The Student of 2040

Posted: April 10, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, educational problem, higher education, learning, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches 1 CommentOn occasion, I wonder about where students and teachers will be towards the end of my teaching career. Let us be optimistic and say that I’ll still be teaching in 2040 – what will my students look like? (I’m not sure that teaching at that age is considered optimistic but bear with me!)

Right now we’re having to adapt to students who can sit in lectures and, easily and without any effort, look things up on wireless or 3G connections to the Internet – searching taking the role of remembering. Of course, this isn’t (and shouldn’t be) a problem because we’re far more than recitation and memorisation factories. There are many things that Wikipedia can’t do. (Contrary to what at least a few of my students believe!)

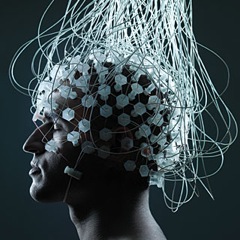

But what of the future? What of implanted connections that can map entire processes and skills into the brain? What of video overlays that are invisibly laid over the eye? Very little of what we use today to drive thinking, retrieval, model formation and testing will survive this kind of access.

It would be tempting to think that constant access to the data caucus would remove the need for education but, of course, it only gives you answers to questions that have already been asked and answers that have already been given – a lot of what we do is designed to encourage students to ask questions in new areas and find new answers, including questioning old ones. Much like the smooth page of Wikipedia gives the illusion of a singularity of intent over a sea of chaos and argument, the presence of many answers gives the illusion of no un-answered questions. The constant integration of information into the brain will no more remove the need for education than a library, or the Internet, has already done. In fact, it allows us to focus more on the important matters because it’s easier to see what it is that we actually need to do.

And so, we come back to the fundamentals of our profession – giving students a reason to listen to us, something valuable when they do listen and a strong connection between teaching and the professional world. If I am still teaching by the time I’m in my 70s then I can only hope that I’ve worked out how to do this.

Grand Challenges in Education – When we say grand, we mean GRAND!

Posted: March 31, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, educational problem, grand challenge, higher education, reflection, teaching, teaching approaches, tools 2 CommentsSome time ago, Mark Guzdial posted on the Grand Challenges in the US National Educational Technology Plan. If I may summarise the four, huge, challenges, they were:

- A real-time, self-optimising difficulty-adjusting, interactive learning experience delivery system.

- A similarly high-end system for assessment of cross-discipline complex aspects of expertise and competencies.

- Integrated capture, aggregation, mining and sharing of content, learning and financial data across all platforms in near real-time.

- Identify the most effective principles of online learning systems and on/offline systems that produce equal or better results than conventional instruction in half the time and half the cost.

Wow. That’s one heck of a list. Compare that with the list of grand challenges from the March, 2011, report of National Science Foundation Advisory Committee for Cyberinfrastructure Task Force on Grand Challenges, which defines the grand challenge problems for my discipline, Computer (Cyber) Science and Engineering. By looking at some very complex problems, they arrived at the following list of areas in which great strides can, and should, be made:

- Advanced Computational Methods and Algorithms

- High Performance Computing

- Software Infrastructure

- Data and Visualisation

- Education, Training and Workforce Development

- Grand Challenge Communities.

Let me rewrite this last list in simpler, discipline free, terms:

- Better methods for solving hard problems.

- Big machines for solving hard problems.

- Good systems to run on the big machines, to support the better methods.

- Ways to see what results we have – people can see the results to make better decisions.

- Training people to make steps 1-4 work.

- Bring people together to make 1-5 work better with greater efficiency.

Now, lets look back at the four USNETP educational grand challenges to see if we can as easily form such a cohesive flow – we want to be able to see how it all works together.

- Smart learning systems.

- Smart assessment systems.

- Data and Visualisation. (Nick note: get into data and visualisation! 🙂 )

- Fusing the best of the old and the best of the new.

Now, the USNETP focus is on useful R&D and these challenges are part of their overall view of “they all combine to form the ultimate grand challenge problem in education: establishing an integrated, end-to-end real-time system for managing learning outcomes and costs across our entire education system at all levels. ” but what immediately leaps out at me are the steps 5 and 6 from the previous list. Rather than embed the training and community aspects somewhere in the rest of a document, why not embrace this at the same level if we’re talking about grand challenges in Education? That would give us:

- Training educators to make steps 1-4 work.

