The Complex Roles Of Universities In The Period Of Globalization – Altbach – Part 3

Posted: September 25, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, community, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, Generation Why, higher education, principles of design, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentTo finish this triptych, I’d like to look at Altbach’s assessment of contemporary issues. Private education providers are one of the most obvious recent developments and, with the erosion of the public good motivator, this is no real surprise. It’s less of a surprise when you affix the word “Profit-making” in front of the words ‘education provider’. Given that there is growing demand for education and also given that we are blurring the lines between the institutions, it becomes easy to see why a new market has exploded for people who wish to provide education, or something like it, at a reasonable fee with a possibility of making lots and lots of money. This, however, has an impact on the public sector because it reduces the students who may have come to us for a variety of reasons, especially when the private institutions are targeting the more wealthy in some way. Suddenly, we find ourselves having to justify which kinds of knowledge we are teaching in the public sector because the type of knowledge, and the jobs it leads to, become an issue when you are competing for students inside certain professional areas. Faculties of Arts across the world are very much feeling themselves caught in this pinch. It is hard to imagine many older Universities making such a bald statement such as “There is no need for History or English Scholars”, yet by pumping resources into their professional and technical streams they are saying it through their resource distribution. If something does not provide income or attract the right market, a jaded eye is cast across it and, depending on the wealth and capacity of the institution, this leads to the shutting down of schools or entire faculties.

Why is this such a problem? Because restarting a discipline is much harder once the number of participants drops down too far. Reduce the number of people in a discipline and their shared publications and venues also shrink. Given that publication is vital to perceived success in many ways, this shrinkage will make it harder to publish OR lead to accusations of irrelevance as the overall citation level drops because there are so few people in the area. We are so heavily measured and assessed, as individuals and as universities, that we are beleaguered by league tables and beset by set publication standards. Our management structures, modes of accountability, the way that we have worked and thought for centuries are not a good fit for this new modality. This is not the golden age ramblings that I have previously pointed to as dreaming of better days – in this case, it’s true. Our systems don’t work with the new expectations.

Opening ourselves up to students from anywhere is a noble goal, and one I support wholeheartedly, but it brings great challenge. Can we pursue anything that interests us, relevant or not, and expect to meet the demands of the new century? If we can, I don’t think we can do it with the systems that we have and certainly not while we’re being measured on externally applied metrics of success. Even deciding on whether a student should be admitted or not is now a matter of school ranking, bonus points, place availability, status and, in murkier waters, the two speed entry system of public and privately-funded places in the same institution, where admitting one party may (in the worst case) prevent another from entering. As Altbach notes, our ideas of governance are changing as our scale grows and our complexity increases. Senior Professors used to set our course but now we either need or have taken on trained administrators who do not think as we do, have not had our training and, in many ways, treat us as a standard business with a strange product. We are more accountable than ever, while we wander around being randomly measured and trying to work out what it is that we need to do in order to be measured accurately and then try and perform our tasks of learning, teaching and research. How do we reconcile the community of scholars with the bureaucracies that run our institutions?

Altbach then moves on to discuss developing countries and the special challenges that they face. Many of these countries have broken links to their indigenous cultures, due to colonisation, occupation, war and civil unrest, and, when combined with the colonial trend to keep investment in higher education low, this means that many of these countries are systematically disadvantaged. Their systems are so small that expansion is hard – insufficient training grounds for new educators, delay in building and resource appropriation and the threat of instability combine to make it very hard to kickstart anything. Poverty and lack of local government resources move some of these attempts across to the ‘impossible’ category. As it becomes hard to limit enrolments, overcrowding is the norm and, while you can’t limit enrolment, you can use draconian measures to ensure that anyone who falls behind is ejected, in the hope that freeing up that slot might ease some of the crush on the resources. This is a very unforgiving approach to education: you have one chance, you blew it, goodbye. Given that this is one of the only paths out of poverty in many of these countries, and that it is very easy to fall behind in a poor and resource-starved system, this is a nasty little feedback loop. Where other institutions are built up in response to demand, these newer academies tend not to offer the same level of education and we once again have the problem of a piece of paper that is not as worthy as another: we are providing education in name only and creating yet another two-speed system. Where the job market and the educational bodies don’t keep up with each other you may have that most awful ghetto: the educated unemployed, who have invested time and money into a degree that grants them no advantage at all.

Where we are over-stretched, we tend to only do those things that generate the most benefit and this is also true in the case of these third world Universities. Teaching earns money so teaching dominates. Research is sidelined, international collaboration is sidelined and staff have no time to do anything except teach because they are trying to keep their salary coming. Unsurprisingly, this is not a stage set of excellence and advancement – these universities are falling further and further behind.

Altbach concludes by talking about the pressure that we are all under and that have made the majority of our institutions reactive, limiting our creativity to solving pressing problems in a response to external pressures. Right now, we are running so fast that we do not have time to question why we are even on this treadmill, let alone take any real steps to make serious change that is truly strategic rather than reactive. We have lost our autonomy to a degree, as well as our identity. We are enmeshed in society but in a role that favours the market forces and makes us dance in response to it. Altbach ponders what our role should be and proposes a move towards the broader public interest, moving away from market forces and towards academic autonomy.This is not the selfish “leave me alone” cry of a spoiled child, this is a recognition of the fact that we have many more things to offer than a diploma and a vocation: universities are societies of thinkers and are far more complex and diverse than our current strictures would make us appear. All universities are important, says Altbach, and it is at society’s peril that it ignores the many roles that a University can provide. Looking at us as profit-making, degree factories, or as an elite streaming system, ignores the grand public benefit of an educated society, the value of the public intellectual and the scholarly community. We deserve support, says Altbach, because serve the goals of society and the individual. Let us do our jobs properly.

