’re transformers, builders and creators. What could we do with the infinite canvas of the Internet and a lot of very clever people, working with a lot of very other clever people who are also driven and entrepreneurial?

The MOOC community will probably have a lot to say about this, which is why we shouldn’t see this as a hijack or a take-over, and I think it’s helpful to think of this very much as a confluence – a flowing together. I am, not for a second, saying that this will legitimise MOOCs, because this implies that they are illegitimate, but rather than keep fighting battles with colleagues and systems that can defeat 40 years of knowledge by saying “Well, I don’t think so”, let’s work with people who have already shown that they are looking to the future. Perhaps, combining people who are building giant engines of change with the people who are being frustrated in trying to bring about change might make something magical happen? I know that this is already happening in some places – but what if it was an international movement across the whole sector?

Jinkies! (Sorry, the title ran to this and I get to use a picture of a t-shirt with Velma on it!)

The purpose of this is manifold:

- We get to build the systems that we want to, to deliver education to students in the best ways we know.

- We (potentially) help to improve MOOCs by providing strong theory to construct evidence gathering mechanisms that allow us to really get inside what MOOCs are doing.

- More students get educated. (Ok, maybe not in our host institutions, but what is our actual goal anyway?)

- We form a strong international community of educational researchers with common outputs and sharing that isn’t necessarily owned by one company (sorry, iTunesU).

- If we get it right, students vote with their feet and employers vote with their wallets. We make educational research important and impossible to ignore through visible success.

Now this is, of course, a pipe dream in many ways. Who will pay for it? How long will it take before even not-for-pay outside education becomes barred under new terms and conditions? Who will pay my mortgage if I get fired because I’m working on a deliberately external set of courses for students who are not paying to come to my institution?

But, the most important thing, for me, is that we should continue what has been proposed and work more and more closely with the MOOC community to develop exemplars of good practice that have strong, evidence-based outcomes that become impossible to ignore. Much as students use temporal discounting to procrastinate about their work, administrators tend to use a more traditional financial discounting when it comes to what they consider important. If it takes 12 papers and two years of study to justify spending $5,000 on a new tool or time spent on learning design – forget about it. If, however, MOOCs show strong evidence of improving student retention (*BING*), student attraction (*BING*), student engagement (*BING*) and employability – well, BINGO. People will pay money for that.

I’ve spoken before about how successful I had to be before I was tolerated in my pursuit of educational research and, while I don’t normally talk about it in detail because it smacks of hubris and I sincerely believe that I am not a role model of any kind, I hope that you will excuse me so that I can explain why I think it’s crazy as to how successful I had to be in order to become tolerated – and not yet really believed. To summarise, I’m in three research groups, I’ve brought in (as part of a group and individually) somewhere in the order of $0.5M in one non-ed research area, I’ve brought in something like $30-50K in educational research money, I’ve published two A journals (one CS research, one CS ed), two A conferences (both ed) and one B conference (ed/CS) and I have a faculty level position as an Associate Dean and I have a national learning and teaching presence. All of the things on that line – that’s 2012. 2011 wasn’t quite as successful but it wasn’t bad by any stretch of the imagination. I think that’s an unreasonably high bar to pass in order to be allowed the luxury of asking questions about what it is that we’re doing with learning and teaching. But if I can leverage that to work with other colleagues who can then refer to what we’ve done in a way that makes administrators and managers accept the real value of an educational revolution – then my effort is shared over many more people and it suddenly looks like a much better investment of my time.

This is more musing that mission, I’m afraid, and I realise that any amount of this could be shot down but I look forward to some discussion!

Six Heads Are Better Than One

Posted: August 30, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: design, education, educational problem, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentWe had the final project one group feedback session today for the Grand Challenges course. Lots of very impressive posters, as I would have expected with all the work we’ve done on them, but the best outcome was the quality and quantity of useful feedback from the group. There were a number of useful suggestions that identified key improvements to each of the posters.

