Student Reflections – The End of Semester Process Report

Posted: June 27, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, education, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools Leave a commentI’ve mentioned before that I have two process awareness reports in one of my first-year courses. One comes just after the monster “Library” prac, and one is right at the end of the course. These encourage the students to reflect on their assignment work and think about their software development process. I’ve just finished marking the final one and, as last year, it’s a predominantly positive and rewarding experience.

When faced with 2-4 pages of text to produce, most of my students sit down and write several, fairly densely packed pages telling me about the things that they’ve discovered along the way: lessons learned, pit traps avoided and (interestingly) the holes that they did fall into. It’s rare that I get cynical replies and for this course, from over 100 responses, I think that I had about 5 disappointing ones.

The disappointing ones included ones that posted about how I had to give them marks for something that was rubbish (uh, no I didn’t, read the assignment spec and the forum carefully), ones that were scrawled together in about a minute and said nothing, and the ones that were the outpourings of someone who wasn’t really happy with where they were, rather than something I could easily fix. Let’s move on from these.

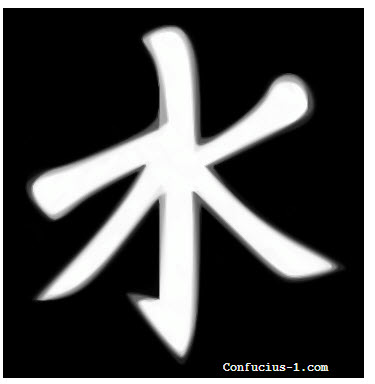

I want to talk about the ones who had crafted beautiful diagrams where they proudly displayed their software process. The ones who shared great ideas about how to help students in the next offering. The ones who shared the links that they found useful with me, in case other students would like them. The ones who were quietly proud of mastering their areas of difficulty and welcomed the opportunity to tell someone about it. The one who used this quote from Confucius:

“A man without distant care must have near sorrow”

(人无远虑 必有近忧)

To explain why you had to look into the future when you did software design – don’t leave your assignments to the last minute, he was saying, look ahead! (I am, obviously, going to use that for teaching next semester!)

Overall, I find these reports to be a resolutely uplifting experience. The vast majority of my students have learnt what I wanted them to learn and have improved their professional skills but, as well, a large number of them have realised that the assignments, together with the lectures, develop their knowledge. Here is one of my favourite student quotes about the assignments themselves, which tells me that we’re starting to get the design right:

The real payoff was towards the end of the assignment. Often it would be possible to “just type code” and earn at least half the marks fairly easily. However there was always a more complex final-part to the assignment, one that I could not complete unless I approached it in a systematic, well thought out way. The assignments made it easy to see that a program of any real complexity would be nearly impossible to build without a well-defined design.

But students were also thinking about how they were going to take more general lessons out of this. Here’s another quote I like:

Three improvements that I am aiming to take on board for future subjects are: putting together a study timetable early on in the game; taking the time to read and understand the problem I’ve been given; and put enough time aside to produce a concise design which includes testing strategies.

The exam for this course has just been held and we’re assembling the final marks for inspection on Friday, which will tell us how this new offering has gone. But, at this stage, I have an incredibly valuable resource of student feedback to draw on when I have to do any minor adjustments to make this course better for the next offering.

From a load perspective, yes, having two essays in an otherwise computationally based course does put load on the lecturer/marker but I am very happy to pay that price. It’s such a good way to find out what my students are thinking and, from a personal perspective, be a little more confident that my co-teaching staff and I are making a positive change in these students’ lives. Better still, by sharing comments from cohort to cohort, we provide an authenticity to the advice that I would be hard pressed to achieve.

I think that this course, the first one I’ve really designed from the ground up and I’m aware of how rare that opportunity is, is actually turning into something good. And that, unsurprisingly, makes me very happy.

Who Knew That the Slippery Slope Was Real?

Posted: June 26, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, blogging, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, motivation, plagiarism, resources, student perspective, thinking, time banking, tools, universal principles of design 1 CommentTake a look at this picture.

One thing you might have noticed, if you’ve looked carefully, is that this man appears to have had some reconstructive surgery on the right side of his face and there is a colour difference, which is slightly accentuated by the lack of beard stubble. What if I were to tell you that this man was offered the chance to have fake stubble tattooed onto that section and, when he declined because he felt strange about it, received a higher level of pressure and, in his words, guilt trip than for any other procedure during the extensive time he spent in hospital receiving skin grafts and burn treatments. Why was the doctor pressuring him?

Because he had already performed the tattooing remediation on two people and needed a third for the paper. In Dan’s words, again, the doctor was a fantastic physician, thoughtful, and he cared but he had a conflict of interest that meant that he moved to a different mode of behaviour. For me, I had to look a couple of times because the asymmetry that the doctor referred to is not that apparent at first glance. Yet the doctor felt compelled, by interests that were now Dan’s, to make Dan self-conscious about the perceived problem.

A friend on Facebook (thanks, Bill!) posted a link to an excellent article in Wired, entitled “Why We Lie, Cheat, Go to Prison and Eat Chocolate Cake” by Dan Ariely, the man pictured above. Dan is a professor of behavioural economics and psychology at Duke and his new book explores the reasons that we lie to each other. I was interested in this because I’m always looking for explanations of student behaviour and I want to understand their motivations. I know that my students will rationalise and do some strange things but, if I’m forewarned, maybe I can construct activities and courses in a way that heads this off at the pass.

