Talk to the duck!

Posted: August 17, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, grand challenge, higher education, principles of design, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, time banking, work/life balance, workload Leave a commentI’ve had a funny day. Some confirmed acceptances for journals and an e-mail from a colleague regarding a collaboration that has stalled. When I set out to readjust my schedule to meet a sustainable pattern, I had a careful look at everything I needed to do but I overlooked one important thing: it’s easier to give the illusion of progress than it is to do certain things. For example, I can send you a ‘working on it’ e-mail every week or so and that takes me about a minute. Actually doing something could take 4-8 hours and that’s a very large amount of time!

So, today was a hard lesson because I’ve managed to keep almost all of the balls in the air, juggling furiously, as I trim down my load but this one hurts. Right now, someone probably thinks that I don’t care about their project – which isn’t true but it fell into the tough category of important things that needs a lot of work to get to the next stage. I’ve sent an apologetic and embarrassed e-mail to try and get this going again – with a high prioritisation of the actual work – but it’s probably too late.

The project in question went to a strange place – I was so concerned about letting the colleague down that I froze up every time I tried to do the work. Weird but true and, ultimately, harmful. But, ultimately, I didn’t do what I said I’d do and I’m not happy.

So how can I turn this difficult and unpleasant situation into something that I can learn from? Something that my students can benefit from?

Well, I can remember that my students, even though they come in at the start of the semester, often come in with overheads and burdens. Even if it’s not explicit course load, it’s things like their jobs, their family commitments, their financial burdens and their relationships. Sometimes it’s our fault because we don’t correctly and clearly specify prerequisites, assumed knowledge and other expectations – which imposes a learning burden on the student to go off and develop their own knowledge on their own time.

Whatever it is, this adds a new dimension to any discussion of time management from a student perspective: the clear identification of everything that has to be dealt with as well as their coursework. I’ve often noticed that, when you get students talking about things, that halfway through the conversation it’s quite likely that their eyes will light up as they realise their own problem while explaining things to other people.

There’s a practice in software engineering that is often referred to as “rubber ducking”. You put a rubber duck on a shelf and, when people are stuck on a problem, they go and talk to the duck and explain their problem. It’s amazing how often that this works – but it has to be encouraged and supported to work. There must be no shame in talking to the duck! (Bet you never thought that I’d say that!)

I’m still unhappy about the developments of today but, for the purposes of self-regulation and the development of mature time management, I’ve now identified a new phase of goal setting that makes sense in relation to students. The first step is to work out what you have to do before you do anything else, and this will help you to work out when you need to move your timelines backwards and forwards to accommodate your life.

This may actually be one of the best reasons for trying to manage your time better – because talking about what you have to do before you do any other assignments might just make you realise that you are going to struggle without some serious focus on your time.

Or, of course, it may not. But we can try. We can try with personal discussions, group discussions, collaborative goal setting – students sitting around saying “Oh yeah, I have that problem too! It’s going to take me two weeks to deal with that.” Maybe no-one will say anything.

We can but try! (And, if all else fails, I can give everyone a duck to talk to. 🙂 )

Group feedback, fast feedback, good feedback

Posted: August 16, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: authenticity, collaboration, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, grand challenge, in the student's head, plagiarism, principles of design, reflection, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, vygotsky Leave a commentWe had the “first cut” poster presentation today in my new course. Having had the students present their pitches the previous week, this week was the time to show the first layout – put up your poster and let it speak for itself.

The results were, not all that surprisingly, very, very good. Everyone had something to show, a data story to tell and some images and graphs that told the story. What was most beneficial though was the open feedback environment, where everyone learned something from the comments on their presentation. One of my students, who had barely slept for days and was highly stressed, got some really useful advice that has given him a great way forward – and the ability to go to bed tonight with the knowledge that he has a good path forward for the next two weeks.

Working as a group, we could agree as a group, discuss and disagree, suggest, counter-suggest, develop and enhance. My role in all of this is partially as a ‘semi-expert’ but also as a facilitator. Keep the whole thing moving, keep it to time, make sure that everyone gets a good opportunity to show their work and give and receive feedback.

The students all write down their key feedback, which is scanned as a whole and put on the website so that any good points that went to anyone can now be used by anyone in the group. The feedback is timely, personal and relevant. Everyone feels that these sessions are useful and the work produced reflects the advantages. But everyone talks to everyone else – it’s compulsory. Come to the session, listen and then share your thoughts.

