Gamification: What Happens If All Of The Artefacts Already Exist

Posted: September 4, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, educational problem, feedback, games, higher education, in the student's head, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches, tools Leave a commentI was reading an article today in May/June’s “Information Age”, the magazine of the Australian Computer Society, entitled “Gamification Goes Mainstream”. The article identified the gaming mechanics that could be added to businesses to improve engagement and work quality/productivity by employees. These measures are:

- Points: Users get points for achievements and can spend the points on prizes.

- Levelling: Points get harder to get as the user masters the systems.

- Badges: Badges are awarded and become part of the user’s “trophy page”, accompanying any comments made by the user.

- Leader Boards: Users are ranked by points or achievement.

- Community: Collaborative tools, contests, sharing and forums.

Now, of course, there’s a reason that things exist like in games and that’s because most games are outside of the physical world and, in the absence of the natural laws that normally make things happen and ground us, we rely upon these mechanics to help us to assess our progress through the game and provide us with some reward for our efforts. Now, while I’m a great believer in using whatever is necessary to make work engaging and to make like more enjoyable, I do wonder about the risk of setting up parallel systems that get people to focus on things other than their actual work.

Yes, yes, we all know I have issues with extrinsic motivations but let’s look again at the list of measures above, which would normally be provided in a game to allow us to make sense of the artificial world in which we find ourselves, and think about how they apply already in a workplace.

- Points that can be used to purchase things: I think that we call this money. If I provide a points system for buying company things then I’ve created a second economy that is not actually money.

- Levelling: Oh, wait, now it’s hard to spend the special points that I’ve been given so I’ve not only created a second economy, I’ve started down the road towards hyperinflation by devaluing the currency. (Ok, so the promotional system works here in my industry like that – our ranks are our levels, which isn’t that uncommon.)

- Badges: Plaques for special achievement, awards, post-nominal letters, Fellowships – anything that goes on the business card is effectively a badge.

- Leader Boards: Ok, this is something that we don’t often see in the professional world but, let’s face it, if you’re not on top then you’re not the best. Is that actually motivational or soul-destroying? Of course, if we don’t have it yet, then you do have to wonder why, given every other management trend seems to get a workout occasionally. I should note that I have seen leader boards at my workplace which have been ‘anonymised’ but given that I can see myself I can see where I sit – now not only do I know if am not top, I don’t know who to ask about how to get better, which has been touted as one of the reasons to identify the stars in the first place.

- Community: We do have collaborative tools but they are focussed on helping us achieve our jobs, not on achieving orthogonal goals associated with a gaming system. We also have comment forums, discussion mechanisms such as mailing lists and the like. Contests? No. We don’t have contests. Do we? Oh wait, national competitive grant schemes, local teaching schemes, competitive bidding for opportunities.

Now if people aren’t engaging with the tasks that are expected of them (let’s assume reasonably) then, yes, we should find ways to make things more interesting to encourage participation. However, talking about all of the game mechanics above, it’s obviously going to take more thought than just picking a list of things that we are already doing and providing an alternative system that somehow makes everything really interesting again.

I should note that the article does sound a cautionary tone, from one of the participants, who basically says that it’s too soon to see how effective these schemes are and, of course, Kohn is already waggling a finger at setting up a prize/compliance expectation. So perhaps the lesson here is “how can we take what we already have and work out how to make it more interesting” rather than taking the lessons in required constructions of phenomena from a completely artificial environment where we have to define gravity in order to make things fall. Gamification shows promise in certain direction, mainly because there’s a lot of fun implicit in the whole process, but the approaches need to be carefully designed to make sure that we don’t accidentally reinvent the same old wheel.

The Precipice of “Everything’s Late”

Posted: September 3, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, education, feedback, higher education, learning, measurement, research, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking 7 CommentsI spent most of today working on the paper that I alluded to earlier where, after over a year of trying to work on it, I hadn’t made any progress. Having finally managed to dig myself out of the pit I was in, I had the mental and timeline capacity to sit down for the 6 hours it required and go through it all.