There were several points of interest to me. The first was the question whether a cost/benefit analysis of dishonesty – do something bad, go to prison – actually has the effect that we intend. As Ariely points out, if you talk to the people who got caught, the long-term outcome of their actions was never something that they thought about. He also discusses the notion of someone taking small steps, a little each time, that move them from law abiding, for want of a better word, to dishonest. Rather than set out to do bad things in one giant leap, people tend to take small steps, rationalising each one, and after each step opening up a range of darker and darker options.

Welcome to the slippery slope – beloved argument of rubicose conservative politicians since time immemorial. Except that, in this case, it appears that the slop is piecewise composed on tiny little steps. Yes, each step requires a decision, so there isn’t the momentum that we commonly associate with the slope, but each step, in some sense, takes you to larger and larger steps away from the honest place from which you started.

Ariely discusses an experiment where he gave two groups designer sunglasses and told one group that they had the real thing, and the other that they had fakes, and then asked them to complete a test and then gave them a chance to cheat. The people who had been randomly assigned into the ‘fake sunglasses’ group cheated more than the others. Now there are many possible reasons for this. One of them is the idea that if you know that are signalling your status deceptively to the world, which is Ariely’s argument, you are in a mindset where you have taken a step towards dishonesty. Cheating a little more is an easier step. I can see many interpretations of this, because of the nature of the cheating which is in reporting how many questions you completed on the test, where self-esteem issues caused by being in the ‘fake’ group may lead to you over-promoting yourself in the reporting of your success on the quiz – but it’s still cheating. Ultimately, whatever is motivating people to take that step, the step appears to be easier if you are already inside the dishonest space, even to a degree.

[Note: Previous paragraph was edited slightly after initial publication due to terrible auto-correcting slipping by me. Thanks, Gary!]

Where does something like copying software or illicitly downloading music come into this? Does this constant reminder of your small, well-rationalised, step into low-level lawlessness have any impact on the other decisions that you make? It’s an interesting question because, according to the outline in Ariely’s sunglasses experiment, we would expect it to be more of a problem if the products became part of your projected image. We know that having developed a systematic technological solution for downloading is the first hurdle in terms of achieving downloads but is it also the first hurdle in making steadily less legitimate decisions? I actually have no idea but would be very interested to see some research in this area. I feel it’s too glib to assume a relationship, because it is so ‘slippery slope’ argument, but Ariely’s work now makes me wonder. Is it possible that, after downloading enough music or software, you could actually rationalise the theft of a car? Especially if you were only ‘borrowing’ it? (Personally, I doubt it because I think that there are several steps in between.) I don’t have a stake in this fight – I have a personal code for behaviour in this sphere that I can live with but I see some benefits in asking and trying to answer these questions from something other that personal experience.

Returning to the article, of particular interest to me was the discussion of an honour code, such as Princeton’s, where students sign a pledge. Ariely sees it as benefit as a reminder to people that is active for some time but, ultimately, would have little value over several years because, as we’ve already discussed, people rationalise in small increments over the short term rather than constructing long-term models where the pledge would make a difference. Sign a pledge in 2012 and it may just not have any impact on you by the middle of 2012, let alone at the end of 2015 when you’re trying to graduate. Potentially, at almost any cost.

In terms of ongoing reminders, and a signature on a piece of work saying (in effect) “I didn’t cheat”, Ariely asks what happens if you have to sign the honour clause after you’ve finished a test – well, if you’ve finished then any cheating has already occurred so the honour clause is useless then. If you remind people at the start of every assignment, every test, and get them to pledge at the beginning then this should have an impact – a halo effect to an extent, or a reminder of expectation that will make it harder for you to rationalise your dishonesty.

In our school we have an electronic submission system that require students to use to submit their assignments. It has boiler plate ‘anti-plagiarism’ text and you must accept the conditions to submit. However, this is your final act before submission and you have already finished the code, which falls immediately into the trap mentioned in the previous paragraph. Dan Ariely’s answers have made me think about how we can change this to make it more of an upfront reminder, rather than an ‘after the fact – oh it may be too late now’ auto-accept at the end of the activity. And, yes, reminder structures and behaviour modifiers in time banking are also being reviewed and added in the light of these new ideas.

The Wired Q&A is very interesting and covers a lot of ground but, realistically, I think I have to go and buy Dan Ariely’s book(s), prepare myself for some harsh reflection and thought, and plan for a long weekend of reading.

Time Banking and Plagiarism: Does “Soul Destroying” Have An Ethical Interpretation?

Posted: June 25, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, design, education, educational problem, feedback, higher education, in the student's head, learning, plagiarism, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, time banking, tools, work/life balance, workload 4 CommentsYesterday, I wrote a post on the 40 hour week, to give an industrial basis for the notion of time banking, and I talked about the impact of overwork. One of the things I said was:

The crunch is a common feature in many software production facilities and the ability to work such back-breaking and soul-destroying shifts is often seen as a badge of honour or mark of toughness. (Emphasis mine.)

Back-breaking is me being rather overly emphatic regarding the impact of work, although in manual industries workplace accidents caused by fatigue and overwork can and do break backs – and worse – on a regular basis.