This, of course, reveals one of my key design approaches: collaboration is ok and there is no competitiveness. Read anything about the grand challenges and you keep seeing the word ‘community’ through it. Solid and open communities, where real and effective sharing happens, aren’t formed in highly competitive spaces. Because the students have unique projects, they can share ideas, references and even analysis techniques without plagiarism worries – because they can attribute without the risk of copying. Because there is no curve grading, helping someone else isn’t holding you back.

Because of this, we have already had two informal workshop groups form to address issues of analysis and software, where knowledge passes from person to person. Before today’s first cut presentation, a group was sitting outside, making suggestions and helping each other out – to achieve some excellent first cut results.

Yes, it’s a small group so, being me, now I’m worrying about how I would scale this up, how I would take this out to a large first-year class, how I would get it to a school group. This groups need careful facilitation and the benefit of inter-group communication is derived from everyone in the group having a voice. The number of interactions scale with the square of the group size, so there’s a finite limit to how many people I can have in the group and fit it into a two-hour practical session. If I split a larger class into sub-groups, I lose the advantage of everyone see in everyone else’s work.

But this can be solved, potentially with modern “e-” techniques, or a different approach to preparation, although I can’t quite see it yet. There’s a part of me that thinks “Ask these students how they would approach it”, because they have viewpoints and experience in this which complements mine.

Every week that goes by, I wonder if we will keep improving, and keep rewarding the (to be honest) risk that we’re taking in running a small course like this in leaner times. And, every week, the answer is a resounding “yes”!

Here’s to next week!

Putting it all together – discussing curriculum with students

Posted: August 15, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, collaboration, community, curriculum, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, popeye, principles of design, reflection, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, tools, wimpy, workload Leave a commentOne of the nice things about my new grand challenges course is that the lecture slots are a pre-reading based discussion of the grand challenges in my discipline (Computer Science), based on the National Science Foundation’s Taskforce report. Talking through this with students allows us to identify the strengths of the document and, perhaps more interestingly, some of its shortfalls. For example, there is much discussion on inter-disciplinary and international collaboration as being vital, followed by statements along the lines of “We must regain the ascendancy in the discipline that we invented!” because the NSF is, first and foremost, a US-funded organisation. There’s talk about providing the funds for sustainability and then identifying the NSF as the organisation giving the money, and hence calling the shots.

The areas of challenge are clearly laid out, as are the often conflicting issues surrounding the administration of these kinds of initiative. Too often, we see people talking about some amazing international initiative – only to see it fail because nobody wants to go first, or no country/government wants to put money up that other people can draw on until everyone does it at the same time.

In essence, this is a timing and trust problem. If we may quote Wimpy from the Popeye cartoons:

The NSF document lays bare the problem we always have: those who have the hamburgers are happy to talk about sharing the meal but there are bills to be paid. The person who owns the hamburger stand is going to have words with you if you give everything away with nothing to show in return except a promise of payment on Tuesday.

Having covered what the NSF considered important in terms of preparing us for the heavily computerised and computational future, my students finished with a discussion of educational issues and virtual organisations. The educational issues were extremely interesting because, having looked at the NSF Taskforce report, we then looked at the ACM/IEEE 2013 Computer Science Strawman curriculum to see how many areas overlapped with the task force report. Then we looked at the current curriculum of our school, which is undergoing review at the moment but was last updated for the 2008 ACM/IEEE Curriculum.

What was pleasing was, rom the range of students, how many of the areas were being addressed throughout our course and how much overlap there was between the highlighted areas of the NSF Report and the Strawman. However, one of the key issues from the task force report was the notion of greater depth and breadth – an incredible challenge in the time-constrained curriculum implementations of the 21st century. Adding a new Knowledge Area (KA) to the Strawman of ‘Platform Dependant Computing’ reflects the rise of the embedded and mobile device yet, as the Strawman authors immediately admit, we start to make it harder and harder to fit everything into one course. Combine this with the NSF requirement for greater breadth, including scientific and mathematical aspects that have traditionally been outside of Computing, and their parallel requirement for the development of depth… and it’s not easy.

The lecture slot where we discussed this had no specific outcomes associated with it – it was a place to discuss the issues arising but also to explain to the students why their curriculum looks the way that it does. Yes, we’d love to bring in Aspect X but where does it fit? My GC students were looking at the Ethics aspects of the Strawman and wondered if we could fit Ethics into its own 3-unit course. (I suspect that’s at least partially my influence although I certainly didn’t suggest anything along these lines.) “That’s fine,” I said, “But what do we lose?”