I found it to be a very interesting article to read and I hope I’ve capture the essence reasonably well. I look forward to discussing it! Thanks again, RV!

Let’s Transform Education! (MOOC Hijinks Hilarity! Jinkies!)

Posted: September 1, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, design, education, educational problem, ethics, grand challenge, higher education, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, universal principles of design, work/life balance, workload 4 CommentsI had one of those discussions yesterday that every one in Higher Education educational research comes to dread: a discussion with someone who basically doesn’t believe the educational research and, within varying degrees of politeness, comes close to ignoring or denigrating everything that you’re trying to do. Yesterday’s high point was the use of the term “Mr Chips” to describe the (from the speaker’s perspective) incredibly low possibility of actually widening our entrance criteria and turning out “quality” graduates – his point was that more students would automatically mean much larger (70%) failure rates. My counter (and original point) is that since there is such a low correlation between school marks and University GPA (roughly 40-45% and it’s very noisy) that successful learning and teaching strategies could deal with an influx of supposedly ‘lower quality’ students, because the quality metric that we’re using (terminal high school grade or equivalent) is not a reliable indicator of performance. My fundamental belief is that good education is transformative. We start with the students that schools give us but good, well-constructed, education can, in the vast majority of cases, successfully educate students and transform them into functioning, self-regulating graduates. We have, as a community, carried out a lot of research that says that this works, provided that we are happy to accept that we (academics) are not by any stretch of the imagination the target demographic or majority experience in our classes, and that, please, let’s look at new teaching methods and approaches that actually work in developing the knowledge and characteristics that we’re after.

The “Mr Chips” thing is a reference to a rather sentimental account of the transformative influence of a school master, the eponymous Chips, and, by inference, using it in a discussion of the transformative power of education does cast the perception of my comments on equality of access, linked with educational design and learning systems as transformative technologies, as being seen as both naïve and (in a more personal reading) makes me uncomfortably aware that some people might think I’m talking about myself as being the key catalyst of some sort. One of the nice things about being an academic is that you can have a discussion like this and not actually come to blows over it – we think and argue for a living, after all. But I find this dismissive and rude. If we’re not trying to educate people and transform them, then what the hell are we doing? Advocating inclusion and transformation shouldn’t be seen as grandstanding – it should be seen as our job. I don’t want to be the keystone, I want systems that work and survive individuals, but that individuals can work within to improve and develop – we know this is possible and it’s happening in a lot of places. There are, however, pockets of resistance: people who are using the same old approaches out of laziness, ignorance and a refusal to update for what appear to be philosophical reasons but have no evidence to support them.

Frankly, I’m getting a little irritated by people doubting the value of the volumes of educational research. If I was dealing with people who’d read the papers, I’d be happier, but I’m often dealing with people who won’t read the papers because they just don’t believe that there’s a need to change or they refuse to accept what is in there because of a perceived difficulty in making it work. (A colleague demanded a copy of one of our papers showing the impact of our new approaches on retention – I haven’t heard from him since he got it. This probably means that he’s chosen to ignore it and is going to pretend that he never asked.) Over coffee this morning, musing on this, it occurred to me that at the same time that we’re not getting the greatest amount of respect and love in the educational research community, we’re also worried about the trend towards MOOCs. Many of our concerns about MOOCs are founded in the lack of evidence that they are educationally effective. And I saw a confluence.

All of the educational researchers who are not able to sway people inside their institutions – let’s just ignore them and surge into the MOOCs. We can still teach inside our own places, of course, and since MOOCs are free there’s no commercial conflict – but let’s take all of the research and practice and build a brave new world out in MOOC space that is the best of what we know. We can even choose to connect our in-house teaching into that system if we want. (Yes, we still have the face-to-face issue for those without a bricks-and-mortar campus, but how far could we go to make things better in terms of what MOOCs can offer?) We’re transformers, builders and creators. What could we do with the infinite canvas of the Internet and a lot of very clever people, working with a lot of very other clever people who are also driven and entrepreneurial?

The MOOC community will probably have a lot to say about this, which is why we shouldn’t see this as a hijack or a take-over, and I think it’s helpful to think of this very much as a confluence – a flowing together. I am, not for a second, saying that this will legitimise MOOCs, because this implies that they are illegitimate, but rather than keep fighting battles with colleagues and systems that can defeat 40 years of knowledge by saying “Well, I don’t think so”, let’s work with people who have already shown that they are looking to the future. Perhaps, combining people who are building giant engines of change with the people who are being frustrated in trying to bring about change might make something magical happen? I know that this is already happening in some places – but what if it was an international movement across the whole sector?

Jinkies! (Sorry, the title ran to this and I get to use a picture of a t-shirt with Velma on it!)

The purpose of this is manifold:

- We get to build the systems that we want to, to deliver education to students in the best ways we know.

- We (potentially) help to improve MOOCs by providing strong theory to construct evidence gathering mechanisms that allow us to really get inside what MOOCs are doing.

- More students get educated. (Ok, maybe not in our host institutions, but what is our actual goal anyway?)

- We form a strong international community of educational researchers with common outputs and sharing that isn’t necessarily owned by one company (sorry, iTunesU).