But soul-destroying? Am I just saying that someone will perform their tasks as an automaton or zombie, or am I saying something more about the benefit of full cognitive function – the soul as an amalgam of empathy, conscience, consideration and social factors? Well, the answer is that, when I wrote it, I was talking about mindlessness and the removal of the ability to take joy in work, which is on the zombie scale, but as I’ve reflected on the readings more, I am now convinced that there is an ethical dimension to fatigue-related cognitive impairment that is important to talk about. Basically, the more tired you get, the more likely you are to function on the task itself and this can have some serious professional and ethical considerations. I’ll provide a basis for this throughout the rest of this post.

The paper I was discussing, on why Crunch Mode doesn’t work, listed many examples from industry and one very interesting paper from the military. The paper, which had a broken link in the Crunch mode paper, may be found here and is called “Sleep, Sleep Deprivation, and Human Performance in Continuous Operations” by Colonel Gregory Belenky. Now, for those who don’t know, in 1997 I was a commissioned Captain in the Royal Australian Armoured Corps (Reserve), on detachment to the Training Group to set up and pretty much implement a new form of Officer Training for Army Reserve officers in South Australia. Officer training is a very arduous process and places candidates, the few who make it in, under a lot of stress and does so quite deliberately. We have to have some idea that, if terrible things happen and we have to deploy a human being to a war zone, they have at least some chance of being able to function. I had been briefed on most of the issues discussed in Colonel Belenky’s paper but it was only recently that I read through the whole thing.

And, to me today as an educator (I resigned my commission years ago), there are still some very important lessons, guidelines and warnings for all of us involved in the education sector. So stay with me while I discuss some of Belenky’s terminology and background. The first term I want to introduce is droning: the loss of cognitive ability through lack of useful sleep. As Belenky puts in, in the context of US Army Ranger training:

…the candidates can put one foot in front of another and respond if challenged, but have difficulty grasping their situation or acting on their own initiative.

What was most interesting, and may surprise people who have never served with the military, is that the higher the rank, the less sleep people got – and the higher level the formation, the less sleep people got. A Brigadier in charge of a Brigade is going to, on average, get less sleep than the more junior officers in the Brigade and a lot less sleep than a private soldier in a squad. As an officer, my soldiers were fed before me, rested before me and a large part of my day-to-day concern was making sure that they were kept functioning. This keeps on going up the chain and, as you go further up, things get more complex. Sadly, the people shouldering the most complex cognitive functions with the most impact on the overall battlefield are also the people getting the least fuel for their continued cognitive endeavours. They are the most likely to be droning: going about their work in an uninspired way and not really understanding their situation. So here is more evidence from yet another place: lack of sleep and fatigue lead to bad outcomes.

One of the key issues Belenky talks about is the loss of situational awareness caused by the accumulated sleep debt, fatigue and overwork suffered by military personnel. He gives an example of an Artillery Fire Direction Centre – this is where requests for fire support (big guns firing large shells at locations some distance away) come to and the human plotters take your requests, transform them into instructions that can be given to the gunners and then firing starts. Let me give you a (to me) chilling extract from the report, which the Crunch Mode paper also quoted:

Throughout the 36 hours, their ability to accurately derive range, bearing, elevation, and charge was unimpaired. However, after circa 24 hours they stopped keeping up their situation map and stopped computing their pre-planned targets immediately upon receipt. They lost situational awareness; they lost their grasp of their place in the operation. They no longer knew where they were relative to friendly and enemy units. They no longer knew what they were firing at. Early in the simulation, when we called for simulated fire on a hospital, etc., the team would check the situation map, appreciate the nature of the target, and refuse the request. Later on in the simulation, without a current situation map, they would fire without hesitation regardless of the nature of the target. (All emphasis mine.)

Here, perhaps, is the first inkling of what I realised I meant by soul destroying. Yes, these soldiers are overworked to the point of droning and are now shuffling towards zombiedom. But, worse, they have no real idea of their place in the world and, perhaps most frighteningly, despite knowing that accidents happen when fire missions are requested and having direct experience of rejecting what would have resulted in accidental hospital strikes, these soldiers have moved to a point of function where the only thing that matters is doing the work and calling the task done. This is an ethical aspect because, from their previous actions, it is quite obvious that there was both a professional and ethical dimension to their job as the custodians of this incredibly destructive weaponry – deprive them of enough sleep and they calculate and fire, no longer having the cognitive ability (or perhaps the will) to be ethical in their delivery. (I realise a number of you will have choked on your coffee slightly at the discussion of military ethics but, in the majority of cases, modern military units have a strong ethical code, even to the point of providing a means for soldiers to refuse to obey illegal orders. Most failures of this system in the military can be traced to failures in a unit’s ethical climate or to undetected instability in the soldiers: much as in the rest of the world.)

The message, once again, is clear. Overwork, fatigue and sleeplessness reduce the ability to perform as you should. Belenky even notes that the ability to benefit from training quite clearly deteriorates as the fatigue levels increase. Work someone hard enough, or let them work themselves hard enough, and not only aren’t they productive, they can’t learn to do anything else.

The notion of situational awareness is important because it’s a measure of your sense of place, in an organisational sense, in a geographical sense, in a relative sense to the people around you and also in a social sense. Get tired enough and you might swear in front of your grandma because your social situational awareness is off. But it’s not just fatigue over time that can do this: overloading someone with enough complex tasks can stress cognitive ability to the point where similar losses of situational awareness can occur.