- Forming communities of practice to make 1-5 work better with greater efficiency.

Now these last two steps, of course, are what we’re doing with the conferences, the journals, the meetings and blogs like this but it makes a lot of sense when we see it inside my discipline, so it seems to make sense in the general field of education. There’s no doubt that these two last steps are easily as hard to manage at scale as the other projects, even interoperating with them. In fact, by making them huge challenges we increase their worth, justify effort and validate the research community built up around them. These are financially-sensitive times, where academics have to provide a value for their work. Allocating these important tasks to the grand challenge level recognises the difficulty, the uncertainty of being able to solve the problem and the sheer amount of work that may be involved.

These are, of course, only my thoughts and I have a great deal to learn in this space. I’m still searching for answers but if there’s a nice convenient report that says “Well, duh, Nick, we’re doing that right here, right now” I look forward to correction and enlightenment.

But, if it’s not already part of the USNETP grand challenges – what do you think? Should it be?

Fixing Misdirected Effort: Guiding, with the occasional shove.

Posted: March 19, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, educational problem, frankenstein, higher education, resources, teaching, teaching approaches Leave a commentMy students have a lot of questions and my job is often as much about helping them find the right questions as it is about finding the answers. One of the most frustrating aspects of education is when people fixate on the wrong thing, or invest their effort into the wrong ventures. I talked before how I believed that far more students were procrastinators versus lazy, they invest their effort without thinking about the time that they need or all of the responsibilities that they have.

That’s why it gets frustrating when all of the effort that they can expend goes into the wrong pathway. I’ll give you a couple of examples. We run a forum where students receive e-mail notification and, because the forum is an official dissemination point, students are compulsorily enrolled into certain forums and will receive mail whenever discussion takes place. Every year, there’s at least one student who starts complaining about receiving ‘all this e-mail’. (Generally not more than 10 messages a week, except during busy times when it might rise to 20-30. Per week.) We then reply with the reasons we’re doing it. They argue. Of course, the e-mail load of the forum then does rise, because of the mailed complaints about the e-mail load – not to mention the investment of time. The student who complains that mail is wasting their time generally spends more time in that one exchange than processing the mail for the semester would have cost.

Another example is students trying to work out how much effort they can avoid in writing practical submissions. They’ll wait outside your office for an hour and talk for hours (if you let them) about whether they have to do this bit, or if they can take this shortcut, and what happens if I do that. Sitting down and trying it will take about 5 minutes but, because they’re fearful or haven’t fully understand how they can improve, they spend their time trying to dodge work and, anecdotally, it looks like some of these people invest more time in trying to avoid the work than actually doing the work would have required. This is, of course, ignoring the benefits of doing the work in terms of reinforcement and learning.

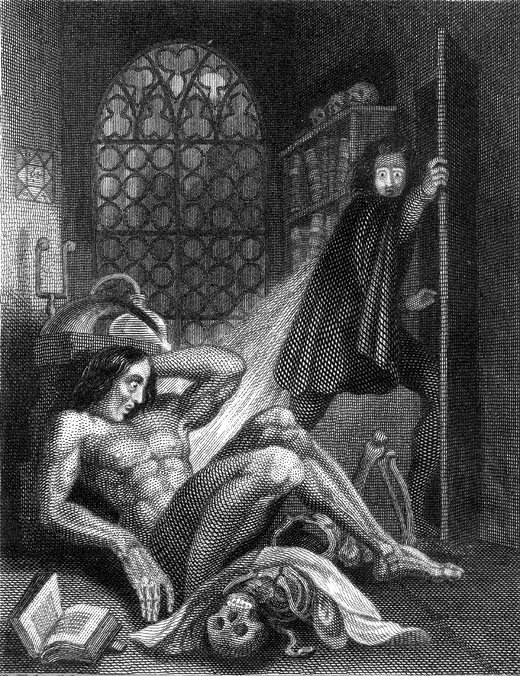

Then, of course, we have the curse of the Computer Science academic, that terror to the human eye – the plagiarised, patchwork monstrosity of Frankencode!