- If we get it right, students vote with their feet and employers vote with their wallets. We make educational research important and impossible to ignore through visible success.

Now this is, of course, a pipe dream in many ways. Who will pay for it? How long will it take before even not-for-pay outside education becomes barred under new terms and conditions? Who will pay my mortgage if I get fired because I’m working on a deliberately external set of courses for students who are not paying to come to my institution?

But, the most important thing, for me, is that we should continue what has been proposed and work more and more closely with the MOOC community to develop exemplars of good practice that have strong, evidence-based outcomes that become impossible to ignore. Much as students use temporal discounting to procrastinate about their work, administrators tend to use a more traditional financial discounting when it comes to what they consider important. If it takes 12 papers and two years of study to justify spending $5,000 on a new tool or time spent on learning design – forget about it. If, however, MOOCs show strong evidence of improving student retention (*BING*), student attraction (*BING*), student engagement (*BING*) and employability – well, BINGO. People will pay money for that.

I’ve spoken before about how successful I had to be before I was tolerated in my pursuit of educational research and, while I don’t normally talk about it in detail because it smacks of hubris and I sincerely believe that I am not a role model of any kind, I hope that you will excuse me so that I can explain why I think it’s crazy as to how successful I had to be in order to become tolerated – and not yet really believed. To summarise, I’m in three research groups, I’ve brought in (as part of a group and individually) somewhere in the order of $0.5M in one non-ed research area, I’ve brought in something like $30-50K in educational research money, I’ve published two A journals (one CS research, one CS ed), two A conferences (both ed) and one B conference (ed/CS) and I have a faculty level position as an Associate Dean and I have a national learning and teaching presence. All of the things on that line – that’s 2012. 2011 wasn’t quite as successful but it wasn’t bad by any stretch of the imagination. I think that’s an unreasonably high bar to pass in order to be allowed the luxury of asking questions about what it is that we’re doing with learning and teaching. But if I can leverage that to work with other colleagues who can then refer to what we’ve done in a way that makes administrators and managers accept the real value of an educational revolution – then my effort is shared over many more people and it suddenly looks like a much better investment of my time.

This is more musing that mission, I’m afraid, and I realise that any amount of this could be shot down but I look forward to some discussion!

Vale, Neil Armstrong (or, What Happened to my Moon Base?)

Posted: August 27, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, armstrong, blogging, education, educational problem, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, moon, nasa, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, work/life balance Leave a commentNeil Alden Armstrong, the first human to set foot on the Moon, has left us at the age of 82. I don’t remember the moonwalk although, as a baby, I was placed in front of the television to ‘watch’ as, on July 21st, we walked on another world. Growing up, of course, it quickly became apparent that we didn’t go to the Moon anymore, the last walk being when I was 4ish. Apollo 17, the last mission, was in December, 1972, and the planned Apollos (out to 20) were scrubbed. Yes, we got Skylab up into orbit and that was really exciting, as were the docking missions, but it wasn’t THE MOON.

But we were still in space! After all, it was only 8 years later that we all watched as the Space Shuttles started to go into the sky. Well, we were in space. It was obvious that other countries were doing things as well (for those who didn’t grow up with this, it’s fair to say that the USA and USSR didn’t get on for a while so information sharing was limited and often heavily propagandised by both parties) but that glorious shuttle, climbing up into the sky, had taken the baton and we even (finally) managed to get a space station in orbit that was bigger than a breadbox. But, by Moon shot comparisons, it wasn’t quite in the same league.

Now, I’m not for a moment suggesting that space travel has been the best use of our time and money but, goodness, has it been inspirational! We’ve developed some amazing things along the way and we’ve learned a great deal about ourselves – one of which, sadly, is that the future that I am living is not the future that I thought I would inhabit.

Growing up, I made a number of assumptions, based on the talk of the time and the books I read (a lot of which were science fiction) and, looking back on it now, these ideas were very inspirational. Growing up in the England of the early-mid 70s (a cold, lean and unpleasant place) having heroes from space was an important thing for me to have. The messages from the real-life stories of achievement (we went to the Moon! We’re getting rid of smallpox! We’re pushing back disease!) were, and still are, an important part of me. Even where we had dystopia presented to us, it was in order to learn. (The Earth has finite resources, for example, so perhaps we should be living within our means a little better – this is the message of so many works from the mid-late 20th century.)

An Eagle Transporter from the UK television series Space:1999. Note almost complete lack of aerodynamic features, including wing-based control surfaces, because (wait for it) there is no air on the Moon!

But, of course, we have no moon base. We have carried out an incredible and technologically staggering feat to gently drop the new Mars explorer on Mars – but there are no people there. I’m not sure how many times we’ll go back there and my fear is that, within 10 years, we abandon that too. But we aren’t just losing space. A number of our achievements in the face of disease and social equality, for example, are being undermined by deliberate dissemination of disinformation and the shameful exploitation of fear and ignorance.

Sadly, at least some of the people who read this will scoff at the idea that we even went to the Moon. “You rube,” they’re thinking, “Everyone knows it was a giant hoax and cover-up.” The same thing applies to vaccines, where the human failing regarding probability and modelling comes to the fore and the fearful and anecdotal are treasured over the science. Don’t even get me started on the climate change denial movement.

Is this our fault? As scientists did we presume too much in our certainty and, after so many mistakes, have we earned this distrust? Frankly, while scientists have been responsible for some shameful acts of wilful destruction or negligence, I don’t think we deserve to be viewed in such a harsh light. What I believe we’re seeing is the snake oil merchant at its finest – preying on the weak, undermining reality for their own ends, looking into the near term future of the wallet rather than the long term future of us all.