In thinking about procrastination, you have to take into account something important: the fact that most of us work in a hyperbolic model where we expend no effort until the deadline is right upon us and then we put everything in, this is temporal discounting. Essentially we place less importance on things in the future than the things that are important to us now. For complex, multi-stage tasks over some time this is an exceedingly bad strategy, especially if we focus on the deadline of delivery, rather than the starting point. If we underestimate the time it requires and we construct our ‘panic now’ strategy based on our proximity to the deadline, then we are at serious risk of missing the starting point because, when it arrives, it just won’t be that important.

Now, let’s increase the difficulty of the whole thing and remember that the more things we have to think about in the present, the greater the risk that we’re going to exceed our capacity for cognitive load and hit the ‘helmet fire’ point – we will be unable to do anything because we’ve run out of the ability to choose what to do effectively. Of course, because we suffer from a hyperbolic discounting problem, we might do things now that are easy to do (because we can see both the beginning and end points inside our window of visibility) and this runs the risk that the things we leave to do later are far more complicated.

This is one of the nastiest implications of poor time management: you might actually not be procrastinating in terms of doing nothing, you might be working constantly but doing the wrong things. Combine this with the pressures of life, the influence of mood and mental state, and we have a pit that can open very wide – and you disappear into it wondering what happened because you thought you were doing so much!

This is a terrible problem for students because, let’s be honest, in your teens there are a lot of important things that are not quite assignments or studying for exams. (Hey, it’s true later too, we just have to pretend to be grownups.) Some of my students are absolutely flat out with activities, a lot of which are actually quite useful, but because they haven’t worked out which ones have to be done now they do the ones that can be done now – the pit opens and looms.

One of the big advantages of reviewing large tasks to break them into components is that you start to see how many ‘time units’ have to be carried out in order to reach your goal. Putting it into any kind of tracking system (even if it’s as simple as an Excel spreadsheet), allows you to see it compared to other things: it reduces the effect of temporal discounting.

When I first put in everything that I had to do as appointments in my calendar, I assumed that I had made a mistake because I had run out of time in the week and was, in some cases, triple booked, even after I spilled over to weekends. This wasn’t a mistake in assembling the calendar, this was an indication that I’d overcommitted and, over the past few months, I’ve been streamlining down so that my worst week still has a few hours free. (Yeah, yeah, not perfect, but there you go.) However, there was this little problem that anything that had been pushed into the late queue got later and later – the whole ‘deal with it soon’ became ‘deal with it now’ or ‘I should have dealt with that by now’.

Like students, my overcommitment wasn’t an obvious “Yes, I want to work too hard” commitment, it snuck in as bits and pieces. A commitment here, a commitment there, a ‘yes’, a ‘sure, I can do that’, and because you sometimes have to make decisions on the fly, you suddenly look around and think “What happened”? The last thing I want to do here is lecture, I want to understand how I can take my experience, learn from it, and pass something useful on. The basic message is that we all work very hard and sometimes don’t make the best decisions. For me, the challenge is now, knowing this, how can I construct something that tries and defeats this self-destructive behaviour in my students?

This week marks the time where I hope to have cleared everything on the ‘now/by now’ queue and finally be ahead. My friends know that I’ve said that a lot this year but it’s hard to read and think in the area of time management without learning something. (Some people might argue but I don’t write here to tell you that I have everything sorted, I write here to think and hopefully pass something on through the processes I’m going through.)

Warning: Objects in Mirror May Appear Important Because They Appear Closer

Posted: August 31, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, educational problem, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, learning, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, workload 1 CommentI had an interesting meeting with one of my students who has been trying to allocate his time to various commitments, including the project that he’s doing with me. He had been spending most of his time on an assignment for another course and, while this assignment was important, I had to carry out one of the principle duties of the supervisor: pointing out the obvious when people have their face pressed too close to the window, staring at the things that are close.

There are three major things a project supervisor does: kick things off and give some ideas, tell the student when they’re not making good progress and help them to get back on track, and stop them before they run off into the distance and get them to write it all down as a thesis of some sort.

So, in our last meeting, I asked the student how much the other assignment was worth.

“About 10%.”

How much is your project work in terms of total courses?

“4 courses worth.”

So the project is 40 times the value of that assignment that has taken up most of your time? What’s that – 4,000%?

…

To his credit, he has been working along and it’s not too late yet, by any stretch of the imagination, but a little perspective is always handy. He has also started to plan his time out better and, most rewardingly, appreciates the perspective. This, to be honest, is the way that I like it: nothing bad has happened, everyone’s learned something. Hooray!