The framing was important: look at the poster, then discuss how we could improve the presentation, or the underlying analysis. We went through the group in a variety of sequences to get the feedback, so that the last word generally belonged to a different person each time, as did the first. My voice was heard a fair bit, no surprise, but some of the best solutions came from the students, without question.

One of the grand challenges is the formation of a community that can solve the problems and the importance of inter-disciplinary cooperation. By providing an atmosphere where everyone’s voice can be heard, and having the rare opportunity to be able to run a course like this, I’ve been able to demonstrate exactly why this is so important.

Put simply, by yourself you make think of some amazing things, but a group view, with appropriate preparation and framing, will give you the extra things that you didn’t think of – the things that other people will see and, down the track, you might even kick yourself because you didn’t see it.

I don’t want to single out any of the students, because they’re all doing great things, but this is one that’s the closest to completion at the moment. There’s work to do, because the group suggestions put some really good ideas on the table, but the big advantage is that the producer (Heya, M!) was open to suggestions from his peer group and, of course, contributed as much to his peers – including offering to help people develop their expertise in the D3/JavaScript programming combination he used to make this.

250 Internet Maps, a lot of work by a PhD student, a postdoc, several lecturers and a rather busy Grand Challenges student: one picture of the awe-inspiring randomness that is the Internet.

I’m very happy with the progress that these students are made in terms of their knowledge development but also in terms of their overall demonstration of the importance of collaboration and cooperation. We still have a way to go, including some of the most difficult reports and projects, and the first really big marking stage is possibly going to introduce some strain – but I’m optimistic that things will keep going along good lines because I’ve been nothing other than honest about what has to happen, what I’m trying to do and why I believe it’s important.

I think I can sleep well tonight. 🙂

Vale, Neil Armstrong (or, What Happened to my Moon Base?)

Posted: August 27, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, armstrong, blogging, education, educational problem, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, moon, nasa, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, work/life balance Leave a commentNeil Alden Armstrong, the first human to set foot on the Moon, has left us at the age of 82. I don’t remember the moonwalk although, as a baby, I was placed in front of the television to ‘watch’ as, on July 21st, we walked on another world. Growing up, of course, it quickly became apparent that we didn’t go to the Moon anymore, the last walk being when I was 4ish. Apollo 17, the last mission, was in December, 1972, and the planned Apollos (out to 20) were scrubbed. Yes, we got Skylab up into orbit and that was really exciting, as were the docking missions, but it wasn’t THE MOON.

But we were still in space! After all, it was only 8 years later that we all watched as the Space Shuttles started to go into the sky. Well, we were in space. It was obvious that other countries were doing things as well (for those who didn’t grow up with this, it’s fair to say that the USA and USSR didn’t get on for a while so information sharing was limited and often heavily propagandised by both parties) but that glorious shuttle, climbing up into the sky, had taken the baton and we even (finally) managed to get a space station in orbit that was bigger than a breadbox. But, by Moon shot comparisons, it wasn’t quite in the same league.

Now, I’m not for a moment suggesting that space travel has been the best use of our time and money but, goodness, has it been inspirational! We’ve developed some amazing things along the way and we’ve learned a great deal about ourselves – one of which, sadly, is that the future that I am living is not the future that I thought I would inhabit.

Growing up, I made a number of assumptions, based on the talk of the time and the books I read (a lot of which were science fiction) and, looking back on it now, these ideas were very inspirational. Growing up in the England of the early-mid 70s (a cold, lean and unpleasant place) having heroes from space was an important thing for me to have. The messages from the real-life stories of achievement (we went to the Moon! We’re getting rid of smallpox! We’re pushing back disease!) were, and still are, an important part of me. Even where we had dystopia presented to us, it was in order to learn. (The Earth has finite resources, for example, so perhaps we should be living within our means a little better – this is the message of so many works from the mid-late 20th century.)

An Eagle Transporter from the UK television series Space:1999. Note almost complete lack of aerodynamic features, including wing-based control surfaces, because (wait for it) there is no air on the Moon!

