Loading the Dice: Show and Tell

Posted: September 6, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools Leave a commentI’ve been using a set of four six-sided dice to generate random numbers for one of my classes this year, generally to establish a presentation order or things like that. We’ve had a number of students getting the same number and so we have to have roll-offs. Now in this case, the most common number rolled so far has been in the range of 17-19 but we have only generated about 18-20 rolls so, while that’s a little high, it’s not high enough to arouse suspicion.

Today we rolled again, and one student wasn’t quite there yet so I did it with the rest of the class. Once again, 18 showed up a bit. This time I asked the class about it. Did that seem suspicious? Then I asked them to look at the dice.

Oh.

Only two of the dice are actually standard dice. One has the number five on every face. One has three sixes and three twos. The students have seen these dice numerous times and have never actually examined them – of course, I didn’t leave them lying around for them to examine but, despite one or two starting to think “Hey, that’s a bit weird”, nobody ever twigged to the loading.

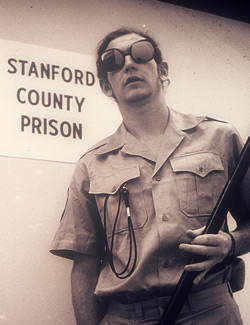

All of the dice in this picture are loaded through weight manipulation, rather than dot alteration. You can buy them for just about any purpose. Ah, Internet!

Having exposed this trick, to some amusement, the last student knocked on the door and I picked up the dice. He was then asked to roll for his position, with the rest of the class staying quiet. (Well, smirking.) He rolled something in 17-19, I forget what, and I wrote that up on the board. Then I asked him if it seemed high to him? On reflection, he said that these numbers all seemed pretty high, especially as the theoretical maximum was 24. I then asked if he’d like to inspect the dice.

He then did so, as I passed him the dice one at a time, and storing the inspected dice in my other hand. (Of course, as he peered at each die to see if it was altered, I quickly swapped one of the ‘real’ dice back into the position in my hand and, as the rest of the class watched and kept admirably quiet, I then forced a real die onto him. Magic is all about misdirection, after all.)

So, having inspected all of them, he was convinced that they were normal. I then plonked them down on the table and asked him to inspect them, to make sure. He lined them up, looked across the top face and, then, looked at the side. Light dawned. Loudly! What, of course, was so startling to him was that he had just inspected the dice and now they weren’t normal.

What was my point?

My students have just completed a project on data visualisation where they provided a static representation of a dataset. There is a main point to present, supported by static analysis and graphs, but the poster is fundamentally explanatory. The only room for exploration is provided by the poster producer and the reader is bound by the inherent limitations in what the producer has made available. Much as with our discussions of fallacies in argument from a recent tutorial, if information is presented poorly or you don’t get enough to go on, you can’t make a good decision.

Enter, the dice.

Because I deliberately kept the students away from them and never made a fuss about them, they assumed that they were normal dice. While the results were high, and suspicion was starting to creep in, I never gave them enough space to explore the dice and discern their true nature. Even today, while handing them to a student to inspect, I controlled the exploration and, by cherry picking and misdirection, managed to convey a false impression.

Now my students are moving into dynamic visualisation and they must prepare for sharing data in a way that can be explored by other people. While the students have a lot of control over who this exploration takes place, they must prepare for people’s inquisitiveness, their desire to assemble evidence and their tendency to want to try everything. They can’t rely upon hiding difficult pieces of data in their representation and they must be ready for users who want to keep exploring through the data in ways that weren’t originally foreseen. Now, in exploratory mode, they must prepare for people who want to try to collect enough evidence to determine if something is true or not, and to be able to interrogate the dataset accordingly.

Now I’m not saying that I believe that their static posters were produced badly, and I did require references to support statements, but the view presented was heavily controlled. They’ve now seen, in a simple analogue, how powerful that can be. Now, it’s time to break out of that mindset and create something that can be freely explored, letting their design guide the user to construct new things rather than to lead them down a particular path.

I can only hope that they’re exceed by this because I certainly am!!

Talk to the duck!

Posted: August 17, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, grand challenge, higher education, principles of design, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, time banking, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentI’ve had a funny day. Some confirmed acceptances for journals and an e-mail from a colleague regarding a collaboration that has stalled. When I set out to readjust my schedule to meet a sustainable pattern, I had a careful look at everything I needed to do but I overlooked one important thing: it’s easier to give the illusion of progress than it is to do certain things. For example, I can send you a ‘working on it’ e-mail every week or so and that takes me about a minute. Actually doing something could take 4-8 hours and that’s a very large amount of time!