I sometimes wonder if it’s one of the crucial problems that we face as humans. Things that are close look bigger, whether optically because of how eyes work or because of things that are due tomorrow seem to have so much more importance than much, much bigger tasks due in four weeks. Oh, we could start talking about exponential time distributions or similar things but I prefer the comparison with the visual illusion.

Just because it looks close doesn’t mean it’s the biggest thing that you have to worry about.

Marcus Aurelius: Says It All, Really.

Posted: August 28, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: community, education, ethics, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, marcus aurelius, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentI’m reading Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, which I read years ago but had the opportunity to pick up again for $8.33. (Woohoo, cheap Penguins!) The book is full of great thoughts and aphorisms but there are three, from Book 12, that have always appealed to me:

13, How absurd – and a complete stranger to the world – is the man who is surprised at any aspect of his experience in life!

15, The light of a lamp shines on and does not lose its radiance, until it is extinguished. Will then the truth, justice, and self-control which fuel you fail before your own end?

17, If it is not right, don’t do it; if it is not true, don’t say it.

I feel 13 a lot – and it’s rather embarrassing because I am often surprised by the world but I suspect that’s because I’m in my own head a lot. 15 is something I’ve said before, in different ways and never as elegantly, and it’s a great image.

17, however, says it all to me. It’s incredibly, naïvely simple but that is part of its appeal. It is probably one of the greatest maxims for teaching, in terms of commitment, in terms of content and in terms of bravery when faced with the choice of presenting something that you know to be true – and something that you’ve been told to teach.

Marcus Aurelius was an Emperor, philosopher (philosopher king, even, a reputation he gained in his own life time) and the Emperor Hadrian, his sponsor, had a special nickname for him – “Verissimus”, the most true. Herodian wrote: “he gave proof of his learning not by mere words or knowledge of philosophical doctrines but by his blameless character and temperate way of life.”

I spoke earlier this week of champions. It’s nice to read Marcus Aurelius and be reminded of how many amazing thinkers have been contributing to our shared literary legacy over 2000 years.

“If it is not right, don’t do it; if it is not true, don’t say it.”

More Thoughts on Partnership: Teacher/Student

Posted: August 23, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: authenticity, blogging, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, measurement, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, universal principles of design Leave a commentI’ve just received some feedback on an abstract piece that is going into a local educational research conference. I talked about the issues with arbitrary allocation of deadlines outside of the framing of sound educational design and about how it fundamentally undermines any notion of partnership between teacher and student. The responses were very positive although I’m always wary when people staring using phrases like “should generate vigorous debate around expectations of academics” and “It may be controversial, but [probably] in a good way”. What interests me is how I got to the point of presenting something that might be considered heretical – I started by just looking at the data and, as I uncovered unexpected features, I started to ask ‘why’ and that’s how I got here.

When the data doesn’t fit your hypothesis, it’s time to look at your data collection, your analysis, your hypothesis and the body of evidence supporting your hypothesis. Fortunately, Bayes’ Theorem nicely sums it up for us: your belief in your hypothesis after you collect your evidence is proportional to how strongly your hypothesis was originally supported, modified by the chances of seeing what you did given the existing hypothesis. If your data cannot be supported under your hypothesis – something is wrong. We, of course, should never just ignore the evidence as it is in the exploration that we are truly scientists. Similarly, it is in the exploration of our learning and teaching, and thinking about and working on our relationship with our students, that I feel that we are truly teachers.

Once I accepted that I wasn’t in competition with my students and that my role was not to guard the world from them, but to prepare them for the world, my job got easier in many ways and infinitely more enjoyable. However, I am well aware that any decisions I make in terms of changing how I teach, what I teach or why I teach have to be based in sound evidence and not just any warm and fuzzy feelings about partnership. Partnership, of course, implies negotiation from both sides – if I want to turn out students who will be able to work without me, I have to teach them how and when to negotiate. When can we discuss terms and when do we just have to do things?

My concern with the phrase “everything is negotiable” is that it, to me, subsumes the notions that “everything is equivalent” and “every notion is of equal worth”, neither of which I hold to be true from a scientific or educational perspective. I believe that many things that we hold to be non-negotiable, for reasons of convenience, are actually negotiable but it’s an inaccurate slippery slope argument to assume that this means that we must immediately then devolve to an “everything is acceptable” mode.