But, of course, we have no moon base. We have carried out an incredible and technologically staggering feat to gently drop the new Mars explorer on Mars – but there are no people there. I’m not sure how many times we’ll go back there and my fear is that, within 10 years, we abandon that too. But we aren’t just losing space. A number of our achievements in the face of disease and social equality, for example, are being undermined by deliberate dissemination of disinformation and the shameful exploitation of fear and ignorance.

Sadly, at least some of the people who read this will scoff at the idea that we even went to the Moon. “You rube,” they’re thinking, “Everyone knows it was a giant hoax and cover-up.” The same thing applies to vaccines, where the human failing regarding probability and modelling comes to the fore and the fearful and anecdotal are treasured over the science. Don’t even get me started on the climate change denial movement.

Is this our fault? As scientists did we presume too much in our certainty and, after so many mistakes, have we earned this distrust? Frankly, while scientists have been responsible for some shameful acts of wilful destruction or negligence, I don’t think we deserve to be viewed in such a harsh light. What I believe we’re seeing is the snake oil merchant at its finest – preying on the weak, undermining reality for their own ends, looking into the near term future of the wallet rather than the long term future of us all.

What scares me is that we may be losing our knowledge. That the simplest of ideas in science, that you collect and observe evidence in order to allow you to confirm or contradict your hypotheses, is being overrun by a mad dash towards a certainty based on wilful ignorance where you only see the evidence that agrees with your hypothesis, after the fact, and truth be damned. Should we be spending the money required to go back to the Moon? Perhaps not as it is a lot of money and, goodness knows, we have things to spend it on. But if our reason for not going back to the Moon is that we lack the drive, the imagination, the tenacity or the vision to achieve it – then we are in serious trouble.

People sometimes ask me how many students I need to have in my classroom in order to deliver a lecture. I like to have 80-95%, of course, but my answer is always the same: one. I will not consider it a waste of my time if I spend an hour with a student discussing the ideas and sharing knowledge with them. I want my students to be imaginative, driven, to be able to hang on like a terrier as they search for the truth and to understand that the search for knowledge is important – so I have to try to live that. I have to live it all the time because, all too often, there are too many examples of people ignoring the truth for a comfortable lie, for being famous for being famous, for being famous for being thoughtlessly reactive (shock jock, anyone), for changing their minds for political expediency, for outright lying, and for only valuing quantities and dollars rather than people and knowledge.

What gets me out of bed in the morning is my own set of heroes: my wife, my friends, those in my family who have overcome adversity, the real educators who do their job because they have to and because of their deep and enduring relationship with knowledge, the stars in my firmament. I looked to my own heroes growing up and those heroes wouldn’t have let the world resemble “Silent Running”, “Soylent Green” or “The Omega Man” – they, like me, wanted our children to grow up in a better world. Those films of the 60s and 70s were the product of SF writers looking forward and saying “We don’t want this.” In the absence of vision, in the attack upon science and in the minimisation of majestic and inspirational events, we get ever closer to these stinking, diseased, dying worlds that should only ever exist in our nightmares.

The green in this still from Silent Running is, in theory, almost all of what is left of Earth’s greenery. Not very large, is it?

I grew up thinking that “Silent Running”, a movie where companies ordered the destruction the last of Earth’s biomass because it was too expensive to keep, was hyperbole – at most a cautionary tale. Now, every day, I get out of bed to try and educate a new generation of scientists so that we don’t accidentally or deliberately end up going over exactly that precipice. Thought is the greatest tool that we have and, like any tool, it can work for us and against us. Guiding thought along constructive paths is challenging and it always helps to have a large and visible goal to aim for: navigators need stars or ships get lost.

We need champions. We need champions so large that even our other champions look to them – we need ideas so beautiful and so huge and so captivating that the vast majority of people, when exposed to them, roll up their sleeves and say “I can help.” We need people for your children to aspire to be, because of what they did, not who they are. However, while we have many champions, the giant blazing comets that I had growing up are all dying or dead and it makes me very sad. Yes, there is incredible achievement going on and there are many, many great stories but what does the future look like to someone growing up now?

My future was full of moon bases, flying cars, leisure time, robots, everyone well fed, no war, gender and race equality – what’s our scorecard looking like?