Helmet fire is a vivid description of what happens when you have too many tasks to do, under highly stressful situations, and you lose your situational awareness. If you are a military pilot flying on instruments alone, especially with low or zero visibility, then you have to follow a set of procedures, while regularly checking the instruments, in order to keep the plane flying correctly. If the number of tasks that you have to carry out gets too high, and you are facing the stress of effectively flying the plane visually blind, then your cognitive load limits will be exceeded and you are now experiencing helmet fire. You are now very unlikely to be making any competent contributions at all at this stage but, worse, you may lose your sense of what you were doing, where you are, what your intentions are, which other aircraft are around you: in other words, you lose situational awareness. At this point, you are now at a greatly increased risk of catastrophic accident.

To summarise, if someone gets tired, stressed or overworked enough, whether acutely or over time, their performance goes downhill, they lose their sense of place and they can’t learn. But what does this have to do with our students?

A while ago I posted thoughts on a triage system for plagiarists – allocating our resources to those students we have the most chance of bringing back to legitimate activity. I identified the three groups as: sloppy (unintentional) plagiarism, deliberate (but desperate and opportunistic) plagiarism and systematic cheating. I think that, from the framework above, we can now see exactly where the majority of my ‘opportunistic’ plagiarists are coming from: sleep-deprived, fatigued and (by their own hands or not) over-worked students losing their sense of place within the course and becoming focused only on the outcome. Here, the sense of place is not just geographical, it is their role in the social and formal contracts that they have entered into with lecturers, other students and their institution. Their place in the agreements for ethical behaviour in terms of doing the work yourself and submitting only that.

If professional soldiers who have received very large amounts of training can forget where there own forces are, sometimes to the tragic extent that they fire upon and destroy them, or become so cognitively impaired that they carry out the mission, and only the mission, with little of their usual professionalism or ethical concern, then it is easy to see how a student can become so task focussed that start to think about only ending the task, by any means, to reduce the cognitive load and to allow themselves to get the sleep that their body desperately needs.

As always, this does not excuse their actions if they resort to plagiarism and cheating – it explains them. It also provides yet more incentive for us to try and find ways to reach our students and help them form systems for planning and time management that brings them closer to the 40 hour ideal, that reduces the all-nighters and the caffeine binges, and that allows them to maintain full cognitive function as ethical, knowledgable and professional skill practitioners.

If we want our students to learn, it appears that (for at least some of them) we first have to help them to marshall their resources more wisely and keep their awareness of exactly where they are, what they are doing and, in a very meaningful sense, who they are.

The Internet is Forever

Posted: June 17, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, education, ethics, feedback, in the student's head, martha payne, reflection, student perspective, teaching approaches, thinking, tools 3 CommentsI realise that, between this blog and my other blog, I have a lot of ‘Nick” out there and there is always a chance that this may come back to haunt me. Well, given that I’m blogging under my own name and I have a vague idea of how this whole Internet thing works, I was ready for this possibility. What always amazes me, however, is when people don’t realise that the Internet is neither memoryless nor able to be reformatted through fiat, no matter how much you want it to be so. Anything that goes out into the Internet is, for most reasonable definitions, going to be there forever. Trying to act against the Internet… ooh… look up the Streisand Effect (Wikipedia link), if you don’t know what that is.

You may have read about the 9-year old Scottish school girl, Martha Payne, who was a bit disappointed about the range and quantity of school lunches she was receiving so, with her dad’s help and with her teachers’ knowledge, started a blog about it. You can read the whole story here (Wired link), with lots of tasty links, but the upshot is this:

- Martha wasn’t happy with her lunches because she wanted a bit more salad, to go along with the fried food, pizza and croquettes that made up her lunch.

- Very politely, and without a huge axe to grind, she started putting up pictures of her lunch.

- Within two weeks, unlimited salads had been added for children at her school. (This is just one of the improvements that took place over time.)

- To make better use of the positive feedback and publicity, after about 20 posts, she asked people who liked and followed her blog to donate money to a group that fund school meals in Africa.

- People started following her in greater numbers. Other students started sending in pictures of their lunches.

- People started writing about her.

- Martha was pulled out of class to be told that she could no longer photograph her school meals because of something that showed up in a newspaper.

This was one of the first school lunches that Martha posted about (picture from her blog). Yes, that’s the lot. The rabid sausage looking thing is potato covered in stuff. That is also MAXIMUM ALLOWABLE CORN.

At this point, the people who were directing the school, the Argyll and Bute Council, went ever so slightly mad and forgot everything I just told you about the Internet. Firstly, because it was now obvious to hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people that the A&B Council had censored a little girl from publishing pictures of her lunch. Secondly, because they posted an inaccurate and rather unpleasant statement about it, seeming to forget that everyone else could see what Martha had said and what the newspaper had said. This, of course, led to far more people knowing about the original blog than any other action that they could have taken. (I’m jealous, here, because Katrina had been following the blog before the shutdown!)

Thirdly, they forgot that the Internet is forever – that their statements, their actions to try and stop the tide from rolling, their questionable interpretation of events that might, if I were less generous, look both disingenuous and condescending (although I would never accuse the Argyll and Bute Council of such actions, obviously), these actions, and everyone’s reactions to them, are now out there. Archived. Indexed. Contextualised. Remembered.

