Today, As I Was Crawling Across the Floor…

Posted: June 10, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, education, educational problem, games, higher education, principles of design, puzzles, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, zombies 3 CommentsAs I believe I’ve already mentioned, I play a number of board games but, before you think “Oh no, not Monopoly!”, these are along the lines of the German-style board games, games that place some emphasis on strategy, don’t depend too heavily on luck, may have collaborative elements (or an entirely collaborative theme), tend not to be straight war games and manage to keep all the players in the game until the end. Notably, German-style board games don’t have to be German! While some of the ones that I enjoy (Settlers of Cataan, Ticket to Ride and Shadows Over Camelot) are European, a number are not (Arkham Horror, Battlestar Galactica and Lords of Waterdeep). A number of these require cooperative and collaborative play to succeed – some have a traitor within.

I have discussed these games with students on a number of occasions as many students have no idea that such games exist. The idea of players working together against a common enemy (Arkham Horror) appeals to a lot of people, especially as it allows you to share success. One of the best things about games that are well-designed to reward player action and keep everyone in the game is that the tension builds to a point a final victory gives everyone fiero – that powerful surge of joy.

Now, while there are many games out there, I decided to go through the full game design process to get my head around the components required to achieve a playable game. I’ve designed some games before and, after a brief time spent playing them, I’ve left most of them back on the shelf. Why? Poor game design, generally. As a writer, I have a tendency to think of stories and to run narrative in my head – in game terms, this is only one possible passage through the game. One of the strengths of computer games such as Deus Ex is the ability to play multiple times and get something new out: to shake up the events and run it in your order, forming a new narrative. (In DE, technically, you were on rails the whole time, the strength of the game is in the illusion of free will.)

Why is it important for me to try and design a good game? Because it requires a sound assessment of what is required, reflection upon how I can model a situation in a game, good design, solid prototyping, testing, feedback, revision, modification, re-testing, thought, evaluation and then more and more refinement. From a methodological point of view, my question to myself is “Can I build a game that is worth playing based on a general sketch of the problem, a few good ideas and then a solid process to allow me to build game features in the way that I would build code features?”

Right now I’m in the requirements gathering phase and this is proving to be very interesting. I’m working on a Zombie game (oh no, not another one) but I want to have a three-stage game where the options available to players, resources and freedom of action, change dramatically during each stage. I want it to be based in London. I want to allow for players to develop their characters as they play through a given game. I want player actions to have a lasting impact in the game, for decisions to matter. I want the game to generate a different board and base scenario set every time, to prevent players learning a default strategy. I want the whole thing to run, as a board game, in the German style. I want the instructions to fit onto 8 A4 pages – with pictures.

(I should note that I’ve been playing games for a long time and made a lot of notes about rules and mechanics that I like, so this has all formed part of my requirements gathering, but I’m not trying to put a new skin on an old game – I’m trying to create something interesting that is also not a blatant rip-off. Also, yes, I know that there are already a lot of zombie games out there. That isn’t the point.)

I’ve been crawling the web for pictures of London, layouts, property values, building types and other things to get London into my head. Because the board has to change every time, and I can’t use computer generation, I need a modular board structure. That, of course, requires that the modules make sense and feel like London, and that the composition of these modules also makes sense. I need the size of the board to make the players work for their victories and not make victory too easy or too hard to attain. (So, I’m building bounds into the modularity and composition that I can tune based on what happens in play testing.)

I knew this but my research nailed it as a requirement: London is about as far away from being a grid layout as you can get, with a river snaking through it. Because of this, and my randomisation and modularity requirements, I had to think about a system that allowed me to put the elements together but that didn’t make London look like New York. Instead, I’ve opted for a tiled layout based on hexagons. They tesselate nicely, you can’t run in straight lines, and you can’t see further than the side of one hex, which reflects the problems of working in London without having to force someone to copy out a section of the London map with all of its terrible twists and turns.

The other thing I really wanted to know was “How fast do zombies move?” and, rather than just look it up, I’ve spent a bit of this afternoon shambling around the house and timing myself to see what the traditional “slow” zombie does. Standard walking and running are easy (I have a good feel for those figures) but then I thought about that stalwart of zombie movies – the legless crawler. So, in the interests of research, I measured off a 10m course and dragged myself across the floor only using my arms. Then I added a fudge factor to account for the smoothness of the floor and, voila, a range of speeds that tell me how long zombies will take to move across my maps.

