We Expect Commitment – That’s Why We Have to Commit As Well.

Posted: May 18, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, beer, BJ's Brewhouse Cupertino, blogging, collaboration, commitment, complaint, compliance, condemnation, curriculum, data visualisation, design, education, educational problem, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, pizza, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a commentI’m currently in Cupertino, California, to talk about how my University (or, to be precise, a Faculty in my University), starting using iPads in First Year by giving them to all starting students. As a result, last night I found myself at a large table on highly committed and passionate people in Education, talking about innovative support mechanisms for students.

Pizza and beer – Fuelling educational discussions since forever. (I love the Internet: I didn’t take any pictures of my food but a quick web-search for BJ’s Pizza Cupertino quickly turned up some good stuff.)

I’ve highlighted committed and passionate because it shows why those people are even at this meeting in the first place – they’re here to talk about something very cool that has been done for students, or a solution that has fixed a persistent or troublesome problem. From my conversations so far, everyone has been fascinated by what everyone else is doing and, in a couple of cases, I was taking notes furiously because it’s all great stuff that I want to do when I get home.

We expect our students to be committed to our courses: showing up, listening, contributing, collaborating, doing the work and getting the knowledge. We all clearly understand that passion makes that easier. Some students may have a sufficiently good view of where they want to go, when they come in, that we can draw on their goal drive to keep them going. However, a lot don’t, and even those who do have that view often turn out to have a slightly warped view of what their goal reality actually is. So, anything we can do to keep a student’s momentum going, while they work out what their goals and passions actually are, and make a true commitment to our courses, is really important.

And that’s where our commitment and passion come into things. As you may know, I travel a lot and, honestly, that’s pretty draining. However, after being awake for 33 hours after a trans-Pacific flight, I was still awake, alert and excited, sitting around last night talking to anyone who would listen with the things that we’re doing which are probably worth sharing. Much more importantly, I was fired up and interested to talk to the people around me who talking about the work that had been put in to make things work for students, the grand visions, the problems that had been overcome and, importantly, they could easily show me what they’d been doing because, in most cases, these systems are highly accessible in a mobile environment. Passion and commitment in my colleagues keeps me going and helps me to pass it on to my students.

Students always know if you’re into what you’re doing. Honestly, they do. Accepting that is one of the first steps to becoming a good teacher because it does away with that obstructive hypocrisy layer that bad teachers tend to cling to. This has to be more than a single teacher outlook though. Modern electronic systems for student support, learning and teaching, require the majority of educators to be involved in your institution. If you say “This is something you should do, please use it” and very few other lecturers do – who do the students believe? Because if they believe you, then your colleagues look bad (whether they should or not, I leave to you). If they believe your colleagues then you are wasting your effort and you’re going to get really frustrated. What about if half the class does and half doesn’t?

We’re going through some major strategic reviews at the moment back home and it’s really important that, whatever our new strategy on electronic support for learning and teaching is, it has to be something that the majority of staff and students can commit to, with results and participation drive or reward their passions. (It’s a good thing we’ve got some time to develop this, because it’s a really big ask!)

The educational times are most definitely a-changin’. (Sorry, I’m in California.) We’ve all seen what happens when new initiatives are pushed through, rather than guided through or introduced with strong support. Some time ago, I ran across a hierarchy of commitment that uses terms that I like, so I’m going to draw from that now. The terms are condemnation, complaint, compliance and commitment.

If we jam stuff through (new systems, new procedures, compulsory participation in on-line activities) without the proper consultation and preparation, we risk high levels of condemnation or under-mining from people who feel threatened or disenfranchised. Even if it’s not this bad, we may end up with people who just complain about it – Why should I? Who’s going to tell me to? Some people are just going to go along with it but, let’s face it, compliance is not the most inspirational mental state. Why are you doing it? Because someone told me to and I just thought I should go along with it.

We want commitment! I know what I’m doing. I agree with what I’m doing. I have chosen to not just take part but to do so willingly and I’m implicitly going to try and improve what’s going on. We want in our students, we want it in our colleagues. To get that in our colleagues for some of the new education systems is going to take a lot of discussion, a lot of thinking, a lot of careful design and some really good implementation, including honest and open review of what works and what doesn’t. It’s also going to take an honest and open discussion of the kind of workload involved to (a) produce everything properly as a set-up cost and (b) the ongoing costs in terms of workload, physical resources and time for staff, organisations and students.