Of course, the outcomes are unsurprising. After the Scottish Education Minister’s jaw was retrieved from the carpet, I can only imagine the speed with which the council was rung and asked exactly why they thought it a good idea to carry out their actions against a polite 9 year old girl. I note that the ban has now been lifted, the charity that Martha was working with now has so much money from donations that they can now build four kitchens to feed African school children, and some councillors have had a rather quick lesson in what globally instantaneous persistent communication means in the 21st century.

The issue here is that one girl looked at her plate, thought about it, spoke to some people and then,very politely, said “Please ;, may I have some more ;?” More salad then ensued! Food got healthier! The people at the school had responded sensibly. Children in Africa were getting more food! This was a giant win-win for the school and A&B Council – but somebody in the council couldn’t resist the urge to take a silly action in response to something that was no more Martha’a fault than the reporting of the Titanic caused the iceberg to drift into the sea lane.

Well done, Martha! Good luck with your continued photography of your increasingly pleasant, nutritious and delightful Scottish school lunches.

Time Banking IV: The Role of the Oracle

Posted: June 14, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, learning, measurement, principles of design, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, time banking 1 CommentI’ve never really gone into much detail on how I would make a system like Time Banking work. If a student can meet my requirements and submit their work early then, obviously, I have to provide some sort of mechanism that allows the students to know that my requirements have been met. The first option is that I mark everything as it comes in and then give the student their mark, allowing them to resubmit until they get 100%.

That’s not going to work, unfortunately, as, like so many people, I don’t have the time to mark every student’s assignment over and over again. I wait until all assignments have been submitted, review them as a group, mark them as a group and get the best use out of staying in the same contextual framework and working on the same assignments. If I took a piecemeal approach to marking, it would take me longer and, especially if the student still had some work to do, I could end up marking the same assignment 3,4, however many times and multiplying my load in an unsupportable way.

Now, of course I can come up with simple measures that the students can check for themselves. Of course, the problem we have here is setting something that a student can mis-measure as easily as they measure. If I say “You must have at least three pages for an essay” I risk getting three pages of rubbish or triple spaced 18 point print. It’s the same for any measure of quantity (number of words, number of citations, length of comments and so on) instead of quality. The problem is, once again, that if the students were capable of determining the quality of their own work and determining the effort and quality required to pass, they wouldn’t need time banking because their processes are already mature!

So I’m looking for an indicator of quality that a student can use to check their work and that costs me only (at most) a small amount of effort. In Computer Science, I can ask the students to test their work against a set of known inputs and then running their program to see what outputs we get. There is then the immediate problem of students hacking their code and just throwing it against the testing suite to see if they can fluke their way to a solution. So, even when I have an idea of how my oracle, my measure of meeting requirements, is going to work, there are still many implementation details to sort out.

Fortunately, to help me, I have over five years worth of student data through our automated assignment submission gateway where some assignments have an oracle, some have a detailed oracle, some have a limited oracle and some just say “Thanks for your submission.” The next stage in the design of the oracle is to go back and to see what impact the indications of progress and completeness had on the students. Most importantly, for me, is the indication of how many marks a student had to get in order to stop trying to make fresh submissions. If before the due date, did they always strive for 100%? If late, did they tend to stop at more than 50% of achieved marks, or more than 40% in the case of trying to avoid receiving a failing grade based on low assignment submission?

Are there significant and measurable differences between assignments with an oracle and those that have none (or a ‘stub’, so to speak)? I know what many people expect to find in the data, but now I have the data and I can go and interrogate that!

Every time that I have questions like this about the implementation, I have a large advantage in that I already have a large control body of data, before any attempts were made to introduce time banking. I can look at this to see what student behaviour is like and try to extract these elements and use them to assist students in smoothing out their application of effort and develop more mature time management approaches.

Now to see what the data actually says – I hope to post more on this particular aspect in the next week or so.

Time Banking II: We Are a Team

Posted: June 12, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, higher education, learning, measurement, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, time banking, tools, vygotsky Leave a commentIn between getting my camera ready copy together for ICER, and I’m still pumped that our paper got into ICER, I’ve been delving deep into the literature and the psychological and pedagogical background that I need to confirm before I go too much further with Time Banking. (I first mentioned this concept here. The term is already used in a general sense to talk about an exchange of services based on time as a currency. I use it here within the framework of student assignment submission.) I’m not just reading in CS Ed, of course, but across Ed, sociology, psychology and just about anywhere else where people have started to consider time as a manageable or tradable asset. I thought I’d take this post to outline some of the most important concepts behind it and provide some rationale for decisions that have already been made. I’ve already posted the guidelines for this, which can be distilled down to “not all events can be banked”, “additional load must be low”, “pragmatic limits apply”, “bad (cheating or gaming) behaviour is actively discouraged” and “it must integrate with our existing systems”.

Time/Bank currency design by Lawrence Weiner. Photo by Julieta Aranda. (Question for Nick – do I need something like this for my students?)