In my discussions with these students, they’ve identified one of the core reasons that we changed teaching languages, but I’ve also been able to talk to them about how we think as we construct courses – they’ve also started to see the many drivers that we consider, which I believe helps them in working out how to give feedback that is the most useful form for us to turn their needs and wants into improvements or developments in the course. I don’t expect the students to understand the details and practice of pedagogy but, unless I given them a good framework, it’s going to be hard for them to communicate with me in a way that leads most directly to an improved result for both of us.

I’ve really enjoyed this process of discussion and it’s been highly rewarding, again I hope for both sides of the group, to be able to discuss things without the usual level of reactive and (often) selfish thinking that characterises these exchanges. I hope this means that we’re on the right track for this course and this program.

The Key Difference (or so it appears): Do You Love Teaching?

Posted: August 12, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, blogging, collaboration, community, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, higher education, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, workload 3 CommentsI wander around fair bit for work. (I make it sound more impressive than that but the truth is that I end up in lots of different places to work on my many projects and sometimes the movement, although purposeful, is more Brownian than not – due to life.) I’ve had a chance to talk to a lot of people who teach – some of whom are putting vast amounts of effort into it and some of whom aren’t.

The key difference, unsurprisingly, is generally the passion behind it. We see this in our students. They will spend days working on a Minecraft construction to simulate an Arithmetic and Logic Unit, but won’t always put in the two hours to write 20 lines of C++ code. They will write 20,000 words on their blog but can’t give you a 1,000 word summary.

We put effort into the things that we are interested in. Sure, if we’re really responsible and have self-regulation nailed, then we can do things that we’re not interested in, or actively dislike, but it’s never really going to have the same level of effort or commitment.

Passion (or the love of something) is crucial. Some days I have so much to say on the blog that I end up with 4-5 days stocked up in the queue. Some days I struggle to come up with the daily post or, as yesterday, I just run out of time to hit the 4am post cycle because I am doing other things that I am passionate about. Today, of course, the actual deadline timer is running and it seems to have made me think – now I’m passionate and now you’ll get something worth reading. If I’d stayed up until after my guests had left last night, written just anything to meet the deadline? It wouldn’t be anywhere near my best work.

Passion is crucial.

Which brings me to teaching. I know a lot of academics – some who are research/teaching/admin, some research only, some teaching/admin and… well, you get the picture. The majority are the ‘3-in-1’ academics and, in many regards, looking at their student evaluations and performance metrics will not tell you anything about them as a teacher that you can’t learn by sitting down with them and talking about their teaching. It is hard to shut me up about my courses and my students, the things I’m trying, the things I’m thinking of adopting, the other areas I’m looking at, the impact of what other Unis and people are doing, the impact of reports. I am a (junior) scholar in the discipline of learning and teaching and I really, really love teaching. For me, putting effort into it is inevitable, to a great extent.

Then I talk to colleagues who really just want to do their research and be left alone. Everything else is a drag on their research. Administration will get the minimum effort, if it’s done. Teaching is something that you have to do and, if the students don’t get it, then it’s their fault. What is so weird about this is that these people are, in the vast majority, excellent scholars in their own discipline. They research and read heavily, they are aware of what every other researcher is doing in this area, they know if their work has a chance for publication or grants. Having these skills, they then divide the world into ‘places where I have to scholarly’ and ‘places where I can phone it in’. (Not all researchers are like this, I’m talking about the ones who consider anything other than research beneath them.)

What a shame! What a terrible missed opportunity for both these people who should be more aware of the issues of learning and teaching, and for the students who could be learning so much more from them? But when you actually talk to these academics, some of them just don’t liked teaching, they don’t see the point of putting effort into it or (in some cases) they just don’t know what to do and how to improve so they hunker down and try to let it all slide around them.

Part of this is the selective memory that we have of ourselves as students. I’m lucky – I was terrible. I was fortunate enough to be aware and mature enough as I reconstructed myself as a good student to see the transformative process in action. A lot of my peers are happy to apply rules to students that they wouldn’t (or don’t ) apply to themselves now or in the past, such as:

“I’m an academic who doesn’t like teaching, despite being told that it’s part of my job, so I’ll do the minimum required – or less on some occasions. You, however, are a student who doesn’t like the sub-standard learning experiences that my indifference brings you but I’m telling you to do it, so just do it or I’ll fail you.”

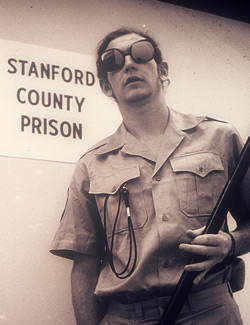

This isn’t just asymmetrical, this is bordering on the Stanford Prison Experiment, an arbitrary assignation of roles that leads to destructive power-derived behaviour. But, if course, if you don’t enjoy doing something then there are going to be issues.