So, if we want commitment from our students, then we must have commitment from our staff, which means that we who are involved in system planning and design have to commit in turn. I’m committed enough to come to California for about 8 more hours than I’m spending on planes here and back again. That, however, means nothing unless I show real commitment and take good things back to my own community, spend time and effort in carefully crafting effective communication for my students and colleagues, and keep on chasing it up and putting the effort in until something good is achieved.

Things I Have Learned From my Cats, About Teaching

Posted: May 17, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, educational problem, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a commentIf you don’t have cats, or don’t like cats, then (a) get cats or (b) give in to your feline masters. More seriously, cats are very handy as a reference for the professional (or enthusiastic amateur) educator, because they ground you before you go and try something that you are heavily invested in with a whole class of students.

The important lessons that you can learn from cats are:

- Cats will only do what you tell them if they were already planning to do it.Obviously, students are more intelligent than cats and can learn a whole range of complex things. However, it’s easy to sometimes think that a particular thing that you did led to a completely different behaviour on the students’ part. Once you’ve removed other factors, isolated the element, repeated the experiment and got the same result? Sure, that’s influential. Before then, it may be any one of the effects that contaminate this kind of perception.

- Cats have good days and bad days. These are randomly allocated.

Sometimes cats stay off the table. Sometimes they don’t. This is for reasons that I don’t understand because I can’t see the whole of the cats’ thinking process – despite them living inside my house for the past 8 years and me being able to observe them the whole time. I’ve realised over the years that I see my students for a very small fraction of their lives and trying to determine when they’re going to be really receptive or not is not easy. I can try to present or set up my course in a way that reaches them most of the time. Sometimes it won’t happen. (I should note that they generally do, however, stay off the tables.) - Cats can’t tell you what’s wrong because they don’t have the vocabulary.Of course, students can talk to me most of the time and we can talk about what’s wrong, but we have very different vocabularies in many ways. By exposing my thoughts and my processes to the students in their language, and scaffolding them to an understanding of the vocabulary of teaching education, or to get them to understand how collaboration isn’t a shorthand for “straight copying”.

This is rather trivial but, as always, it’s about framing and engagement. I suppose I’m saying the things I usually say but with a strange linkage to cat stories. As you read this, I’m probably on a plane somewhere, so I’ll try to be more coherent once I land.

Hurdles and Hang-ups: Identifying Those Things That Trip Up a Student

Posted: May 13, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: curriculum, design, education, educational problem, feedback, Generation Why, higher education, learning, measurement, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches 2 CommentsMost of the courses I teach have a number of guidelines in place that allow a student to, with relative ease and fairly early on, identify if they are meeting the requirements of the course. Some of these are based around their running assessment percentages, where a student knows their mark and can use this to estimate how they’re travelling. We use a minimum performance requirement that says that a student must achieve at least 40% in every component (where a component is “the examination” or “the aggregate mark across the whole of their programming assignments”) and 50% overall in order to pass. If a student doesn’t meet this, but would otherwise pass, we can look at targeted remedial (replacement) assessment in order to address the concern.

Bazinga! (With apologies to the Austrian athlete involved, who suffered no more injury than some cuts to his lower lip and jaw.)

One of the things we use is often referred to as a hurdle assessment, an assessment item that is compulsory and must be passed in order to pass the course. One of the good things about hurdle assessments is that you can take something that you consider to be a crucial skill and require a demonstration of adequate performance in that skill – well before the final examination and, often, in a way that is more practically oriented. Because of this we have practical programming exams early on in our course, to resolve the issues of students who can write about programming but can’t actually program yet.

It would be easy to think of these as barriers to progress, but the term hurdle is far more apt in this case, because if you visualise athletic training for the hurdles, you will see a sequence of hurdles leading to a goal. If you fall at one, then you require more training and then can attempt it again. This is another strong component of our guidelines – if we present hurdles, we must offer opportunities for learning and then reassessment.

Of course, this is the goal, role and burden of the educator: not the cheering on of the naturally gifted, but the encouragement, development and picking up of those who fall occasionally.

Picked correctly, hurdles identify a lack of ability or development in a core skill that is an absolute pre-requisite for further achievement. Picked poorly, it encourages misdirected effort, rote learning or eye-rolling by students as they undertake compulsory make-work.

I spend a lot to time trying to frame what is happening in the course so that my students can keep an eye on their own progress. A lot of what affects a student is nothing to do with academic ability and everything to do with their youth, their problems, their lives and their hang-ups. If I can provide some framing that tells them what is important and when it is important for it to be important, then I hope to provide a set of guides against which students can assess their own abilities and prioritise their efforts in order to achieve success.