Frankencoding, my term for the practice of trying to build software by Googling sections (I’m a classicist, or I’d call it Googlecoding) and jamming them together, is a major time waster here as well. If you design your software and built it up, you understand each piece and can debug it to get it working. If you surf news groups and chuck together bits and pieces that you don’t understand, your monster will rise up and lurch off to the village trailing disaster in its wake. Oh, and for the record, it’s really obvious to a marker when it has happened and even more obvious when we ask you WHY you did something – if you don’t know, you probably didn’t write it and “I got it off the Internet” attracts nothing good in the way of marks.

What I want to do is get effort focused on the right things. I know that my students regard most of their studies as a mild inconvenience, so I don’t want them spending what time they do devote to academia on the wrong things. This means that I have to try and direct discussions into useful pathways, handle the ‘what if I do this’ by saying ‘why don’t you go and try it. It’ll take 5 minutes’ (framed correctly) and by regularly checking for plagiarised code – including tests of understanding that accompany practical coding exercises such as test reports and design documents. Once again, understanding is paramount and wasted effort is not useful to anyone.

I like to think of it a gentle guidance in the right direction. With the occasional friendly, but firmer, shove when someone looks like they’re going seriously off the rails. After all, we have the same goals: none of us want to waste our time!

SIGCSE Oh, oh, oh, it’s magic!

Posted: March 3, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: design, education, educational problem, fiero, higher education, magic, puzzles, reflection, sigcse, teaching, teaching approaches, tools Leave a commentIf you’re at SIGCSE, then you’re probably one of the 1,000,000 people who jammed into the pretty amazing Wednesday session, Demystifying Computing with Magic, with Dan Garcia and David Ginat. Dan and David coped very well with a room that seemed to hold more and more people – in keeping with a magic show, we were all apparently trapped in a magic box.

The key ideas behind this session was that Dan and David would show us five tricks that would teach or introduce important computing notions, such as discrete maths, problem representation, algorithmic patterns and, the catch-all, general notions. Drawing on Silver’s 1997 paper, Fostering Creativity Through Instruction Rich In Mathematical Problem Solving and Problem Posing (It’s better in German, trust me), they focused on the notions of fluence (diverse directions for exploration), flexibility (adaptation to the task at hand – synonymous with cognitive flexibility), originality (unfamiliar utilisation of familiar notation), and awareness (being aware of the possible fixations[?] – to be honest, I didn’t quite get this and am still looking at this concept).

The tricks themselves were all fun and had a strong basis in the classical conceit of the stage magician that everything is as it seems, while being underpinned by a rigorous computational framework that explained the trick but in a way that inspired the Gardernesque a-ha! One trick guaranteed that three people could, without knowing the colour of their own hats, be able to guess their own hat colour, based on observing the two other hats, and it would be guaranteed that at least one person would get it right. There were card tricks – showing the important of encoding and the importance of preparation – modular arithmetic, algorithms, correctness proofs and, amusingly, error handling.

Overall, a great session, as evidenced by the level of participation and the number of people stacked three-high by the door. I had so many people sitting near my feet I began to wonder if I’d started a cult.

The final trick, Fitch Cheney’s Five Card Trick was very well done and my only minor irritation is that we were planning to use it in our Puzzle Based Learning workshop on Saturday – but if it’s going to be done by someone else, then all you can ask is that they do it well and it was performed well and explained very clearly. It even had 8 A-Ha’s! That’s enough to produce 2.66 Norwegian pop bands! If you have a chance to see this session anywhere else, I strongly recommend it.

(A useful website, http://www.cs4fn.org/magic, was mentioned at the end, with lots of resources and explanation for those of you looking to insert a little mathemagic into your teaching.)

If you’re going to put the disadvantaged into a box, why not just nail it shut?

Posted: February 16, 2012 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: education, educational problem, higher education, reflection, teaching 2 CommentsI’m currently attending a set of talks on preparedness for teaching first-year mathematics (if you’re at IISME, hi!) and the ‘pre’ talk was by Professor Celia Hoyles, from the UK, talking about her experiences in trying to get mathematics out of the doldrums in the UK.

