Reflection on Work Load: I may have been too convincing

Posted: August 22, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, education, educational problem, higher education, teaching, time banking, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentI’m a bit of a hypocrite when it comes to taking my own advice on exercise. “Start easy,” I say, as I come back from injury with a fast 10 mile run. “Don’t over do it!” I admonish as I try to lift my own body weight in a gym. I have two knee surgeries, multiple calf strains and a torn plantar fascia to bear witness to this. For this, and many other reasons, I have a personal training for the gym stuff who I see once a week and a running partner who (facetiously) threatens to slap me if I run too hard or too far. I’m more scared of her than I am my personal trainer but don’t tell her that.

To fit everything in, I train in the gym at 6am on Wednesdays and, while this gives me a long day it allows me to get some good core and upper body work in to balance my legs and overall fitness – strength is useful in many ways as a day-to-day thing but balance, the other effect of good core strength, is incredibly useful and makes me a much better runner. I also take the opportunity to talk to someone who doesn’t work with me, isn’t related to me and knows what I do, but not in much detail. It’s very relaxing to talk to someone like that, especially when you have things on your mind.

Time Banking has been on my mind, as has my own time management, so I’ve talked a lot about making my life more effective, working less and working better, all those good things. So imagine my surprise when my trainer wrote to me asking if we could move sessions a little, if possible, as he’d been listening to what I’d been saying and realised that he’d been working reactively by not allowing himself enough time to plan and structure his day, especially as he’s now managing the gym I train at.

I’ve been thinking about changing away from the Wednesday 6 slot and this means that this is great timing for me. I’d like to keep training with him but I could train with someone else who doesn’t have his burdens or schedule quite easily and still have a really good experience – I’ve trained with other people before there, it’s a good gym. But what I really like is the thought process – contemplative and transformative.

Now, either this is the greatest con job that I’ve been privy to or I may have actually helped someone else to see a new way of thinking about their own life. Either way, there appears to be some knowledge transfer going on.

One person at a time. It’s slow but I can work with that. 🙂

Short and Sweet

Posted: August 21, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, community, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, workload 1 CommentWell, it’s official. I’ve started to compromise my ability to work through insufficient rest. Despite reducing my additional work load, chewing through my backlog is keeping me working far too much and, as you can tell from the number and nature of the typos in these posts, it’s affecting me. I am currently reorganising tasks to see what I can continue to fit in without compromising quality, which means this week a lot of e-mail is being sent to sort out my priorities.

This weekend, I’m sitting down to brainstorm the rest of 2012 and work out what has to happen when – nothing is going to sneak up on me (again) this year.

In very good news, we have 18 students coming back for the pilot activity of “Our students, their words” where we ask students who love ICT an important question – “what do you like and why do you think someone else might like it?” We’re brainstorming with the students for all of Friday morning and passing their thoughts (as research) to a graphic designer to get some posters made. This is stage 1. Stage 2, the national campaign, is also moving – slowly but surely. This is why I really need to rest: I’m getting to the point where it’s important that I am at my best and brightest. Sleeping in and relaxing is probably the best thing I can do for the future of ICT! 🙂

Rather than be a hypocrite, I’m switching to ultra-short posts until I’m rested up enough to work properly again.

See you tomorrow!

A (measurement) league of our own?

Posted: August 19, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, education, educational problem, higher education, learning, measurement, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches, workload 1 CommentAs I’ve mentioned before, the number of ways that we are being measured is on the rise, whether it’s measures of our research output or ‘quality’, or the impact, benefits, quality or attractiveness of our learning and teaching. The fascination with research quality is not new but, given that we have had a “publish or perish” mentality where people would put out anything and be called ‘research active’, a move to a quality focus (which often entails far more preparation, depth of research and time to publication) from a quantity focus is not a trivial move. Worse, the lens through which we are assessed can often change far faster than we can change those aspects that are assessed.

If you look at some of the rankings of Universities, you’ll see that the overall metrics include things like the number of staff who are Nobel Laureates or have won the Fields Medal. Well, there are less than 52 Fields medallists and only a few hundred Nobel Laureates and, as the website itself distinguishes, a number of those are in the Economics area. This is an inherently scarce resource, however you slice it, and, much like a gallery that prides itself on having an excellent collection of precious art, you are more likely to be able to get more of these slices if you already have some. Thus, this measure of the research presence of your University is a bit of feedback loop.