Students have enough problems these days, with so many of them working or studying part-time or changing degrees or … well… 21st Century, really, without me adding to it by making the course a black box where no feedback or indicators reach them until I stamp a big red F on their paperwork and tell them to come back next year. If they can still afford it.

Stats, stats and more stats: The Half Life of Fame

Posted: May 5, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: abelson, education, feedback, half-life of fame, higher education, Korzybski, learning, measurement, MIKE, reflection 4 CommentsSo, here are the stats for my blog, at time of writing. You can see a steady increase in hits over the last few weeks. What does this mean? Have I somehow hit a sweet spot in my L&T discussions? Has my secret advertising campaign paid off (no, not seriously). Well, there are a couple of things in there that are both informative… and humbling.

Firstly, two of the most popular searches that find my blog are “London 2012 tube” and “alone in a crowd”. These hits have probably accounted for about 16% of my traffic for the past three weeks. What does that tell me? Well, firstly, the Olympics aren’t too far away and people are looking for how convenient their hotels are. The second is a bit sadder.

The second search “alone in a crowd” is coming in across two languages – English and Russian. I have picked up a reasonable presence in Russia and Ukraine, mostly from that search term. It seems to contribute a lot to my (Australian) Monday morning feed, which means that a lot of people seem to search for this on Sundays.

But let me show you another graph, and talk about the half life of fame:

That’s since the beginning my blogging activities. That spike at Week 9? That’s when I started blogging SIGCSE and also includes the day when over 100 people jumped on my blog because of a referral from Mark Guzdial. That was also the conference at which Hal Abelson referred to a concept of the Half Life of fame – the inevitable drop away after succeeding at something, if you don’t contribute more. And you can see that pretty clearly in the data. After SIGCSE, I was happily on my way back to being read by about 20-30 people a day, tops, most of whom I knew, because I wasn’t providing much more information to the people who scanned me at SIGCSE.

Without consciously doing it, I’ve managed to put out some articles that appear to have wider appeal and that are now showing up elsewhere. But these stats, showing improvement, are meaningless unless I really know what people are looking at. So, right now I’m pulling apart all of my log data to see what people are actually reading – whether I have an increasing L&T presence and readership, or a lot of sad Russian speakers or lost people on the London Underground system. I’m expecting to see another fall-away very soon now and drop down to the comfortable zone of my little corner of the Internet. I’m not interested in widespread distribution – I’m interesting in getting an inspiring or helpful message to the people who need it. Only one person needs to read this blog for it to be useful. It just has to the right one person. 🙂

One of the most interesting things about doing this, every day, is that you start wondering about whether your effort is worth it. Are people seeking it out? Are people taking the time to read it or just clicking through? Are there a growing number of frustrated Tube travellers thinking “To heck with Korzybski!” Time to go into the data and look. I’m going to keep writing regardless but I’d like to get an idea of where all of this is going.

Identity and Community – Addressing the ICT Education Community

Posted: April 27, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, ALTA, education, feedback, higher education, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a commentHad a great meeting at Swinburne University, (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia), today as part of my ALTA Fellowship role. I brought the talk and early outcomes from the ALTA Forum in Queensland into (sunny-ish?) Melbourne and shared it with a new group of participants.

I haven’t had time to write my notes up yet but the overall sentiment was pretty close to what was expressed at the ALTA Forum initially:

- We don’t have an “ICT is…” identity that we can point to. Dentists do teeth. Doctors heal the sick. Lawyers do law. ICT does… what?

- We need a common dissemination point for IT, CS, IS, ICT, CS-EE… etc. rather than the piecemeal framework we currently have that is strongly aligned with subdivision of the discipline.

- We need professionalism in learning and teaching, where people dedicate time to improve their L&T – no more stagnant courses!

- We need to have enough time to be professional! L&T must be seen as valuable and be allocated enough time to be undertaken properly.

- It would be great to have a Field of Research Code for Education within the Discipline of ICT – as distinct from general education coding – to make sure that CS Ed/ICT Ed is seen as educational research in the discipline, rather than a non-specific investigation.

- We need to identify and foster a community of practice to get out of the silos. Let’s all agree that we want to do this properly and ignore school and University boundaries.

- We need to stop talking about the lack of national community and start addressing the lack of a national community.