Why do I need to do this? Because I’ve never done it before. From now on, if someone asks me what the estimated speed of a legless zombie is on a level surface, I can say “Oh, about 0.25m/s” and really stop the conversation at the Vice Chancellor’s cocktail party.

Requirements gathering, around a problem specification, is a vital activity because if it’s done properly then you gain more and more understanding of the problem and, even though initially the questions seem to explode, you can move to a point that you have answered most of the important questions. By the time I’ve finished this stage, I should have refined my problem statement into a form that allows me to write the proper design and then build the first prototype without too many further questions. I should have the base rules down in a form that I can give to somebody and see what they do.

By doing this, I’m practising my own Software Engineering skills in a very different way, which makes me think about them outside of the comfortable framework of a programming language. Students often head off to start writing code because it’s easier to sit and write code that might work, instead of spending the time doing the far more difficulty activities of problem specification, requirements gathering, specification refinement and full design. I don’t get much of a chance to work on commercial software these days, so a zombie game on the weekends is an unusual, if rewarding, way to practice these skills.

Sliding across the floor is murder on the knees, though…

Last Lecture Blues

Posted: June 7, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, education, educational problem, feedback, games, Generation Why, higher education, in the student's head, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a commentI delivered the last lecture, technically the review and revision lecture, for my first year course today. As usual, when I’ve had a good group of students or a course I enjoy, the relief in having reduced my workload is minor compared to the realisation that another semester has come to an end and that this particular party is over.

Today’s lecture was optional but we still managed to get roughly 30% of the active class along. Questions were asked, questions were discussed, outline answers were given and then, although they all say and listened until I’d finished a few minutes late, they were all up and gone. The next time I’ll see most of them is at the exam, a few weeks from now. After that? It depends on what I teach. Some of these students I’ll run into over the years and we’ll actually get to know each other. Some may end up as my honours or post-graduate students. Some will walk out of the gates this semester and never return.

Now, hear me out, because I’m not complaining about it, but this is not the easiest job in the world. Done properly, education requires constant questioning, study, planning, implementing, listening, talking and, above all, dealing with the fact that you may see the best student you ever have for a maximum of 6 months. It is, however, a job that I love, a job that I have a passion for and, of course, in many ways it’s a calling more than a job.

One of the things I’ve had a chance to reflect on in this blog is how much I enjoy my job, while at the same time recognising how hard it is to do it well. Many times, the students I need to speak to most are those who contact me least, who up and fade away one day, leaving me wondering what happened to them.

At the end of the semester, it’s a good time to ask myself some core questions and see if I can give some good answers:

- Did I do the best job that I could do, given the resources (structures, curriculum, computers etc) that I had to work with?

- Did I actively seek out the students who needed help, rather than just waiting for people to contact me?

- Did I look for pitfalls before I ran into them?

- Did I look after the staff who were working with or for me, and mentor them correctly?

- Did I try to make everything that I worked with an awesome experience for my students?

This has been the busiest six months of my life and one of my joys has been walking into a lecture theatre, having written the course, knowing the material and losing myself in an hour of interactive, collaborative and enjoyable knowledge exchange with my students. Despite that, being so busy, sometimes I didn’t quite have the foresight that I should had had and my radar range was measured in days rather than weeks. Don’t get me wrong, everything got done, but I could have tried to locate troubled students more actively, and some minor pitfalls nearly got me.

However, I think that we still delivered a great course and I’m happy with 1, 4 and 5. I aimed for awesome and I think we hit it fairly often. 2 and 3 needed work but I’ve already started making the required changes to make this better.

On reflection, I’d give myself an 8ish/10 but, of course, that’s not enough. Overall, in the course, because of the excellent support from my co-lecturer and my teaching staff, the course itself I’d push up into the 9-pluses. I, however, should be up there as well and right now, I’m too busy.

So, it’s time for some rebalancing into the new semester. Some more structure for identifying problems students. Looking at things a little earlier. And aiming for an awesome 10/10 for my own performance next semester.

To all my students, past and present, it’s been fantastic. Best of luck with your exams!

Eating Your Own Dog Food (How Can I Get Better at Words with Friends?)

Posted: June 4, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, design, eat your own dog food, eating your own dog food, eating your own dogfood, education, educational problem, games, higher education, in the student's head, learning, measurement, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, tools 1 CommentI am currently being simultaneously beaten in four games of Words with Friends. This amuses me far more than it bugs me because it appears that, despite having a large vocabulary, a (I’m told) quick wit and being relatively skilled in the right word in the right place – I am rather bad at a game that should reward at least some of these skills.