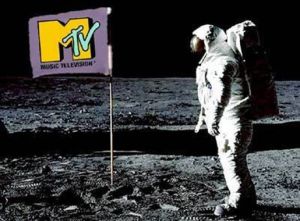

Soon there will be no-one left who walked on the moon. After 2099, there will probably be no-one alive when we did walk on the moon. What happens to the accounts of the Moon then? How long before it becomes a myth? How long before the real footage gets mixed up with Hollywood movies – or the MTV Logo becomes the 22nd century’s view of what happened on the Moon?

Of course, there is no real need to go back to the Moon. There are many other things that we can usefully do with that money and, ethically, we probably should. In terms of inspiration, it’s hard to beat, but that just makes it a challenge to find a problem that is equally big and put it together in a way that we can all see the rightness of it.

If you’ve read this far, thank you, but I have an additional favour to ask of you. This week, if possible, I’d like you to find an extra something, somewhere, that puts an extra champion into your life or into the life of someone else. It doesn’t have to be a person, it just has to be a star to set a course by. Something to look up to in high seas to know why you’re going where you’re going and that the risk is worth it. Have you told one of your living champions how much they mean to you? Have you made the time to share your (I know, precious) time and knowledge with someone else? Can you pin a picture of Hypatia to your pinboard? Rosa Parks? Jon Snow? Curie? Lister? Brunel? da Vinci? The SS Great Britain? Euler? Gauss? Florey? The Wrights? The 1902 Glider or the Wright Flyer 1? Crick/Watson/Franklin (bonus points if you have them in a wrestling ring wearing Luchador masks)? A Crab Canon? Telemann? Steve Kardynal?

“Reserve your right to think, for even to think wrongly is better than not to think at all,” Hypatia of Alexandria.

Have you taken your champion out of your head and told everyone else about them? When we landed on the Moon a vast number of us looked up and, for one moment, we all shared the same vision.

Neil Armstrong lived a good life, one that was useful and surprisingly humble given what he achieved and the position in which he found himself, but he’s gone now and we need more people and inspiration to fill the gap that he left. We need to look up once more.

A Good Friday: Student Brainstorming Didn’t Kill Me!

Posted: August 26, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: community, education, educational problem, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, student perspective, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, workload Leave a commentWe had 19 of last year’s Year 10 Tech School participants back for a brainstorming session yesterday, around the theme “What do you like about ICT/What would you say to other people about ICT.” I started them off with some warm-up exercises, as I only had three hours in total. We started with “One word to describe Tech School 2011”, “two words to describe anything you learnt or used from it”, and “three words to discuss what you think about ICT”. The last one got relaxed quickly as people started to ask whether they could extend it. We split them into tables and groups got pads of post-it notes. Get an idea, write it down, slam it on the table *thump*.

After they had ideas all over the table, I asked them to start assembling them into themes – how would they make sentences or ideas out of this. The most excellent Justine, who did all of the hard work in setting this up (thank you!), had pre-printed some pages of images so the students could cut these out and paste them into places to convey the idea. We had four groups so we ended up with four initial posters.

Floating around, and helping me to facilitate, were Matt and Sami, both from my GC class and they helped to keep the groups moving, talking to students, drawing out questions and also answering the occasional question about the Bachelor of Computer Science (Advanced) and Grand Challenges.

We took a break for two puzzles (Eight Queens and combining the digits from 1 to 9 to equal 100 with simple arithmetic symbols) and then I split the groups up to get them to look at each other’s ideas and maybe get some new ideas to put onto another poster.

Yeah, that didn’t go quite as well. We did get some new ideas but it became obvious that we either needed to have taken a longer break, or we needed some more scaffolding to take the students forward along another path. Backtracking is a skill that takes a while to learn and, even with the graphic designer walking around trying to get some ideas going, we were tapping out a bit by the time that the finish arrived.

However, full marks to the vast majority of the participants who gave me everything that they could think of – with a good spread across schools and regions, as well as a female:male ratio of about 50%, we got a lot of great thoughts that will help us to talk to other students and let them know why they might want to go into ICT… or just come to Uni!