So a good validation for the early work at the Forum and I’m really looking forward to my meeting at RMIT tomorrow. Thanks, Graham and Catherine, for being so keen to host the first official ALTA engagement and dissemination event!

Why Do Students Plagiarise?

Posted: April 20, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, educational problem, feedback, higher education, plagiarism, teaching, teaching approaches, turnitin 2 CommentsFor those who don’t know, Turnitin is automated plagiarism detection software that scans submitted documents and looks to see if there are matches to text found inside its databases. And, it should be noted, Turnitin’s databases are large. It’s a great tool, although it can be pricey to access, because you use it as a verification and detection tool, the obvious use, and as a teaching tool, where students submit their own work to see how much cut-and-paste and unattributed work they have included. Taking the latter approach allows students to improve their work and then you can get them to submit their work AND their Turnitin report for the final submission. This makes the student an active participant in their own development – a very good thing.

I’m on the Turnitin mailing list so I receive regular updates and the one that came through today had a really nice graphic that I’m going to share here today, although I note that it is associated with the Turnitin webcast “Why Students Plagiarize?” by Jason Stephens. Here, he summarises the three common motivational factors.

I love this diagram. It gets to the core of the problem and, unsurprisingly as I’ve linked it here, completely agrees with my thinking and experience on this. Let’s go through these points. (I haven’t watched the talk, I just liked the graphic. I’m planning to watch the talk next week and I hope to have something to share here from that.)

- Under-interested

If a student isn’t engaged, they won’t take the work seriously and they won’t really care about allocating enough time to do it – or to do it properly. Worse, if the assignment is seen (fairly or not) as make work or if the educator is seen to be under-interested, then the lack of value associated with the assignment may allow some students to rationalise a decision to grab someone else’s work, put a quick gloss on it and then hand it up. No interest, no engagement, no pride – no worth. Students have to be shown that the work is valuable and that we are interested – which means that we have to be interested and the work has to be worthwhile doing! - Under Pressure

Students tend to allocate their effort based on proximity of deadlines. Wait, let me correct that. People tend to allocate their effort based on proximity of deadlines. Given that students are not yet mature in many of their professional skills, their ability to estimate how long a task will take is also not guaranteed to be mature. As a result, many of our students are under a cascade of time pressures. This is never a justification for plagiarism but it is often the foundation of a rationalisation for plagiarism. “I’m in a hurry and I really need to get this done so I’ll take shortcuts.” Training students to improve their time management and encouragement to start and submit work early are the best ways to help fight this, in conjunction with plagiarism awareness. - Unable

Students who don’t have the skills can’t do the work themselves. To complete assignments without having the understanding yourself, you have to use the work of other people. For us, this means that we have to quickly identify when students don’t have the knowledge to proceed and try to remedy it, while still maintaining out academic standards and keeping our pass bars form and at the right level. Sometimes this is just a perception, rather than the truth, and guidance and encouragement can help. Sometimes we need remedial work, pre-testing and hurdles to make sure that students are at the right level to proceed. It’s a complex juggling act that forms the basis of what we do – catering to everyone across the range of abilities.

The main reason that I like this diagram so much is that it doesn’t say anything about where the student comes from, or who they are, it talks about the characteristics that are common to most students who plagiarise. Let’s give up the demonisation and work on the problems.

The Community Lessons of In-Flight Entertainment

Posted: April 15, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: community, community building, education, feedback, higher education, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches 2 CommentsNow, this post isn’t just a reason to reuse that picture of the world’s most worrying looking pilot.

It carries on from the discussion of blended learning that I started yesterday. These days we tend to mix face-to-face, on-line and mobile learning methods in order to deal with the varied nature of students who take part in our classes. It’s partly driven by accessibility, by geography, by the market and lots of other factor. My question yesterday was ‘What will the classroom look like in 2020?’ – my concern today is what will happen to our student communities if we don’t properly manage the transition to 2020.

Let me take you back to when I was much younger, flying from the UK to Australia on a 747. Back then, planes had smoking and non-smoking sections (with no real divider, apparently the smoke just knew), and the in-flight entertainment was some dodgy music channels on stethoscope-like headphones and one (or two) films played on big screens at low resolution. This was the norm for long haul (except for the smoking) up until the mid-late 90s. (Except for Business Class, I’m told, where the advances came in much earlier)

What did this heavily synchronised central resource focus mean to the planes and their passengers?