Three things struck me about her talk.

- She had put a vast amount of effort into local and national initiatives, but there was no certainty in the future funding because of budget cuts.

- Too many students were exposed to mathematically-underqualified teachers. These teachers did not have sufficient mathematical training to actually be mathematicians and, in many cases, had no higher mathematics at all yet were teaching into that space.

- Even where funding was put into developing teachers, professional development was the first thing to be cut and the government-supplied teacher training scholarships, originally paid at a flat rate, was being awarded based on performance in the teaching degree.

The first fact is demoralising but it is the world we live in.

The second is terrible, because the vast majority of students in disadvantaged areas would never see a mathematics specialist, or someone who had seen any mathematics at all beyond that which they learned at 16 – certainly not at University.

The third fact caps it all off by saying that programs are doomed to be cut unless people put a priority on these programs! The kicker in the statement about training scholarships is that student teachers who completed a teaching and mathematics program at university would receive 20,000 pounds for a 1st Class degree, 15K for 2:1, 9K for 2:1 and nothing for a 3rd class degree. Now, for those unfamiliar with the UK system, 3rd class is not just a pass – it’s a little (not much) more than a pass. So you have passed your exams but we will pay you nothing for it. If that’s what you were depending upon – tough. Go and do something else. Even though you passed.

Would a University qualified mathematics teacher, whatever the degree, be more likely to have better mathematical knowledge than someone who didn’t study it all the way to the end of school? If the answer isn’t ‘yes’, then some serious introspection is required at certain higher educational institutions!

Fact 1 leads to Fact 3 – budget cuts lead to reduced expenditure and the most likely way to do that is to allocate money so that a reduced bucket goes to the ‘more deserving’. This is a tragedy in the context of Fact 2, because Fact 3 now means that a number of perfectly reasonable teachers may end up having to leave their degree because their funding dries up. Which means that the money expended is now wasted. So Fact 1 gets worse and Fact 2 gets worse.

Professor Hoyles started her talk by stating that her fundamental principle was that every student who wanted to study mathematics should be able to study mathematics, but 1, 2 and 3 conspire against this and restrict knowledge in a way that create a pit from which very few students will crawl out.

She mentioned a couple of reports, in outline, that I refer to here:

I ric, you ric, we all ric for… rubric?

Posted: January 31, 2012 Filed under: Education | Tags: education, educational problem, higher education, teaching, teaching approaches 1 CommentIn teaching, we use rubrics to let students know what our expectations of quality are. I can set an assignment, list my expectations in order to achieve a certain grade and, better still, I can then mark against the same statements. Clear, fair, transparent. Here’s an example for, say, an essay on developments in distributed systems in the early 21st Century. I don’t have access to some of my previous rubrics at the moment so this is a little ‘off the top of my head’. Please focus on the intent (conveying a specific requirement to the student) rather than and/or arrangement of clauses.

References:

- An unsatisfactory grade will be awarded for references if you have fewer than 5 relevant references or the references are not primary sources or high quality peer-reviewed publications. You should not include unreviewed work, Wikipedia entries (unless to illustrate a specific technical point that deals with Wikipedia or Wikipedia policy) or Personal Communications (unless you clear these with me first). To determine the ‘ranking’ or ‘quality’ of a publication, you may use Impact Factors or CORE/ERA rankings. If in doubt as to the nature of the publications or the quality of your references, check your references with me by posting to the main forum’s Student Questions section.

- To achieve a satisfactory mark, you must provide clear and accurate citations, at least 5 as described above, for all external material included in your work (see (web page reference) for University citation standards and avoiding accidental plagiarism).

- To achieve a mark in the range of credit or distinction, your clear and accurate citations should include at least 10 relevant references from A or A* journals and conferences.

- To achieve the best mark, your references should also reflect a thorough reading of the area, with at least 20 relevant references, 10 derived from A* journals and the remainder A/A* publications.

It’s fairly easy for a student to work out what they need to do in order to pass, do better and excel. It’s also fairly easy for me to mark because I know where the core reference should be coming from and, if one appears out of left field, then the worst case situation is that I learn about a new venue.