Similarly the measurement of things like ‘number of papers in the top 20% of publications’. This conveniently ignores some of the benefits of being at better funded institutions, being part of an established community, being invited to lodge papers, and so on. Even where we have anonymous submission and evaluation, you don’t have to be a rocket scientist to spot connections, groups, and, of course, let’s not forget that a well-funded group will have more time, more resources, more postdocs. Basically, funding should lead to better results which leads to better measurement which may lead to better funding.

In terms of high prestige personnel, and their importance, or a history of quality publication, neither of these metrics can be changed overnight. Certainly a campaign to attract prestigious staff might be fruitful in the short term but, and let us be very frank here, if you can buy these staff with a combination of desirable locale issues and money, then it is a matter of bidding as to which University they go to next. But trying to increase your “number of high end publications in the last 5 years” is going to take 5 years to improve and this is kind of long-term thinking that we, as humans, appear to be very bad at.

Speaking of thinking in the long term, a number of the measures that would be most useful to us are not collected or used for assessment because they are over large timescales and, as I’ll discuss, may force us to realise that some things are intrinsically unmeasurable. Learning and teaching quality and impact is intrinsically hard to measure, mainly because we rarely seem take the time to judge the impact of tertiary institutions over an appropriate timescale. Given the transition issues in going from high school to University, measuring drop-out and retention rates in a student’s first semester leaves us wondering who is at fault. Are the schools not quite doing the job? Is it the University staff? The courses? The discipline identity? The student? Yes, we can measure retention and do a good job, with the right assessment, of maturing depth and type of knowledge but what about the core question?

How can we measure the real impact of undertaking studies in our field at our University?

After all, this is what these metrics are all about – determining the impact of a given set of academics at a given Uni so you can put them into a league table, hand out funding in some weighted scheme or tell students which Uni they should be going to. Realistically, we should come back in twenty years and find out how much was used, where their studies took them, whether they think it was valuable. How did our student use the tools we gave them to change the world? Of course, how do we then present a control to determine that it was us who caused that change. Oh, obviously a professional linkage is something we can think of as correlated – but not every engineer is Brunel and, most certainly, you don’t have to have gone to University to change the world.

This is most definitely not to say that shorter term measures of l&t quality aren’t important but we have to be very careful what we’re measuring and the reason that we’re measuring – and the purpose to which we put it. Measuring depth of knowledge, ability to apply that knowledge and professionally practice in a discipline? That’s worth measuring if we do it in a way that encourages constructive improvement rather than punishment or negative feedback that doesn’t show the way forward.

I don’t mind being measured, as long as it’s useful, but I’m getting a little tired of being ranked by mechanisms that I can’t change unless I go back in time and publish 10 more papers over the last 5 years or I manage to heal an entire educational system just so my metrics improve for reducing first-year drop out. (Hey, just so you know, I am working on increasing number of ICT students on a national level – you do have to think on the large scale occasionally.)

Apart from anything else, I wouldn’t rank my own students this way – it’s intrinsically arbitrary and unfair. Food for thought.

You Are Reading This on My Saturday

Posted: August 18, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, collaboration, community, education, educational problem, ethics, higher education, in the student's head, learning, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, workload 1 CommentAh, time zones. Because of these divisions of time, what publishes at 4:00am Saturday morning, Australian Central Standard Time, will be read by some of you on Friday. It is, however, important to realise that I am writing this on Friday evening, around 8:30pm, so that will help you to determine the context. You may not need it because my question is simple:

“What are you doing this weekend?”

If your answer is anything along the lines of spending time with the kids, sports, reading, writing the world’s worst screen play, going to the theatre, checking out the new cafe down on market – then bravo! If your answer is anything along the lines of “working” then, while I don’t doubt that you feel the genuine need to work, I do have to wonder about any weekend that features as much, if not more, work than a weekday.

I’m very guilty in this particular exchange. My wife has returned home after only two weeks away and I’ve already started to slip back into bad habits – not just doing work on weekends because I needed to, but assigning work to weekends as if they were weekdays.