- Individual requirements were ignored

If you needed to get up to go the bathroom, you missed part of the film. If the stewards asked you a question, you missed part of the film. If you fell asleep, you missed part of the film. The film was never replayed. Worse, films on planes were shown well in advance of their release into Australia (still happens occasionally) so it would be potentially months until you could see the rest of the film. Interestingly, and I remember this because I was very young, they showed films that would appeal to the majority of their paying passengers – grown-ups. One I remember was “The Drowning Pool”, rated PG, being shown. Violence, some blood, intense scenes and some swearing. Or so I found out after the fact because (a) I was 7 and couldn’t see over the seats and (b) I fell asleep. But you can probably imagine that a number of parents would have preferred that children not be exposed to a long and rather dull movie that nearly kills Paul Newman with a fairly intense drowning scene. (Sorry, spoilers, but it’s from 1975. And not very good. Watch Harper instead, the original movie about the character.) - It created an artificial scarcity

There are never enough bathrooms on a plane. Force people to sit down for 2 hours to watch a movie where they can’t pause it, stop watching or do anything else and you’ll cause a rush for the bathrooms at the end of the film. - People were still part of the plane ‘community’

If turbulence happened, as it does, or the pilot needed to make any other announcement, the fact that we were all wired into the same dissemination mechanisms meant that we could all still be reached. There was only one game in town, such as it was, and you were watching it, reading to ignore it (in which case the intercom would reach you) or asleep (but still reachable if the intercom pings are loud enough.)

Of course, this meant that a lot of people weren’t happy but they were all in one contactable community. Lots of conversation happened before the movies, while people queued in those big groups, and, depending on when the movie stopped, after the movie. Ideal? No. Frustrating? Yes, occasionally. Isolating? No, not really.

Then, of course, we moved to individual screens in the backs of seats (for most long haul carriers across the European Singapore to UK run and the trans-Pacific run) and, initially, this allowed you choice of title, but all synchronised to a repeating loop. Now you could have some control and, if you missed something for any reason, if you waited a couple of hours you could see it again. So point 1 was a little better. Point 2 still held because the end of movie times still ran into each other and bathroom queues were huge. We were, however, all hooked into the one entertainment system and still part of the plane community.

Next we got true video on demand – you could watch what you wanted, when you wanted (even from the moment you sat in your seat until the plane pulled up, recently). Now point 1 is dealt with. You can pause films, lock out the bad channels for your kids, rewind, flick, change your mind – and the queues for the toilets are way, way down. Point 2 is dealt with. What’s weird here is the change in community. Back when movies were synchronised, stewards would know roughly where everyone was in their movies and could, if they wanted to, work around it. With movies being personalised, any contact from a steward may force you to interrupt your activity – minor point, not too bad, but a change in the role of the steward. You are, however, still on the main information distribution mechanism, which is the intercom. I can still be reached.

You know where I’m going, I imagine. Last night I jumped on a plane that was only a 2.5 hour flight. Sometimes they have seat-back VOD, and I watched Tom Cruise on the way over on that system, and sometimes they don’t. I packed my iPad with lots of legally downloaded BBC goodies and, when I discovered that the plane only had an old AV system, I watched Dr Who episodes all the way home. Isolated. So disconnected from the plane community that a steward had to tap me on the shoulder to let me know that the announcement had gone through to tell me to switch off the iPad as I hadn’t heard it.

Right now I can completely meet my own individual requirements, without using the plane’s, and because so many other people around me were doing the same thing, we never got the synchronisation going to the point that we created artificial scarcity. Only one problem – we were completely divorced from the ‘official’ distribution systems of the plane, such as the intercom announcements, seat belt signs (why look up?) and dings. Sufficiently immersed in my personalised viewing that aircraft attitude changes, which I usually notice, passed me by.

As we develop the electronic communities of the future we have to remember that while allowing customisation and adaptation to individual needs is usually highly desirable, and that artificial restrictions, choke points and other points of failure are highly undesirable, that we have to juggle these with the requirement to be able to create a community. Lots of good research shows the value of a strong student community but, without the ability to oversee, suggest, guide and mentor that community, we end up with a separate community that may take directions that are not the ones that they should. Our challenge, as we work towards the classroom of 2020, is to work out which kinds of communities we want to build and how we construct systems around these that keep all the good things we want, while keeping educators and students connected.