Have we actually ever asked people these key questions as a general investigation? “Do you like teaching?” “What do you enjoy about teaching?” “What can we do to make you enjoy teaching more?” Would this muddy the water or clear the air? Would this earth our non-teaching teachers and fire them up?

Even where people run vanity courses (very small scale, research-focused courses design to cherry pick the good students) they are still often disappointed because, even where you can muster the passion to teach, if you don’t really understand how to teach or what you need to do to build a good learning experience, then you end up with these ‘good’ students in this ‘enjoyable’ course failing, complaining, dropping out and, in more analogous terms, kicking your puppy. You will now like teaching even less!

It’s blindingly obvious that some people don’t like teaching but, much as we wouldn’t stand out the front of a class and yell “PASS, IDIOTS!”, I’m looking for other good examples where we start to ask people why they don’t want to do it, what they’re worried about, why they don’t respect it and how we can get them more involved in the L&T community.

Let’s face it, when you love teaching, the worst day with the students is still a pretty good day. It would be nice to share this joy further.

In A Student’s Head – Mine From 26 Years Ago

Posted: August 11, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, ALTA, blogging, collaboration, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, feedback, games, higher education, in the student's head, principles of design, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking Leave a commentI attended an Australian Council of Deans of ICT Learning and Teaching Academy event run by Elena Sitnikova from the University of South Australia. Elena is one of the (my fellow?) Fellows in ALTA and works in Cyber Security and Forensic Computing. Today’s focus was on discussing the issues in ICT education in Australia, based on the many surveys that have been run, presenting some early work on learning and teaching grants and providing workshops on “Improving learning and teaching practice in ICT Education” and “Developing Teamwork that Works!”. The day was great (with lots of familiar faces presenting a range of interesting topics) and the first workshop was run by Sue Wright, graduate school in Education, University of Melbourne. This, as always, was a highly rewarding event because Sue forced me to go back and think about myself as a student.

This is a very powerful technique and I’m going to outline it here, for those who haven’t done it for a while. Drawing on Bordieu’s ideas on social and cultural capital, Sue asked us to list our non-financial social assets and disadvantages when we first came to University. This included things like:

- Access to resources

- Physical appearance

- Educational background

- Life experiences

- Intellect and orientation to study

- Group membership

- Accent

- Anything else!

When you think about yourself in this way, you suddenly have to think about not only what you had, but what you didn’t have. What helped you stay in class?What meant that you didn’t show up? From a personal perspective, I had good friends and a great tan but I had very little life experience, a very poor study ethic, no real sense of consequences and a very poor support network in an academic sense. It really brought home how lucky I was to have a group of friends that kept me coming to University. Of course, in those pre-on-line days, you had to come to Uni to see your friends, so that was a good reason to keep people on campus – it allowed for you to learn things by bumping into a people, which I like to refer to as “Brownian Communication”.

This exercise made me think about my transition to being a successful student. In my case, it took more than one degree and a great deal more life experience before I was ready to come back and actually succeed. To be honest, if you looked at my base degree, you’d never have thought that I would make it all the way to a PhD and, yet, here I am, on a path where I am making a solid and positive difference.

Sue then reminded people of Hofstede’s work on cultural dimensions – power distance, individualism versus collectivism, and uncertainty avoidance. How do students work – do they need a large ‘respect gap’ between student and teacher? Do they put family before their own study? Do they do anything rather than explore the uncertain? It’s always worth remembering that, where “the other” exists for us, we exist as “the other” reciprocally. While it’s comfortable as white, culturally English and English speaking people to assume that “the other” is transgressing with respect to our ‘dominant’ culture, we may be asking people to do something that is incredibly uncomfortable and goes far beyond learning another language.

One of the workshop participants was born and grew up in Korea and he made the observation that, when he was growing up, the teacher was held at the same level of the King and your father – and you don’t question the King or your father! He also noted that, on occasion, ‘respect’ had to be directed towards teachers that they did not actually respect. He had one bad teacher and, in that class, the students asked no questions and just let the teacher talk. As someone who works within a very small power distance relationship with y students, I have almost never felt disrespected by anything that my students do, unless they are actively trying to be rude and disrespectful. If I have nobody following, or asking questions, then I always start to wonder if I’ve been tuned out and they are listening to the music in their heads. (Or on their iPhones, as it is the 21st Century!)