What scares me is that we may be losing our knowledge. That the simplest of ideas in science, that you collect and observe evidence in order to allow you to confirm or contradict your hypotheses, is being overrun by a mad dash towards a certainty based on wilful ignorance where you only see the evidence that agrees with your hypothesis, after the fact, and truth be damned. Should we be spending the money required to go back to the Moon? Perhaps not as it is a lot of money and, goodness knows, we have things to spend it on. But if our reason for not going back to the Moon is that we lack the drive, the imagination, the tenacity or the vision to achieve it – then we are in serious trouble.

People sometimes ask me how many students I need to have in my classroom in order to deliver a lecture. I like to have 80-95%, of course, but my answer is always the same: one. I will not consider it a waste of my time if I spend an hour with a student discussing the ideas and sharing knowledge with them. I want my students to be imaginative, driven, to be able to hang on like a terrier as they search for the truth and to understand that the search for knowledge is important – so I have to try to live that. I have to live it all the time because, all too often, there are too many examples of people ignoring the truth for a comfortable lie, for being famous for being famous, for being famous for being thoughtlessly reactive (shock jock, anyone), for changing their minds for political expediency, for outright lying, and for only valuing quantities and dollars rather than people and knowledge.

What gets me out of bed in the morning is my own set of heroes: my wife, my friends, those in my family who have overcome adversity, the real educators who do their job because they have to and because of their deep and enduring relationship with knowledge, the stars in my firmament. I looked to my own heroes growing up and those heroes wouldn’t have let the world resemble “Silent Running”, “Soylent Green” or “The Omega Man” – they, like me, wanted our children to grow up in a better world. Those films of the 60s and 70s were the product of SF writers looking forward and saying “We don’t want this.” In the absence of vision, in the attack upon science and in the minimisation of majestic and inspirational events, we get ever closer to these stinking, diseased, dying worlds that should only ever exist in our nightmares.

The green in this still from Silent Running is, in theory, almost all of what is left of Earth’s greenery. Not very large, is it?

I grew up thinking that “Silent Running”, a movie where companies ordered the destruction the last of Earth’s biomass because it was too expensive to keep, was hyperbole – at most a cautionary tale. Now, every day, I get out of bed to try and educate a new generation of scientists so that we don’t accidentally or deliberately end up going over exactly that precipice. Thought is the greatest tool that we have and, like any tool, it can work for us and against us. Guiding thought along constructive paths is challenging and it always helps to have a large and visible goal to aim for: navigators need stars or ships get lost.

We need champions. We need champions so large that even our other champions look to them – we need ideas so beautiful and so huge and so captivating that the vast majority of people, when exposed to them, roll up their sleeves and say “I can help.” We need people for your children to aspire to be, because of what they did, not who they are. However, while we have many champions, the giant blazing comets that I had growing up are all dying or dead and it makes me very sad. Yes, there is incredible achievement going on and there are many, many great stories but what does the future look like to someone growing up now?

My future was full of moon bases, flying cars, leisure time, robots, everyone well fed, no war, gender and race equality – what’s our scorecard looking like?

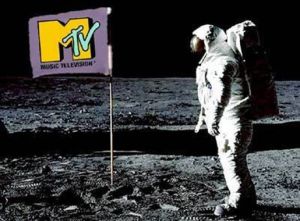

Soon there will be no-one left who walked on the moon. After 2099, there will probably be no-one alive when we did walk on the moon. What happens to the accounts of the Moon then? How long before it becomes a myth? How long before the real footage gets mixed up with Hollywood movies – or the MTV Logo becomes the 22nd century’s view of what happened on the Moon?

Of course, there is no real need to go back to the Moon. There are many other things that we can usefully do with that money and, ethically, we probably should. In terms of inspiration, it’s hard to beat, but that just makes it a challenge to find a problem that is equally big and put it together in a way that we can all see the rightness of it.

If you’ve read this far, thank you, but I have an additional favour to ask of you. This week, if possible, I’d like you to find an extra something, somewhere, that puts an extra champion into your life or into the life of someone else. It doesn’t have to be a person, it just has to be a star to set a course by. Something to look up to in high seas to know why you’re going where you’re going and that the risk is worth it. Have you told one of your living champions how much they mean to you? Have you made the time to share your (I know, precious) time and knowledge with someone else? Can you pin a picture of Hypatia to your pinboard? Rosa Parks? Jon Snow? Curie? Lister? Brunel? da Vinci? The SS Great Britain? Euler? Gauss? Florey? The Wrights? The 1902 Glider or the Wright Flyer 1? Crick/Watson/Franklin (bonus points if you have them in a wrestling ring wearing Luchador masks)? A Crab Canon? Telemann? Steve Kardynal?

“Reserve your right to think, for even to think wrongly is better than not to think at all,” Hypatia of Alexandria.

Have you taken your champion out of your head and told everyone else about them? When we landed on the Moon a vast number of us looked up and, for one moment, we all shared the same vision.

Neil Armstrong lived a good life, one that was useful and surprisingly humble given what he achieved and the position in which he found himself, but he’s gone now and we need more people and inspiration to fill the gap that he left. We need to look up once more.