Once again we return to authenticity. There’s no point in someone saying “we value your feedback” if it never shows up in final documents or isn’t recorded. There’s no point in me talking about partnership if what I mean is that you are a partner to me but I am a boss to you – this asymmetry immediately reveals the lack of depth in my commitment. And, be in no doubt, a partnership is a commitment, whether it’s 1:1 or 1:360. It requires effort, maintenance, mutual respect, understanding and a commitment from both sides. For me, it makes my life easier because my students are less likely to frame me in a way that gets in the way of the teaching process and, more importantly, allows them to believe that their role is not just as passive receivers of what I deign to transmit. This, I hope, will allow them to continue their transition to self-regulation more easily and will make them less dependent on just trying to make me happy – because I want them to focus on their own learning and development, not what pleases me!

One of the best definitions of science for me is that it doesn’t just explain, it predicts. Post-hoc explanation, with no predictive power, has questionable value as there is no requirement for an evidentiary standard or framing ontology to give us logical consistency. Seeing the data that set me on this course made me realise that I could come up with many explanations but I needed a solid framework for the discussion, one that would give me enough to be able to construct the next set of analyses or experiments that would start to give me a ‘why’ and, therefore, a ‘what will happen next’ aspect.

The Road Lines and the Fences

Posted: August 20, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: design, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking 1 CommentTeaching is a highly rewarding activity and there are many highs to be had along the way: the students who ‘get it’, the students that you help back from the edge of failure, the ones who you extend opportunities to who take them, and the (small) group who come back some years later and thank you. They’re all great. One of the best ways to spot those students are at risk or already in trouble is, of course, to put in some structure and assessment to give you reports on when people are having trouble. A good structure will include things like a set of mechanisms that allow the student to determine where they are, and mechanisms that alert you if the student is in terrible trouble. Of course, the first set can also be viewed by you, as you are probably instrumental in the feedback, but we’re not really talking summative and formative, we’re talking guidance and then disaster prevention.

It’s like driving on the roads. They paint lines on the roads that tell you where to go and sometimes you even get the things that go “BARRUMP BARRUMP BARRUMP” which is secret code for “You are driving in a country that drives on the other side from you, back into your lane.” However, these are for the driver to use to determine which position they should hold on the road. In this case, it’s not just a personal guidance, it’s a vital social compact that allows us to drive and not have it look like The Road Warrior.

But the key point for these lines is that they do not actually have any ability to physically restrain your car. Yes, we can observe people swerving over the road, whether police or cameras are viewing, but that little white or yellow line doesn’t do anything except give you a reference point.

When we are serious about the danger, we put up large pieces of steel and concrete – we build fences. The fences stop people from heading over into the precipice, they stop people from crossing into oncoming traffic and they even can deflect noise away from houses to help other people. Again, we have an individual and a social aspect to these barriers but these are no ‘ignore it’ mechanism – this is physics!

The analogy is excellent for the barriers and measures that we can use in teaching. An aware student, one who needs the occasional reminder, will see themselves moving over the white lines (perhaps not doing the work to a previous standard) and maybe even hear the lane markers (get a low mark on a mid-term) but they can usually be relied upon to pull themselves back. But those students who are ‘asleep at the wheel’ will neither see the lines nor hear the warnings and that’s where we have a problem.

In terms of contribution and assessment, a student who is not showing up to class can’t get reports on what they’re failing, because they’ve submitted nothing to be marked. This is one of the reasons I try to chase students who don’t submit work, because otherwise they’ll get no feedback. If I’m using a collaborative mode to structure knowledge, students won’t realise what they’re missing out on if they just download the lecture notes – and they may not know because all of the white line warnings are contained in the activity that they’re not showing up for.

This places a great deal of importance on finding out why students aren’t even awake at the wheel, rather than just recording that they’ve skipped one set of lines, another, wow, they’re heading towards the embankment and I hope that the crash barrier holds.