See the difference there? It’s the difference between the reserve chute and the main chute, the emergency petrol in the jerry can to the fuel tank – it’s the difference between a temporary overload and workaholism.

I understand that many of you are under a great deal of pressure to perform, to put marks on a well-define chalkboard, to bring in money, to publish, to teach well, to do all of that and, right now, there aren’t enough hours in the week let alone the day. However, how you frame this mentally makes a big difference to how you continue to act… and I speak from bitter, bitter experience here.

Yesterday, I talked about things that I hadn’t achieved. Yet, today, I talk about taking the weekend off. No work. Minimal e-mail. Fun as a priority. Why?

Because the evidence clearly indicates that the solution to my problem lies in getting rest and sleep, not by reducing my ability to work effectively by working longer hours, less effectively. If I am to get the whole concept of student time management right, then it should work for me as well – as I’ve said numerous times. My dog food. Here’s a spoon. Eat it up.

Are you working so hard that you can’t focus? Is it actually taking you twice as long to get things done?

Then rest. Sleep in. Take a day off. By simple arithmetic, skipping a day to get back to higher efficacy is a good investment. Stop treating the weekends as conveniently quiet days where nobody bothers you – because everyone else has taken the day off.

That’s what I noticed when I started working weekends. The reason it was quieter is that, most of the time, no-one else was there. Ok, maybe they didn’t ‘achieve’ as much as I did – but how did they look? Were they grey, or jaundiced, tired and listless, possibly even angry and frustrated on Monday morning? Or were they bright and happy, full of weekend chatter? Did you, pale and wan, resent them for it?

Look, we all have to work weekends now and then and pull the occasional all-nighter, but making it a part of your schedule and, worse, cancelling your life in order to work because you tell yourself that this is a permanent thing? That’s not right. If it was right, your office would be full on weekends and at 10pm. (p.s. if that’s your company, and you’re working 80 hours a week, you’re terribly inefficient. Pass it on.)

Now, I’m going off to sleep. I will post some more over this weekend but most of it is scheduled. Let’s see if I can practice what I preach.

Talk to the duck!

Posted: August 17, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, grand challenge, higher education, principles of design, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, time banking, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentI’ve had a funny day. Some confirmed acceptances for journals and an e-mail from a colleague regarding a collaboration that has stalled. When I set out to readjust my schedule to meet a sustainable pattern, I had a careful look at everything I needed to do but I overlooked one important thing: it’s easier to give the illusion of progress than it is to do certain things. For example, I can send you a ‘working on it’ e-mail every week or so and that takes me about a minute. Actually doing something could take 4-8 hours and that’s a very large amount of time!

So, today was a hard lesson because I’ve managed to keep almost all of the balls in the air, juggling furiously, as I trim down my load but this one hurts. Right now, someone probably thinks that I don’t care about their project – which isn’t true but it fell into the tough category of important things that needs a lot of work to get to the next stage. I’ve sent an apologetic and embarrassed e-mail to try and get this going again – with a high prioritisation of the actual work – but it’s probably too late.

The project in question went to a strange place – I was so concerned about letting the colleague down that I froze up every time I tried to do the work. Weird but true and, ultimately, harmful. But, ultimately, I didn’t do what I said I’d do and I’m not happy.

So how can I turn this difficult and unpleasant situation into something that I can learn from? Something that my students can benefit from?

Well, I can remember that my students, even though they come in at the start of the semester, often come in with overheads and burdens. Even if it’s not explicit course load, it’s things like their jobs, their family commitments, their financial burdens and their relationships. Sometimes it’s our fault because we don’t correctly and clearly specify prerequisites, assumed knowledge and other expectations – which imposes a learning burden on the student to go off and develop their own knowledge on their own time.

Whatever it is, this adds a new dimension to any discussion of time management from a student perspective: the clear identification of everything that has to be dealt with as well as their coursework. I’ve often noticed that, when you get students talking about things, that halfway through the conversation it’s quite likely that their eyes will light up as they realise their own problem while explaining things to other people.

There’s a practice in software engineering that is often referred to as “rubber ducking”. You put a rubber duck on a shelf and, when people are stuck on a problem, they go and talk to the duck and explain their problem. It’s amazing how often that this works – but it has to be encouraged and supported to work. There must be no shame in talking to the duck! (Bet you never thought that I’d say that!)