Putting the pieces together: Constructive Feedback

Posted: April 6, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: card shouting, design, education, feedback, higher education, teaching, teaching approaches, tools Leave a commentOver the last couple of days, I’ve introduced a scenario that examines the commonly held belief that negative reinforcement can have more benefit than positive reinforcement. I’ve then shown you, via card tricks, why the way that you construct your experiment (or the way that you think about your world) means that this becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

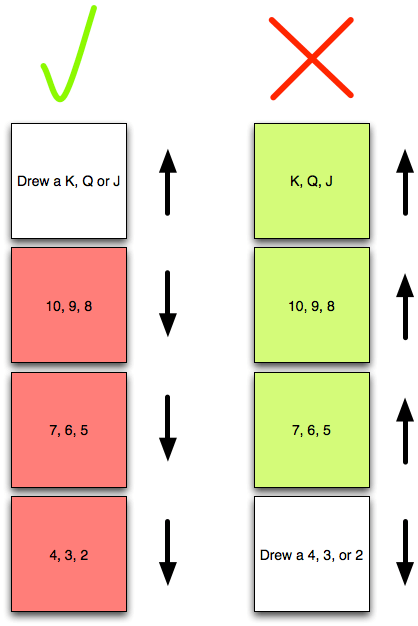

Now let’s talk about making use of this. Remember this diagram?

This shows what happens if, when you occupy a defined good or bad state, you then redefine your world so that you lose all notion of degree and construct a false dichotomy through partitioning. We have to think about the fundamental question here – what do we actually want to achieve when we categorise activities as good or bad?

Realistically, most highly praiseworthy events are unusual – the A+. Similarly, the F should be less represented across our students than the P and the “I’ve done nothing, I don’t care, give me 0” should be as unlikely as the A+. But, instead of looking at outcomes (marks), let’s look at behaviours. Now I’m going to construct my feedback to students to address the behaviour or approach that they employed to achieve a certain outcome. This allows me to separate the B+ of a gifted student who didn’t really try from the B+ of a student who struggled and strived to achieve it. It also allows me to separate the F of someone who didn’t show up to class from the F of someone who didn’t understand the material because their study habits aren’t working. Finally, this allows me to separate the A+ of achievement from the A+ of plagiarism or cheating.

Under stress, I expect people to drop back down in their ability to reason and carry out higher-level thought. We could refer to Maslow or read any book on history. We could invoke Hick’s Law – that time taken to make decisions increases as function of the number of choices, and factor in pilot thresholds, decision making fatigue and all of that. Or we could remember what it was like to be undergraduates. 🙂

Let me break down student behaviours into unacceptable, acceptable and desirable behaviours, and allocate the same nomenclature that I did for cards. So the unacceptable are now the 2,3,4, the acceptable and 5-10, and the desirable are J-K. (The numbers don’t matter, I’m after the concept.) When I construct feedback for my students, I want to encourage certain behaviours and discourage others. Ideally, I want to even develop more of certain behaviours (putting more Kings in the deck, effectively). But what happens if I don’t discourage the unacceptable behaviours?

Under stress, under reduced cognitive function and reduced ability to make decisions, those higher level desirable behaviours are most likely going to suffer. Let us model the student under stress as a stacked deck, where the Q and K have been removed. Not only do we have less possibility for praise but we have an increased probability of the student making the wrong decision and using a 2,3,4 behaviour. It doesn’t matter that we’ve developed all of these great new behaviours (added Kings), if under stress they all get thrown out anyway.

So we also have to look at removing or reducing the likelihood of the unacceptable behaviours. A student who has no unacceptable behaviour left in their deck will, regardless of the pressure, always behave in an acceptable manner. If you can also add desirable behaviours then they have an increase chance of doing well. This is where targeted feedback comes in at the behavioural level. I don’t need to worry about acceptable behaviours and I should be very careful in my feedback to recognise that there is an asymmetric situation where any improvement from unacceptable is great but a decline from desirable to acceptable may be nowhere near as catastrophic. Moderation, thought and student knowledge are all very useful concepts here. But we can also involve the student in useful and scaleable ways.

Raising student awareness of how their own process works is important. We use reflective exercises midway through our end-of-first year programming course to develop student process awareness: what worked, what didn’t work, how can you improve. This gives students a framework for self-assessment that allows them to find their own 2s and their own Kings. By getting the students to do it, with feedback from us, they develop it in their own vocabulary and it makes it ideal for sharing with other students at a similar level. In fact, as the final exercise, we ask students to summarise their growth in their process awareness during the course and ask them for advice that they would give to other students about to start. Here are three examples:

Write code. Go beyond your practicals, explore the language, try things out for yourself. The more you code, the better you’ll get, so take every opportunity you can.