Reflection on Work Load: I may have been too convincing

Posted: August 22, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, education, educational problem, higher education, teaching, time banking, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentI’m a bit of a hypocrite when it comes to taking my own advice on exercise. “Start easy,” I say, as I come back from injury with a fast 10 mile run. “Don’t over do it!” I admonish as I try to lift my own body weight in a gym. I have two knee surgeries, multiple calf strains and a torn plantar fascia to bear witness to this. For this, and many other reasons, I have a personal training for the gym stuff who I see once a week and a running partner who (facetiously) threatens to slap me if I run too hard or too far. I’m more scared of her than I am my personal trainer but don’t tell her that.

To fit everything in, I train in the gym at 6am on Wednesdays and, while this gives me a long day it allows me to get some good core and upper body work in to balance my legs and overall fitness – strength is useful in many ways as a day-to-day thing but balance, the other effect of good core strength, is incredibly useful and makes me a much better runner. I also take the opportunity to talk to someone who doesn’t work with me, isn’t related to me and knows what I do, but not in much detail. It’s very relaxing to talk to someone like that, especially when you have things on your mind.

Time Banking has been on my mind, as has my own time management, so I’ve talked a lot about making my life more effective, working less and working better, all those good things. So imagine my surprise when my trainer wrote to me asking if we could move sessions a little, if possible, as he’d been listening to what I’d been saying and realised that he’d been working reactively by not allowing himself enough time to plan and structure his day, especially as he’s now managing the gym I train at.

I’ve been thinking about changing away from the Wednesday 6 slot and this means that this is great timing for me. I’d like to keep training with him but I could train with someone else who doesn’t have his burdens or schedule quite easily and still have a really good experience – I’ve trained with other people before there, it’s a good gym. But what I really like is the thought process – contemplative and transformative.

Now, either this is the greatest con job that I’ve been privy to or I may have actually helped someone else to see a new way of thinking about their own life. Either way, there appears to be some knowledge transfer going on.

One person at a time. It’s slow but I can work with that. 🙂

Short and Sweet

Posted: August 21, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, community, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, Generation Why, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, workload 1 CommentWell, it’s official. I’ve started to compromise my ability to work through insufficient rest. Despite reducing my additional work load, chewing through my backlog is keeping me working far too much and, as you can tell from the number and nature of the typos in these posts, it’s affecting me. I am currently reorganising tasks to see what I can continue to fit in without compromising quality, which means this week a lot of e-mail is being sent to sort out my priorities.

This weekend, I’m sitting down to brainstorm the rest of 2012 and work out what has to happen when – nothing is going to sneak up on me (again) this year.

In very good news, we have 18 students coming back for the pilot activity of “Our students, their words” where we ask students who love ICT an important question – “what do you like and why do you think someone else might like it?” We’re brainstorming with the students for all of Friday morning and passing their thoughts (as research) to a graphic designer to get some posters made. This is stage 1. Stage 2, the national campaign, is also moving – slowly but surely. This is why I really need to rest: I’m getting to the point where it’s important that I am at my best and brightest. Sleeping in and relaxing is probably the best thing I can do for the future of ICT! 🙂

Rather than be a hypocrite, I’m switching to ultra-short posts until I’m rested up enough to work properly again.

See you tomorrow!

You Are Reading This on My Saturday

Posted: August 18, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, collaboration, community, education, educational problem, ethics, higher education, in the student's head, learning, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, workload 1 CommentAh, time zones. Because of these divisions of time, what publishes at 4:00am Saturday morning, Australian Central Standard Time, will be read by some of you on Friday. It is, however, important to realise that I am writing this on Friday evening, around 8:30pm, so that will help you to determine the context. You may not need it because my question is simple:

“What are you doing this weekend?”

If your answer is anything along the lines of spending time with the kids, sports, reading, writing the world’s worst screen play, going to the theatre, checking out the new cafe down on market – then bravo! If your answer is anything along the lines of “working” then, while I don’t doubt that you feel the genuine need to work, I do have to wonder about any weekend that features as much, if not more, work than a weekday.

I’m very guilty in this particular exchange. My wife has returned home after only two weeks away and I’ve already started to slip back into bad habits – not just doing work on weekends because I needed to, but assigning work to weekends as if they were weekdays.

See the difference there? It’s the difference between the reserve chute and the main chute, the emergency petrol in the jerry can to the fuel tank – it’s the difference between a temporary overload and workaholism.

I understand that many of you are under a great deal of pressure to perform, to put marks on a well-define chalkboard, to bring in money, to publish, to teach well, to do all of that and, right now, there aren’t enough hours in the week let alone the day. However, how you frame this mentally makes a big difference to how you continue to act… and I speak from bitter, bitter experience here.

Yesterday, I talked about things that I hadn’t achieved. Yet, today, I talk about taking the weekend off. No work. Minimal e-mail. Fun as a priority. Why?

Because the evidence clearly indicates that the solution to my problem lies in getting rest and sleep, not by reducing my ability to work effectively by working longer hours, less effectively. If I am to get the whole concept of student time management right, then it should work for me as well – as I’ve said numerous times. My dog food. Here’s a spoon. Eat it up.

Are you working so hard that you can’t focus? Is it actually taking you twice as long to get things done?

Then rest. Sleep in. Take a day off. By simple arithmetic, skipping a day to get back to higher efficacy is a good investment. Stop treating the weekends as conveniently quiet days where nobody bothers you – because everyone else has taken the day off.