I’m still unhappy about the developments of today but, for the purposes of self-regulation and the development of mature time management, I’ve now identified a new phase of goal setting that makes sense in relation to students. The first step is to work out what you have to do before you do anything else, and this will help you to work out when you need to move your timelines backwards and forwards to accommodate your life.

This may actually be one of the best reasons for trying to manage your time better – because talking about what you have to do before you do any other assignments might just make you realise that you are going to struggle without some serious focus on your time.

Or, of course, it may not. But we can try. We can try with personal discussions, group discussions, collaborative goal setting – students sitting around saying “Oh yeah, I have that problem too! It’s going to take me two weeks to deal with that.” Maybe no-one will say anything.

We can but try! (And, if all else fails, I can give everyone a duck to talk to. 🙂 )

Putting it all together – discussing curriculum with students

Posted: August 15, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, collaboration, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, popeye, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, wimpy, workload Leave a commentOne of the nice things about my new grand challenges course is that the lecture slots are a pre-reading based discussion of the grand challenges in my discipline (Computer Science), based on the National Science Foundation’s Taskforce report. Talking through this with students allows us to identify the strengths of the document and, perhaps more interestingly, some of its shortfalls. For example, there is much discussion on inter-disciplinary and international collaboration as being vital, followed by statements along the lines of “We must regain the ascendancy in the discipline that we invented!” because the NSF is, first and foremost, a US-funded organisation. There’s talk about providing the funds for sustainability and then identifying the NSF as the organisation giving the money, and hence calling the shots.

The areas of challenge are clearly laid out, as are the often conflicting issues surrounding the administration of these kinds of initiative. Too often, we see people talking about some amazing international initiative – only to see it fail because nobody wants to go first, or no country/government wants to put money up that other people can draw on until everyone does it at the same time.

In essence, this is a timing and trust problem. If we may quote Wimpy from the Popeye cartoons:

The NSF document lays bare the problem we always have: those who have the hamburgers are happy to talk about sharing the meal but there are bills to be paid. The person who owns the hamburger stand is going to have words with you if you give everything away with nothing to show in return except a promise of payment on Tuesday.

Having covered what the NSF considered important in terms of preparing us for the heavily computerised and computational future, my students finished with a discussion of educational issues and virtual organisations. The educational issues were extremely interesting because, having looked at the NSF Taskforce report, we then looked at the ACM/IEEE 2013 Computer Science Strawman curriculum to see how many areas overlapped with the task force report. Then we looked at the current curriculum of our school, which is undergoing review at the moment but was last updated for the 2008 ACM/IEEE Curriculum.

What was pleasing was, rom the range of students, how many of the areas were being addressed throughout our course and how much overlap there was between the highlighted areas of the NSF Report and the Strawman. However, one of the key issues from the task force report was the notion of greater depth and breadth – an incredible challenge in the time-constrained curriculum implementations of the 21st century. Adding a new Knowledge Area (KA) to the Strawman of ‘Platform Dependant Computing’ reflects the rise of the embedded and mobile device yet, as the Strawman authors immediately admit, we start to make it harder and harder to fit everything into one course. Combine this with the NSF requirement for greater breadth, including scientific and mathematical aspects that have traditionally been outside of Computing, and their parallel requirement for the development of depth… and it’s not easy.

The lecture slot where we discussed this had no specific outcomes associated with it – it was a place to discuss the issues arising but also to explain to the students why their curriculum looks the way that it does. Yes, we’d love to bring in Aspect X but where does it fit? My GC students were looking at the Ethics aspects of the Strawman and wondered if we could fit Ethics into its own 3-unit course. (I suspect that’s at least partially my influence although I certainly didn’t suggest anything along these lines.) “That’s fine,” I said, “But what do we lose?”

In my discussions with these students, they’ve identified one of the core reasons that we changed teaching languages, but I’ve also been able to talk to them about how we think as we construct courses – they’ve also started to see the many drivers that we consider, which I believe helps them in working out how to give feedback that is the most useful form for us to turn their needs and wants into improvements or developments in the course. I don’t expect the students to understand the details and practice of pedagogy but, unless I given them a good framework, it’s going to be hard for them to communicate with me in a way that leads most directly to an improved result for both of us.