So, today was a hard lesson because I’ve managed to keep almost all of the balls in the air, juggling furiously, as I trim down my load but this one hurts. Right now, someone probably thinks that I don’t care about their project – which isn’t true but it fell into the tough category of important things that needs a lot of work to get to the next stage. I’ve sent an apologetic and embarrassed e-mail to try and get this going again – with a high prioritisation of the actual work – but it’s probably too late.

The project in question went to a strange place – I was so concerned about letting the colleague down that I froze up every time I tried to do the work. Weird but true and, ultimately, harmful. But, ultimately, I didn’t do what I said I’d do and I’m not happy.

So how can I turn this difficult and unpleasant situation into something that I can learn from? Something that my students can benefit from?

Well, I can remember that my students, even though they come in at the start of the semester, often come in with overheads and burdens. Even if it’s not explicit course load, it’s things like their jobs, their family commitments, their financial burdens and their relationships. Sometimes it’s our fault because we don’t correctly and clearly specify prerequisites, assumed knowledge and other expectations – which imposes a learning burden on the student to go off and develop their own knowledge on their own time.

Whatever it is, this adds a new dimension to any discussion of time management from a student perspective: the clear identification of everything that has to be dealt with as well as their coursework. I’ve often noticed that, when you get students talking about things, that halfway through the conversation it’s quite likely that their eyes will light up as they realise their own problem while explaining things to other people.

There’s a practice in software engineering that is often referred to as “rubber ducking”. You put a rubber duck on a shelf and, when people are stuck on a problem, they go and talk to the duck and explain their problem. It’s amazing how often that this works – but it has to be encouraged and supported to work. There must be no shame in talking to the duck! (Bet you never thought that I’d say that!)

I’m still unhappy about the developments of today but, for the purposes of self-regulation and the development of mature time management, I’ve now identified a new phase of goal setting that makes sense in relation to students. The first step is to work out what you have to do before you do anything else, and this will help you to work out when you need to move your timelines backwards and forwards to accommodate your life.

This may actually be one of the best reasons for trying to manage your time better – because talking about what you have to do before you do any other assignments might just make you realise that you are going to struggle without some serious focus on your time.

Or, of course, it may not. But we can try. We can try with personal discussions, group discussions, collaborative goal setting – students sitting around saying “Oh yeah, I have that problem too! It’s going to take me two weeks to deal with that.” Maybe no-one will say anything.

We can but try! (And, if all else fails, I can give everyone a duck to talk to. 🙂 )

Group feedback, fast feedback, good feedback

Posted: August 16, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, collaboration, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, grand challenge, in the student's head, plagiarism, principles of design, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, vygotsky Leave a commentWe had the “first cut” poster presentation today in my new course. Having had the students present their pitches the previous week, this week was the time to show the first layout – put up your poster and let it speak for itself.

The results were, not all that surprisingly, very, very good. Everyone had something to show, a data story to tell and some images and graphs that told the story. What was most beneficial though was the open feedback environment, where everyone learned something from the comments on their presentation. One of my students, who had barely slept for days and was highly stressed, got some really useful advice that has given him a great way forward – and the ability to go to bed tonight with the knowledge that he has a good path forward for the next two weeks.

Working as a group, we could agree as a group, discuss and disagree, suggest, counter-suggest, develop and enhance. My role in all of this is partially as a ‘semi-expert’ but also as a facilitator. Keep the whole thing moving, keep it to time, make sure that everyone gets a good opportunity to show their work and give and receive feedback.

The students all write down their key feedback, which is scanned as a whole and put on the website so that any good points that went to anyone can now be used by anyone in the group. The feedback is timely, personal and relevant. Everyone feels that these sessions are useful and the work produced reflects the advantages. But everyone talks to everyone else – it’s compulsory. Come to the session, listen and then share your thoughts.

This, of course, reveals one of my key design approaches: collaboration is ok and there is no competitiveness. Read anything about the grand challenges and you keep seeing the word ‘community’ through it. Solid and open communities, where real and effective sharing happens, aren’t formed in highly competitive spaces. Because the students have unique projects, they can share ideas, references and even analysis techniques without plagiarism worries – because they can attribute without the risk of copying. Because there is no curve grading, helping someone else isn’t holding you back.

Because of this, we have already had two informal workshop groups form to address issues of analysis and software, where knowledge passes from person to person. Before today’s first cut presentation, a group was sitting outside, making suggestions and helping each other out – to achieve some excellent first cut results.

Yes, it’s a small group so, being me, now I’m worrying about how I would scale this up, how I would take this out to a large first-year class, how I would get it to a school group. This groups need careful facilitation and the benefit of inter-group communication is derived from everyone in the group having a voice. The number of interactions scale with the square of the group size, so there’s a finite limit to how many people I can have in the group and fit it into a two-hour practical session. If I split a larger class into sub-groups, I lose the advantage of everyone see in everyone else’s work.