Australia is a low power distance/high individualism culture with a focus on the short-term in many respects (as evidence by profit and loss quarterly focus and, to be frank, recent political developments). Bringing people from a high PD/high collectivism culture, such as some of those found in South East Asia, will need some sort of management to ensure that we don’t accidentally split the class. It’s not enough to just say “These students do X” because we know that we can, with the right approach, integrate our student body. But it does take work.

As always, working with Sue (you never just listen to Sue, she always gets you working) was a very rewarding and reflective activity. I spent 20 minutes trying to learn enough about a colleague from UniSA, Sang, that I could answer questions about his life. While I was doing this, he was trying to become Nick. What emerged from this was how amazingly similar we actually are – different Unis, different degrees, different focus, one Anglo-origin, one Korean-origin – and it took us quite a while to find things where we were really so different that we could talk about the challenges if we had to take on each other’s lives.

It was great to see most of the Fellows again but, looking around a large room that wasn’t full to the brim, it reminded me that we are often talking to those people who already believe that what we’re doing is the right thing. The people that really needed to be here were the people who weren’t in the room.

I’m still thinking about how we can continue our work to reach out and bring more people into this very, very rewarding community.

Declining Quality (In the Latin Sense)

Posted: August 10, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, community, education, educational problem, elitism, ethics, Generation Why, higher education, measurement, quality, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a comment“I’m quality. You’re a mediocrity. He’s rubbish.”

These are some of the (facetious) opening words from a recent opinion piece in The Australian by Professor Greg Craven, Vice Chancellor of Australian Catholic University. In this short piece, entitled (sic) “When elitism rules the real elite is lost in shuffle” (as, apparently, is the punctuation) he addresses that fundamental question “what is quality?” As he rightly points out, basing our assessment of quality of a student on an end-of-secondary-school mark (the Australian Tertiary Admission Rank, or ATAR, in Australia, or the equivalent in any other country) when it tells you nothing about knowledge, capacity or intellect.

What appears to be a ‘low’ ATAR of 66 tells you that this student performed better than two thirds of his or her peers in this young. In Craven’s own words:

“So moaning about an ATAR of 51 to 80 is like crying over an Olympic silver medal. No, it’s not gold, but you still swim faster than most people.”

There is no assessment of the road taken to reach the ATAR either. A student who overcame ferocious personal and societal disadvantage to earn a 70 would look exactly the same as a privileged and gifted student who put in a reasonable effort and achieved the same rank. From a University educator’s perspective, when the going gets tough, I’m pretty sure I know who is more likely to stay in the course and develop the right skill set. We see the ‘gifted but unfocused’ drift in, realise that actual work is required and then drift out again with monotonous regularity. The strugglers, the strivers, the ones who had to fight through to get here – that tenacity would be wonderful to measure.

The ATAR serves a useful purpose as a number that we can use to say “These students can come in” and “these can’t”, except that a number of factors affect the setting of that cut-off. The first is that high prestige courses lose that prestige if you drop the cut-off. Students from certain backgrounds will not select low ATAR courses, even if they are known to be of higher value or rigour, because they reverse shop on the cut-off score. The notion that being a single ATAR point short of getting in is anything other than noise is, obviously, not valid. It’s not as if we sat down and said that the ATAR corresponds to a certain combination of all of these desirable traits and being one short is just not good enough.

Craven makes a good point. The ATAR is a convenient tool but a meaningless number. Determining the genuine qualities of a student is not easy and working out which qualities map to the ‘ideal’ student who will perform well in the University setting is nigh-on impossible. True quality assessment is multi-faceted. It allow for bad years, slow starts or disadvantage, and alternative pathways. Education is opportunity – using quality as an argument to exclude people is a weapon that has been overused in the past and should be put down now. We seem to believe that hitting the government goal of 40% of the population entering higher education requires us to let in just about anyone and the sky will fall – low quality will ruin us! As Craven says, if the OECD can achieve 40%, why can’t we? Are we really all that special?

Craven makes two points that really resonate with me. Firstly, that it is the graduates that come out that determine the final quality. To be honest, if you want to see how good a University is, look at its graduates in about 20 years. You’ll know about the person and the institution by doing that. If the input quality of student is so important then what exactly is it that we are doing at the Uni level? Just minding them for three years while they… excel?

Secondly, that quality is not personal but national. To quote Craven again:

A country that discards its talent out of prejudice or poor policy fatally weakens its own productivity.

Determining the quality of a student but looking at one number, taken at a point where their personality has barely formed, which is not generous in its accommodation of struggle or disadvantage, is utterly the wrong way to express a complex concept such as quality.