That’s what I noticed when I started working weekends. The reason it was quieter is that, most of the time, no-one else was there. Ok, maybe they didn’t ‘achieve’ as much as I did – but how did they look? Were they grey, or jaundiced, tired and listless, possibly even angry and frustrated on Monday morning? Or were they bright and happy, full of weekend chatter? Did you, pale and wan, resent them for it?

Look, we all have to work weekends now and then and pull the occasional all-nighter, but making it a part of your schedule and, worse, cancelling your life in order to work because you tell yourself that this is a permanent thing? That’s not right. If it was right, your office would be full on weekends and at 10pm. (p.s. if that’s your company, and you’re working 80 hours a week, you’re terribly inefficient. Pass it on.)

Now, I’m going off to sleep. I will post some more over this weekend but most of it is scheduled. Let’s see if I can practice what I preach.

Talk to the duck!

Posted: August 17, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, grand challenge, higher education, principles of design, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, time banking, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentI’ve had a funny day. Some confirmed acceptances for journals and an e-mail from a colleague regarding a collaboration that has stalled. When I set out to readjust my schedule to meet a sustainable pattern, I had a careful look at everything I needed to do but I overlooked one important thing: it’s easier to give the illusion of progress than it is to do certain things. For example, I can send you a ‘working on it’ e-mail every week or so and that takes me about a minute. Actually doing something could take 4-8 hours and that’s a very large amount of time!

So, today was a hard lesson because I’ve managed to keep almost all of the balls in the air, juggling furiously, as I trim down my load but this one hurts. Right now, someone probably thinks that I don’t care about their project – which isn’t true but it fell into the tough category of important things that needs a lot of work to get to the next stage. I’ve sent an apologetic and embarrassed e-mail to try and get this going again – with a high prioritisation of the actual work – but it’s probably too late.

The project in question went to a strange place – I was so concerned about letting the colleague down that I froze up every time I tried to do the work. Weird but true and, ultimately, harmful. But, ultimately, I didn’t do what I said I’d do and I’m not happy.

So how can I turn this difficult and unpleasant situation into something that I can learn from? Something that my students can benefit from?

Well, I can remember that my students, even though they come in at the start of the semester, often come in with overheads and burdens. Even if it’s not explicit course load, it’s things like their jobs, their family commitments, their financial burdens and their relationships. Sometimes it’s our fault because we don’t correctly and clearly specify prerequisites, assumed knowledge and other expectations – which imposes a learning burden on the student to go off and develop their own knowledge on their own time.

Whatever it is, this adds a new dimension to any discussion of time management from a student perspective: the clear identification of everything that has to be dealt with as well as their coursework. I’ve often noticed that, when you get students talking about things, that halfway through the conversation it’s quite likely that their eyes will light up as they realise their own problem while explaining things to other people.

There’s a practice in software engineering that is often referred to as “rubber ducking”. You put a rubber duck on a shelf and, when people are stuck on a problem, they go and talk to the duck and explain their problem. It’s amazing how often that this works – but it has to be encouraged and supported to work. There must be no shame in talking to the duck! (Bet you never thought that I’d say that!)

I’m still unhappy about the developments of today but, for the purposes of self-regulation and the development of mature time management, I’ve now identified a new phase of goal setting that makes sense in relation to students. The first step is to work out what you have to do before you do anything else, and this will help you to work out when you need to move your timelines backwards and forwards to accommodate your life.

This may actually be one of the best reasons for trying to manage your time better – because talking about what you have to do before you do any other assignments might just make you realise that you are going to struggle without some serious focus on your time.

Or, of course, it may not. But we can try. We can try with personal discussions, group discussions, collaborative goal setting – students sitting around saying “Oh yeah, I have that problem too! It’s going to take me two weeks to deal with that.” Maybe no-one will say anything.

We can but try! (And, if all else fails, I can give everyone a duck to talk to. 🙂 )

Teaching Ethics in a Difficult World: Free Range and Battery Games

Posted: August 9, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, community, education, educational problem, ethics, free range games, games, higher education, in the student's head, principles of design, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, workload 2 Comments(Note, this is not a post about the existing game company, Free Range Games, although their stuff looks cool!)

I enjoy treating ethics or, to be more precise, getting the students to realise the ethical framework that they all live within. I’ve blogged before about this and how easy it is to find examples of unethical behaviour but, as we hear more stories about certain ‘game-related’ industries and the way that they teach testers, it becomes more and more apparent that we are reaching a point where the ethical burden of a piece of software may end up becoming something that we have to consider.

We’re already aware of the use of child labour in some products and people can make a decision not to shop at certain stores or buy certain products – but this requires awareness and tying the act to the brand.

In the areas I live in, it’s very hard to find a non-free range chicken, even in a chicken take-away shop (for various definitions of ‘free range’ but we pretty much do mean ‘neither battery nor force fed’) and eggs are clearly labelled. Does this matter to you? If so, you can make an informed decision. Doesn’t matter to you? Buy the cheapest or the tastiest or whichever other metric you’re using.

But what about games? You don’t have to look far (ea_spouse and the many other accounts available) to see that the Quality Assurance roles, vital to good games, are seeing a resurgence in the type of labour management that is rapidly approaching the Upton Sinclair Asymptote. Sinclair wrote a famous turn-of-the 20th Century novelisation of the conditions in the meat packing industry, “The Jungle”, that, apart from a rather dour appeal to socialism at the end, is an amazing read. It changed conditions and workers’ rights because it made these invisible people visible. Once again, as well apparently fall in love with the ‘wealth creators’ (an Australian term that is rapidly become synonymous with ‘robber baron’) all over again, we are approaching this despite knowing what the conditions are.