But this can be solved, potentially with modern “e-” techniques, or a different approach to preparation, although I can’t quite see it yet. There’s a part of me that thinks “Ask these students how they would approach it”, because they have viewpoints and experience in this which complements mine.

Every week that goes by, I wonder if we will keep improving, and keep rewarding the (to be honest) risk that we’re taking in running a small course like this in leaner times. And, every week, the answer is a resounding “yes”!

Here’s to next week!

Putting it all together – discussing curriculum with students

Posted: August 15, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, collaboration, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, popeye, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, wimpy, workload Leave a commentOne of the nice things about my new grand challenges course is that the lecture slots are a pre-reading based discussion of the grand challenges in my discipline (Computer Science), based on the National Science Foundation’s Taskforce report. Talking through this with students allows us to identify the strengths of the document and, perhaps more interestingly, some of its shortfalls. For example, there is much discussion on inter-disciplinary and international collaboration as being vital, followed by statements along the lines of “We must regain the ascendancy in the discipline that we invented!” because the NSF is, first and foremost, a US-funded organisation. There’s talk about providing the funds for sustainability and then identifying the NSF as the organisation giving the money, and hence calling the shots.

The areas of challenge are clearly laid out, as are the often conflicting issues surrounding the administration of these kinds of initiative. Too often, we see people talking about some amazing international initiative – only to see it fail because nobody wants to go first, or no country/government wants to put money up that other people can draw on until everyone does it at the same time.

In essence, this is a timing and trust problem. If we may quote Wimpy from the Popeye cartoons:

The NSF document lays bare the problem we always have: those who have the hamburgers are happy to talk about sharing the meal but there are bills to be paid. The person who owns the hamburger stand is going to have words with you if you give everything away with nothing to show in return except a promise of payment on Tuesday.

Having covered what the NSF considered important in terms of preparing us for the heavily computerised and computational future, my students finished with a discussion of educational issues and virtual organisations. The educational issues were extremely interesting because, having looked at the NSF Taskforce report, we then looked at the ACM/IEEE 2013 Computer Science Strawman curriculum to see how many areas overlapped with the task force report. Then we looked at the current curriculum of our school, which is undergoing review at the moment but was last updated for the 2008 ACM/IEEE Curriculum.

What was pleasing was, rom the range of students, how many of the areas were being addressed throughout our course and how much overlap there was between the highlighted areas of the NSF Report and the Strawman. However, one of the key issues from the task force report was the notion of greater depth and breadth – an incredible challenge in the time-constrained curriculum implementations of the 21st century. Adding a new Knowledge Area (KA) to the Strawman of ‘Platform Dependant Computing’ reflects the rise of the embedded and mobile device yet, as the Strawman authors immediately admit, we start to make it harder and harder to fit everything into one course. Combine this with the NSF requirement for greater breadth, including scientific and mathematical aspects that have traditionally been outside of Computing, and their parallel requirement for the development of depth… and it’s not easy.

The lecture slot where we discussed this had no specific outcomes associated with it – it was a place to discuss the issues arising but also to explain to the students why their curriculum looks the way that it does. Yes, we’d love to bring in Aspect X but where does it fit? My GC students were looking at the Ethics aspects of the Strawman and wondered if we could fit Ethics into its own 3-unit course. (I suspect that’s at least partially my influence although I certainly didn’t suggest anything along these lines.) “That’s fine,” I said, “But what do we lose?”

In my discussions with these students, they’ve identified one of the core reasons that we changed teaching languages, but I’ve also been able to talk to them about how we think as we construct courses – they’ve also started to see the many drivers that we consider, which I believe helps them in working out how to give feedback that is the most useful form for us to turn their needs and wants into improvements or developments in the course. I don’t expect the students to understand the details and practice of pedagogy but, unless I given them a good framework, it’s going to be hard for them to communicate with me in a way that leads most directly to an improved result for both of us.

I’ve really enjoyed this process of discussion and it’s been highly rewarding, again I hope for both sides of the group, to be able to discuss things without the usual level of reactive and (often) selfish thinking that characterises these exchanges. I hope this means that we’re on the right track for this course and this program.

In A Student’s Head – Mine From 26 Years Ago

Posted: August 11, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, ALTA, blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, games, higher education, in the student's head, principles of design, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentI attended an Australian Council of Deans of ICT Learning and Teaching Academy event run by Elena Sitnikova from the University of South Australia. Elena is one of the (my fellow?) Fellows in ALTA and works in Cyber Security and Forensic Computing. Today’s focus was on discussing the issues in ICT education in Australia, based on the many surveys that have been run, presenting some early work on learning and teaching grants and providing workshops on “Improving learning and teaching practice in ICT Education” and “Developing Teamwork that Works!”. The day was great (with lots of familiar faces presenting a range of interesting topics) and the first workshop was run by Sue Wright, graduate school in Education, University of Melbourne. This, as always, was a highly rewarding event because Sue forced me to go back and think about myself as a student.