If I could give advice to a future … student, I would tell them to test their code as often as possible, while writing it. Make sure that each stage of your code is flawless before going onto the next stage.

If I could give one piece of advice to students …, it would be to start the coding early and to keep at it. Sometimes you can have a problem that you just can’t work out how to fix but if you start early you leave yourself time to be able to walk away and come back later. A lot of the time when you come back you will see the problem very quickly and wonder why you couldn’t see it before.

There are a lot of Kings in the above advice – in fact, let’s promote them and call them Aces, because these are behaviours that, with practice, will become habits and they’ll give you a K at the same time as removing a 2. “Practise your coding skills” “Test your code thoroughly” “Start early” Students also framed their lessons in terms of what not to do. As one student reflected, he knew that it would take him four days to write the code, so he was wondering why he only started two days out – you could read the puzzlement in the words as he wrote them. He’d identified the problem and, by semester’s end, had removed that 2.

I’m not saying anything amazing or controversial here, but I hope that this has framed a common situation in a way that is useful to you. And you got to shout at cards, too. Bonus!

Card Shouting: Teaching Probability and Useful Feedback Techniques by… Yelling at Cards

Posted: April 5, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: card shouting, education, feedback, fiero, games, higher education, resources, teaching, teaching approaches, tools 2 CommentsI introduced a teaching tool I call ‘Card Shouting’ into some of my lectures a while ago – usually those dealing with Puzzle Based Learning or thinking techniques. What does Card Shouting do? It demonstrates probability, shows why experimental construction is important and engages your class for the rest of the lecture. So what is Card Shouting?

(As a note, I’ve been a bit rushed today and I may not have put this the best way that I could. I apologise for that in advance and look forward to constructive suggestions for clarity.)

Take a standard deck of cards, shuffle it and put it face down somewhere where the class can see it. (You either need very big cards or a document camera so that everyone can see this in a large class. In a small class a standard deck is fine.)

Then explain the rules, with a little patter. Here’s an example of what I say: “I’m sick and tired of losing at Poker! I’ve decided that I want to train a pack of cards to give me the cards I want. Which ones do I want? High cards, lots of them! What don’t I want? Low cards – I don’t want any really low cards.”

Pause to leaf through the deck and pull out a Ace, King and Queen. Also grab a 2,3 and 4. Any suit is fine. Hold up the Ace, King and Queen.

“Ok, these guys are my favourites. What I’m going to do, after this, is shuffle everything back in and draw a card from the top of the deck and flip it up so you can see it. If it’s one of these (A, K, Q), I want to hear positive things – I want ‘yeahs!’ and applause and good stuff. But if it’s one of these (hold up 2,3 and 4) I want boos and hisses and something negative. If it’s not either – well, we don’t do anything.” (Big tip: put a list of the accepted positive and negative phrases on the board. It’s much easier that having to lecture people on not swearing)

“Let’s find out what works best: praise or yelling- but we’re going to have measure our outcomes. I want to know if my training is working! If I draw a bad card and abuse it, I want to see improvement – I don’t want to see one of the bad cards on the next draw. If I draw a good card, and praise it, I want the deck to give me another good card – if it’s lower than a J, I’ve wasted my praise!” Then work through with the class how you can measure positive and negative reaction from the cards – we’ve already set up the basis for this in yesterday’s post, so here’s that diagram again.

In this case, we record a tick in the top left hand box if we get a good card and, after praising it, we get another good card. We put a tick in top right hand box if we draw a bad card, abuse the deck, and then get anything that is NOT a bad card. Similarly for the bottom row, if we praise it and the next card is not good, we put a mark in the bottom left hand box and, finally, if we abuse the card and the next card is still bad, we record a mark in the bottom right hand box.

Now you shuffle and start drawing cards, getting the reactions and then, based on the card after the reaction, record improvement or decline in the face of praise and abuse. If you draw something that’s neither good NOR bad to start with – you can ignore it. We only care about the situation when we have drawn a good or a bad card and what the immediate next card is.

The pattern should emerge relatively quickly. Your card shouting is working! If you get a card in the bad zone, you shout at it, and it’s 3 times as likely to improve. But wait, praise doesn’t do anything for these cards! You can praise a card and, again, roughly 3 times as often – it gets worse and drops out of the praise zone!

Not only have we trained the deck, we’ve shown that abuse is a far more powerful training tool!