I’ve really enjoyed this process of discussion and it’s been highly rewarding, again I hope for both sides of the group, to be able to discuss things without the usual level of reactive and (often) selfish thinking that characterises these exchanges. I hope this means that we’re on the right track for this course and this program.

The Key Difference (or so it appears): Do You Love Teaching?

Posted: August 12, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, blogging, collaboration, community, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, higher education, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, workload 3 CommentsI wander around fair bit for work. (I make it sound more impressive than that but the truth is that I end up in lots of different places to work on my many projects and sometimes the movement, although purposeful, is more Brownian than not – due to life.) I’ve had a chance to talk to a lot of people who teach – some of whom are putting vast amounts of effort into it and some of whom aren’t.

The key difference, unsurprisingly, is generally the passion behind it. We see this in our students. They will spend days working on a Minecraft construction to simulate an Arithmetic and Logic Unit, but won’t always put in the two hours to write 20 lines of C++ code. They will write 20,000 words on their blog but can’t give you a 1,000 word summary.

We put effort into the things that we are interested in. Sure, if we’re really responsible and have self-regulation nailed, then we can do things that we’re not interested in, or actively dislike, but it’s never really going to have the same level of effort or commitment.

Passion (or the love of something) is crucial. Some days I have so much to say on the blog that I end up with 4-5 days stocked up in the queue. Some days I struggle to come up with the daily post or, as yesterday, I just run out of time to hit the 4am post cycle because I am doing other things that I am passionate about. Today, of course, the actual deadline timer is running and it seems to have made me think – now I’m passionate and now you’ll get something worth reading. If I’d stayed up until after my guests had left last night, written just anything to meet the deadline? It wouldn’t be anywhere near my best work.

Passion is crucial.

Which brings me to teaching. I know a lot of academics – some who are research/teaching/admin, some research only, some teaching/admin and… well, you get the picture. The majority are the ‘3-in-1’ academics and, in many regards, looking at their student evaluations and performance metrics will not tell you anything about them as a teacher that you can’t learn by sitting down with them and talking about their teaching. It is hard to shut me up about my courses and my students, the things I’m trying, the things I’m thinking of adopting, the other areas I’m looking at, the impact of what other Unis and people are doing, the impact of reports. I am a (junior) scholar in the discipline of learning and teaching and I really, really love teaching. For me, putting effort into it is inevitable, to a great extent.

Then I talk to colleagues who really just want to do their research and be left alone. Everything else is a drag on their research. Administration will get the minimum effort, if it’s done. Teaching is something that you have to do and, if the students don’t get it, then it’s their fault. What is so weird about this is that these people are, in the vast majority, excellent scholars in their own discipline. They research and read heavily, they are aware of what every other researcher is doing in this area, they know if their work has a chance for publication or grants. Having these skills, they then divide the world into ‘places where I have to scholarly’ and ‘places where I can phone it in’. (Not all researchers are like this, I’m talking about the ones who consider anything other than research beneath them.)

What a shame! What a terrible missed opportunity for both these people who should be more aware of the issues of learning and teaching, and for the students who could be learning so much more from them? But when you actually talk to these academics, some of them just don’t liked teaching, they don’t see the point of putting effort into it or (in some cases) they just don’t know what to do and how to improve so they hunker down and try to let it all slide around them.

Part of this is the selective memory that we have of ourselves as students. I’m lucky – I was terrible. I was fortunate enough to be aware and mature enough as I reconstructed myself as a good student to see the transformative process in action. A lot of my peers are happy to apply rules to students that they wouldn’t (or don’t ) apply to themselves now or in the past, such as:

“I’m an academic who doesn’t like teaching, despite being told that it’s part of my job, so I’ll do the minimum required – or less on some occasions. You, however, are a student who doesn’t like the sub-standard learning experiences that my indifference brings you but I’m telling you to do it, so just do it or I’ll fail you.”

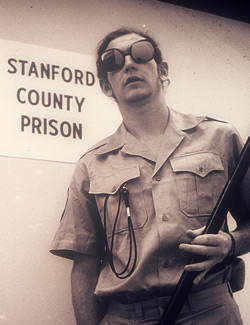

This isn’t just asymmetrical, this is bordering on the Stanford Prison Experiment, an arbitrary assignation of roles that leads to destructive power-derived behaviour. But, if course, if you don’t enjoy doing something then there are going to be issues.