This is a very powerful technique and I’m going to outline it here, for those who haven’t done it for a while. Drawing on Bordieu’s ideas on social and cultural capital, Sue asked us to list our non-financial social assets and disadvantages when we first came to University. This included things like:

- Access to resources

- Physical appearance

- Educational background

- Life experiences

- Intellect and orientation to study

- Group membership

- Accent

- Anything else!

When you think about yourself in this way, you suddenly have to think about not only what you had, but what you didn’t have. What helped you stay in class?What meant that you didn’t show up? From a personal perspective, I had good friends and a great tan but I had very little life experience, a very poor study ethic, no real sense of consequences and a very poor support network in an academic sense. It really brought home how lucky I was to have a group of friends that kept me coming to University. Of course, in those pre-on-line days, you had to come to Uni to see your friends, so that was a good reason to keep people on campus – it allowed for you to learn things by bumping into a people, which I like to refer to as “Brownian Communication”.

This exercise made me think about my transition to being a successful student. In my case, it took more than one degree and a great deal more life experience before I was ready to come back and actually succeed. To be honest, if you looked at my base degree, you’d never have thought that I would make it all the way to a PhD and, yet, here I am, on a path where I am making a solid and positive difference.

Sue then reminded people of Hofstede’s work on cultural dimensions – power distance, individualism versus collectivism, and uncertainty avoidance. How do students work – do they need a large ‘respect gap’ between student and teacher? Do they put family before their own study? Do they do anything rather than explore the uncertain? It’s always worth remembering that, where “the other” exists for us, we exist as “the other” reciprocally. While it’s comfortable as white, culturally English and English speaking people to assume that “the other” is transgressing with respect to our ‘dominant’ culture, we may be asking people to do something that is incredibly uncomfortable and goes far beyond learning another language.

One of the workshop participants was born and grew up in Korea and he made the observation that, when he was growing up, the teacher was held at the same level of the King and your father – and you don’t question the King or your father! He also noted that, on occasion, ‘respect’ had to be directed towards teachers that they did not actually respect. He had one bad teacher and, in that class, the students asked no questions and just let the teacher talk. As someone who works within a very small power distance relationship with y students, I have almost never felt disrespected by anything that my students do, unless they are actively trying to be rude and disrespectful. If I have nobody following, or asking questions, then I always start to wonder if I’ve been tuned out and they are listening to the music in their heads. (Or on their iPhones, as it is the 21st Century!)

Australia is a low power distance/high individualism culture with a focus on the short-term in many respects (as evidence by profit and loss quarterly focus and, to be frank, recent political developments). Bringing people from a high PD/high collectivism culture, such as some of those found in South East Asia, will need some sort of management to ensure that we don’t accidentally split the class. It’s not enough to just say “These students do X” because we know that we can, with the right approach, integrate our student body. But it does take work.

As always, working with Sue (you never just listen to Sue, she always gets you working) was a very rewarding and reflective activity. I spent 20 minutes trying to learn enough about a colleague from UniSA, Sang, that I could answer questions about his life. While I was doing this, he was trying to become Nick. What emerged from this was how amazingly similar we actually are – different Unis, different degrees, different focus, one Anglo-origin, one Korean-origin – and it took us quite a while to find things where we were really so different that we could talk about the challenges if we had to take on each other’s lives.

It was great to see most of the Fellows again but, looking around a large room that wasn’t full to the brim, it reminded me that we are often talking to those people who already believe that what we’re doing is the right thing. The people that really needed to be here were the people who weren’t in the room.

I’m still thinking about how we can continue our work to reach out and bring more people into this very, very rewarding community.

Silk Purses and Pig’s Ears

Posted: August 6, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, winemaking 2 CommentsThere’s an old saying “You can’t make a silk purse out of a pig’s (or sow’s) ear”. It’s the old chestnut that you can’t make something good out of something bad and, when you’re talking about bad grapes or rotten wood, then it has some validity (but even then, not much, as I’ll note later). When it’s applied to people, for any of a large range of reasons, it tends to become an excuse to give up on people or a reason why a lack of success on somebody’s part cannot be traced back to you.