What is quality? That’s the homework that Craven leaves us with – define “quality”. Really.

Teaching Ethics in a Difficult World: Free Range and Battery Games

Posted: August 9, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, blogging, community, education, educational problem, ethics, free range games, games, higher education, in the student's head, principles of design, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, time banking, work/life balance, workload 2 Comments(Note, this is not a post about the existing game company, Free Range Games, although their stuff looks cool!)

I enjoy treating ethics or, to be more precise, getting the students to realise the ethical framework that they all live within. I’ve blogged before about this and how easy it is to find examples of unethical behaviour but, as we hear more stories about certain ‘game-related’ industries and the way that they teach testers, it becomes more and more apparent that we are reaching a point where the ethical burden of a piece of software may end up becoming something that we have to consider.

We’re already aware of the use of child labour in some products and people can make a decision not to shop at certain stores or buy certain products – but this requires awareness and tying the act to the brand.

In the areas I live in, it’s very hard to find a non-free range chicken, even in a chicken take-away shop (for various definitions of ‘free range’ but we pretty much do mean ‘neither battery nor force fed’) and eggs are clearly labelled. Does this matter to you? If so, you can make an informed decision. Doesn’t matter to you? Buy the cheapest or the tastiest or whichever other metric you’re using.

But what about games? You don’t have to look far (ea_spouse and the many other accounts available) to see that the Quality Assurance roles, vital to good games, are seeing a resurgence in the type of labour management that is rapidly approaching the Upton Sinclair Asymptote. Sinclair wrote a famous turn-of-the 20th Century novelisation of the conditions in the meat packing industry, “The Jungle”, that, apart from a rather dour appeal to socialism at the end, is an amazing read. It changed conditions and workers’ rights because it made these invisible people visible. Once again, as well apparently fall in love with the ‘wealth creators’ (an Australian term that is rapidly become synonymous with ‘robber baron’) all over again, we are approaching this despite knowing what the conditions are.

What I mean by this is that it is well known that large numbers of staff in the QA area in games tolerate terrible conditions – no job security, poor working conditions, malicious and incompetent management – and for what? To bring you a game. It’s not as if they are fighting to maintain democracy (or attack democracy, depending on what you consider to be more important) or staying up for days on end trying to bring the zombie infection under control. No, the people who are being forced into sweatboxes, occasionally made to work until they wet themselves, who are unceremoniously fired at ‘celebration’ events, are working to make sure that the people who wrote your game didn’t leave any unexplained holes in the map. Or that, when you hit a troll with an axe, it inflicts damage rather than spontaneously causing the NyanCat video to play on your phone.

This discussion of ethics completely ignores the ethics of computer games that demean or objectify women, glorify violence or any of the ongoing issues. Search for ethics of video games and it is violence and sexism that dominates the results. It’s only when you start searching for “employee abuse video game” that you start to get hits. Here are some quotes from one of them.

It seems as though the developers of L. A. Noire might have been under more pressure themselves than any of the interrogated criminals in their highly praised crime drama. Reports have surfaced about employees being forced to work excruciating hours, in some cases reaching 120 hour weeks and 22 hour days. In addition, a list has been generated of some 130 members of the Australian-based Team Bondi, the creators of L. A. Noire, whose names have been omitted from the game’s own credits.

…

On the subject of the unprecedented scope of the project for Australian developers, McNamara replied, “The expectation is slightly weird here, that you can do this stuff without killing yourself; well, you can’t, whether it’s in London or New York or wherever; you’re competing against the best people in the world at what they do, and you just have to be prepared to do what you have to do to compete against those people. The expectation is slightly different.”

The saddest thing, to me, is that everyone knows this. The same people who complain on my FB feed back how overworked they are and how little they see their family then go out and buy games that have been produced in electronic sweatshops. You didn’t buy L. A. Noire? Rockstar San Diego are on the “overworking staff” list for “Red Dead Redemption” and the “not crediting everyone” for “Manhunt 2”. (That last one might not be so bad!)

Everyone talks about the crunch as if it’s unavoidable. Well, yes , it is, if you intend to work people to the crunch. We’ve seen similar argument for feedlot meat production, battery animals and, let’s not forget, that there have always been “excellent” reasons for slavery in economic and social terms.

This is one of the hardest things to talk about to my students because they’re not dumb. They read, often more widely than I do in these areas. They know that for all my discussions of time management and ethics, if they get a certain kind of job they will work 7 days a week, 10-14 hours a day, in terrible conditions and maybe, just maybe, if they sell their soul enough they can get a full-time job, rather than being laid off indiscriminately. They know that the message coming down from these companies is “maximum profit, minimum spend” and, of course, most of these game companies aren’t profitable so that’s less about being mercenary and more about survival.