One of the things that I dislike, and I know that my students dislike, is when someone stands up and says “To solve problem X, you need to take set of actions S.” Then, when you come to X, or you find that person’s version of a solution to X, it’s not actually S that is used. It’s “S-like” or “S-lite” or “Z, which looks like an S backwards and sounds like it if you’re an American with a lisp.”

There’s a term I love called “eating your own dog food” (Wikipedia link) that means that a company uses the products that it creates in order to solve the problems for which a customer would buy their products. It’s a fairly simple mantra: if you’re making the best thing to solve Problem X, then you should be using it yourself when you run across Problem X. Now,of course, a company can do this by banning or proscribing any other products but this misses the point. At it’s heart, dogfooding means that, in a situation where you are free to choose, you make a product so good that you would choose it anyway.

It speaks to authenticity when you talk about your product and it provides both goals and thinking framework. The same thing works for education – if I tell someone to take a certain approach to solve a problem, then it should be one that I would use as well.

So, if a student said to me “I am bad at this type of problem,” I’d start talking to them to find out exactly what they’re good and bad at, get them to analyse their own process, get them to identify some improvement strategies (with my guidance and suggestions) and then put something together to get it going. Then we’d follow up, discuss what happened, and (with some careful scaffolding) we’d iteratively improve this as far as we could. I’d also be open to the student working out whether the problem is actually one that they need to solve – although it’s a given that I’ll have a strong opinion if it’s something important.

So, let me eat my own dog food for this post, to help me get better at Words with Friends, to again expose my thinking processes but also to demonstrate the efficacy of doing this!

Step 1: What’s the problem?

So, I can get reasonable scores at Words with Friends but I don’t seem to be winning. Words with Friends is a game that rewards you for playing words with “high value” tiles on key positions that add score multipliers. The words QATS can be worth 13 or 99 depending on where it is placed. You have 7 randomly selected tiles with different letters, and a range of values for letters in a 1:1 association, but must follow strict placement and connection rules. In summary, a Words with Friends game is a connected set of tiles, where each set of tiles placed must form a valid word once set placement is complete, and points are calculated from the composition and placement of the tiles, but bonus spaces on the board only count once. The random allocation of letters means that you have to have a set of strategies to minimise the negative impact of a bad draw and to maximise the benefit of a good draw. So you need a way of determining the possible moves and then picking the best one.

Some simple guidelines that help you to choose words can be formed along the lines of the number of base points by letter (so words featuring Q, X or J will be worth more because these are high value letters), the values of words will tend to increase as the word length increases as there are more letters with values to count (although certain high value letters cannot be juxtaposed – QXJJXWY is not a word, sadly), but both of these metrics are overshadowed by the strategic placement of letters to either extend existing words (allowing you to recount existing tiles and extending point 2) or to access the bonus spaces. Given that QATS can be worth 99 points as a four-letter word if played in the right place, it might be worth ignoring QUEUES earlier if think you can reach that spot.

Step 2: So where is my problem?

After thinking about my game, I realised that I wasn’t playing Words with Friends properly, because I wasn’t giving enough thought to the adversarial nature of the occupancy of the bonus spaces. My original game was more along the lines of “look at letters, look at board, find a good word, play it.” As a result, any occupancy of the bonus spaces was a nice-to-have, rather than a must-have. I also didn’t target placement that allowed me to count tiles already on the board and, looking at other games, my game is a loose grid compared to the tight mesh that can earn very large points.

I’m also wasn’t thinking about the problem space correctly. There are a fixed number of tiles in the game, with known distribution. As tiles are played, I know how many tiles are left and that up to 14 of them are in my and my opponent’s hand. If I know how many tiles there are of each letter, I can play with a reasonable idea of the likelihood of my opponent’s best move. Early on, this is hard, but that’s ok, because we can both play in a way that doesn’t give a bonus tile advantage. Later on, it’s probably more useful.

Finally, I was trying to use words that I knew, rather than words that are legal in Words with Friends. I had no idea that the following were acceptable until (at least once out of desperation) I tried them. Here are some you might (nor might now) know: AA, QAT, ZEE, ZAS, SCARP, DYNE. The last one is interesting, because it’s a unit of force, but BRIX, a unit used to measure concentration (often of sugar) isn’t a legal word.