I’m doing a lot of reading in the medical and general ethics as part of my preparation for one of the Grand Challenge lectures. The usual names and experiments show up, of course, when you start looking at questionable or non-existent ethics: Milgram, the Nazis, Stanford Prison Experiment, Unit 731, Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, Little Albert and David Reimer. What starts to come through from this study is that, in many of these cases, the people being experimented upon have reached a point in the experimenter’s eyes where they are not people, but merely ‘subjects’ – and all too often in the feudal sense as serfs, without rights or ability to challenge what is happening.

But even where the intention is, ostensibly, therapeutic, there is always the question of who is at fault when a therapeutic procedure fails to succeed. In the case of surgical malpractice or negligence, the cause is clear – the surgeon or a member of her or his team at some point made a poor decision or acted incorrectly and thus the fault lies with them. I have been reading up on early psychiatric techniques, as these are full of stories of questionable approaches that have been later discredited, and it is interesting in how easy it is for some practitioners to wash their hands of their subject because they had a lack of “good previous personality” – you can’t make a silk purse out of a pig’s ear. In many cases, with this damning judgement, people with psychiatric problems would often be shunted off to the wards of mental hospitals.

I refer, in this case, to William Sargant (1907-1988), a British psychiatrist who had an ‘evangelical zeal’ for psychosurgery, deep sleep treatment, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and insulin shock therapy. Sargant used narcosis extensively, drug induced deep sleep, as he could then carry out a range of procedures on the semi- and unconscious patients that they would have possibly learned to dread if they have received them while conscious. Sargant believed that anyone with psychological problems should be treated early and intensively with all available methods and, where possible, all these methods should be combined and applied as necessary. I am not a psychiatrist and I leave it to the psychiatric and psychotherapy community to assess the efficacy and suitability of Sargant’s methods (they disavow them, for the most part, for what it’s worth) but I mention him here because he did not regard failures as being his fault. It is his words that I am quoting in the previous paragraph. People for whom his radical, often discredited, zealous and occasionally lethal experimentation did not work were their own problem because they lacked a “good previous personality”. You cannot, as he was often quoted to have said, make a silk purse out of a pig’s ear.

How often I have heard similar ideas being expressed within the halls of academia and the corridors of schools. How easy a thing it is to say. Well, one might say, we’ve done all that we can with this particular pupil, but… They’re just not very bright. They daydream in class rather than filling out their worksheets. They sleep at their desks. They never do the reading. They show up too late. They won’t hang around after class. They ask too many questions. They don’t ask enough questions. They won’t use a pencil. They only use a pencil. They talk back. They don’t talk. They think they’re so special. Their kind never amounts to anything. They’re just like their parents. They’re just like the rest of them.

“We’ve done all we can but you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.”

As always, we can look at each and every one of those problems and ask “Why?” and, maybe, we’ll get an answer that we can do something about. I realise that resources and time are both scarce commodities but, even if we can’t offer these students the pastoral care that they need (and most of those issues listed above are more likely to be social/behavioural than academic anyway), let us stop pretending that we can walk away, blameless, as Sargant did because these students are fundamentally unsalvageable.

Yeah, sorry, I know that I go on about this but it’s really important to keep on hammering away at this point, every time that I see how my own students could be exposed to it. They need to know that the man that they’re working with expects them to do things but that he understands how much of his job is turning complex things into knowledge forms that they can work with – even if all he does is start the process and then he hands it to them to finish.

Do you want to know how to make great wine? Start with really, really good grapes and then don’t mess it up. Want to know how to make good wine? Well, as someone who used to be a reasonable wine maker, you can give me just about anything – good fruit, ok fruit, bad fruit, mouldy fruit – and I could turn it into wine that you would happily drink. I hasten to point out that I worked for good wineries and the vast quantity of what I did was making good wine from good grapes, but there were always the moments where you had something that, from someone else’s lack of care or inattention, had got into a difficult spot. Understanding the chemical processes, the nature of wine and working out how we could recover the wine? That is a challenge. It’s time consuming, it takes effort, it takes a great deal of scholarly knowledge and you have to try things to see if they work.

In the case of wine, while I could produce perfectly reasonable wine from bad grapes, simple chemistry prevents me from leaving in enough of the components that could make a wine great. That is because wine recovery is all about taking bad things out. I see our challenge in education as very different. When we find someone who is need of our help, it is what we can put in that changes them. Because we are adding, mentoring, assisting and developing, we are not under the same restrictions as we are with wine – starting from anywhere, I should be able to help someone to become a great someone.

The pig’s ears are safe because I think that we can make silk purses out of just about anything that we set our minds to.

Grand Challenges Course: Great (early) progress on the project work.

