A Year of Beauty

Posted: January 1, 2016 Filed under: Education, Opinion | Tags: advocacy, authenticity, beauty, blogging, design, education, educational problem, educational research, good, higher education, plato, principles of design, reflection, socrates, teaching, teaching approaches, thinking, truth, vygotsky, workload 5 Comments

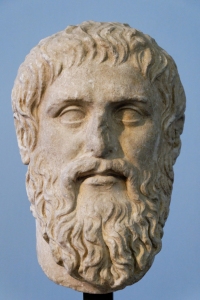

Plato: Unifying key cosmic values of Greek culture to a useful conceptual trinity.

Ever since education became something we discussed, teachers and learners alike have had strong opinions regarding the quality of education and how it can be improved. What is surprising, as you look at these discussions over time, is how often we seem to come back to the same ideas. We read Dewey and we hear echoes of Rousseau. So many echoes and so much careful thought, found as we built new modern frames with Vygotsky, Piaget, Montessori, Papert and so many more. But little of this should really be a surprise because we can go back to the writings of Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (Quinitilian) and his twelve books of The Orator’s Education and we find discussion of small class sizes, constructive student-focused discussions, and that more people were capable of thought and far-reaching intellectual pursuits than was popularly believed.

“… as birds are born for flying, horses for speed, beasts of prey for ferocity, so are [humans] for mental activity and resourcefulness.” Quintilian, Book I, page 65.

I used to say that it was stunning how contemporary education seems to be slow in moving in directions first suggested by Dewey a hundred years ago, then I discovered that Rousseau had said it 150 years before that. Now I find that Quntilian wrote things such as this nearly 2,000 years ago. And Marcus Aurelius, among other stoics, made much of approaches to thinking that, somehow, were put to one side as we industrialised education much as we had industrialised everything else.

This year I have accepted that we have had 2,000 years of thinking (and as much evidence when we are bold enough to experiment) and yet we just have not seen enough change. Dewey’s critique of the University is still valid. Rousseau’s lament on attaining true mastery of knowledge stands. Quintilian’s distrust of mere imitation would not be quieted when looking at much of repetitive modern examination practice.

What stops us from changing? We have more than enough evidence of discussion and thought, from some of the greatest philosophers we have seen. When we start looking at education, in varying forms, we wander across Plato, Hypatia, Hegel, Kant, Nietzsche, in addition to all of those I have already mentioned. But evidence, as it stands, does not appear to be enough, especially in the face of personal perception of achievement, contribution and outcomes, whether supported by facts or not.

Evidence of uncertainty is not enough. Evidence of the lack of efficacy of techniques, now that we can and do measure them, is not enough. Evidence that students fail who then, under other tutors or approaches, mysteriously flourish elsewhere, is not enough.

Authority, by itself, is not enough. We can be told to do more or to do things differently but the research we have suggests that an externally applied control mechanism just doesn’t work very well for areas where thinking is required. And thinking is, most definitely, required for education.

I have already commented elsewhere on Mark Guzdial’s post that attracted so much attention and, yet, all he was saying was what we have seen repeated throughout history and is now supported in this ‘gilt age’ of measurement of efficacy. It still took local authority to stop people piling onto him (even under the rather shabby cloak of ‘scientific enquiry’ that masks so much negative activity). Mark is repeating the words of educators throughout the ages who have stepped back and asked “Is what we are doing the best thing we could be doing?” It is human to say “But, if I know that this is the evidence, why am I acting as if it were not true?” But it is quite clear that this is still challenging and, amazingly, heretical to an extent, despite these (apparently controversial) ideas pre-dating most of what we know as the trappings and establishments of education. Here is our evidence that evidence is not enough. This experience is the authority that, while authority can halt a debate, authority cannot force people to alter such a deeply complex and cognitive practice in a useful manner. Nobody is necessarily agreeing with Mark, they’re just no longer arguing. That’s not helpful.

So, where to from here?

We should not throw out everything old simply because it is old, as that is meaningless without evidence to do so and it is wrong as autocratically rejecting everything new because it is new.

The challenge is to find a way of explaining how things could change without forcing conflict between evidence and personal experience and without having to resort to an argument by authority, whether moral or experiential. And this is a massive challenge.

This year, I looked back to find other ways forward. I looked back to the three values of Ancient Greece, brought together as a trinity through Socrates and Plato.

These three values are: beauty, goodness and truth. Here, truth means seeing things as they are (non-concealment). Goodness denotes the excellence of something and often refers to a purpose of meaning for existence, in the sense of a good life. Beauty? Beauty is an aesthetic delight; pleasing to those senses that value certain criteria. It does not merely mean pretty, as we can have many ways that something is aesthetically pleasing. For Dewey, equality of access was an essential criterion of education; education could only be beautiful to Dewey if it was free and easily available. For Plato, the revelation of knowledge was good and beauty could arose a love for this knowledge that would lead to such a good. By revealing good, reality, to our selves and our world, we are ultimately seeking truth: seeing the world as it really is.

In the Platonic ideal, a beautiful education leads us to fall in love with learning and gives us momentum to strive for good, which will lead us to truth. Is there any better expression of what we all would really want to see in our classrooms?

I can speak of efficiencies of education, of retention rates and average grades. Or I can ask you if something is beautiful. We may not all agree on details of constructivist theory but if we can discuss those characteristics that we can maximise to lead towards a beautiful outcome, aesthetics, perhaps we can understand where we differ and, even more optimistically, move towards agreement. Towards beautiful educational practice. Towards a system and methodology that makes our students as excited about learning as we are about teaching. Let me illustrate.

A teacher stands in front of a class, delivering the same lecture that has been delivered for the last ten years. From the same book. The classroom is half-empty. There’s an assignment due tomorrow morning. Same assignment as the last three years. The teacher knows roughly how many people will ask for an extension an hour beforehand, how many will hand up and how many will cheat.

I can talk about evidence, about pedagogy, about political and class theory, about all forms of authority, or I can ask you, in the privacy of your head, to think about these questions.

- Is this beautiful? Which of the aesthetics of education are really being satisfied here?

- Is it good? Is this going to lead to the outcomes that you want for all of the students in the class?

- Is it true? Is this really the way that your students will be applying this knowledge, developing it, exploring it and taking it further, to hand on to other people?

- And now, having thought about yourself, what do you think your students would say? Would they think this was beautiful, once you explained what you meant?

Over the coming year, I will be writing a lot more on this. I know that this idea is not unique (Dewey wrote on this, to an extent, and, more recently, several books in the dramatic arts have taken up the case of beauty and education) but it is one that we do not often address in science and engineering.

My challenge, for 2016, is to try to provide a year of beautiful education. Succeed or fail, I will document it here.

Beautiful! Looking forward to your writings as usual. Some reading recommendations along the way would be nice too.

LikeLike

Thanks for your post Nick – I really enjoyed reading it. Have you read Gert Biesta ‘The beautiful risk of education?’ (2014) I think you would find resonances in there.

LikeLike

Thanks Nick. I enjoyed reading your post. Have you read Gert Biesta (2014) The Beautiful Risk of Education. I think you would find resonances in there.

LikeLike

I’m looking forward to reading it! Thank you!

LikeLike

[…] Source: A Year of Beauty | Nick Falkner […]

LikeLike