But, given that these products are not exactly… essential (forgive me, Deus Ex!), one has to wonder whether terms like ‘survival’ have any place in this discussion. Is it worth nearly killing people, destroying their social lives and so one, to bring a game to market? People often say “Well, they have a choice” and, in some ways, I suppose they do – but in an economic market where any job is better than job, and people can make decisions at 15 that lead to outcomes they didn’t expect at 25, this seems both ungenerous and thoughtless.

Perhaps we need the equivalent of a ‘Free Range/Organic’ movement for games: All programmers and QA people were officially certified to have had at least 8 hours sleep a night, with a minimum break of 50 hours every 6 days and were kept at a maximum density of 2 programmers per 15 square metres, in a temperature and humidity controlled environment that meets recognised comfort standards.

(Yeah, I didn’t include management. I think they’re probably mostly looking after themselves on that one. 🙂 )

Then you can choose. If it matters to you, buy 21st century Labour Force Games – Ethically and sustainably produced. If it doesn’t matter, ignore it and game on.

Let’s stop subsidising education! (Andrew Norton, Grattan Institute)

Posted: August 7, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: blogging, education, educational problem, ethics, higher education 4 CommentsThis article was published in the Australian, Australia’s national (and conservatively inclined) newspaper. This is the lead quote:

“Tuition subsidies merely redistribute income to students and graduates. The general public, particularly those who do not go to university, are worse off. They forgo other government benefits or pay higher taxes while receiving nothing additional in return,” Andrew Norton.

This quote comes from a report from the Grattan Institute, written by Andrew Norton, entitled “Graduate Winners”. His thesis is that, counter-intuitively, subsidising education doesn’t level the playing field, rather it robs non-University educated Australians of their fair share.

Basically, Australia runs a deferred payment scheme that is also government subsidised. Norton’s point is, effectively, that having put everything into a loan scheme, the amount doesn’t matter and it therefore wouldn’t disadvantage people to pay more. We’ve seen this before, of course, where people remove subsidies and let the market fix a price: as the article says, in New Zealand this led to a tripling and Britain is in the middle of major hikes. We’ve also seen the US where students never get out from under their debt load.

Here, in Australia, people do actually clear their debt. Not quickly, admittedly, but it’s possible. You can get out and clear of your debt under the current scheme. It’s relatively embarrassing for Norton that he wasn’t (apparently) present at HERDSA when speakers talked about the socially disadvantaged being more acutely debt averse than other sectors – and increasing the debt is not going to help that problem.

I must be honest, I always have a suspicion of schemes that, from whatever basis of argument, seem to end up with ‘the rich kids get places’, but this is a personal bias. Perhaps this report contains the convincing argument that will sway me, finally? (To be honest, the whole document has this weird aroma of capitalism wrapped up in a central planning framework, running on the sniff of the invisible hand.)

What I find fascinating is that, in the middle of an Australian federal sector that is increasingly focussing on the wealth creators, there appears to be no connection between the Universities and their contribution to a society, the report is focused on personal salaries and assumes that everyone goes out to maximise their income. The section of the report that discussed public benefits talks about increased tax benefit, tolerance and things like that – but what seems to be missing (I did read it at speed so that might be fault) is a discussion of the benefit of having well-trained professionals in your society.

It’s as if the students of Universities have never turned into the professionals that have done small things like design our roads, keep our air fleets running, stop disease from killing the population – you know, little things. Is it seriously contended that the people who have graduated from University have never done anything at all except take extra salary at the expense of other people?

I won’t say any more on this as I need to digest it in more detail but I thought you might be interested in a completely different view on how to handle a public educational system.

Silk Purses and Pig’s Ears

Posted: August 6, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, community, curriculum, design, education, educational problem, educational research, ethics, feedback, grand challenge, higher education, in the student's head, learning, principles of design, resources, student perspective, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, winemaking 2 CommentsThere’s an old saying “You can’t make a silk purse out of a pig’s (or sow’s) ear”. It’s the old chestnut that you can’t make something good out of something bad and, when you’re talking about bad grapes or rotten wood, then it has some validity (but even then, not much, as I’ll note later). When it’s applied to people, for any of a large range of reasons, it tends to become an excuse to give up on people or a reason why a lack of success on somebody’s part cannot be traced back to you.