Posted: August 2, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: Csíkszentmihályi, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, flow, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, vygotsky, Zone of proximal development Leave a commentWhile I’ve been talking about the project work in my new “Grand Challenge”-based course a lot, I’ve also identified a degree of, for want of a better word, fearfulness on the part of the students. Given that their first project is a large poster with a visualisation of some interesting data, which they have to locate and analyse, and that these are mostly Computer Science students with no visualisation experience, they are understandably slightly concerned. We’ve been having great discussions and lots of contributions but next week is their first pitch and, suddenly, they need a project theme.

I’ve provided a fair bit of guidance for the project pitch, and I reproduce it here in case you’re interested:

Project 1: First Deliverable, the Pitch

Due 2pm, Wednesday, the 8th of August Because group feedback is such an important part of this project, you must have your pitch ready to present for this session and have the best pitch ready that you can. Allocate at least 10 hours to give you enough time to do a good job.

What is the pitch?

A pitch is generally an introduction of a product or service to an audience who knows nothing about it but is often used to expand knowledge and provide a detailed description of something that the audience is already partially familiar with. The key idea is that you wish to engage your audience and convince them that what you are proposing is worth pursuing. In film-making, it’s used to convey an idea to people who need to agree to support it from a financial or authority perspective.

One of the most successful pitches in Hollywood history is (reputedly) the four word pitch used to convince a studio to fund the movie “Twins”. The pitch was “Schwarzenegger. De Vito. Twins.”

You are not trying to sell anything but you are trying to familiarise a group of people with your project idea and communicate enough information that the group can give you useful feedback to improve your project. You need to think carefully about how you will do this and I strongly suggest that you rehearse before presenting. Trust me when I say that very few people are any good at presentation without rehearsal and I will generally be able to tell the amount of effort that you’ve expended. An indifferent presentation says that you don’t care – and then you have to ask why anyone else would be that motivated to help you.

If you like the way I lecture, then you should know that I still rehearse and practice regularly, despite having been teaching for over 20 years.

How will it work?

You will have 10 minutes to present your project outline. During this time you will:

- Identify, in one short and concise sentence, what your poster is about.

- Clearly state the purpose.

- Identify your data source.

- Answer all of the key questions raised in the tutorial.

- Identify your starting strategy, based on the tools given in the tutorial, with a rough outline of a timeline.

- Outline your analysis methodology.

- Summarise the benefits of this selection of data and presentation – why is it important/useful?

- Show a rough prototype layout on an A3 format.

We will then take up to 10 minutes to provide you with constructive feedback regarding any of these aspects. Participants will be assessed both on the pitch that they present and the quality of their feedback and critique. Critique guides will be available for this session.

How do I present it?

This is up to you but I would suggest that you summarise the first seven points as a handout, and provide a copy of your A3 sketch, for reference during critique. You may also use presentations (PowerPoint, Keynote or PDF) if you wish, or the whiteboard. As a guideline, I would suggest no more than four slides, not including title, or your poster sketch. You may use paper and just sketch on that – the idea and your ability to communicate it are paramount at this stage, not the artfulness of the rough sketch.

Important Notes

Some people haven’t been getting all of their work ready on time and, up until now, this has had no impact on your marks or your ability to continue working with the group. If you don’t have your project ready, then I cannot give you any marks for your project and you miss out on the opportunity for group critique and response – this will significantly reduce your maximum possible mark for this project.

I am interested in you presenting something that you find interesting or that you feel will benefit from working with – or that you think is important. The entire point of this course is to give you the chance to do something that is genuinely interesting and to challenge yourself. Please think carefully about your data and your approach and make sure that you give yourself the opportunity to make something that you’d be happy to show other people, as a reflection of yourself, your work and what you are capable of.

END OF THE PITCH DESCRIPTION

We then had a session where we discussed ideas, looked at sources and started to think about how we could get some ideas to build a pitch on. I used small group formation and a bit of role switching and, completely unsurprisingly to the rest of you social constructivists, not only did we gain benefit from the group work but it started to head towards a self-sustaining activity. We went from “I’m not really sure what to do” to something very close to “flow” for the majority of the class. To me it was obvious that the major benefit was that the ice had been broken and, through careful identification of what to happen with the ideas and a deliberate use of Snow’s Cholera diagram as an example of how powerful a good (but fundamentally) simple visualisation could be, the group was much better primed to work on the activity.

The acid test will be next week but, right now, I’m a lot more confident that I will get a good set of first pitches. Given how much I was holding my breath, without realising it, that’s quite a good thing!