So, I had three problems, most of which relate to the fact that I’m more used to playing “Take 2” (a game played with Scrabble tiles but no bonus spaces) than “Scrabble” itself, where the bonus spaces are crucial.

Step 3: What are the strategies for improvements?

The first, and most obvious, strategy is to get used to playing in the adversarial space and pay much closer attention to which bonus spaces I leave open in my play and to increase my recounting of existing tiles. The second is to start keeping track of tiles that are out and play to the more likely outcome. Finally, I need to get a list of which words are legal in Words with Friends and, basically, learn them.

Step 4: Early outcomes

After getting thrashed in my first games, I started applying the first strategy. I have since achieved words worth over 100 points and, despite not winning, the gap is diminishing. So this appears to be working.

The second and the third… look, it’s going to sound funny but this seems like a lot of work for a game. I quite like playing the best word I can think of without having to constrain myself to play some word I’m never going to actually use (when we’re up to our elbows in aa, I will accept your criticism then) or sit there eliminating tiles one-by-one (or using an assistant to do it). Given that I’m not even sure that this is the way people actually play, I’m probably better off playing a lot of games and naturally picking up words that occur, rather than trying to learn them all in one go.

Of course, if a student said something along the last lines to me, then they’re saying that they don’t mind not succeeding. In this case, it’s perfectly true. I enjoy playing and, right now, I don’t need to win to enjoy the game.

Just as well really, I think I’m about to lose four games within a minute of each other. That’s four in a row – pity, if there were three of them I could do a syzygy joke.

Step 5: Discussion and Iteration

So, here’s the discussion and my chance to think about whether my strategies need modification to achieve my original goal. Now, if I keep that goal at winning, then I do need to keep iterating but I have noticed that with a simple change of aiming more a the bonuses, I get a good “Yeah” from a high points word that probably won’t be matched by winning a game.

To wrap up, having looked at the problem, thought through it and make some constructive suggestions regarding improvement, I’ve not only improved my game but I’ve improved my understanding and enjoyment of the activity. I feel far more in control of my hideous performance and can now talk to more people about other ways to improve that maintain that enjoyment.

Now, of course, I imagine that a million WwF players are going to jump in and say “nooooo! here’s how you do it.” Please do so! Right now I’m talking to myself but I’d love some guidance for iterative improvement.

Got Vygotsky?

Posted: April 25, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: Csíkszentmihályi, curriculum, design, education, flow, games, higher education, learning, principles of design, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, tools, vygotsky, Zone of proximal development, ZPD 4 CommentsOne of my colleagues drew my attention to an article in a recent Communications of the ACM, May 2012, vol 55, no 5, (Education: “Programming Goes to School” by Alexander Repenning) discussing how we can broaden participation of women and minorities in CS by integrating game design into middle school curricula (Thanks, Jocelyn!). The article itself is really interesting because it draws on a number of important theories in education and CS education but puts it together with a strong practical framework.

There’s a great diagram in it that shows Challenge versus Skills, and clearly illustrates that if you don’t get the challenge high enough, you get boredom. Set it too high, you get anxiety. In between the two, you have Flow (from Csíkszentmihályi’ s definition, where this indicates being fully immersed, feeling involved and successful) and the zone of proximal development (ZPD).

Which brings me to Vygotsky. Vgotsky’s conceptualisation of the zone of proximal development is designed to capture that continuum between the things that a learner can do with help, and the things that a learner can do without help. Looking at the diagram above, we can now see how learners can move from bored (when their skills exceed their challenges) into the Flow zone (where everything is in balance) but are can easily move into a space where they will need some help.

Most importantly, if we move upwards and out of the ZPD by increasing the challenge too soon, we reach the point where students start to realise that they are well beyond their comfort zone. What I like about the diagram above is that transition arrow from A to B that indicates the increase of skill and challenge that naturally traverses the ZPD but under control and in the expectation that we will return to the Flow zone again. Look at the red arrows – if we wait too long to give challenge on top of a dry skills base, the students get bored. It’s a nice way of putting together the knowledge that most of us already have – let’s do cool things sooner!

That’s one of the key aspects of educational activities – not they are all described in terms educational psychology but they show clear evidence of good design, with the clear vision of keeping students in an acceptably tolerable zone, even as we ramp up the challenges.

One the key quotes from the paper is:

The ability to create a playable game is essential if students are to reach a profound, personally changing “Wow, I can do this” realization.