Have we actually ever asked people these key questions as a general investigation? “Do you like teaching?” “What do you enjoy about teaching?” “What can we do to make you enjoy teaching more?” Would this muddy the water or clear the air? Would this earth our non-teaching teachers and fire them up?

Even where people run vanity courses (very small scale, research-focused courses design to cherry pick the good students) they are still often disappointed because, even where you can muster the passion to teach, if you don’t really understand how to teach or what you need to do to build a good learning experience, then you end up with these ‘good’ students in this ‘enjoyable’ course failing, complaining, dropping out and, in more analogous terms, kicking your puppy. You will now like teaching even less!

It’s blindingly obvious that some people don’t like teaching but, much as we wouldn’t stand out the front of a class and yell “PASS, IDIOTS!”, I’m looking for other good examples where we start to ask people why they don’t want to do it, what they’re worried about, why they don’t respect it and how we can get them more involved in the L&T community.

Let’s face it, when you love teaching, the worst day with the students is still a pretty good day. It would be nice to share this joy further.

Teaching Ethics in a Difficult World: Free Range and Battery Games

Posted: August 9, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, community, education, educational problem, ethics, free range games, games, higher education, in the student's head, principles of design, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, workload 2 Comments(Note, this is not a post about the existing game company, Free Range Games, although their stuff looks cool!)

I enjoy treating ethics or, to be more precise, getting the students to realise the ethical framework that they all live within. I’ve blogged before about this and how easy it is to find examples of unethical behaviour but, as we hear more stories about certain ‘game-related’ industries and the way that they teach testers, it becomes more and more apparent that we are reaching a point where the ethical burden of a piece of software may end up becoming something that we have to consider.

We’re already aware of the use of child labour in some products and people can make a decision not to shop at certain stores or buy certain products – but this requires awareness and tying the act to the brand.

In the areas I live in, it’s very hard to find a non-free range chicken, even in a chicken take-away shop (for various definitions of ‘free range’ but we pretty much do mean ‘neither battery nor force fed’) and eggs are clearly labelled. Does this matter to you? If so, you can make an informed decision. Doesn’t matter to you? Buy the cheapest or the tastiest or whichever other metric you’re using.

But what about games? You don’t have to look far (ea_spouse and the many other accounts available) to see that the Quality Assurance roles, vital to good games, are seeing a resurgence in the type of labour management that is rapidly approaching the Upton Sinclair Asymptote. Sinclair wrote a famous turn-of-the 20th Century novelisation of the conditions in the meat packing industry, “The Jungle”, that, apart from a rather dour appeal to socialism at the end, is an amazing read. It changed conditions and workers’ rights because it made these invisible people visible. Once again, as well apparently fall in love with the ‘wealth creators’ (an Australian term that is rapidly become synonymous with ‘robber baron’) all over again, we are approaching this despite knowing what the conditions are.

What I mean by this is that it is well known that large numbers of staff in the QA area in games tolerate terrible conditions – no job security, poor working conditions, malicious and incompetent management – and for what? To bring you a game. It’s not as if they are fighting to maintain democracy (or attack democracy, depending on what you consider to be more important) or staying up for days on end trying to bring the zombie infection under control. No, the people who are being forced into sweatboxes, occasionally made to work until they wet themselves, who are unceremoniously fired at ‘celebration’ events, are working to make sure that the people who wrote your game didn’t leave any unexplained holes in the map. Or that, when you hit a troll with an axe, it inflicts damage rather than spontaneously causing the NyanCat video to play on your phone.

This discussion of ethics completely ignores the ethics of computer games that demean or objectify women, glorify violence or any of the ongoing issues. Search for ethics of video games and it is violence and sexism that dominates the results. It’s only when you start searching for “employee abuse video game” that you start to get hits. Here are some quotes from one of them.

It seems as though the developers of L. A. Noire might have been under more pressure themselves than any of the interrogated criminals in their highly praised crime drama. Reports have surfaced about employees being forced to work excruciating hours, in some cases reaching 120 hour weeks and 22 hour days. In addition, a list has been generated of some 130 members of the Australian-based Team Bondi, the creators of L. A. Noire, whose names have been omitted from the game’s own credits.