I didn’t let the teachers off the hook either and they gave us lots of great stuff to put into our outreach program. As a hint, I’ve never met yet a teacher at one of these events who said “Oh no, we see enough Uni people and students in the schools”, the message is almost always “Please send more students to talk to our students! Send more info!” The teachers are as, if not more, dedicated to getting students into Uni so that’s a great reminder that we’re all trying to do the same thing.

So, summary time, what worked:

- Putting the students into groups, armed with lots of creative materials, and asking them what they honestly thought. We got some great ideas from that.

- Warming them up and then getting them into story mode with associated pictures. We have four basic poster themes that we can work on.

- Giving everyone a small gift voucher for showing up after the fact, with no judging quality of ideas. That just appeals to my nature – I have no real idea what effect that had but I didn’t have to tell anyone that they were wrong (or less than right) because that wasn’t the aim of today.

- Getting teachers into a space where they could share what they needed from us as well.

What needs review or improvement:

- I need to look at how idea refinement and recombination might work in a tight time frame like this. I think, next time, I’ll get people to decompose the ideas to a mind map hexagon or something like that – maybe even sketch up the message graphically? Still thinking.

- I need more helpers. I had three and I think that a couple more would be good, as close to student age as possible.

- The puzzles in the middle should have naturally led to new group formation.

- Setting it an hour later so that everyone can get there regardless of traffic.

So, thanks again to Justine and Joh for making this work and believing in it enough to give it a try – I believe it really worked and, to be honest, far better than I thought it would but I can see how to improve it. Thanks to Matt and Sami for their help and I really hope that seeing that I actually believe all that stuff I spout in lectures wasn’t too weird!

But. of course, my thanks to the students and teachers who came along and took part in something just because we asked if they’d like to come back. Yeah, I know the motives varied but a lot of great ideas came out and I think it’ll be very helpful for everyone.

Onwards to the posters!

More Thoughts on Partnership: Teacher/Student

Posted: August 23, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, blogging, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, measurement, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, universal principles of design Leave a commentI’ve just received some feedback on an abstract piece that is going into a local educational research conference. I talked about the issues with arbitrary allocation of deadlines outside of the framing of sound educational design and about how it fundamentally undermines any notion of partnership between teacher and student. The responses were very positive although I’m always wary when people staring using phrases like “should generate vigorous debate around expectations of academics” and “It may be controversial, but [probably] in a good way”. What interests me is how I got to the point of presenting something that might be considered heretical – I started by just looking at the data and, as I uncovered unexpected features, I started to ask ‘why’ and that’s how I got here.

When the data doesn’t fit your hypothesis, it’s time to look at your data collection, your analysis, your hypothesis and the body of evidence supporting your hypothesis. Fortunately, Bayes’ Theorem nicely sums it up for us: your belief in your hypothesis after you collect your evidence is proportional to how strongly your hypothesis was originally supported, modified by the chances of seeing what you did given the existing hypothesis. If your data cannot be supported under your hypothesis – something is wrong. We, of course, should never just ignore the evidence as it is in the exploration that we are truly scientists. Similarly, it is in the exploration of our learning and teaching, and thinking about and working on our relationship with our students, that I feel that we are truly teachers.

Once I accepted that I wasn’t in competition with my students and that my role was not to guard the world from them, but to prepare them for the world, my job got easier in many ways and infinitely more enjoyable. However, I am well aware that any decisions I make in terms of changing how I teach, what I teach or why I teach have to be based in sound evidence and not just any warm and fuzzy feelings about partnership. Partnership, of course, implies negotiation from both sides – if I want to turn out students who will be able to work without me, I have to teach them how and when to negotiate. When can we discuss terms and when do we just have to do things?

My concern with the phrase “everything is negotiable” is that it, to me, subsumes the notions that “everything is equivalent” and “every notion is of equal worth”, neither of which I hold to be true from a scientific or educational perspective. I believe that many things that we hold to be non-negotiable, for reasons of convenience, are actually negotiable but it’s an inaccurate slippery slope argument to assume that this means that we must immediately then devolve to an “everything is acceptable” mode.