What I mean by this is that it is well known that large numbers of staff in the QA area in games tolerate terrible conditions – no job security, poor working conditions, malicious and incompetent management – and for what? To bring you a game. It’s not as if they are fighting to maintain democracy (or attack democracy, depending on what you consider to be more important) or staying up for days on end trying to bring the zombie infection under control. No, the people who are being forced into sweatboxes, occasionally made to work until they wet themselves, who are unceremoniously fired at ‘celebration’ events, are working to make sure that the people who wrote your game didn’t leave any unexplained holes in the map. Or that, when you hit a troll with an axe, it inflicts damage rather than spontaneously causing the NyanCat video to play on your phone.

This discussion of ethics completely ignores the ethics of computer games that demean or objectify women, glorify violence or any of the ongoing issues. Search for ethics of video games and it is violence and sexism that dominates the results. It’s only when you start searching for “employee abuse video game” that you start to get hits. Here are some quotes from one of them.

It seems as though the developers of L. A. Noire might have been under more pressure themselves than any of the interrogated criminals in their highly praised crime drama. Reports have surfaced about employees being forced to work excruciating hours, in some cases reaching 120 hour weeks and 22 hour days. In addition, a list has been generated of some 130 members of the Australian-based Team Bondi, the creators of L. A. Noire, whose names have been omitted from the game’s own credits.

…

On the subject of the unprecedented scope of the project for Australian developers, McNamara replied, “The expectation is slightly weird here, that you can do this stuff without killing yourself; well, you can’t, whether it’s in London or New York or wherever; you’re competing against the best people in the world at what they do, and you just have to be prepared to do what you have to do to compete against those people. The expectation is slightly different.”

The saddest thing, to me, is that everyone knows this. The same people who complain on my FB feed back how overworked they are and how little they see their family then go out and buy games that have been produced in electronic sweatshops. You didn’t buy L. A. Noire? Rockstar San Diego are on the “overworking staff” list for “Red Dead Redemption” and the “not crediting everyone” for “Manhunt 2”. (That last one might not be so bad!)

Everyone talks about the crunch as if it’s unavoidable. Well, yes , it is, if you intend to work people to the crunch. We’ve seen similar argument for feedlot meat production, battery animals and, let’s not forget, that there have always been “excellent” reasons for slavery in economic and social terms.

This is one of the hardest things to talk about to my students because they’re not dumb. They read, often more widely than I do in these areas. They know that for all my discussions of time management and ethics, if they get a certain kind of job they will work 7 days a week, 10-14 hours a day, in terrible conditions and maybe, just maybe, if they sell their soul enough they can get a full-time job, rather than being laid off indiscriminately. They know that the message coming down from these companies is “maximum profit, minimum spend” and, of course, most of these game companies aren’t profitable so that’s less about being mercenary and more about survival.

But, given that these products are not exactly… essential (forgive me, Deus Ex!), one has to wonder whether terms like ‘survival’ have any place in this discussion. Is it worth nearly killing people, destroying their social lives and so one, to bring a game to market? People often say “Well, they have a choice” and, in some ways, I suppose they do – but in an economic market where any job is better than job, and people can make decisions at 15 that lead to outcomes they didn’t expect at 25, this seems both ungenerous and thoughtless.

Perhaps we need the equivalent of a ‘Free Range/Organic’ movement for games: All programmers and QA people were officially certified to have had at least 8 hours sleep a night, with a minimum break of 50 hours every 6 days and were kept at a maximum density of 2 programmers per 15 square metres, in a temperature and humidity controlled environment that meets recognised comfort standards.

(Yeah, I didn’t include management. I think they’re probably mostly looking after themselves on that one. 🙂 )

Then you can choose. If it matters to you, buy 21st century Labour Force Games – Ethically and sustainably produced. If it doesn’t matter, ignore it and game on.

Two Speeds: Nothing and Ultra High Speed

Posted: August 8, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, higher education, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, workload 1 CommentShort post today. I’m reminded that, even with the best view of what you have to do, any time that you have in your calendar to do things can easily disappear when the unexpected strikes. I had this week planned as a reasonably paced week, with some paper writing. Now I’m looking at a week where I have one unscheduled 30 minute period until Friday evening.

Was this poor planning? No, I had my calendar planned with preparation time and all days were sitting under at my 70% scheduled limit, well under, in fact, because I wanted to allow as much drop-in time as possible for my students. However, now the time has filled up and, yet, all of my deadlines for this week still apply – plus some more on top.

It’s a reminder that stuff happens sometimes and, as we (eventually) start writing the time banking papers, it’s important to remember how easy it is to go from “everything’s cool” to “oh no, my brain is on fire!”. Now I have a lot of experience in handling brain fire but, even so, it’s that nasty little shock that means that there will be no early nights for me until Sunday. This is a surge week, a stretch week, so the usual 45 hour upper limit (the guideline to see if I can get everything done) is on hiatus but will be reset for Monday.

Now this is important because I have, so far, been able to get everything done within the time that I’ve been allocating, I’ve been more relaxed and I’ve been more effective. Today wasn’t the best day in some ways because the wheels had started to fall off and most of my day was spent planning in one part of my head while working with the other.

I see students hit this point a lot and an important part of my job is talking them down from the ledge, in effect. It’s very hard for people who are working o hard, and not getting everything done, to think that working fewer hours will allow them to achieve their goals. So far, I’ve been able to do it, as long as I am open to the occasional burst of week but, at the moment, I’m sitting the limit at 1 week.