Wading In: No Time For Paddling

Posted: July 31, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, feedback, Generation Why, grand challenge, grand challenges, higher education, in the student's head, principles of design, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, universal principles of design, work/life balance 1 CommentI’m up to my neck in books on visualisation and data analysis at the moment. So up to my neck that this post is going to be pretty short – and you know how much I love to talk! I’ve spent most of the evening preparing for tomorrow’s visualising data tutorial for Grand Challenges and one of the things I was looking for was bad visualisations. I took a lot away from Mark’s worked examples posts, and I look forward to seeing the presentation, but visualisation is a particularly rich area for worked ‘bad’ examples. With code, it has to work to a degree or manifest its failure in interesting ways. A graphic can be completely finished and still fail to convey the right information.

(I’ve even thrown in some graphics that I did myself and wasn’t happy with – I’m looking forward to the feedback on those!) (Ssh, don’t tell the students.)

I had the good fortune to be given a copy of Visual Strategies (Frankel and DePace) which was designed by one of the modern heroes of design – the amazing Stefan Sagmeister. This is, without too much hyperbole, pretty much the same as being given a book on painting where Schiele had provided the layout and examples. (I’m a very big fan of Egon Schiele and Hundertwasser for that matter. I may have spent a little too much time in Austria.) The thing I like about this book is that it brings a lot of important talking and thinking points together: which questions should you ask when thinking about your graphic, how do you start, what do you do next, when do you refine, when do you stop?

Thank you, again, Metropolis Bookstore on Swanston Street in Melbourne! You had no real reason to give a stranger a book for free, except that you thought it would be useful for my students. It was, it is, and I thank you again for your generosity.

I really enjoy getting into a new area and I think that the students are enjoying it too, as the entire course is a new area for them. We had an excellent discussion of the four chapters of reading (the NSF CyberInfrastructure report on Grand Challenges), where some of it was a critique of the report itself – don’t write a report saying “community engagement and visualisation are crucial” and (a) make it hard to read, even for people inside the community or (b) make it visually difficult to read.

On the slightly less enthusiastic front, we get to the crux of the course this week – the project selection – and I’m already seeing some hesitancy. Remember that these are all very good students but some of them are not comfortable picking an area to do their analysis in. There could be any number of reasons so, one on one, I’m going to ask them why. If any of them say “Well, I could if I wanted to but…” then I will expect them to go and do it. There’s a lot of scope for feedback in the course so an early decision that doesn’t quite work out is not a death sentence, although I think that waiting for permission to leap is going to reduce the amount of ownership and enjoyment that the student feels when the work is done.

I have no time for paddling in the shallows, personally, and I wade on in. I realise, however, that this is a very challenging stance for many people, especially students, so while I would prefer people to jump in, I recognise my job as life guard in this area and I am happy to help people out.

However, these students are the Distinction/High Distinction crowd, the ones who got 95-100 on leaving secondary school and, as we thought might occur, some of them are at least slightly conditioned to seek my approval, a blessing for their project choice before they have expended any effort. Time to talk to people and work with them to help them move on to a more confident and committed stance – where that confidence is well-placed and the commitment is based on solid fact and thoughtful reasoning!

The 1-Year Degree – what’s your reaction?

Posted: July 30, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: constructive student pedagogy, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, workload 2 CommentsI’m going to pose a question and I’d be interested in your reaction.

“Is there a structure and delivery mechanism that could produce a competent professional graduate from a degree course such as engineering or computer science, which takes place over a maximum of 12 months including all assessment, without sacrificing quality or content?”

What was your reaction? More importantly, what is the reasoning behind your reaction?

For what it’s worth my answer is “Not with our current structures but, apart from that, maybe.” which is why one of my side projects is an attempt to place an entire degree’s worth of work into a 12-month span as a practice exercise for discussing the second and third year curriculum review that we’re holding later on this year.

Our ‘standard’ estimate for any normal degree program is that a student is expected to have a per-semester load of four courses (at 3 units a course, long story) and each of these courses will require 156 hours from start to finish. (This is based on 10 hours per week, including contact and non-contact, and roughly 36 hours for revision towards examination or the completion of other projects.) Based on this estimate, and setting up an upper barrier of 40 hours/week, for all of the good research-based reasons that I’ve discussed previously, there is no way that I can just pick up the existing courses and drop them into a year. A three-year program has six semesters, with four courses per semester, which gives an hour burden of 24*156 = 3,744. At 40 hours per week, we’d need 93.6 weeks (let’s call that 94), or 1.8 years.

But, hang on, we already have courses that are 6-unit and span two semesters – in fact, we have enormous projects for degree programs like Honours that are worth the equivalent of four courses. Interestingly, rather than having an exam every semester, these have a set of summative and formative assignments embedded to allow the provision of feedback and the demonstration of knowledge and skill acquisition – does this remove the need to have 36 hours for exam study for each semester if we build the assignments correctly?