Wait.

What? Why is this working? I discussed this in outline yesterday when I pointed out it’s a commonly held belief that negative reinforcement is more likely to cause beneficial outcome based on observation – but I didn’t say why.

Well, let’s think about the problem. First of all, to make the maths easy, I’m going to pull the Ace out of the deck. Sorry, Ace. Now I have 12 cards, 2 to K.

Let me redefine my good cards as J, Q, K. I’ve already defined my bad cards as 2, 3, 4. There are 12 different card values overall. Let me make the problem even simpler. If we encounter a good card, and praise it, what are the chances that I get another good card? (Let’s assume that we have put together a million shuffled decks, so the removal of one card doesn’t alter the probabilities much.)

Well, there are 3 good card values, out of 12, and 9 card values that aren’t good – so that’s 9/12 (75%) chance that I will get a not good card after a good card. What about if I only have 12 cards? Well, if I draw a K, I now only have the Q and the J left in my good card set, compared to 9 other cards. So I have a 9/11 chance of getting a worse card! 75% chance of the next card being worse is actually the best situation.

You can probably see where this is going. I have a similar chance of showing improvement after I’ve abused the deck for giving me a bad card.

Shouting at the cards had no effect on the situation at all – success and failure are defined so that the chances of them occurring serially (success following success, failure following failure) are unlikely but, more subtly, we extend the definition of bad when we have a good card – and vice versa! If we draw any card from 5 to 10 normally, we don’t care about it, but if we want to stay in the good zone, then these 6 cards get added to the bad cards temporarily – we have effectively redefined our standards and made it harder to get the good result. Here’s a diagram, with colour for emphasis, to show the usually neutral outcomes are grouped with the extreme.. No wonder we get the results we do! The rules that we use have determined what our outcome MUST look like.

So, that’s Card Shouting. It seems a bit silly but it allows you to start talking about measurement and illustrate that the way you define things is important. It introduces probability in terms of counting. (You can also ask lots of other questions like “What would happen if good was 8-K and bad was 2-7?”)

My final post on this, tomorrow, is going to tie this all together to talk about giving students feedback, and why we have to move beyond simple definitions of positive and negative, to focus on adding constructive behaviours and reducing destructive behaviours. We’re going to talk about adding some Kings and removing some deuces. See you then.

It’s Feedback Week! Yelling at Pilots is Good for Them!

Posted: April 4, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: card shouting, design, education, feedback, higher education, measurement, pilot training, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches 1 CommentThe next few posts will deal with effective feedback and the impact of positive and negative reinforcement. I’ll start off with a story that I often tell in lectures.

There’s a well established fact among pilot instructors, in the Air Force, that negative reinforcement works better than positive reinforcement. Combat pilots are very highly trained, go through an extremely rigorous selection procedure and have to maintain a very high level of personal discipline and fitness. The difference between success and failure, life and death effectively, can come down to one decision. During training, these pilots are put under constant stress, to try and prepare them for the real situation.

The instructors have observed that these pilots respond better to being yelled at than being congratulated. What’s their evidence? Well, if a pilot does something really well, and is praised, chances are his or her performance will get worse. Whereas, if the pilot does something bad, or dangerous, and you yell at him or her, his or her performance will improve. Well, that’s a pretty simple framework. Let’s draw it as a diagram.

Now, of course, to see the impact of praise or abuse, you have to record what you did (the praise or abuse) and then what happened (improvement or decline). So we need to draw up some boxes. Ticks mean praise, crosses mean abuse. Up arrow mean improvement, down arrow means decline. A tick in the box that you reach by selecting the column that belongs to Praise (tick) and the row that belongs to Improvement (up arrow) means that the pilot improved after praise. Let’s look at a picture.

So here we can see that, much as an instructor would expect, when I’m nice to you, you get worse more often that you get better. You get better once when praised, compared to getting worse three times. But, wow, when I yelled at you, you get better far more often than you got worse!

There is, of course, a trick here. Yes, it appears that shouting works better than praising but, without giving the game away in the comments (or Googling), do you know why? (The data is a reasonable approximation of the real situation, so there are no hidden arrows or ticks anywhere. 🙂 )

Now, true confession, the picture above is not actually of pilot training – I don’t have an F18 on my desk – but it will be a reasonable approximation of the situation, although it comes from a different source. The graph above comes from a game called “Card Shouting” and I’ll tell you more about that in tomorrow’s post.