If we’re looking to make our students think “I can do this”, then it’s essential to avoid the zone of anxiety where their positivity collapses under the weight of “I have no idea how anyone can even begin to help me to do this.” I like this short article and I really like the diagram – because it makes it very clear when we overburden with challenge, rather than building up skill and challenge in a matched way.

Card Shouting: Teaching Probability and Useful Feedback Techniques by… Yelling at Cards

Posted: April 5, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: card shouting, education, feedback, fiero, games, higher education, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, tools 2 CommentsI introduced a teaching tool I call ‘Card Shouting’ into some of my lectures a while ago – usually those dealing with Puzzle Based Learning or thinking techniques. What does Card Shouting do? It demonstrates probability, shows why experimental construction is important and engages your class for the rest of the lecture. So what is Card Shouting?

(As a note, I’ve been a bit rushed today and I may not have put this the best way that I could. I apologise for that in advance and look forward to constructive suggestions for clarity.)

Take a standard deck of cards, shuffle it and put it face down somewhere where the class can see it. (You either need very big cards or a document camera so that everyone can see this in a large class. In a small class a standard deck is fine.)

Then explain the rules, with a little patter. Here’s an example of what I say: “I’m sick and tired of losing at Poker! I’ve decided that I want to train a pack of cards to give me the cards I want. Which ones do I want? High cards, lots of them! What don’t I want? Low cards – I don’t want any really low cards.”

Pause to leaf through the deck and pull out a Ace, King and Queen. Also grab a 2,3 and 4. Any suit is fine. Hold up the Ace, King and Queen.

“Ok, these guys are my favourites. What I’m going to do, after this, is shuffle everything back in and draw a card from the top of the deck and flip it up so you can see it. If it’s one of these (A, K, Q), I want to hear positive things – I want ‘yeahs!’ and applause and good stuff. But if it’s one of these (hold up 2,3 and 4) I want boos and hisses and something negative. If it’s not either – well, we don’t do anything.” (Big tip: put a list of the accepted positive and negative phrases on the board. It’s much easier that having to lecture people on not swearing)

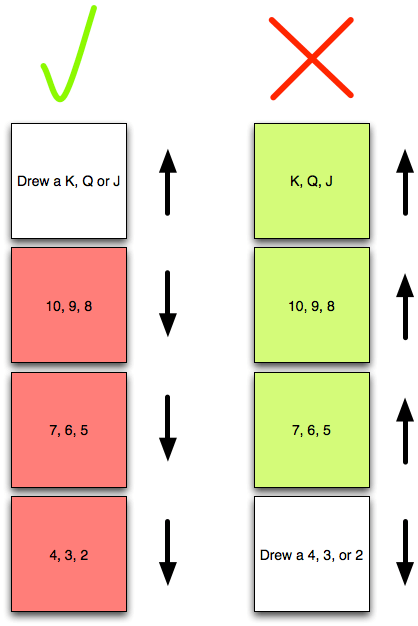

“Let’s find out what works best: praise or yelling- but we’re going to have measure our outcomes. I want to know if my training is working! If I draw a bad card and abuse it, I want to see improvement – I don’t want to see one of the bad cards on the next draw. If I draw a good card, and praise it, I want the deck to give me another good card – if it’s lower than a J, I’ve wasted my praise!” Then work through with the class how you can measure positive and negative reaction from the cards – we’ve already set up the basis for this in yesterday’s post, so here’s that diagram again.

In this case, we record a tick in the top left hand box if we get a good card and, after praising it, we get another good card. We put a tick in top right hand box if we draw a bad card, abuse the deck, and then get anything that is NOT a bad card. Similarly for the bottom row, if we praise it and the next card is not good, we put a mark in the bottom left hand box and, finally, if we abuse the card and the next card is still bad, we record a mark in the bottom right hand box.

Now you shuffle and start drawing cards, getting the reactions and then, based on the card after the reaction, record improvement or decline in the face of praise and abuse. If you draw something that’s neither good NOR bad to start with – you can ignore it. We only care about the situation when we have drawn a good or a bad card and what the immediate next card is.

The pattern should emerge relatively quickly. Your card shouting is working! If you get a card in the bad zone, you shout at it, and it’s 3 times as likely to improve. But wait, praise doesn’t do anything for these cards! You can praise a card and, again, roughly 3 times as often – it gets worse and drops out of the praise zone!

Not only have we trained the deck, we’ve shown that abuse is a far more powerful training tool!