We’ll see if that works!

Whackademia: Anectopia, More Like. (A Rather Opinionated Review)

Posted: August 4, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: blogging, education, ethics, higher education, richard hil, thinking, whackademia, work/life balance, workload 5 CommentsI recently posted about some of the issues that we face in Academia and, being honest, they aren’t small problems and they aren’t limited to one locale or country. You may also recall that I wrote a summary of a radio interview with Richard Hil, the author of Whackademia and I said that I’d write more on Richard’s thoughts when I finished the book.

Hmm. Be careful what you commit to. This book is long on moan but short on solution. But, to explain this, I must be long on moan – please forgive me. I realise that some of you may feel that I am a heavily corporatised shill, who the book is targeted against, and therefore unworthy to comment on this so caustically. Believe me when I say that I believe that my role is to hold my integrity in my job while trying to achieve a better environment in which all of us can perform our jobs – and I believe that anyone who knows me and what I do would agree with that. If I am a shill, then I am the shill that you want on your side because it would be harder to find anyone more committed to the purity of learning and teaching and the world enriching nature of research. Yes, I am an idealist who walks with the devil sometimes, but my soul is still my own.

There were a couple of points in the original radio interview when I would have preferred that Hil go into more detail, or provide some more supporting evidence. I can honestly say that my desire for some more substance has still not been met.

There is no doubt that there are problems, that rampant managerialism is not helping, that a review of the sector in the light of a reduced commitment to funding from the government is important. But what is presented in Hil’s book is a stream of unattributed complaint, whinging and, above all, a constant litany of admissions of unethical behaviour from Hil’s interview participants – with the defence that they were told to comply so, of course, they did. Rather than interpreting this as a group of noble warriors being forced to bend their heads before a cruel and unjust overlord, I read this as the words of people who, having one of the most important jobs in the world, took the easier path.

Do I think that I’ve ever assigned a mark to a student that they didn’t earn?

No. No, I don’t. This is at odds with any number of Hil’s interviewees who freely admitted to fixing marks when asked to, bending over in the face of the administrative wind and, then, having the hide to complain about slipping standards and lack of freedom. I don’t interpret the monitoring levels of academic progress and student progressions rates as a requirement to pass people, I regard it as a way of ensuring that we fairly advertise what is required to pass our courses, that we provide opportunities for students to display their ability and that we focus on education – taking difficult things and conveying them to students.

Show me someone who is proud that their course is so tough that 90% of students fail it and, frankly, I think that they can call themselves anything they like, as long as the word teacher or educator isn’t used. I could fail 100% of students who take my course – gaze upon my works, for there are none as smart as I! This isn’t academic integrity, this is hubris.

Why am I so disappointed in this work? Because I agree with a number of Hil’s points but he presents the weakest, anecdotal means for supporting it. “Whackademia” is eminently dismissible and this is a terrible thing, as it makes the genuine problems that are raised easier to dismiss.

I am still desperately searching for a solution, a proposal from Hil that is more tangible than a fragmented wish list and anything other than his journey through a poisonous and frustrated Anectopia – light on fact but dripping with salacious, unsubstantiated detail. I really shouldn’t be surprised. If you read the contents page, you’ll see that Chapter 7 is entitled “Enough Complaint: now what?” on page 193. Given that the book is over by page 230, that’s a lot of complaint to solution! (Note to self, check the ratio in this post…)

Let me give you some quotes:

“Additionally, older interviewees argued that younger academics were far more likely to have adopted today’s regulatory rationalities, in contrast to more seasoned academics who are perhaps more resistant to the new order. Whether or not this is true is less important than the fact that, to survive and thrive in the current tertiary culture, certain compromises may have to be made – even if this feels at times like putting one’s soul out to tender.” p91

Whether or not this is true? Hang on, truth is optional in this sentence?

Let me put that quote back together with the qualifiers and questionable modifiers highlighted.

“Additionally, older interviewees argued that younger academics were far more likely to have adopted today’s regulatory rationalities, in contrast to more seasoned academics who are perhaps more resistant to the new order. Whether or not this is true is less important than the fact that, to survive and thrive in the current tertiary culture, certain compromises may have to be made – even if this feels at times like putting one’s soul out to tender.”

“faculties – sometimes referred to as ‘corporate silos'” p87

“These sorts of observations might be dismissed out of hand by today’s university managers as elitist, sentimental drivel, born of resentment of the new corporate reality. Well, if indeed these reflections are drivel then they are shared by all but one of the ten or so older professors I interviewed for this book.”

Hil’s book is identified on the cover as a searing exposé from an insider but, as someone who is also on the inside, it appears that the insides that we inhabit are distinctly different. No doubt, there are people inside my own institution who would read Hil’s words and shiver with the rightness of his words: “Yes, I am being pushed around!”, “Yes, I have to take shortcuts because big bad Admin makes me!”, “Yes, students are just sometimes too stupid for my wonderful course and I should be allowed to fail 80% of them!” But I’d disagree with them as much as I disagree with Hil.

The greatest disappointment I ever feel is when someone squanders their opportunities and their gifts, especially when they destroy opportunities for other people. In this case, not only has Hil wasted his spot in the sun, he has made it harder for a more thoughtful and constructive book to be written as his work, writ large in the media and read widely, will control and shape the debate for some time to come.

Again, for shame, sir.