Both on the road and in our classes, those crash barriers are methods of last resort. We have an ‘Unsatisfactory Academic Progress’ system that moves students to different level of reporting if they start systematically under performing – the only problem is that, to reach the UAP, you already have to be failing and, from any GPA calculation, even one fail can drag your record down for years. Enough fails to make UAP could mean that you will never, ever be perceived as a high performing student again, even if you completely turn your life around. So this crash barrier, which does work and has saved many students from disappearing off with fails, is something that we should not rely upon. Yes, people live through crash barrier collisions but a lot don’t and a lot get seriously injured.

Where are warning lines in our courses? We try to put one in within a week of starting, with full feedback and reporting in detail on one assessment well within the first 6 weeks of teaching. Personally, I try to put enough marking on the road that students can work out if they think that they are ready to be in that course (or to identify if they can get enough help to stay in), before they’ve been charged any money and it’s too late to withdraw.

I know a lot of people will read this and think “Hey, some people fail” and, yes, that’s perfectly true. Some people have so much energy built up that nothing will stop them and they’ll sail across the road and flip over the barrier. But, you know what? They had to start accelerating down that path somewhere. Someone had to give them the idea that what they were doing was ok – or they found themselves in an environment where that kind of bad reasoning made sense.

Someone may have seen them swerving all over the road, 10 miles back, and not known how to or had the ability to intervene. On the roads, being the domain of physics, I get that. How do you stop a swerving drunk without endangering yourself unless you have a squad of cars, trained officers, crash mats and a whole heap of water? That’s hard.

But the lines, markers and barriers in our courses aren’t dependent on physics, they are dependent upon effort, caring, attentiveness, good design and sound pedagogy. As always, I’m never saying that everyone should pass just for showing up but I am wondering aloud, mostly to myself, how I can construct something that keeps the crashes to a minimum and the self-corrections minor and effective.

Talk to the duck!

Posted: August 17, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, grand challenge, higher education, principles of design, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, time banking, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentI’ve had a funny day. Some confirmed acceptances for journals and an e-mail from a colleague regarding a collaboration that has stalled. When I set out to readjust my schedule to meet a sustainable pattern, I had a careful look at everything I needed to do but I overlooked one important thing: it’s easier to give the illusion of progress than it is to do certain things. For example, I can send you a ‘working on it’ e-mail every week or so and that takes me about a minute. Actually doing something could take 4-8 hours and that’s a very large amount of time!

So, today was a hard lesson because I’ve managed to keep almost all of the balls in the air, juggling furiously, as I trim down my load but this one hurts. Right now, someone probably thinks that I don’t care about their project – which isn’t true but it fell into the tough category of important things that needs a lot of work to get to the next stage. I’ve sent an apologetic and embarrassed e-mail to try and get this going again – with a high prioritisation of the actual work – but it’s probably too late.

The project in question went to a strange place – I was so concerned about letting the colleague down that I froze up every time I tried to do the work. Weird but true and, ultimately, harmful. But, ultimately, I didn’t do what I said I’d do and I’m not happy.

So how can I turn this difficult and unpleasant situation into something that I can learn from? Something that my students can benefit from?

Well, I can remember that my students, even though they come in at the start of the semester, often come in with overheads and burdens. Even if it’s not explicit course load, it’s things like their jobs, their family commitments, their financial burdens and their relationships. Sometimes it’s our fault because we don’t correctly and clearly specify prerequisites, assumed knowledge and other expectations – which imposes a learning burden on the student to go off and develop their own knowledge on their own time.

Whatever it is, this adds a new dimension to any discussion of time management from a student perspective: the clear identification of everything that has to be dealt with as well as their coursework. I’ve often noticed that, when you get students talking about things, that halfway through the conversation it’s quite likely that their eyes will light up as they realise their own problem while explaining things to other people.

There’s a practice in software engineering that is often referred to as “rubber ducking”. You put a rubber duck on a shelf and, when people are stuck on a problem, they go and talk to the duck and explain their problem. It’s amazing how often that this works – but it has to be encouraged and supported to work. There must be no shame in talking to the duck! (Bet you never thought that I’d say that!)

I’m still unhappy about the developments of today but, for the purposes of self-regulation and the development of mature time management, I’ve now identified a new phase of goal setting that makes sense in relation to students. The first step is to work out what you have to do before you do anything else, and this will help you to work out when you need to move your timelines backwards and forwards to accommodate your life.