Wait.

What? Why is this working? I discussed this in outline yesterday when I pointed out it’s a commonly held belief that negative reinforcement is more likely to cause beneficial outcome based on observation – but I didn’t say why.

Well, let’s think about the problem. First of all, to make the maths easy, I’m going to pull the Ace out of the deck. Sorry, Ace. Now I have 12 cards, 2 to K.

Let me redefine my good cards as J, Q, K. I’ve already defined my bad cards as 2, 3, 4. There are 12 different card values overall. Let me make the problem even simpler. If we encounter a good card, and praise it, what are the chances that I get another good card? (Let’s assume that we have put together a million shuffled decks, so the removal of one card doesn’t alter the probabilities much.)

Well, there are 3 good card values, out of 12, and 9 card values that aren’t good – so that’s 9/12 (75%) chance that I will get a not good card after a good card. What about if I only have 12 cards? Well, if I draw a K, I now only have the Q and the J left in my good card set, compared to 9 other cards. So I have a 9/11 chance of getting a worse card! 75% chance of the next card being worse is actually the best situation.

You can probably see where this is going. I have a similar chance of showing improvement after I’ve abused the deck for giving me a bad card.

Shouting at the cards had no effect on the situation at all – success and failure are defined so that the chances of them occurring serially (success following success, failure following failure) are unlikely but, more subtly, we extend the definition of bad when we have a good card – and vice versa! If we draw any card from 5 to 10 normally, we don’t care about it, but if we want to stay in the good zone, then these 6 cards get added to the bad cards temporarily – we have effectively redefined our standards and made it harder to get the good result. Here’s a diagram, with colour for emphasis, to show the usually neutral outcomes are grouped with the extreme.. No wonder we get the results we do! The rules that we use have determined what our outcome MUST look like.

So, that’s Card Shouting. It seems a bit silly but it allows you to start talking about measurement and illustrate that the way you define things is important. It introduces probability in terms of counting. (You can also ask lots of other questions like “What would happen if good was 8-K and bad was 2-7?”)

My final post on this, tomorrow, is going to tie this all together to talk about giving students feedback, and why we have to move beyond simple definitions of positive and negative, to focus on adding constructive behaviours and reducing destructive behaviours. We’re going to talk about adding some Kings and removing some deuces. See you then.

SIGCSE First night, Workshop: CS Unplugged!

Posted: March 2, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: design, education, games, higher education, sigcse, teaching, teaching approaches, tools 1 CommentGot back from the first workshop a couple of hours ago, Workshop 9: Computer Science Unplugged, Robotics and Research Activities, Tim Bell, Daniela Marghitu and Lynn Lambert. Daniela couldn’t make it this evening so her place was expertly filled by another pair from Auburn. I’ve talked about CS Unplugged before but it was fascinating to see the experts talking about their experiences and giving us all the experience of what it’s like to be in an Unplugged classroom. I took some photos which will probably capture the immersive and enjoyable sense of this hands-on experience.

Here are some of the double-sided cards that can be used to show the 2D parity trick, where students are drawn into constructing the use and checking of parity with a simple 5×5 (or 9×9) grid of cards. Basically, once drawn up the student can flip any of the cards and the instructor can walk in from outside and legitimately pick the flipped card.

These are Tim’s, from the University of Canterbury, and they are both a handy tool for CS Unplugged and a cool way to give people a calling card of who gave you the talk.

Tim and Lynn were very honest about the degree of knowledge that could be conveyed to elementary school students – we’re not talking about getting all of the CS completely accurate but, in a setting where we can get lost in the cracks, the students would remember that CS people came to their school and it was interesting and engaging. (And, for me, the CS is pretty close. 🙂 )

The next picture is of a Pirate’s Treasure puzzle, where students have to pick A or B and, depending on what they choose, they hop to different islands. This introduces several key computing concepts: Finite State Automata,  Complexity but, for me, it also makes students think about exploring a space in order to be able to improve their decision and thinking processes.

Complexity but, for me, it also makes students think about exploring a space in order to be able to improve their decision and thinking processes.

The next picture is slightly curious and, rather than being an activity, it’s a diagram showing all the states that a VCR could end up in when you’re setting the clock – and the number of different pathways between them. Is it any wonder that these devices give us trouble? Building on what students had learned about the different islands (states) that you could catch a ship to (transition to) – it suddenly explains why human interface design is so incredibly important.