Our goal, of course, is to get students to think about their time management in a more holistic fashion and to start thinking about their future activities sometime sooner the 24 hours before the due date. Rather than students being receivers and storers of deadline, can we allow them to construct their own timelines, within a set of limits? (Ben-Ari, 1998, “Constructivism in Computer Science Education”, SIGCSE, although Ben-Ari referred to knowledge in this context and I’m adapting it to a knowledge of temporal requirements, which depends upon a mature assessment of the work involved and a sound knowledge of your own skill level.) The model that I am working with is effectively a team-based model, drawing on Dickinson and McIntyre’s 1997 work “Team Performance Assessment and Measurement: Theory, Methods and Applications.”, but where the team consists of a given student, my marking team and me. Ultimately our product is the submitted artefact and we are all trying to facilitate its timely production, but if I want students to be constructive and participative, rather than merely compliant and receptive, I have to involve them in the process. Dickinson and McIntyre identified seven roles in their model: orientation, leadership, monitoring, feedback, back-up (assisting/supporting), coordination and communication. Some of these roles are obviously mine, as the lecturer, such as orientation (establishing norms and keeping the group cohesive) and monitoring (observing performance and recognising correct contribution). However, a number of these can easily be shared between lecturer and student, although we must be clear as to who holds each role at a given time. In particular, if I hold onto deadlines and make them completely immutable then I have take the coordination role and handed over a very small fragment of that to the student. By holding onto that authority, whether it makes sense or not, I’m forcing the student into an authority-dependent mode.

(We could, of course, get into quite a discussion as to whether the benefit is primarily Piagiatien because we are connecting new experiences with established ideas, or Vygotskian because of the contact with the More Knowledgable Other and time spent in the Zone of Proximal Development. Let’s just say that either approach supports the importance of me working with a student in a more fluid and interactive manner than a more rigid and authoritarian relationship.)

Yes, I know, some deadlines are actually fixed and I accept that. I’m not saying that we abandon all deadlines or notion of immutability. What I am, however, saying is that we want our students to function in working teams, to collaborate, to produce good work, to know when to work harder earlier to make it easier for themselves later on. Rather than give them a tiny sandpit in which to play, I propose that we give them a larger space to work with. It’s still a space with edges, limits, defined acceptable behaviour – our monitoring and feedback roles are one of our most important contributions to our students after all – but it is a space in which a student can have more freedom of action and, for certain roles including coordination, start to construct their own successful framework for achievement.

Much as reading Vygotsky gives you useful information and theoretical background, without necessarily telling you how to teach, reading through all of these ideas doesn’t immediately give me a fully-formed implementation. This is why the guidelines were the first things I developed once I had some grip on the ideas, because I needed to place some pragmatic limits that would allow me to think about this within a teaching framework. The goal is to get students to use the process to improve their time management and process awareness and we need to set limits on possible behaviour to make sure that they are meeting the goal. “Hacks” to their own production process, such as those that allow them to legitimately reduce their development time (such as starting the work early, or going through an early prototype design) are the point of the exercise. “Hacks” that allow them to artificially generate extra hours in the time bank are not the point at all. So this places a requirement on the design to be robust and not susceptible to gaming, and on the orientation, leadership and monitoring roles as practiced by me and my staff. But it also requires the participants to enter into the spirit of it or choose not to participate, rather than attempting to undermine it or act to spite it.

The spontaneous generation of hours was something that I really wanted to avoid. When I sketched out my first solution, I realised that I had made the system far too complex by granting time credits immediately, when a ‘qualifying’ submission was made, and that later submissions required retraction of the original grant, followed by a subsequent addition operation. In fact, I had set up a potential race condition that made it much more difficult to guarantee that a student was using genuine extension credit time. The current solution? Students don’t get credit added to their account until a fixed point has passed, beyond which no further submissions can take place. This was the first of the pragmatic limits – there does exist a ‘no more submissions’ point but we are relatively elastic to that point. (It also stops students trying to use obtained credit for assignment X to try and hand up an improved version of X after the due date. We’re not being picky here but this isn’t the behaviour we want – we want students to think more than a week in advance because that is the skill that, if practised correctly, will really improve their time management.)

My first and my most immediate concern was that students may adapt to this ‘last hand-in barrier’ but our collected data doesn’t support this hypothesis, although there are some concerning subgroups that we are currently tearing apart to see if we can get more evidence on the small group of students who do seem to go to a final marks barrier that occurs after the main submission date.

I hope to write more on this over the next few days, discussing in more detail my support for requiring a ‘no more submissions’ point at all. As always, discussion is very welcome!

Last Lecture Blues

Posted: June 7, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, education, educational problem, feedback, games, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a commentI delivered the last lecture, technically the review and revision lecture, for my first year course today. As usual, when I’ve had a good group of students or a course I enjoy, the relief in having reduced my workload is minor compared to the realisation that another semester has come to an end and that this particular party is over.

Today’s lecture was optional but we still managed to get roughly 30% of the active class along. Questions were asked, questions were discussed, outline answers were given and then, although they all say and listened until I’d finished a few minutes late, they were all up and gone. The next time I’ll see most of them is at the exam, a few weeks from now. After that? It depends on what I teach. Some of these students I’ll run into over the years and we’ll actually get to know each other. Some may end up as my honours or post-graduate students. Some will walk out of the gates this semester and never return.

Now, hear me out, because I’m not complaining about it, but this is not the easiest job in the world. Done properly, education requires constant questioning, study, planning, implementing, listening, talking and, above all, dealing with the fact that you may see the best student you ever have for a maximum of 6 months. It is, however, a job that I love, a job that I have a passion for and, of course, in many ways it’s a calling more than a job.

One of the things I’ve had a chance to reflect on in this blog is how much I enjoy my job, while at the same time recognising how hard it is to do it well. Many times, the students I need to speak to most are those who contact me least, who up and fade away one day, leaving me wondering what happened to them.