This may actually be one of the best reasons for trying to manage your time better – because talking about what you have to do before you do any other assignments might just make you realise that you are going to struggle without some serious focus on your time.

Or, of course, it may not. But we can try. We can try with personal discussions, group discussions, collaborative goal setting – students sitting around saying “Oh yeah, I have that problem too! It’s going to take me two weeks to deal with that.” Maybe no-one will say anything.

We can but try! (And, if all else fails, I can give everyone a duck to talk to. 🙂 )

Group feedback, fast feedback, good feedback

Posted: August 16, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, collaboration, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, grand challenge, in the student's head, plagiarism, principles of design, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, vygotsky Leave a commentWe had the “first cut” poster presentation today in my new course. Having had the students present their pitches the previous week, this week was the time to show the first layout – put up your poster and let it speak for itself.

The results were, not all that surprisingly, very, very good. Everyone had something to show, a data story to tell and some images and graphs that told the story. What was most beneficial though was the open feedback environment, where everyone learned something from the comments on their presentation. One of my students, who had barely slept for days and was highly stressed, got some really useful advice that has given him a great way forward – and the ability to go to bed tonight with the knowledge that he has a good path forward for the next two weeks.

Working as a group, we could agree as a group, discuss and disagree, suggest, counter-suggest, develop and enhance. My role in all of this is partially as a ‘semi-expert’ but also as a facilitator. Keep the whole thing moving, keep it to time, make sure that everyone gets a good opportunity to show their work and give and receive feedback.

The students all write down their key feedback, which is scanned as a whole and put on the website so that any good points that went to anyone can now be used by anyone in the group. The feedback is timely, personal and relevant. Everyone feels that these sessions are useful and the work produced reflects the advantages. But everyone talks to everyone else – it’s compulsory. Come to the session, listen and then share your thoughts.

This, of course, reveals one of my key design approaches: collaboration is ok and there is no competitiveness. Read anything about the grand challenges and you keep seeing the word ‘community’ through it. Solid and open communities, where real and effective sharing happens, aren’t formed in highly competitive spaces. Because the students have unique projects, they can share ideas, references and even analysis techniques without plagiarism worries – because they can attribute without the risk of copying. Because there is no curve grading, helping someone else isn’t holding you back.

Because of this, we have already had two informal workshop groups form to address issues of analysis and software, where knowledge passes from person to person. Before today’s first cut presentation, a group was sitting outside, making suggestions and helping each other out – to achieve some excellent first cut results.

Yes, it’s a small group so, being me, now I’m worrying about how I would scale this up, how I would take this out to a large first-year class, how I would get it to a school group. This groups need careful facilitation and the benefit of inter-group communication is derived from everyone in the group having a voice. The number of interactions scale with the square of the group size, so there’s a finite limit to how many people I can have in the group and fit it into a two-hour practical session. If I split a larger class into sub-groups, I lose the advantage of everyone see in everyone else’s work.

But this can be solved, potentially with modern “e-” techniques, or a different approach to preparation, although I can’t quite see it yet. There’s a part of me that thinks “Ask these students how they would approach it”, because they have viewpoints and experience in this which complements mine.

Every week that goes by, I wonder if we will keep improving, and keep rewarding the (to be honest) risk that we’re taking in running a small course like this in leaner times. And, every week, the answer is a resounding “yes”!

Here’s to next week!

The Key Difference (or so it appears): Do You Love Teaching?

Posted: August 12, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, blogging, collaboration, community, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, higher education, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, workload 3 CommentsI wander around fair bit for work. (I make it sound more impressive than that but the truth is that I end up in lots of different places to work on my many projects and sometimes the movement, although purposeful, is more Brownian than not – due to life.) I’ve had a chance to talk to a lot of people who teach – some of whom are putting vast amounts of effort into it and some of whom aren’t.

The key difference, unsurprisingly, is generally the passion behind it. We see this in our students. They will spend days working on a Minecraft construction to simulate an Arithmetic and Logic Unit, but won’t always put in the two hours to write 20 lines of C++ code. They will write 20,000 words on their blog but can’t give you a 1,000 word summary.

We put effort into the things that we are interested in. Sure, if we’re really responsible and have self-regulation nailed, then we can do things that we’re not interested in, or actively dislike, but it’s never really going to have the same level of effort or commitment.