Overall, this was a great workshop. We had many participatory activities – I was the bit representing ‘4’ for a very happy 10 minutes – and an excellent display of robotics and how they could be used with students in camp activities. Also, somewhat counterintuitively, how robots could be used to teach CS Unplugged.

From a theoretical perspective, CS Unplugged is heavily constructivist. In informal terms, constructivists assert that the generation of knowledge and meaning in humans comes from an interaction between what they experience and the frameworks that they have in their head. In this case, CS Unplugged, the basic goal is to present something with which a student can interact, but in its affordance and its goals, it drives them towards forming the correct knowledge of an area of CS, even without us explaining anything. To give an example, the student in the picture had learned quick sort enough to demonstrate it, despite never being explicitly told what quick sort was. She’s 12. The numbers in the pictures show the number of steps for a student using a simple sorting technique, and the one that she used. Yes, she’s shaved over half the steps off.

We had many examples like this – students who learned to count in binary from observation and interaction, without anyone having to formally discuss powers of two or underlying mathematics.

To be honest, I can’t do a three-hour workshop justice in 700 words, and I’d like to get some sleep before tomorrow’s keynote. However, if you haven’t checked out the CS Unplugged website yet, then I strongly recommend it. If you get the chance to see these presenters at work, then I strongly suggest that, too.

Leibhardt: The Game Sensation That’s… not sweeping anywhere (yet!)

Posted: February 27, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: design, education, games, higher education, leibhardt, reflection, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, universal principles of design Leave a commentToday’s post is going to tie together my posts on design and, to illustrate it, I’m going to show you one of the game screens that my Summer Research Scholarship student produced. The game is called Leibhardt and it’s a way of teaching students about adding and removing items to commonly used data structures in Computer Science and programming. Here’s the picture of the playing space, as seen by one of the opponents:

This is still a work in progress but let’s review the production and design process. I set the student a task: to find a way to teach a Computer Science concept using a game. I then gave him a stack of books, a central book as key text, and asked him to go away and come back with some ideas. He then presented a number of good ideas and I selected my prime candidate (which was also his). He then had to present a detailed plan with weekly goals. The project was only six weeks long so we had no time to waste. Over the next few weeks, we developed ideas, refined them and he turned it all into a game, with the assistance of another member of staff who I won’t uniquely identify but, thanks, Claudia!

Let’s look at this in terms of some of the principles I’ve been discussing. We decided to use a game because games are familiar to many people (functional consistency) and the appearance of card games is also something everyone understands (aesthetic consistency). Look at the image. Yes, the cards need some work but it’s got that green baize background we expect and, once the cards are finished, your fingers will naturally be drawn to the cards to select them for playing. I provided a set of nudges to keep the student on the right track, throughout the project, by providing appropriate and directed feedback, as well as controlling the books that he started with and keeping a fairly tight rein on the project until I was sure that he was on the right track. The game itself is full of nudge elements as well to keep the player going – this is a fairly addictive game. I’ve encouraged him to use GUI elements that can only be used in the right way (which is the affordance principle in action), as well as making sure that the system looks the same as every other Java-based game (external consistency). We’re still working on the look and feel of the structures themselves – they need to be consistent with what students have seen before, which is internal consistency in terms of the course context.

Finally, it’s possible for people to easily interrupt and resume games, for me to monitor activity so I can tell if people are undertaking assigned work on playing this game and there also degrees of difficulty involved. This gives us fairly fine-grained control over the performance load of the activity, and greatly reduces the kinematic and cognitive load of playing. Students who are new can choose to, or be expected to, expend less effort to achieve a good result. Expert students can crank up the difficulty and make the task harder. Any student can play it easily, stop playing and then pick it up again later.

I must point out that, while I’ve been heavily involved in the design and mentoring process, what I’ve mostly been doing is guiding a good student and helping him to make good decisions. I’m happy with my contribution but a lot of what I’ve been doing has been helping to organise information for decision making purposes – effectively providing guidance on using the five hat racks.

I hope that this helps you to understand that the design I’m talking about is not choosing Powerpoint templates, although that can be part of it, but is more of a deep-seated commitment to thinking about what we’re doing in order to produce the best work possible. We’re still working on the game and, with any luck we’ll have some versions available for teachers of Data Structures relatively soon.

Fiero! The joy that makes you want to punch the air.