Once again we return to authenticity. There’s no point in someone saying “we value your feedback” if it never shows up in final documents or isn’t recorded. There’s no point in me talking about partnership if what I mean is that you are a partner to me but I am a boss to you – this asymmetry immediately reveals the lack of depth in my commitment. And, be in no doubt, a partnership is a commitment, whether it’s 1:1 or 1:360. It requires effort, maintenance, mutual respect, understanding and a commitment from both sides. For me, it makes my life easier because my students are less likely to frame me in a way that gets in the way of the teaching process and, more importantly, allows them to believe that their role is not just as passive receivers of what I deign to transmit. This, I hope, will allow them to continue their transition to self-regulation more easily and will make them less dependent on just trying to make me happy – because I want them to focus on their own learning and development, not what pleases me!

One of the best definitions of science for me is that it doesn’t just explain, it predicts. Post-hoc explanation, with no predictive power, has questionable value as there is no requirement for an evidentiary standard or framing ontology to give us logical consistency. Seeing the data that set me on this course made me realise that I could come up with many explanations but I needed a solid framework for the discussion, one that would give me enough to be able to construct the next set of analyses or experiments that would start to give me a ‘why’ and, therefore, a ‘what will happen next’ aspect.

Short and Sweet

Posted: August 21, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, community, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, workload 1 CommentWell, it’s official. I’ve started to compromise my ability to work through insufficient rest. Despite reducing my additional work load, chewing through my backlog is keeping me working far too much and, as you can tell from the number and nature of the typos in these posts, it’s affecting me. I am currently reorganising tasks to see what I can continue to fit in without compromising quality, which means this week a lot of e-mail is being sent to sort out my priorities.

This weekend, I’m sitting down to brainstorm the rest of 2012 and work out what has to happen when – nothing is going to sneak up on me (again) this year.

In very good news, we have 18 students coming back for the pilot activity of “Our students, their words” where we ask students who love ICT an important question – “what do you like and why do you think someone else might like it?” We’re brainstorming with the students for all of Friday morning and passing their thoughts (as research) to a graphic designer to get some posters made. This is stage 1. Stage 2, the national campaign, is also moving – slowly but surely. This is why I really need to rest: I’m getting to the point where it’s important that I am at my best and brightest. Sleeping in and relaxing is probably the best thing I can do for the future of ICT! 🙂

Rather than be a hypocrite, I’m switching to ultra-short posts until I’m rested up enough to work properly again.

See you tomorrow!

Talk to the duck!

Posted: August 17, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, grand challenge, higher education, principles of design, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, time banking, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentI’ve had a funny day. Some confirmed acceptances for journals and an e-mail from a colleague regarding a collaboration that has stalled. When I set out to readjust my schedule to meet a sustainable pattern, I had a careful look at everything I needed to do but I overlooked one important thing: it’s easier to give the illusion of progress than it is to do certain things. For example, I can send you a ‘working on it’ e-mail every week or so and that takes me about a minute. Actually doing something could take 4-8 hours and that’s a very large amount of time!

So, today was a hard lesson because I’ve managed to keep almost all of the balls in the air, juggling furiously, as I trim down my load but this one hurts. Right now, someone probably thinks that I don’t care about their project – which isn’t true but it fell into the tough category of important things that needs a lot of work to get to the next stage. I’ve sent an apologetic and embarrassed e-mail to try and get this going again – with a high prioritisation of the actual work – but it’s probably too late.

The project in question went to a strange place – I was so concerned about letting the colleague down that I froze up every time I tried to do the work. Weird but true and, ultimately, harmful. But, ultimately, I didn’t do what I said I’d do and I’m not happy.

So how can I turn this difficult and unpleasant situation into something that I can learn from? Something that my students can benefit from?

Well, I can remember that my students, even though they come in at the start of the semester, often come in with overheads and burdens. Even if it’s not explicit course load, it’s things like their jobs, their family commitments, their financial burdens and their relationships. Sometimes it’s our fault because we don’t correctly and clearly specify prerequisites, assumed knowledge and other expectations – which imposes a learning burden on the student to go off and develop their own knowledge on their own time.