Let’s assume that it does. Now we have a terminal set of examinations at the end of each year, instead of every semester. Now I have 12 courses at 120 hours each and 12 at 156 hours each. Now we’re down to 3,312 – which is only 1.6 years. Dang. Still not there. But it’s ok, I can see all of you who have just asked “Well, why are you so keen on using examinations if you’re happy with summative assignments testing concepts as you go and then building in the expectation of this knowledge in later modules?” Let’s drop the exam requirement even further to a final set of professional level assessment criteria, carried out at the end of the degree to test high-level concepts and advanced skills. Now, of the 24 courses that a student sits, almost all assessment work has moved into continuous assessment mode, rich in feedback, with summative checkpoints and a final set of examinations as part of the four capstone courses at the end. This gives us 3,024 hours – about 1.45 years.

But this is also ignoring that the first week of many of these courses is required revision after some 6-18 weeks of inactivity as the students go away to summer break or home for various holidays. Let’s assume even further that, with the exception of the first four courses that they do, that we build this continuously so that skills and knowledge are reinforced as micro slides, scattered throughout the work, supported with recordings, podcasts, notes, guides and quick revision exercises in the assessment framework. Now I can slice maybe 5 hours off 20 of the courses (the last 20) – cutting me down by another 100 hours and that’s half a month saved, down to 1.4 years.

Of course, I’m ignoring a lot of issues here. I’m ignoring the time it takes someone to digest information but, having raised that, can you tell me exactly how long it takes a student to learn a new concept? This is a trick question as the answer generally depends upon the question “how are you teaching them?” We know that lectures are one of the worst ways to transfer information, with A/V displays, lectures and listening all having a retention rate less than 40%. If you’re not retaining, your chances of learning something are extremely low. At the same time, somewhere between 30-50% of the time that we’re allocating to those courses we already teach are spent in traditional lectures – at time of writing. We can improve retention (of both knowledge and students) when we use group work (50% and higher for knowledge) or get the students to practice (75%) or, even better, instruct someone else (up to 90%). If we can restructure the ’empty’ or ‘low transfer’ times into other activities that foster collaboration or constructive student pedagogy with a role transfer that allows students to instruct each other, then we can potentially greatly improve our usage of time.

If we use this notion and slice, say, 20 hours from each course because we can get rid of that many contact hours that we were wasting and get the same, if not better, results, we’re down to 2,444 hours, about 1.18 years. And I haven’t even started looking at the notion of concept alignment, where similar concepts are taught across two different concepts and could be put in one place, taught once, consistently and then built upon for the rest of the course. Suddenly, with the same concepts and a potentially improved educational design – we’re looking the 1-year degree in the face.

Now, there will be people who will say “Well, how does the student mature in this time? That’s only one year!” to which my response is “Well, how are you training them for maturity? Where are the developing exercises? The formative assessment based on careful scaffolding in societal development and intellectual advancement?” If the appeal of the three-year degree is that people will be 19-20 when they graduate, and this is seen as a good thing, then we solve this problem for the 1-year degree by waiting two years before they start!

Having said all of this, and believing that a high quality 1-year degree is possible, let me conclude by saying that I think that it is a terrible idea! University is more than a sequence of assessments and examinations, it is a culture, a place for intellectual exploration and the formation of bonds with like-minded friends. It is not a cram school to turn out a slightly shell-shocked engineer who has worked solidly, and without respite, for 52 weeks. However, my aim was never actually to run a course in a year, it was to see how I could restructure a course to be able to more easily modularise it, to break me out of the mental tyranny of a three- or four-year mandate and to focus on learning outcomes, educational design and sound pedagogy. The reason that I am working on this is so that I can produce a sound course structure with which students can engage, regardless of whether they are full-time or not, clearly outlining dependency and requirements. Yes, if we break this up into part-time, we need to add revision modules back in – but if we teach it intensively (or on-line) then those aren’t required. This is a way to give students choice and the freedom to come in at any age, with whatever time they have, but without sacrificing the quality of the underlying program. This is a bootstrap program for a developing nation, a quick entry point for people who had to go to work – this is making up for decades of declining enrolments in key areas.

This is going on a war footing against the forces of ignorance.

There are many successful “Open” universities that use similar approaches but I wanted to go through the exercise myself, to allow me the greatest level of intellectual freedom while looking at our curriculum review. Now, I feel that I can focus on Knowledge Areas for my specifics and on the program as a whole, freed of the binding assumption that there is an inevitable three-year grind ahead for any student. Perhaps one of the greatest benefits for me is the thought that, for students who can come to us for three years, I can put much, much more into the course if they have the time – and these things, of interest, regarding beauty, of intellectual pursuits, can replace some of the things that we’ve lost over the years in the last two decades of change in University.