Passion (or the love of something) is crucial. Some days I have so much to say on the blog that I end up with 4-5 days stocked up in the queue. Some days I struggle to come up with the daily post or, as yesterday, I just run out of time to hit the 4am post cycle because I am doing other things that I am passionate about. Today, of course, the actual deadline timer is running and it seems to have made me think – now I’m passionate and now you’ll get something worth reading. If I’d stayed up until after my guests had left last night, written just anything to meet the deadline? It wouldn’t be anywhere near my best work.

Passion is crucial.

Which brings me to teaching. I know a lot of academics – some who are research/teaching/admin, some research only, some teaching/admin and… well, you get the picture. The majority are the ‘3-in-1’ academics and, in many regards, looking at their student evaluations and performance metrics will not tell you anything about them as a teacher that you can’t learn by sitting down with them and talking about their teaching. It is hard to shut me up about my courses and my students, the things I’m trying, the things I’m thinking of adopting, the other areas I’m looking at, the impact of what other Unis and people are doing, the impact of reports. I am a (junior) scholar in the discipline of learning and teaching and I really, really love teaching. For me, putting effort into it is inevitable, to a great extent.

Then I talk to colleagues who really just want to do their research and be left alone. Everything else is a drag on their research. Administration will get the minimum effort, if it’s done. Teaching is something that you have to do and, if the students don’t get it, then it’s their fault. What is so weird about this is that these people are, in the vast majority, excellent scholars in their own discipline. They research and read heavily, they are aware of what every other researcher is doing in this area, they know if their work has a chance for publication or grants. Having these skills, they then divide the world into ‘places where I have to scholarly’ and ‘places where I can phone it in’. (Not all researchers are like this, I’m talking about the ones who consider anything other than research beneath them.)

What a shame! What a terrible missed opportunity for both these people who should be more aware of the issues of learning and teaching, and for the students who could be learning so much more from them? But when you actually talk to these academics, some of them just don’t liked teaching, they don’t see the point of putting effort into it or (in some cases) they just don’t know what to do and how to improve so they hunker down and try to let it all slide around them.

Part of this is the selective memory that we have of ourselves as students. I’m lucky – I was terrible. I was fortunate enough to be aware and mature enough as I reconstructed myself as a good student to see the transformative process in action. A lot of my peers are happy to apply rules to students that they wouldn’t (or don’t ) apply to themselves now or in the past, such as:

“I’m an academic who doesn’t like teaching, despite being told that it’s part of my job, so I’ll do the minimum required – or less on some occasions. You, however, are a student who doesn’t like the sub-standard learning experiences that my indifference brings you but I’m telling you to do it, so just do it or I’ll fail you.”

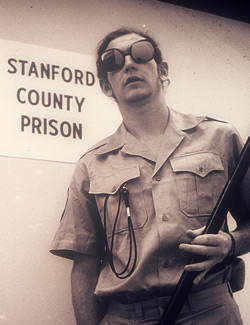

This isn’t just asymmetrical, this is bordering on the Stanford Prison Experiment, an arbitrary assignation of roles that leads to destructive power-derived behaviour. But, if course, if you don’t enjoy doing something then there are going to be issues.

Have we actually ever asked people these key questions as a general investigation? “Do you like teaching?” “What do you enjoy about teaching?” “What can we do to make you enjoy teaching more?” Would this muddy the water or clear the air? Would this earth our non-teaching teachers and fire them up?

Even where people run vanity courses (very small scale, research-focused courses design to cherry pick the good students) they are still often disappointed because, even where you can muster the passion to teach, if you don’t really understand how to teach or what you need to do to build a good learning experience, then you end up with these ‘good’ students in this ‘enjoyable’ course failing, complaining, dropping out and, in more analogous terms, kicking your puppy. You will now like teaching even less!

It’s blindingly obvious that some people don’t like teaching but, much as we wouldn’t stand out the front of a class and yell “PASS, IDIOTS!”, I’m looking for other good examples where we start to ask people why they don’t want to do it, what they’re worried about, why they don’t respect it and how we can get them more involved in the L&T community.

Let’s face it, when you love teaching, the worst day with the students is still a pretty good day. It would be nice to share this joy further.