I would usually arrange this in tabular fashion so that all of the requirements for the essay were arranged along the left column and, as you moved across the row, you could look up to column top and see Unsatisfactory, Satisfactory and look in the intersection of row and column to find out what you have to achieve in aspect X to achieve outcome Y. There is still a great deal of room for movement in marking this but, as a framework, I find it useful.

Let me compare this with something I received once for an assignment.

References: Your references should be good, with enough to support your argument. Remember to cite correctly. We take plagiarism very seriously.

I leave it to the reader to decide which of these tell them what they have to do in a more useful way, and which they think would probably be easier to mark in a fair and consistent manner.

THE (Thinking Higher Education).

Posted: January 5, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: education, educational problem, higher education, MIKE, SWEDE 2 CommentsWell, if you’ve survived the MIKE post and the SWEDE post, you’ve probably guessed that I like acronyms. However, TMASTB (Too Many Acronyms Spoil The Broth), so I’ll present one more and go back to discussing other issues. However, these three acronyms together will drive a lot of what I talk about and, with any luck, I’ll have strangers around the world muttering “MIKE THE SWEDE” at each other.

I’m not holding my breath.

There are so many different ways to educate, some many different environments, students and teachers, choosing an approach that will work can sometimes appear to be an overwhelmingly difficult problem. How do I cater for everyone? How do I deal with large ranges in ability? How can I be fair to all the groups I deal with and, at the same, fair to myself and my own family, giving myself enough time to work and live.

This is where “THE” comes in. I’m not trying to solve every educational problem, I’m thinking about higher education. The students that I deal with have already shown that they can handle education to some extent, whether traditional classroom-based study, collaborative group learning in more experimental frameworks or home-schooling. They have passed sufficient entry requirements to attend classes at my institution. They can read. They can write. They are fundamentally numerate. They may have pre-requisite subject requirements to meet on top of this. For example, all of my students have at least one course of mathematics to the matriculation level. As an educator, I have so much to be grateful for in that a lot of the hard work has already been done by the educators before me, who excited these students about learning, who gave them the basis upon which they could develop to the point that they made it to me. For the families who supported them, or the groups that supported the students or the families when they families couldn’t do it by themselves.

I looked into publishing a book once, on computerising wineries (previous career), and I attended a really interesting workshop on pitching books to publishers. One of the most important pieces of advice was that no book was ever really suitable for ‘all ages from 8 to 80’, so don’t claim it. Work out who your book is for, write it for that group and then advertise it correctly. Who should my courses be suitable for? What do they come in with? What do I want them to leave with? How do I tell people that they will benefit from this course so come and try it?

Thinking Higher Education means thinking about students who have already demonstrated an ability to work within our systems, who have already stuck at education for 12+ years and who most likely perfectly capable of passing our courses, if we keep them engaged, do our jobs properly and their own lives don’t get in the way. Yes, there will be ranges of ability and dedication, but these tend to be smaller than are seen in the early primary or early secondary years. The kids who caused lots of trouble in class probably aren’t here anymore although, with any luck, they’ll sort themselves out in a while and we’ll welcome them back as mature-aged students with open arms. Yes, you’ll have mature-aged students sitting next to 17 year olds and you’ll need to think about that but if they’re sitting in your course then they need (and sometimes even want) you to teach them. Or to give them the right environment in which they can teach themselves. But they all need the same thing and, theoretically, they are on a much tighter track in their quest for degree completion than trying to match the diverse requirements of a group of 15 year olds sitting in an English class.

It’s not impossible. It’s certainly not easy and it doesn’t downgrade the role of a University educator but, despite having students from all over the world, the country, the age groups, the demographic spectrum – we can manage this problem and share our knowledge.

So THE is a positive thing, a reminder that our job is manageable, an appreciation of the work that has been carried out before by our colleagues in schools, a mark of respect to their successes and an awareness that students come to us with a great deal of potential and previous experience, both of which will shape their future.

Putting it together – Measurement, Environmental Awareness and Managing Scale, you get MIKE THE SWEDE.

Happy muttering!

(No more new acronyms for at least a few days, I promise!)