Whatever it is, this adds a new dimension to any discussion of time management from a student perspective: the clear identification of everything that has to be dealt with as well as their coursework. I’ve often noticed that, when you get students talking about things, that halfway through the conversation it’s quite likely that their eyes will light up as they realise their own problem while explaining things to other people.

There’s a practice in software engineering that is often referred to as “rubber ducking”. You put a rubber duck on a shelf and, when people are stuck on a problem, they go and talk to the duck and explain their problem. It’s amazing how often that this works – but it has to be encouraged and supported to work. There must be no shame in talking to the duck! (Bet you never thought that I’d say that!)

I’m still unhappy about the developments of today but, for the purposes of self-regulation and the development of mature time management, I’ve now identified a new phase of goal setting that makes sense in relation to students. The first step is to work out what you have to do before you do anything else, and this will help you to work out when you need to move your timelines backwards and forwards to accommodate your life.

This may actually be one of the best reasons for trying to manage your time better – because talking about what you have to do before you do any other assignments might just make you realise that you are going to struggle without some serious focus on your time.

Or, of course, it may not. But we can try. We can try with personal discussions, group discussions, collaborative goal setting – students sitting around saying “Oh yeah, I have that problem too! It’s going to take me two weeks to deal with that.” Maybe no-one will say anything.

We can but try! (And, if all else fails, I can give everyone a duck to talk to. 🙂 )

Group feedback, fast feedback, good feedback

Posted: August 16, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, collaboration, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, grand challenge, in the student's head, plagiarism, principles of design, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, vygotsky Leave a commentWe had the “first cut” poster presentation today in my new course. Having had the students present their pitches the previous week, this week was the time to show the first layout – put up your poster and let it speak for itself.

The results were, not all that surprisingly, very, very good. Everyone had something to show, a data story to tell and some images and graphs that told the story. What was most beneficial though was the open feedback environment, where everyone learned something from the comments on their presentation. One of my students, who had barely slept for days and was highly stressed, got some really useful advice that has given him a great way forward – and the ability to go to bed tonight with the knowledge that he has a good path forward for the next two weeks.

Working as a group, we could agree as a group, discuss and disagree, suggest, counter-suggest, develop and enhance. My role in all of this is partially as a ‘semi-expert’ but also as a facilitator. Keep the whole thing moving, keep it to time, make sure that everyone gets a good opportunity to show their work and give and receive feedback.

The students all write down their key feedback, which is scanned as a whole and put on the website so that any good points that went to anyone can now be used by anyone in the group. The feedback is timely, personal and relevant. Everyone feels that these sessions are useful and the work produced reflects the advantages. But everyone talks to everyone else – it’s compulsory. Come to the session, listen and then share your thoughts.

This, of course, reveals one of my key design approaches: collaboration is ok and there is no competitiveness. Read anything about the grand challenges and you keep seeing the word ‘community’ through it. Solid and open communities, where real and effective sharing happens, aren’t formed in highly competitive spaces. Because the students have unique projects, they can share ideas, references and even analysis techniques without plagiarism worries – because they can attribute without the risk of copying. Because there is no curve grading, helping someone else isn’t holding you back.

Because of this, we have already had two informal workshop groups form to address issues of analysis and software, where knowledge passes from person to person. Before today’s first cut presentation, a group was sitting outside, making suggestions and helping each other out – to achieve some excellent first cut results.

Yes, it’s a small group so, being me, now I’m worrying about how I would scale this up, how I would take this out to a large first-year class, how I would get it to a school group. This groups need careful facilitation and the benefit of inter-group communication is derived from everyone in the group having a voice. The number of interactions scale with the square of the group size, so there’s a finite limit to how many people I can have in the group and fit it into a two-hour practical session. If I split a larger class into sub-groups, I lose the advantage of everyone see in everyone else’s work.