Posted: January 22, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, fiero, games, higher education, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a commentAfter a fun couple of hours writing the previous post, I’ve decided to hunker down and read some more books on data visualisation. However, I wanted to update you on my Summer Research Scholarship student – the one who was developing the game. Well, he demo’d the basic computerised version on Friday and, simply, it works, it’s fun, and he’s got a simple text display going. Next week it’s GUI + networking design and build, then two more weeks of coding and wrapping it up for week 6 with API documentation, extensible framework and a plan for porting it to Android and iPhone.

Let me remind you that he started two weeks ago, was given some books, a brief, and a lot of access to me and my time, as well as my planning skills and overall management. In that time, he has learnt about an entirely new way of presenting information, come up with six ideas, found the best one and chased it with an amazing passion. In two weeks he has a simple working game that could be played right now. The more I work with students, the more I realise that my fears about what they can’t achieve often become constraints on what I allow them to achieve. I (implicitly or explicitly) tell people that This is enough when it sets a false level of achievement for the struggling and it bores the gifted. Yes, there are varying levels of ability and we must educate all of our students, but I’ve seen so many people soar when I’ve given them open skies and a jet pack, that I can spend the time to help those who are still walking, or have fallen once or twice. My belief is that most, if not all, will fly one day. If I don’t believe that, then what am I doing?

It’s the weekend and I’m blogging this because I want you to know how much we can do, as educators, as people, as mentors and, sometimes, as the ones who stand back and let people try. We have to build our world in a way that it’s possible to fly but it’s not fatal to fall.

It’s an enormous challenge and I love it. Fiero is a word that we use for that feeling of achievement and joy that makes you raise your fists into the air and punch out to the sky because you can’t contain how good you feel. My student had such a moment when he worked out one of the core design issues that turned his game from dull to fun. He told me about it, using terminology he’d picked up on this project to describe that joy. Now, I have that feeling because I think that good things are happen. What more can any of us ask for in our jobs, once the mundane issues are settled?

Have a great weekend! Find the joy! Punch the air!

Bang, bang, you’re educated.

Posted: January 14, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: education, games, higher education, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a commentI currently have a summer research scholarship who is working on a project called “Bang Bang, you’re educated: Serious games in Computer Science”. For the last week, he’s been reading a number of books I’ve lent him, reading across a number of key websites and thinking, based on his own experiences, how he could build a game that teaches people interesting things about CS or gives them practice in key skills in CS.

The core book was “Reality is Broken” by Jane McGonigal, who wonders at length why people spend so much time playing games, given how hard it is to get them to perform similar actions in reality. I wouldn’t say I agree with everything that she suggests but as a unifying introductory document, especially with key vocabulary, it’s very valuable. My poor student has a number of other books, of varying age, that he’s using as references to get more depth in key areas. To his credit, not only is he immersed in these books, he reads to and from Uni as well. [ I thought we’d almost managed to stamp out reading? 🙂 ]

He has six weeks work on this project and he started on Monday the 9th. I’d given him some pre-reading, all web-based, before he showed up but on Monday he got all of the books and instructions to read all of “Reality is Broken” while thinking about the project overview and how he could answer some key questions. Tuesday afternoon we met, discussed what he’d done, and then I told him to come up with 5-6 target student groups, approaches, techniques and (ultimately) games. I gave him a giant desk-based flip pad (3M sticky note topped A2 sheets. Very cool), some sticky notes and told him to throw ideas together – then pick the three best for presentation on Thursday.

Thursday he came in and presented three game ideas of which two blew me away and one of which was (only) pretty good. Clear presentation. Good ideas. But, most importantly, he had also selected his favourite (which happened to be mine as well). It was a great moment and, in the spirit of random reward, he walked out with praise and Lindt chocolates. He also left with instructions to turn the prime candidate into a five week development plan, with risk assessment, weekly project goals and extension possibilities. For presentation today.

Today, he presented the candidate, to me and another academic, and the game sounds great. At this stage, it sounds like it will meet the requirements that I set for him at the start. In outline, they were:

- The game must either increase CS knowledge or develop a CS skill.

- It will be sufficiently enjoyable that students will want to play it.

- The game is generally accessible to people at all levels of knowledge and skill.

- Playing the game enhances learning, it doesn’t detract from learning.

- The game may be integrated with external reward activities (as part of an alternate reality game link to a class, for example)

- The game will be ready for students to play in 5 weeks.

The successful candidate is being play tested, with the paper rules, for the first time on Tuesday. Tune in then to see how we went!