…

On the subject of the unprecedented scope of the project for Australian developers, McNamara replied, “The expectation is slightly weird here, that you can do this stuff without killing yourself; well, you can’t, whether it’s in London or New York or wherever; you’re competing against the best people in the world at what they do, and you just have to be prepared to do what you have to do to compete against those people. The expectation is slightly different.”

The saddest thing, to me, is that everyone knows this. The same people who complain on my FB feed back how overworked they are and how little they see their family then go out and buy games that have been produced in electronic sweatshops. You didn’t buy L. A. Noire? Rockstar San Diego are on the “overworking staff” list for “Red Dead Redemption” and the “not crediting everyone” for “Manhunt 2”. (That last one might not be so bad!)

Everyone talks about the crunch as if it’s unavoidable. Well, yes , it is, if you intend to work people to the crunch. We’ve seen similar argument for feedlot meat production, battery animals and, let’s not forget, that there have always been “excellent” reasons for slavery in economic and social terms.

This is one of the hardest things to talk about to my students because they’re not dumb. They read, often more widely than I do in these areas. They know that for all my discussions of time management and ethics, if they get a certain kind of job they will work 7 days a week, 10-14 hours a day, in terrible conditions and maybe, just maybe, if they sell their soul enough they can get a full-time job, rather than being laid off indiscriminately. They know that the message coming down from these companies is “maximum profit, minimum spend” and, of course, most of these game companies aren’t profitable so that’s less about being mercenary and more about survival.

But, given that these products are not exactly… essential (forgive me, Deus Ex!), one has to wonder whether terms like ‘survival’ have any place in this discussion. Is it worth nearly killing people, destroying their social lives and so one, to bring a game to market? People often say “Well, they have a choice” and, in some ways, I suppose they do – but in an economic market where any job is better than job, and people can make decisions at 15 that lead to outcomes they didn’t expect at 25, this seems both ungenerous and thoughtless.

Perhaps we need the equivalent of a ‘Free Range/Organic’ movement for games: All programmers and QA people were officially certified to have had at least 8 hours sleep a night, with a minimum break of 50 hours every 6 days and were kept at a maximum density of 2 programmers per 15 square metres, in a temperature and humidity controlled environment that meets recognised comfort standards.

(Yeah, I didn’t include management. I think they’re probably mostly looking after themselves on that one. 🙂 )

Then you can choose. If it matters to you, buy 21st century Labour Force Games – Ethically and sustainably produced. If it doesn’t matter, ignore it and game on.

Two Speeds: Nothing and Ultra High Speed

Posted: August 8, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, higher education, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, workload 1 CommentShort post today. I’m reminded that, even with the best view of what you have to do, any time that you have in your calendar to do things can easily disappear when the unexpected strikes. I had this week planned as a reasonably paced week, with some paper writing. Now I’m looking at a week where I have one unscheduled 30 minute period until Friday evening.

Was this poor planning? No, I had my calendar planned with preparation time and all days were sitting under at my 70% scheduled limit, well under, in fact, because I wanted to allow as much drop-in time as possible for my students. However, now the time has filled up and, yet, all of my deadlines for this week still apply – plus some more on top.

It’s a reminder that stuff happens sometimes and, as we (eventually) start writing the time banking papers, it’s important to remember how easy it is to go from “everything’s cool” to “oh no, my brain is on fire!”. Now I have a lot of experience in handling brain fire but, even so, it’s that nasty little shock that means that there will be no early nights for me until Sunday. This is a surge week, a stretch week, so the usual 45 hour upper limit (the guideline to see if I can get everything done) is on hiatus but will be reset for Monday.

Now this is important because I have, so far, been able to get everything done within the time that I’ve been allocating, I’ve been more relaxed and I’ve been more effective. Today wasn’t the best day in some ways because the wheels had started to fall off and most of my day was spent planning in one part of my head while working with the other.

I see students hit this point a lot and an important part of my job is talking them down from the ledge, in effect. It’s very hard for people who are working o hard, and not getting everything done, to think that working fewer hours will allow them to achieve their goals. So far, I’ve been able to do it, as long as I am open to the occasional burst of week but, at the moment, I’m sitting the limit at 1 week.

We’ll see if that works!