I’m doing a lot of reading in the medical and general ethics as part of my preparation for one of the Grand Challenge lectures. The usual names and experiments show up, of course, when you start looking at questionable or non-existent ethics: Milgram, the Nazis, Stanford Prison Experiment, Unit 731, Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, Little Albert and David Reimer. What starts to come through from this study is that, in many of these cases, the people being experimented upon have reached a point in the experimenter’s eyes where they are not people, but merely ‘subjects’ – and all too often in the feudal sense as serfs, without rights or ability to challenge what is happening.

But even where the intention is, ostensibly, therapeutic, there is always the question of who is at fault when a therapeutic procedure fails to succeed. In the case of surgical malpractice or negligence, the cause is clear – the surgeon or a member of her or his team at some point made a poor decision or acted incorrectly and thus the fault lies with them. I have been reading up on early psychiatric techniques, as these are full of stories of questionable approaches that have been later discredited, and it is interesting in how easy it is for some practitioners to wash their hands of their subject because they had a lack of “good previous personality” – you can’t make a silk purse out of a pig’s ear. In many cases, with this damning judgement, people with psychiatric problems would often be shunted off to the wards of mental hospitals.

I refer, in this case, to William Sargant (1907-1988), a British psychiatrist who had an ‘evangelical zeal’ for psychosurgery, deep sleep treatment, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and insulin shock therapy. Sargant used narcosis extensively, drug induced deep sleep, as he could then carry out a range of procedures on the semi- and unconscious patients that they would have possibly learned to dread if they have received them while conscious. Sargant believed that anyone with psychological problems should be treated early and intensively with all available methods and, where possible, all these methods should be combined and applied as necessary. I am not a psychiatrist and I leave it to the psychiatric and psychotherapy community to assess the efficacy and suitability of Sargant’s methods (they disavow them, for the most part, for what it’s worth) but I mention him here because he did not regard failures as being his fault. It is his words that I am quoting in the previous paragraph. People for whom his radical, often discredited, zealous and occasionally lethal experimentation did not work were their own problem because they lacked a “good previous personality”. You cannot, as he was often quoted to have said, make a silk purse out of a pig’s ear.

How often I have heard similar ideas being expressed within the halls of academia and the corridors of schools. How easy a thing it is to say. Well, one might say, we’ve done all that we can with this particular pupil, but… They’re just not very bright. They daydream in class rather than filling out their worksheets. They sleep at their desks. They never do the reading. They show up too late. They won’t hang around after class. They ask too many questions. They don’t ask enough questions. They won’t use a pencil. They only use a pencil. They talk back. They don’t talk. They think they’re so special. Their kind never amounts to anything. They’re just like their parents. They’re just like the rest of them.

“We’ve done all we can but you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.”

As always, we can look at each and every one of those problems and ask “Why?” and, maybe, we’ll get an answer that we can do something about. I realise that resources and time are both scarce commodities but, even if we can’t offer these students the pastoral care that they need (and most of those issues listed above are more likely to be social/behavioural than academic anyway), let us stop pretending that we can walk away, blameless, as Sargant did because these students are fundamentally unsalvageable.

Yeah, sorry, I know that I go on about this but it’s really important to keep on hammering away at this point, every time that I see how my own students could be exposed to it. They need to know that the man that they’re working with expects them to do things but that he understands how much of his job is turning complex things into knowledge forms that they can work with – even if all he does is start the process and then he hands it to them to finish.

Do you want to know how to make great wine? Start with really, really good grapes and then don’t mess it up. Want to know how to make good wine? Well, as someone who used to be a reasonable wine maker, you can give me just about anything – good fruit, ok fruit, bad fruit, mouldy fruit – and I could turn it into wine that you would happily drink. I hasten to point out that I worked for good wineries and the vast quantity of what I did was making good wine from good grapes, but there were always the moments where you had something that, from someone else’s lack of care or inattention, had got into a difficult spot. Understanding the chemical processes, the nature of wine and working out how we could recover the wine? That is a challenge. It’s time consuming, it takes effort, it takes a great deal of scholarly knowledge and you have to try things to see if they work.

In the case of wine, while I could produce perfectly reasonable wine from bad grapes, simple chemistry prevents me from leaving in enough of the components that could make a wine great. That is because wine recovery is all about taking bad things out. I see our challenge in education as very different. When we find someone who is need of our help, it is what we can put in that changes them. Because we are adding, mentoring, assisting and developing, we are not under the same restrictions as we are with wine – starting from anywhere, I should be able to help someone to become a great someone.

The pig’s ears are safe because I think that we can make silk purses out of just about anything that we set our minds to.