At the end of the semester, it’s a good time to ask myself some core questions and see if I can give some good answers:

- Did I do the best job that I could do, given the resources (structures, curriculum, computers etc) that I had to work with?

- Did I actively seek out the students who needed help, rather than just waiting for people to contact me?

- Did I look for pitfalls before I ran into them?

- Did I look after the staff who were working with or for me, and mentor them correctly?

- Did I try to make everything that I worked with an awesome experience for my students?

This has been the busiest six months of my life and one of my joys has been walking into a lecture theatre, having written the course, knowing the material and losing myself in an hour of interactive, collaborative and enjoyable knowledge exchange with my students. Despite that, being so busy, sometimes I didn’t quite have the foresight that I should had had and my radar range was measured in days rather than weeks. Don’t get me wrong, everything got done, but I could have tried to locate troubled students more actively, and some minor pitfalls nearly got me.

However, I think that we still delivered a great course and I’m happy with 1, 4 and 5. I aimed for awesome and I think we hit it fairly often. 2 and 3 needed work but I’ve already started making the required changes to make this better.

On reflection, I’d give myself an 8ish/10 but, of course, that’s not enough. Overall, in the course, because of the excellent support from my co-lecturer and my teaching staff, the course itself I’d push up into the 9-pluses. I, however, should be up there as well and right now, I’m too busy.

So, it’s time for some rebalancing into the new semester. Some more structure for identifying problems students. Looking at things a little earlier. And aiming for an awesome 10/10 for my own performance next semester.

To all my students, past and present, it’s been fantastic. Best of luck with your exams!

Codes of Conduct: Being a Grown-Up.

Posted: May 31, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, education, educational problem, ethics, feedback, fiero, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, principles of design, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a commentI always hope that my students are functioning at a higher level, heading towards functional adulthood, to some extent. After all, if they need to go to the bathroom, they can usually manage that in a clean and tidy manner. They dress themselves. They can answer questions. So why do some of them act like children when it comes to good/bad behaviour?

I was reading Darlena’s blog post about one of Rafe Esquith’s books and she referred to Rafe’s referral to Kohlberg’s Six Levels of Moral Development, which I ‘quote-quote’ here:

- I do not want to get into trouble.

- I want a reward.

- I want to please someone.

- I always follow the rules.

- I am considerate of other people.

- I have a personal code of behaviour.

I’ve been talking around these points for a while, in terms of the Perry classifications of duality, multiplicity and commitment. What disappoints me the most is when I have to deal with students who are either trying not to get into trouble or only work for reward – and these are their prime motivations. There’s a world of difference between having students who do things because they have worked through everything we’ve talked about and decided to commit to that approach (step 6 in this scale) and those who only do it because they feel that they will get punished if they don’t.

I always say that I expect a lot of my students and, fairly early on, I do expect them to have formed a personal code of conduct. Yes, I expect them to be timely in their submissions, but because they understand that assignment placement is deliberate and assists them in knowledge formation. Yes, I expect them to not plagiarise or cheat, but because to do so deprives them of learning opportunities. I expect them not to talk in class because they don’t want to deprive other people of learning opportunities (which is a bit of points 5 and 6).

I press this point a lot. I say that I reward what they know, as long as it’s relevant, rather than punishing them for getting things wrong. I encourage them to participate, to be aware of other people, to interact and work with me to make the knowledge transfer more effective – to allow them to construct the mental frameworks required to produce the knowledge for themselves.

I really don’t think it’s good enough to say “Well, students always do X and what can you do?” I have a number of people in my classes who have discovered, to their mounting amazement, that I basically won’t accept behaviour that doesn’t meet reasonable standards. I mean what I say when I say things and I don’t change my mind just because someone asks me. I’m tough on plagiarism and cheating. I don’t let people bully me or other people. And, amazingly, I don’t see many of these behaviours in my class.

I encourage a constructive and positive approach for all of my students – but the basis of this is that they have to establish a personal code of conduct that I can work with. If they go down this path, then everything else tends to follow and we can go a fantastic educational journey together. If they’re still stuck, doing the minimum they can get away with, because they don’t want to get yelled at, then my first (and far more difficult) task is to reach them, try and get them to think beyond using this as their only motivator.

Now, of course, the golden rule is that if you want a student to do something, then giving marks for it is the best way to go – and that’s a technique I use, and I’ve discussed it before. But it’s never JUST the marks. There’s always reward in terms of scaffolding, or personal satisfaction, or insight. I want fiero! I also don’t want the students to do things just because I ask them to, because they want to please me. I have a middling amount of lecturing charisma but I’m always aware that I have to be content first/showmanship second. If I do that, then students are less likely to fall into the trap of trying to do things just because I ask them to.

I’m really not the kind of teacher who needs an apple on the desk. (I already have two iMacs and a MacBook Air. Ba-dum-*ting*)

Number 4 is one that I really want to steer people away from. Yes, rules should be followed – except where they shouldn’t. You may not know this but it is completely legitimate for a solider in the Australian Army to refuse to follow an illegal order. (Yes, it will probably not go very well but it’s still an option.) If a soldier, who is normally bound by the chain of command to follow orders, believes the order to be illegal (“No prisoners” being one of them) they don’t have to follow it. Australian soldiers are encouraged to exercise discretion and thought because that makes them better soldiers – they can fill in the blanks when the situation changes and potentially improve things. The price, of course, is that a thinker thinks.