But this can be solved, potentially with modern “e-” techniques, or a different approach to preparation, although I can’t quite see it yet. There’s a part of me that thinks “Ask these students how they would approach it”, because they have viewpoints and experience in this which complements mine.

Every week that goes by, I wonder if we will keep improving, and keep rewarding the (to be honest) risk that we’re taking in running a small course like this in leaner times. And, every week, the answer is a resounding “yes”!

Here’s to next week!

Putting it all together – discussing curriculum with students

Posted: August 15, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, collaboration, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, popeye, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, wimpy, workload Leave a commentOne of the nice things about my new grand challenges course is that the lecture slots are a pre-reading based discussion of the grand challenges in my discipline (Computer Science), based on the National Science Foundation’s Taskforce report. Talking through this with students allows us to identify the strengths of the document and, perhaps more interestingly, some of its shortfalls. For example, there is much discussion on inter-disciplinary and international collaboration as being vital, followed by statements along the lines of “We must regain the ascendancy in the discipline that we invented!” because the NSF is, first and foremost, a US-funded organisation. There’s talk about providing the funds for sustainability and then identifying the NSF as the organisation giving the money, and hence calling the shots.

The areas of challenge are clearly laid out, as are the often conflicting issues surrounding the administration of these kinds of initiative. Too often, we see people talking about some amazing international initiative – only to see it fail because nobody wants to go first, or no country/government wants to put money up that other people can draw on until everyone does it at the same time.

In essence, this is a timing and trust problem. If we may quote Wimpy from the Popeye cartoons:

The NSF document lays bare the problem we always have: those who have the hamburgers are happy to talk about sharing the meal but there are bills to be paid. The person who owns the hamburger stand is going to have words with you if you give everything away with nothing to show in return except a promise of payment on Tuesday.

Having covered what the NSF considered important in terms of preparing us for the heavily computerised and computational future, my students finished with a discussion of educational issues and virtual organisations. The educational issues were extremely interesting because, having looked at the NSF Taskforce report, we then looked at the ACM/IEEE 2013 Computer Science Strawman curriculum to see how many areas overlapped with the task force report. Then we looked at the current curriculum of our school, which is undergoing review at the moment but was last updated for the 2008 ACM/IEEE Curriculum.

What was pleasing was, rom the range of students, how many of the areas were being addressed throughout our course and how much overlap there was between the highlighted areas of the NSF Report and the Strawman. However, one of the key issues from the task force report was the notion of greater depth and breadth – an incredible challenge in the time-constrained curriculum implementations of the 21st century. Adding a new Knowledge Area (KA) to the Strawman of ‘Platform Dependant Computing’ reflects the rise of the embedded and mobile device yet, as the Strawman authors immediately admit, we start to make it harder and harder to fit everything into one course. Combine this with the NSF requirement for greater breadth, including scientific and mathematical aspects that have traditionally been outside of Computing, and their parallel requirement for the development of depth… and it’s not easy.

The lecture slot where we discussed this had no specific outcomes associated with it – it was a place to discuss the issues arising but also to explain to the students why their curriculum looks the way that it does. Yes, we’d love to bring in Aspect X but where does it fit? My GC students were looking at the Ethics aspects of the Strawman and wondered if we could fit Ethics into its own 3-unit course. (I suspect that’s at least partially my influence although I certainly didn’t suggest anything along these lines.) “That’s fine,” I said, “But what do we lose?”

In my discussions with these students, they’ve identified one of the core reasons that we changed teaching languages, but I’ve also been able to talk to them about how we think as we construct courses – they’ve also started to see the many drivers that we consider, which I believe helps them in working out how to give feedback that is the most useful form for us to turn their needs and wants into improvements or developments in the course. I don’t expect the students to understand the details and practice of pedagogy but, unless I given them a good framework, it’s going to be hard for them to communicate with me in a way that leads most directly to an improved result for both of us.

I’ve really enjoyed this process of discussion and it’s been highly rewarding, again I hope for both sides of the group, to be able to discuss things without the usual level of reactive and (often) selfish thinking that characterises these exchanges. I hope this means that we’re on the right track for this course and this program.