Same for students. I want students who change the world, who make things better, who may occasionally walk on the grass to get to that bright new future even when the signs say ‘stay off the grass’. However, without a personal code of conduct, which rules you can bend or break are going to be fairly arbitrarily selected and are far more likely to have a selfish focus. We want rule bending in the face of sound ethics, not rationalisation.

As I said, it’s a lot to ask of students but, as I’ve always said, if I don’t ask for it, and tell people what I want, I can’t expect it and I certainly can’t build on it.

What Did You Learn From Higher Education?

Posted: May 27, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, curriculum, education, educational problem, feedback, higher education, reflection, work/life balance 1 CommentToday has been games day at my house. We’ve played some Arkham Horror and Lords of Waterdeep, one collaborative and one highly competitive board game, and it has been a lot of fun. It’s been the standard group of Australians around the table. Eight people, six with PhDs, and two currently studying for them. (That is, of course, not a serious comment on standard. A lot of my friends, including my wife, are University trained and have post-graduate qualifications.)

I was wondering what to talk about today and, at breakfast this morning, my wife suggested that I ask our guests what they got from going to University – what they learnt? (We gave them lunch and dinner so it wasn’t too much of an imposition. 🙂 )

My wife’s answer to the question was that she learnt to keep going, keep putting effort into her work to get something good out of a course. My answer was that I learnt that it was never over, even at the end of a degree – that you could always do something new, something different, change career. (Yes, we’re similar but not quite the same.)

When I asked my friends, I got a variety of responses, because we’d been playing games for over 8 hours and we’d had wine with dinner. One said that he was still learning, but that he thought it was more about the process than the output. One said that she learnt how to drink and keep up with men (I suspect this wasn’t her most serious answer). Another said that, although it sounded cynical, he thought it was often better to be convincing than right. One, who I work with closely, said that truly horrific educators cannot spoil kids if the kids are really keen. One said that he learnt programming.

The last answer got laughs from around the table, as did many of the answers – as did the question. There are always going to be a range of answers to a question like this: a person’s reaction to this question, especially when I told them was going to publish it, is generally going to be framed self-consciously. However, all of them are using the skills that they learnt in Higher Education and all of them at least started PhD studies, even if they hadn’t completed them yet. There is no doubt, in this group, that the University if a useful thing, even if particular instances are not fantastic exemplars of that.

But it’s an interesting question. What did you learn from your foray into higher ed, if you’ve done it. What do you think of when you think of higher education? If you’re going there, what are you expecting to learn? If you’ve never had any direct exposure, what do you think that people learn when they’re there?

The Confusing Message: Sourcing Student Feedback

Posted: May 26, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, education, educational problem, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, learning, measurement, MIKE, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a commentOnce, for a course which we shall label ‘an introduction to X and Y’, I saw some feedback from a student that went as follows. A single student, on the same feedback form, and in adjacent text boxes, gave these answers:

What do you like most about this course: the X

What would you like to see happen to improve the course: less X, more Y!

Now, of course, this not inherently contradictory but, honestly, it’s really hard to get the message here. You think that X is great but less useful than Y, although you like X more? You’re a secret masochist and you like to remove pleasure from your life?

As (almost) always, the problem here is that we these two questions, asked in adjacent text boxes, are asking completely different things. Survey construction is an art, a dark and mysterious art, and a well-constructed survey will probably not answer a question once, in one way. It will ask the same question in multiple ways, sometimes in the negative, to see if the “X” and “not ( not (X))” scores line up for each area of interest. This, of course, assumes that you have people who are willing to fill out long surveys and give you reliable answers. This is a big assumption. Most of the surveys that I work with have to fit into short time frames and are Likert-based with text boxes. Not quite yes/no tick/flick but not much more and very little opportunity for mutually interacting questions.

Our student experience surveys are about 10 questions long with two text boxes and are about the length that we can fit into the end of a lecture and have the majority of students fill out and return. From experience, if I construct larger surveys, or have special ‘survey-only’ sessions, I get poor participation. (Hey, I might just be doing it wrong. Tips and help in the comments, please!)

Of course, being Mr Measurement, I often measure things as side effects of the main activity. Today, I held a quiz in class and while everyone was writing away, I was actually getting a count of attendees because they were about to hand up cards for marking. This gives me an indicator of attendance and, as it happens, two weeks away from the end of the course, we’re still getting good attendance. (So, I’m happy.) I can also see how the students are doing with fundamental concepts so I can monitor that too.

I’m fascinated by what students think about their experience but I need to know what they need based on their performance, so that I can improve their performance without having to work out what they mean. The original example would give me no real insight into what to do and how to improve – so I can’t really do anything with any certainty. If the student had said “I love X but I feel that we spent too much time on it and it could be just as good with a little less.” then I know what I can do.

I also sometimes just ask for direct feedback in assignments, or in class, because then I’ll get the things that are really bugging or exciting people. That also gives me the ability to adapt to what I hear and ask more directed questions.

Student opinion and feedback can be a vital indicator of our teaching efficacy, assuming that we can find out what people think rather than just getting some short and glib answers to questions that don’t really probe in the right ways, where we never get a real indication of their thoughts. To do this requires us to form a relationship, to monitor, to show the value of feedback and to listen. Sadly, that takes a lot more work than throwing out a standard form once a semester, so it’s not surprising that it’s occasionally overlooked.